Practices of Decentralization

Practices of Decentralization

Vinay Gupta interviewed by Ben Vickers

Ben Vickers – Curator of Digital at the Serpentine Galleries and initiator of unMonastery – sat down with Vinay Gupta – one of the world’s leading thinkers on infrastructure theory, state failure solutions, and managing global system risks – to speak about practices and politics of decentralization. In 2002 Gupta invented an open-source solution to ‘house the world’. The hexayurt shelter is designed to be manufactured anywhere in the world at any scale and from local materials.

Vinay, could we start by you saying a little about yourself, the route you’ve travelled, and how you found yourself involved in such an expansive cross section of disciplines – from cryptocurrency, through energy policy to global resilience, crisis management and way beyond?

I guess my life divides into two compartments. There’s a traditional Hindu religious stream, and what I did in that stream was 10 years of meditation, found a guru, and got enlightened, got certified to teach and then didn’t.

And on the other track, I started out in computer graphics, helped to invent the world’s fastest medical rendering algorithm in ’92, and then stayed in industry for about 10 years doing a variety of jobs along that kind of line, then switched to energy policy. The switch to energy policy happened by coincidence, but it put me at Rocky Mountain Institute, which is Amory Lovins the chief scientist’s kind of wizard’s tower, and Amory is the greatest energy policy theorist in the world. So, I absorbed an enormous amount of energy policy and then began to apply it in other areas, particularly poverty and sustainable development. Out of that’s come a variety of interesting work, as work on literal physical sheltering, some work on mapping and modeling critical infrastructure and an enormous amount of crisis and contingency planning work.

So, Amory built an infrastructure model that was used for analyzing how stuff works at RMI, and that infrastructure model was very simple. If you take a physical building in an American context, it’s got seven connectors to the outside world: clean water in, grey water out, black water out, electricity and natural gas in, transport and telecoms, and in most instances you can physically see this stuff. If you look at a house, there’s a trench, and in the trench there’s a bunch of cables and pipes and wires, and you can literally see the umbilical cables that connect the house to market capitalism; money flows in one direction, services flow in the other, and there’s complete clarity about those structures.

Some of them are connected to the state, in the form of say transportation or telecoms are often state modulated, and then some of them are usually done in a kind of “free market” context. So, I looked at that and was like “Okay, but if you’ve got solar panels on your roof in Africa, then you’re getting rid of these attachment points”, but also the political structure changes. The RMI story didn’t really talk about the politics in any real detail, it was very much about assuming the government stays stable, assuming that everything is done by things like auctions for bandwidth spectrum. But when you looked at areas where the state was very weak, the RMI models really didn’t extend into that territory in a very helpful way.

So you did something in response?

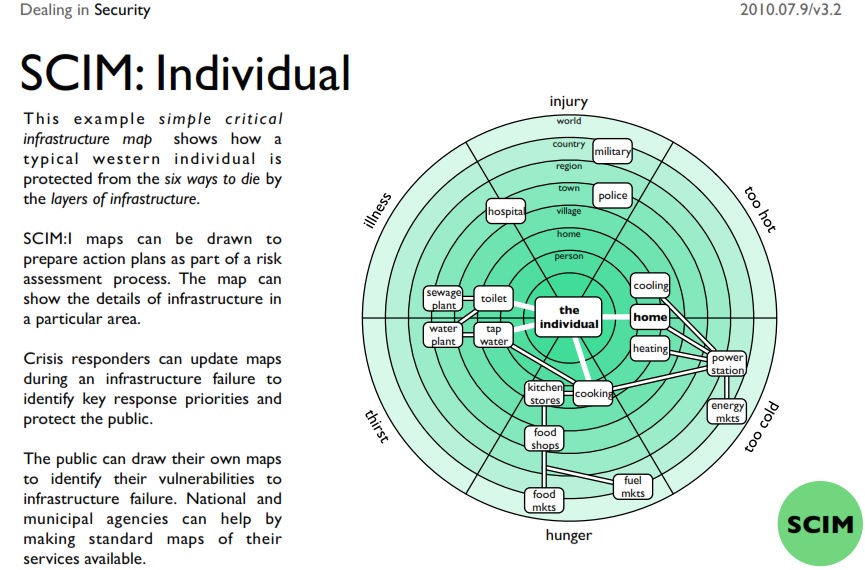

Well, at the same time, RMI was conducting research into autonomous building , and so I basically took this research and recontextualized it from a future America to, let’s say, a future Nigeria, and in that step I had to rebuild the governance model. What came out of that is this thing called SCIM, Simple Critical Infrastructure Maps, which is an 18-point checklist, and if you analyze a situation ticking off those 18 points, at the end you end up with a fairly comprehensive assessment of what’s keeping human beings healthy and happy in that environment, or alive if it’s a crisis. The 18-point checklist divides up into four groups, and this was very much cognitive design. What I wanted was seven, plus or minus two, as a handle, so that you could fit the entire system into working memory, even if you weren’t very educated or very smart. It was designed so that tired people in a crisis could remember how to get through the checklist, and as a result it would avoid entire classes of error.

