Hong Kong and Macau aren’t independent nations, yet they appear at the Biennale regardless. As recent appendages to China, they are undergoing an often-uncomfortable transition to a new political reality. Thomas Daniell explains how both pavilions give different responses to the unification question. Hong Kong emphasizes its inclusion in a larger regional network, the Pearl River Delta, while Macau places focus on its cultural distinctiveness.

Separated by an hour-long ferry ride across the mouth of the Pearl River Delta, Hong Kong and Macau are two tiny appendages to the People’s Republic of China, former European colonies that were returned to Chinese control at the end of the twentieth century but are not yet assimilated. Both territories have been given the temporary status of Special Administrative Region (SAR). Under the ‘one country–two systems’ policy promoted by Deng Xiaoping, Hong Kong and Macau are permitted to maintain most of their pre-handover identities: capitalist economies, democratic elections, colonial legal systems, independent judiciaries, along with unique flags, currencies, and postage stamps. On the mainland side of the SAR borders are Special Economic Zones (SEZ), Shenzhen adjacent to Hong Kong, and Zhuhai adjacent to Macau. The SEZs were established in the 1980s for limited experiments with economic liberalization, but now act as buffer zones that further distance the SARs from the mainland. More than provinces, less than nations, Hong Kong and Macau nonetheless remain separated from China by what are, for all intents and purposes, national borders: immigration checkpoints, customs controls, quarantine control, duty-free shopping, and so on. Chinese citizens require ID cards to pass into the SARs, and there are limitations on the frequency of visits they may make. Even so, last year more than 40 million mainland tourists visited Hong Kong, and almost 30 million visited Macau.

This ambiguous post-colonial, pre-repatriation status of the SARs is reflected in the peripheral positioning of their Venice pavilions. Categorized among the ‘collateral’ events taking place during the Biennale, Hong Kong and Macau have rented adjacent courtyard villas just across the street from the main entrance to the Arsenale – making them much more accessible and visible than, say, the China pavilion. For Hong Kong, this is the tenth participation here, for Macau the first. The two exhibitions are diametrically opposed in their treatment of issues of internal identity and external relationships: Hong Kong expands across borders to embed itself in the wider Pearl River Delta region, whereas Macau looks inward, focusing on details of its everyday environment.

