Parallel Clouds

In early 2015 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the World Food Program launched biometrical cash machines for Syrian refugees in Jordan. This new format of digital purchasing power for food and shelter, where Cairo Amman Bank replaced card and code with retinal scans, has enabled refugees undone from their belongings to access financial assistance. The introduction of digital technology into spatial contexts of refuge mobilizes a virtual geography of information, such as how many refugees are there, how many are HIV positive or pregnant, and where are they moving to. By inserting digital technology in the process of basic aid, human rights have been transposed to the digital sphere, yet incorporating advanced digital infrastructures in contexts where bricks and bread would be more than enough initiates a self-eliminating hoax, seeing as how, frankly, it is the exact same digital technology that keeps famines in place, targets relief-hospitals with drones and leaves migrants to drown. When we are all just one scan and click away to be saved, are we also too easily and often left to fate?

As humans, we constantly shelter ourselves from exterior forces, be they meteorological, financial or social, but what does shelter mean in a boundless digital territory where operational systems like wifi-zones, passwords, satellite imagery and drones infiltrate our daily existence? Architecture has long been a profession dealing with shelter in both the built and the unbuilt, yet the integration of technology into our lives has sold our right to freedom and privacy under the auspices of efficiency and security. Safety derived from data collection is promising a false security if it is defined by the hands who own it. So it’s fair to wonder what exactly Cairo Amman Bank is getting out of aiding refugees? Our iris-scans, passwords and voicemails appear to be private but are in effect not even ours. Who actually owns the digital?

Through neoliberalism and digitalization, western countries shifted from being industrial manufacturers to service providers, however today, their economies are defined more by their status as digital provider and data collector – in other words, by their respective potentials to control and utilize. Rapidly developing informal economies such as Mexico or India have quickly caught up with these booming data-infrastructures, and their IT sectors now facilitate the massive offshore outsourcing of labor and services by the West. What results is a grey-zone of territorial data-ownership: when I use my British T-Mobile SIM card while travelling in New York to call Deutsche Bank in Berlin, a help desk in New Delhi picks up. My conversation, whose operation is owned by T-Mobile UK, is downloaded and transmitted by the American service provider AT&T and stored in India by its local equivalent, while its rights and content are owned by Deutsche Bank in Berlin, without ever touching German soil. While this is the legal route of data-mining, its raises the question of how the less than legal infrastructures of governmental surveillance used by the GCHQ or NSA operate.

When every sovereign state has its own space and set of rules, the transnational laws of data disobey formal jurisdiction and operate beyond physical or political geographies. Yet data does claim territory; its space and route however only surface when questioned through scandal and conflict. Therefore, if we acknowledge digital space as a territory in its own right – no matter it be in or out of sight – and we recognize the intricacies of data-ownership, we ought to keep on top of how this territory is understood and mapped. While data might not be considered a threat when it passes us by, it definitely is a force we cannot monitor and therefore cannot shelter from. With its direction and damage crystal clear to those who own, provide and profit from data, its space and route seem deliberately kept away from its subjects. But when scenarios of digital blackmail and data-leaks are omnipresent in our daily news cycle, its time to understand the hidden realities of our own data and consequently demand ways to shelter from the digital forces that obtain it. But how can one simultaneously find methods of shelter within this invisible territory, and find ways to shelter from this immaterial territory?

During the January 2014 social unrest in the Ukraine, digital borders became spatially manifest when cellphone users near the Maidan clashes received text messages saying: “Dear subscriber, you are registered as a participant in a mass riot.” Willingly or not, cellphone users crossed a border between the good and the bad Kiev. Putting the immense political consequences of this aside, having a mobile phone is as much of a political act as casting a vote or being a citizen. When during the Arab Spring, the 2011 London riots or even the more recent 2015 Ankara bombings, social media and digital access functioned as a thriving tool of civic control: Hosni Mubarak, David Cameron or Tayyip Erdogan’s best defense was not to drop bombs but to switch off the internet. Digital borders do exist, but are inherently contested and blur when they can be switched on and off by one or a few. Situations like this illustrate, as the work of Wikileaks and Edward Snowden demonstrate, that we are being watched over and controlled by governments we did not elect.