The checklist starts with the individual, then it goes to group, then organization, then state, working up towards larger social complexity. The prerequisites for an individual to exist are that they can’t be too hot, too cold, too hungry, too thirsty, they can’t be ill, and they can’t be injured. That six-pattern template is called ‘Six Ways to Die’, which also shows up in a diagram that’s often called the dartboard of death, because it looks a bit like a dart board. The six segments around the dartboard are different threats, and then the rings that go out from the center are the tiers of political organization that protect you from that threat. So, if we’re dealing with too cold, your clothes are what prevent you being too cold, and your clothes are hopefully exclusively under your administrative control.

Then there’s the house that you’re in, and the house is frequently shared with people – your family, your friends – so you have a group dynamic that generally controls the house. Outside of the house you have a set of cables, as discussed, that connect you to the power grid that provides the heating for the house, and all that stuff is running at an organization level – there’s a big company that does that – and then you’ve got international markets which control the supply of fuels backwards and forwards between countries, and those fuels are bought by the organization to produce the warmth that keeps you alive, and this is where the state comes in – in some countries you would actually have state operators who provide you your national electricity.

All of those systems tie together so that you can track what’s keeping you warm right now, right the way up to the state level. In the original version of SCIM I had a level beyond the state that referred to nature itself, and then you could say that, fundamentally, at the beginning of this, all heat comes from the Sun, all cold comes from the vastness of space, but this was a little bit gnostic for people. Even though it’s a really good explanation why solar panels work, there was still a real problem that when you put absolute nature clearly on the reality map it just freaks people out, even though it’s a simple physical truth. When you look beyond the state to something above the state and beyond the state, nature itself and all the rest of that stuff, people act as if you’re gnostic.

Or practicing Egyptology.

Egyptology is very practical if understood, correctly.

Okay and it’s within this model of system analysis that the hexayurt is developed?

Actually it was invented first, and with one hexayurt… designing the infrastructure package around one hexayurt isn’t very hard. As I got more comfortable with the idea that the hexayurt was actually going to succeed, I started trying to visualize how you would design systems for the deployment of 100,000 hexayurts, and I realized: “this is a city, you’d have hundreds of thousands of people living there, it’s bigger than some countries, like Iceland. How do you even begin to design infrastructure for an environment like that?” and what I realized was that there is no objective tool for designing the infrastructure. Like, how do you tell whether you’ve provided all human basic needs or not? And it turns out that at the time there was no reference standard.

The Sphere Project standard now says how many square meters of shelter per person and all the rest of this stuff, but it doesn’t specify for example minimum or maximum interior temperatures. That’s really problematic, because it means that there’s no objective way to evaluate whether a shelter system is good enough for a given climate, because if you don’t specify how cold it’s allowed to get, how do you say this shelter is fit for purpose, if these people freeze to death? So, as I looked around I discovered that there just wasn’t an objective standard for figuring out what we should be giving people, and the result was that people were just making up as they went along usually on the basis of prior experience, and I thought “That isn’t good enough – we need something better.”

So, I sat there trying to figure out what the actual invariants in a disaster were that we could design backwards from, so I started with human biology. To understand what it takes to keep somebody alive in a minimal sense and then ask: “Okay, what happens next? Well, then humans form groups. What are the prerequisites for a group to exist? Can I work my way up from there?” kind of stack-wise, and at the top you get this question “What is the state?” and I’ll come back to that in a little while. But, none of this holds together if you use a Weberian definition of the state. If you think of the state as having a monopoly of force then SCIM doesn’t work, because it defines the state in a way that requires it to look a particular way, and this is the equivalent of defining a house by the pipe and wire harnesses we would typically use in Western suburbia.

So, the Weberian model of the state maps to a Westphalian model in a kind of post-industrial sense – industrial, post-industrial – in the same way that the RMI infrastructure model assumed a house that has pipes and wires. And, of course, the RMI people were all about getting rid of the pipes and wires and so on, but if you frame it as pipe and wire you’ll still wind up in a position where you’re confused, because we’re looking at the infrastructure from the perspective of an architect rather than looking at the infrastructure from the perspective of an inhabitant. It’s this kind of person-centered thing that maybe I picked up from Rogerian psychotherapy, but it’s this person-centered approach that really guides SCIM.