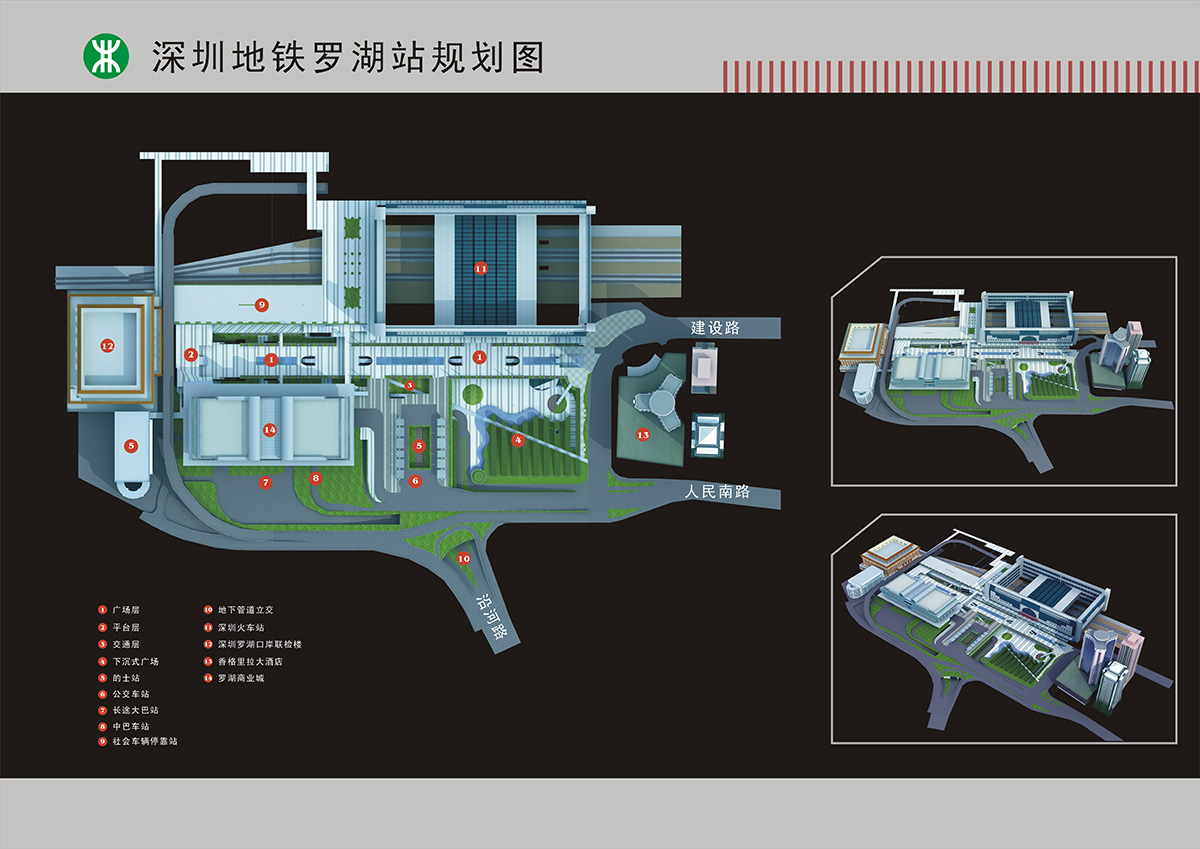

The exhibition title Fundamentally Hong Kong? DELTA FOUR 1984–2044 polemically positions present-day Hong Kong as part of a network of four major cities in the PRD (the others being Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Macau) poised between the preceding thirty years of historical change and the next thirty years of urban development. The exhibition is divided into four sections, each containing two architectural projects and a short film, thereby linking physical transformations of the territory to experiential changes for its inhabitants. Under the title ‘Borders/Connections’, models of massive infrastructural projects for Luohu Station in Shenzhen and Kowloon Station in Hong Kong are shown together with Wong Siu-pong’s Connection, a documentary on the lives of several women who emigrated from the mainland to Hong Kong. The section ‘Space of Remembrance’ contains examples of crematorium and columbarium projects in Hong Kong and Macau complemented by Chris Ng’s film Rest is Pending, the story of man touring the opulent columbaria that have appeared in Macau and the mainland in response to a shortage of public cemetery spaces in Hong Kong. The section titled ‘Reclamation’ contains Tsim Ho-tat’s film Over the Wall, the fictional story of a famous mainland theater director who comes to Hong Kong and hires an architect to design a wall that would separate the West Kowloon Cultural District from the rest of the city. It’s paired with models of the district’s future centerpiece, Herzog & de Meuron’s M+ museum, and the masterplan for Qianhai, a 15-square-kilometer development now under construction in Shenzhen. Once its high-speed rail links are complete, Qianhai will be only minutes away from Shenzhen airport and Hong Kong airport, and not much further from Hong Kong’s Central District. The section ‘Home and Community’ features Heiward Mak’s film SAR², which is set in a housing project in Qianhai. It’s the story of a Shenzhen woman whose oyster-farming village was cleared as part of a land reclamation project, where she now lives together with a Hong Kong man. Like other former villagers, they now have a luxurious new apartment, but are surrounded by vast construction sites, alienated from any sense of family or community. It’s shown together with projects for ‘sustainable public housing’ in Kowloon and a serviced-apartment tower surrounded by a farming village on reclaimed land in Guangzhou.