By 2020, 50 billion wifi-connected devices will be operating on planet earth, all collecting and transmitting data to not only their users but also manufacturers and network providers. Data and its surveillance is hidden on a much smaller scale than the internet at large; think of voice recognition, digital radio and pacemakers. Consequently our bodies and our homes are turning into data-factories, but somehow we are so obsessed with security we don’t notice the endless sensors, CCTV cameras and alarms already around us. When during the 2014 Venice Biennale Rem Koolhaas interviewed Tony Fadell, CEO of Nest, a company developing smart heating mechanisms, Koolhaas suggested that it was a small leap from a thermostat that knows how to save energy to one that says you have used enough energy for one day and shuts the system off. Do we keep turning a blind eye to digital technology when an incomprehensible force of data permanently pervades our selves and our homes? Alongside meteorological, financial and social storms, our biggest threat is data technology. Especially so when, according to Justin McGuirk, “experts evoke a cyber-security nightmare of ‘botnet’ armies using toasters to launch DDoS attacks” and we’re all still laughing at the thought of it.

Ironically, the data-leaks by Edward Snowden exposed that most of the data mined by the National Security Agency is done for the Department of Trade rather than for matters of national safety or security. Privacy researcher and activist Christopher Soghoian explained during the 2015 IDEAS CITY Festival in New York that “most of the NSA’s operations are not about terrorism, but about maintaining and facilitating a network of surveillance probes to provide access to who-ever, when-ever needed.” Its fair to say that the economic foundation of the West is built upon and sheltered by balanced political regimes, which is increasingly only achieved, as these leaks tell us, at the cost of us citizens being open and exposed to digital technologies that commodify our existence, safety and humanity. As our private lives have become eminently more connected and therefore hackable, this erosion of privacy alongside the centralization of control asks for an architecture of interplay; where space itself becomes a truly contemporary form of shelter as a technology and information system by doing the one thing that data cant do: have physical presence and change its mind.

A primal role of architecture is to allow people to access safety and shelter when desired, but access to digital safety and shelter can’t be obtained by way of bricks and mortar. So the question of architecture in the 21st century is how can a smart home, where all primal elements such as water, heating, light and ultimately safety and shelter are provided and monitored by digital infrastructures, outsmart itself? Undone of privacy, kicked out of our mortgaged houses, blown away by storms and monitored by digital technology, shelter today really is a privileged term that most of us can’t tap into. And with both its material borders in flux and digital borders clouded, the right to shelter has become the most contested of all human rights. Yet shelter it is also the only properly spatial human right, and as such, architects not only should to respond to these spatial consequences, but are privileged in doing so.

Historically, architectural forms have been used to protect and prevent from danger; the built world has acted as a sheltering mechanism. The insertion of technology in our economies and societies has done this, but also brought along with it repercussions. As Paul Virilio argues in Politics of the Very Worst: “when you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution …”. When in 1838 the English scientist Michael Faraday invented the dynamo as the first crude power generator that stores electric transmissions, he at the same time invented the Faraday cage, a shield of conducive mesh that blocks electric transmissions – or lightning strikes for that matter. Since then, the typology of this architecture, a mesh shield, has evolved to shelter us, be it in a cage, car or aircraft.

