As the Research Director of CURE, Jesse Keenan leads many of the center’s projects, drawing on his diverse professional and academic background in law, sustainable development, and housing policy to shape a bold intellectual project for CURE’s research. Keenan talked with Volume’s Jeffrey Inaba and Benedict Clouette about the need for an ethical foundation in the practice of real estate development, and the role of disciplinary knowledge in informing the decisions of professionals.

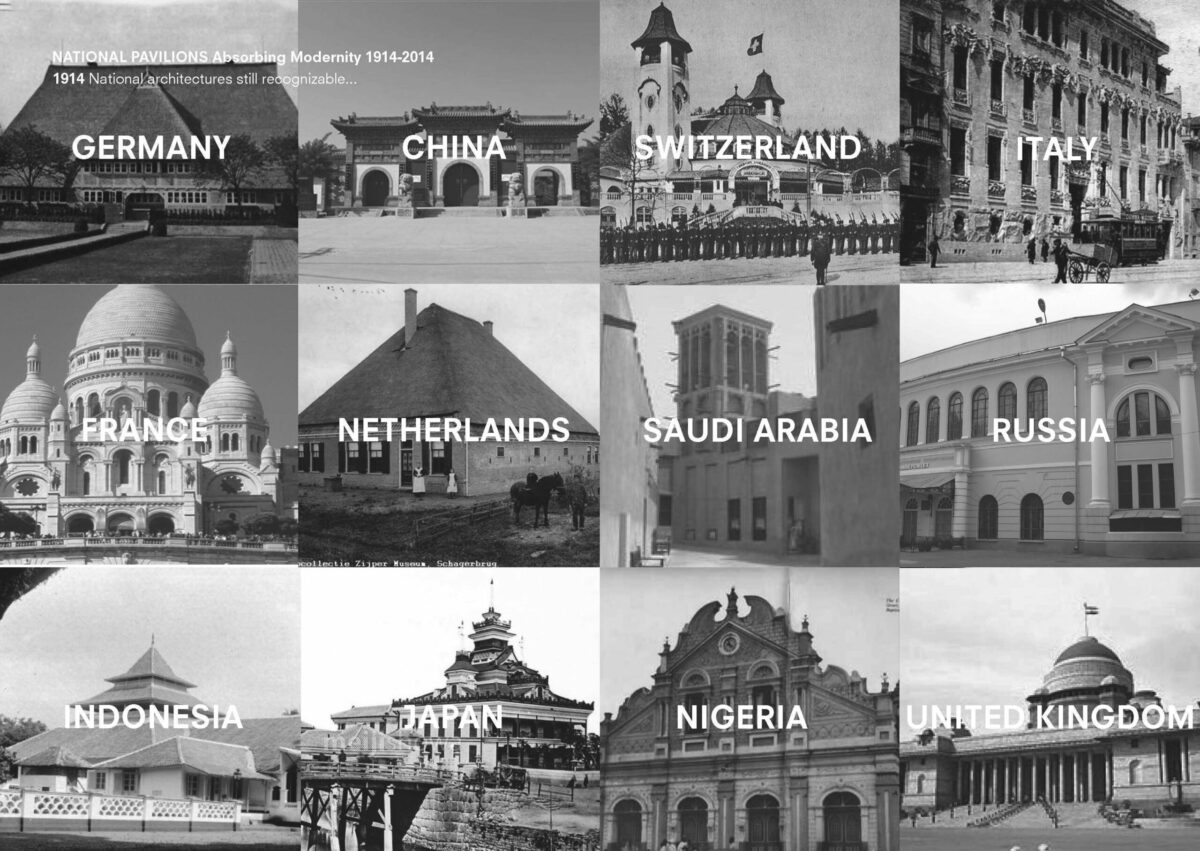

Hong Kong and Macau aren’t independent nations, yet they appear at the Biennale regardless. As recent appendages to China, they are undergoing an often-uncomfortable transition to a new political reality. Thomas Daniell explains how both pavilions give different responses to the unification question. Hong Kong emphasizes its inclusion in a larger regional network, the Pearl River Delta, while Macau places focus on its cultural distinctiveness.