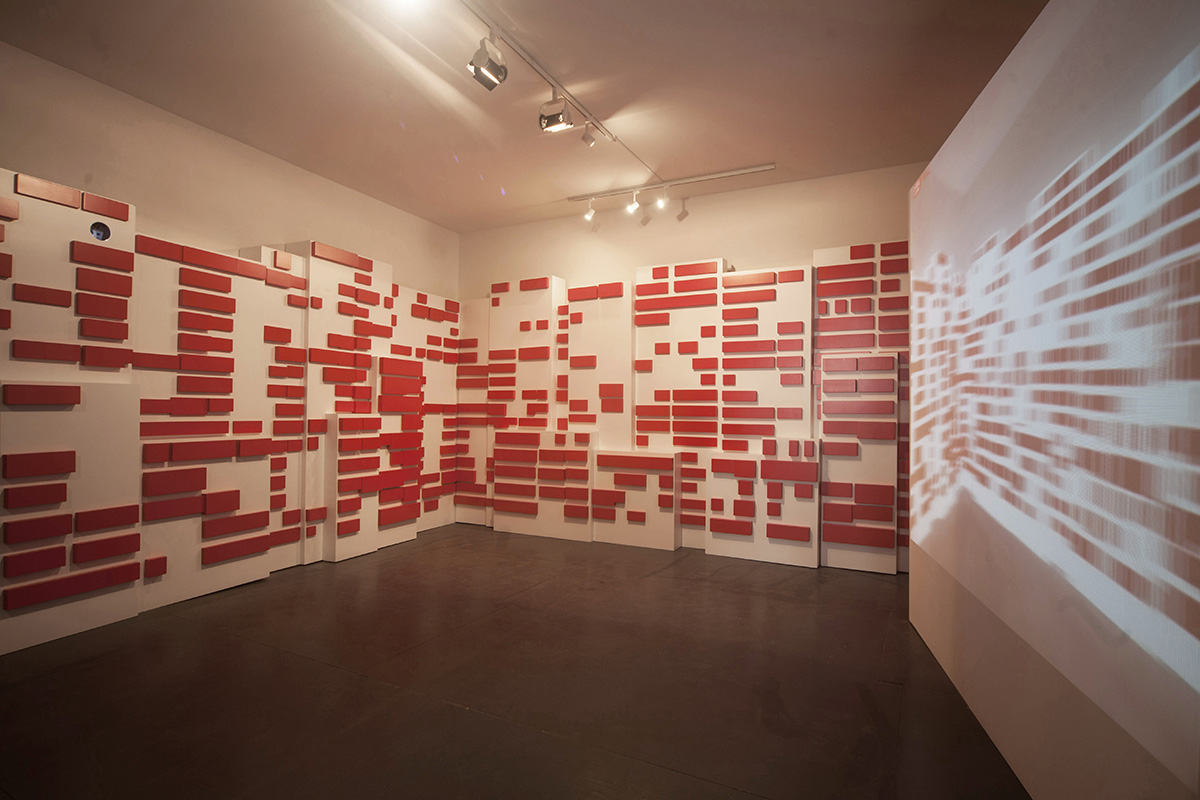

The Macau Pavilion’s Happiness Forecourt = Largo da Felicidade = 開心前地 (the trilingual title itself is a mini-manifesto for cultural coexistence) also comprises four independent parts, each contained in a separate room of the villa. Disconnected but complementary in their content, they are all expressions of the blending or superimposition of European and Asian cultures found in Macau. Three of the rooms are more like art installations: Low Stool? Yes, More! by Ryan Lai is an array of seats representing typical Macau coffee stalls, From Below to Above by João Ó is a graphic interpretation of the decorative patterns found in Macau’s temples and churches, and Listen to the Heart by André Lui is a aural collage of Macanese soundscapes. The fourth room contains the most clearly architectural project, The Added Layer by Nuno Soares. A response to the informal modifications made by the residents of older buildings, the installation is in three parts: a video documenting the patterns of metal cages added to apartment windows, a red-and-white wall relief that forms an abstract representation of those patterns, and a speculative ‘prototype’ frame for which other architects are now being invited, through Soares’s project website, to insert customized modular units.

Despite the overt differences in approach, these two pavilions have the same underlying theme: how to maintain a degree of local autonomy and identity as the SARs become increasingly indistinguishable from the mainland. The question becomes particularly pressing (or perhaps merely moot) in the knowledge that the SAR status itself will expire in the middle of this century. Hong Kong is shown preemptively surrendering to the inevitable networked urbanism of the Pearl River Delta, while Macau latches on to distilled versions of its local idiosyncrasies, but both suggest ways in which regional characteristics might be preserved and strengthened within the increasing ambiguity and irrelevance of the concept of ‘nation’.

This article was published in Volume’s 41st issue, ‘How to Build a Nation’.

This article was published in Volume’s 41st issue, ‘How to Build a Nation’.