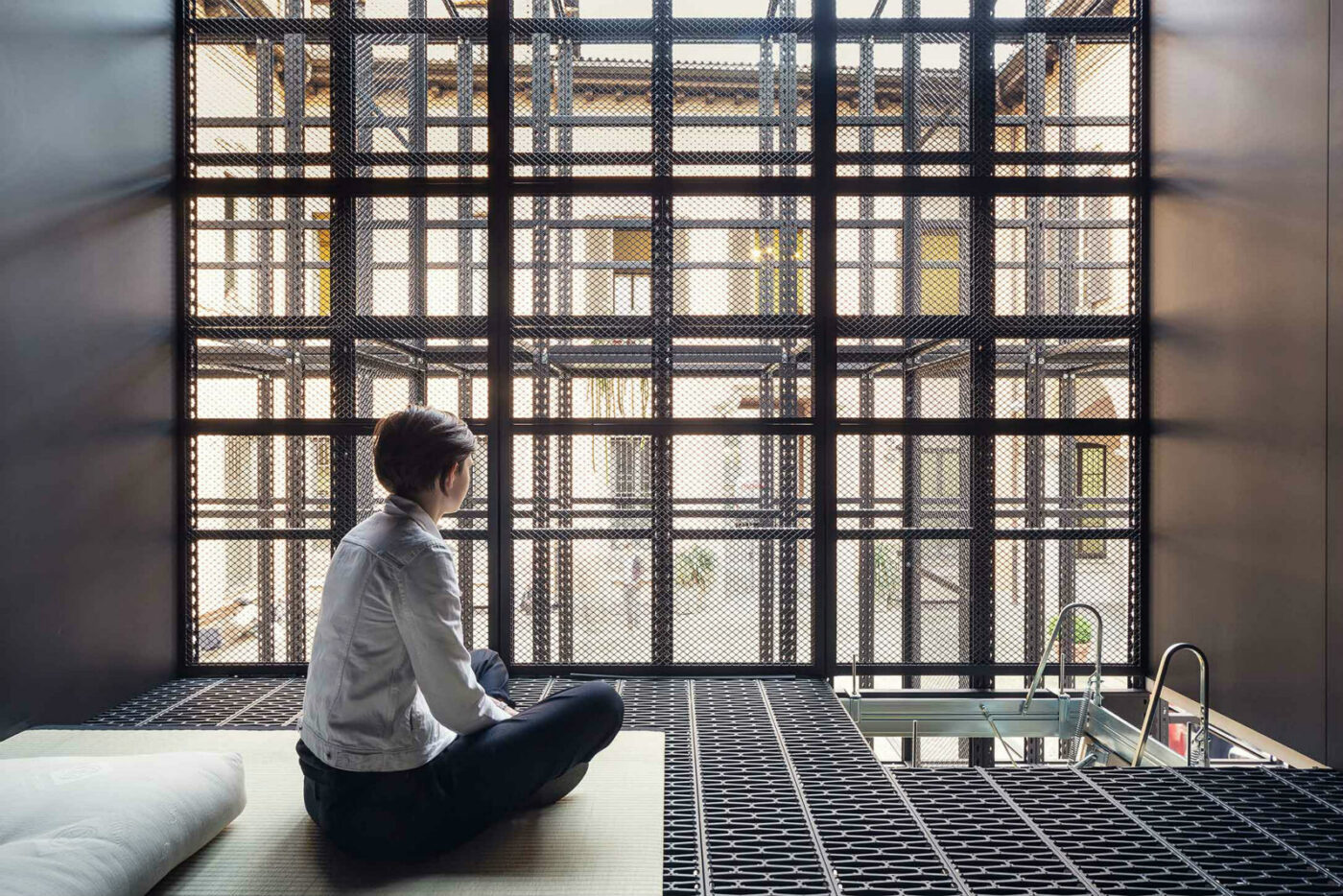

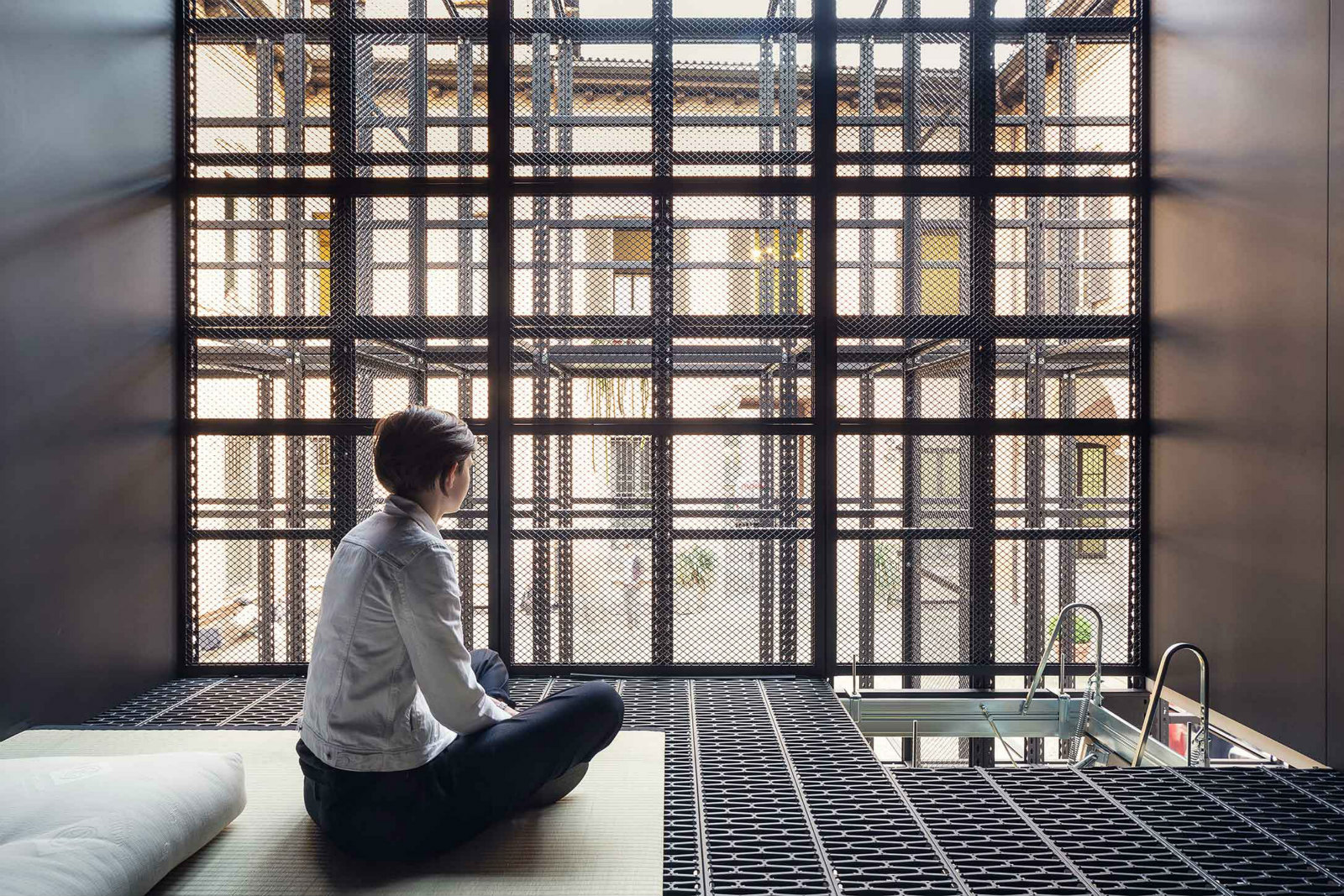

In 2014 Space Caviar developed the RAM House, a domestic environment made out of a series of movable shields of radar-absorbent material (RAM) that selectively filter incoming and outgoing signals of data transmission. The design resembled Faraday’s typology of the cage, however where a Faraday mesh permanently blocks electric transmissions, Space Caviar’s enclosure is unique in its ability to propose variances of shielding. Through enabling a selective interface of blockage, variable levels of privacy are obtained – today I would like to have the light on, tomorrow I would like to receive my emails, or wait, maybe I just want hot water? Creating a certain type of negotiable privacy is much needed when “wifi and cellphone signals pass through walls effortlessly leaking onto the street and to the apartments around us.” The importance here is the unpredictable desire for privacy that the RAM House – or RAM Cage – resident-user can determine on a minute-by-minute basis.

The architecture of the RAM House, made of shields and cables, seems tech-savvy and its appearance perhaps too prison-like to be considered shelter, but when a court hearing in Colorado in 2014 revealed that local police used radar devices to remotely search a house and arrest a man wanted for violating his parole, its importance comes to bear. The contested Range-R radar allows the detection of movement and bodies through a wall as thick as eight inches without entering. In the court hearing, the judges explained that when governments use such powerful tools to search inside homes without search warrants, it is violating the Fourth Amendment, the right that protects citizens and their private property from being unreasonably searched and seized by the government. Ironically, drones are still spying and killing people without notice, process or trial, the NSA records every phone call made by US citizens, and searches at the United States borders may be conducted without a warrant. When systems of surveillance are permanent yet immaterial, is the only true shelter to hide behind material shields that operate unsystematically?

When earlier this year Andrew Herscher introduced the term ‘digital shelter’ as a mechanism to mobilize the disenfranchised, his wording embarks on a dichotomy of shelter being a material barrier and a digital one pertaining to immaterial access. The contradictions between shelter and the digital linger, both in time and durability, and privacy is a term that has heavily changed its meaning and relevance over time. In her 1958 book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt recalls the ancient Roman notion of privacy being not private how-we-know it, but rather a temporary refuge from the business of the republic, and that “a man who lived only a private life … was not considered fully human.”

Centuries later, in our modern, individualized, connected, neoliberal societies, we demand the right to privacy, we demand the right to access, we demand the right to shelter and demand the right to freedom, but somehow we forget to negotiate the implications of our citizenship. Consequently, when we roam data with our iPhones while travelling through Sudan or Russia, we take the territorial implications of what it means to be sheltered for granted. Shelter itself is being neither a thing nor being, but rather a condition. When in 2014, Jennifer Lyn Morone, an American student at the Royal College of Art in London, became a corporate entitlement (Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc) in order to protect and own her own data, questions emerge whether we as individuals are stronger protected when speaking the same language as our watchdogs. But can becoming a legal structure to shelter from legal structures really be the future?

The integration of digital technology in our private homes and lives forced a lobotomy in our understanding of safety and well-being. We can no longer wait to beat the legislation and economics behind surveillance or wait for the ultimate software update to encrypt our iPhones or MacBooks – a type of shelter that only the very few can afford. Shelter as such should be found as a condition undone of any spatial or time-based elements. The quest for what this shelter could be is of great importance, especially so when the most secured and surveilled places in this world, such as embassies, banks or jails, are under constant attack; while the thick cables running along the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean that carry and provide all the world’s emails, searches, phone conversations and Facebook messages are increasingly exposed to the public due to the erosion of beach-material. Have we lost our case when even the meteorological storms are catching up to the digital storms? Or is mass surveillance becoming such an integral part of our societies and democracies, that terms like shelter, similar to privacy, are changing their very meanings? Shelter, what was once about providing safety and humanity, might now take to challenging both the meaning and means of those two terms by way of counter-control.

References

1. “[FISA Amendment Act of 2008] enabled, without an individual warrant from a court, collection on U.S. soil of communications of foreigners thought to be overseas, including when the foreigners are communicating with someone in the United States.” Craig Timberg, ‘NSA slide shows surveillance of undersea cables’, Washington Post, July 10, 2013. At: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/the-nsa-slide-you-havent-seen/2013/07/10/32801426-e8e6-11e2-aa9f-c03a72e2d342_story.html (accessed October 26, 2015).

2. Julieta Aranda & Ana Teixeira Pinto, ‘TURK, TOASTER, TASK RABBIT’, e-flux, 2014. At: http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/tuned-to-a-dead-channel/ (accessed October 26, 2015).

3. Evan Rawn. ‘Video: Rem Koolhaas and Nest CEO Tony Fadell on Architecture and Technology’, ArchDaily, January 4, 2015. At: http://www.archdaily.com/583642/video-rem-koolhaas-and-nest-ceo-tony-fadell-on-architecture-and-technology (accessed October 26, 2015).

4. Justin McGuirk, ‘Honeywell, I’m Home! The Internet of Things and the New Domestic Landscape’, e-flux, 64, 2015. At: www.e-flux.com/journal/honeywell-im-home-the-internet-of-things-and-the-new-domestic-landscape/ (accessed October 26, 2015).

5. ‘Full Disclosure and the Morality of Information’, IDEAS CITY Festival, May 28, 2015. At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Acihg4pAUEc (accessed October 26, 2015).

6. Paul Virilio, Politics of the Very Worst (Semiotext(e), 1999).

7. Antonio Pacheco, ‘Signal-Blocking Structure Takes You Off the Grid—In Your Own Crib’, The Creators Project, June 7, 2015. At: http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/signal-blocking-structure-takes-you-off-the-grid-in-your-own-crib (accessed October 26, 2015).

8. Andrew Herscher, ‘Humanitarianism’s Housing Question: From Slum Reform to Digital Shelter’, e-flux, 66, 2015. At: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/humanitarianisms-housing-question-from-slum-reform-to-digital-shelter/ (accessed October 26, 2015).

9. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958).

This article was published in Volume #46, ‘Shelter’.

This article was published in Volume #46, ‘Shelter’.