And also within that has assumes a position of decentralist politics.

It certainly allows for it. I mean, if your critical infrastructure is being maintained by a state, there is no decentralization; if they don’t like you – as they did in Suez – they’ll just turn your water off, and when you get thirsty you’re going to come back to being a good little citizen, or you’re going to die. So, decentralization of infrastructure is more or less a prerequisite for any kind of non-violent revolution, and any violent revolution is typically going to focus on controlling the critical infrastructure first. If you’re having an uprising, and the state controls the power stations and the water, you know, your uprising isn’t going to last very long. So, it’s very clear that in the modern world fighting for control of critical infrastructure is what hot war is really about. Oil, right? It’s critical infrastructure. “How do we get ahold of the oil?”

I wanted to take a moment to focus on the root motivations for the hexayurt’s development, in order to illuminate the kind of culture that prefigures it, whether that’s free hardware, whether it’s the idea of one world and one set of resources, appropriate technology, Burning Man. There are a lot of cultural signifiers within the hexayurt ecosystem and the conditions that give rise to you developing the hexayurt, and I thought it would be useful to sketch that out further, it’s historical precedence.. Previously we’ve discussed the notion of a bottom-up stack as the antithesis of how the majority of the infrastructure that surrounds us to do is achieved through top down central planning.

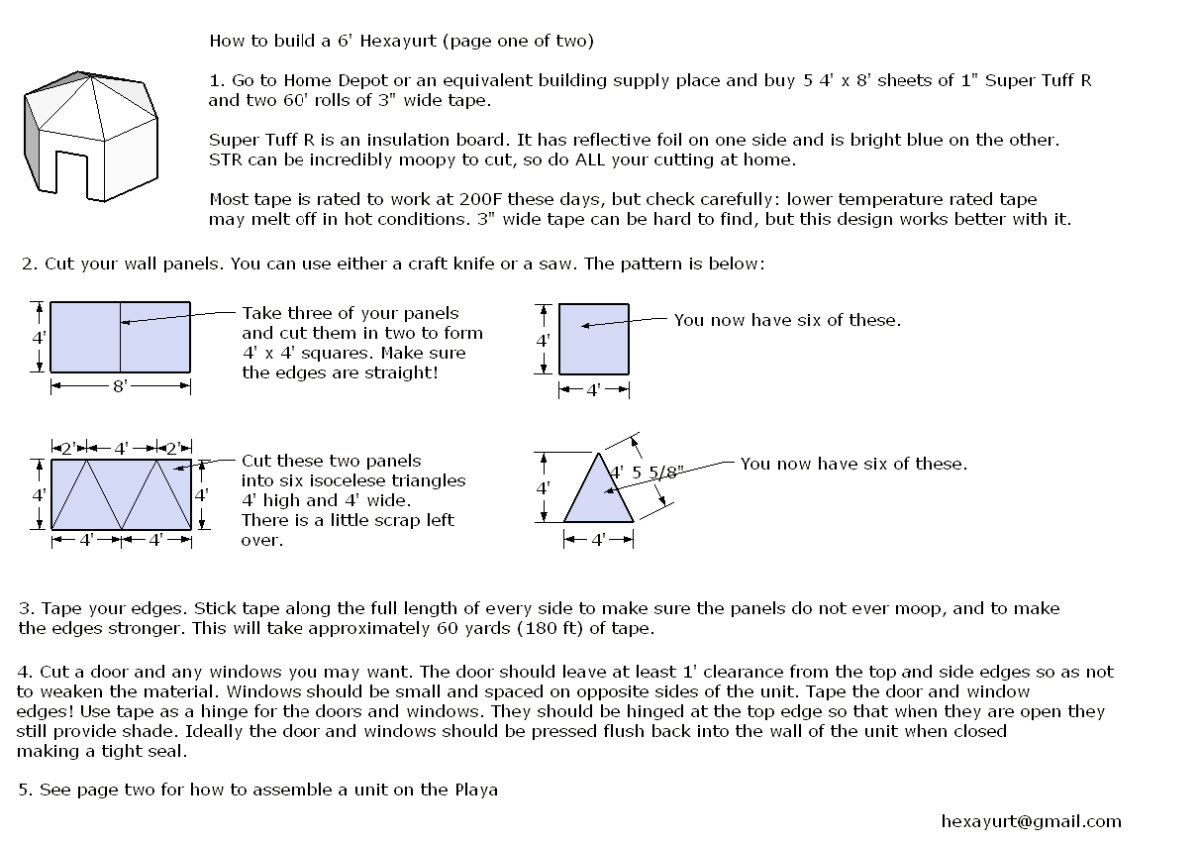

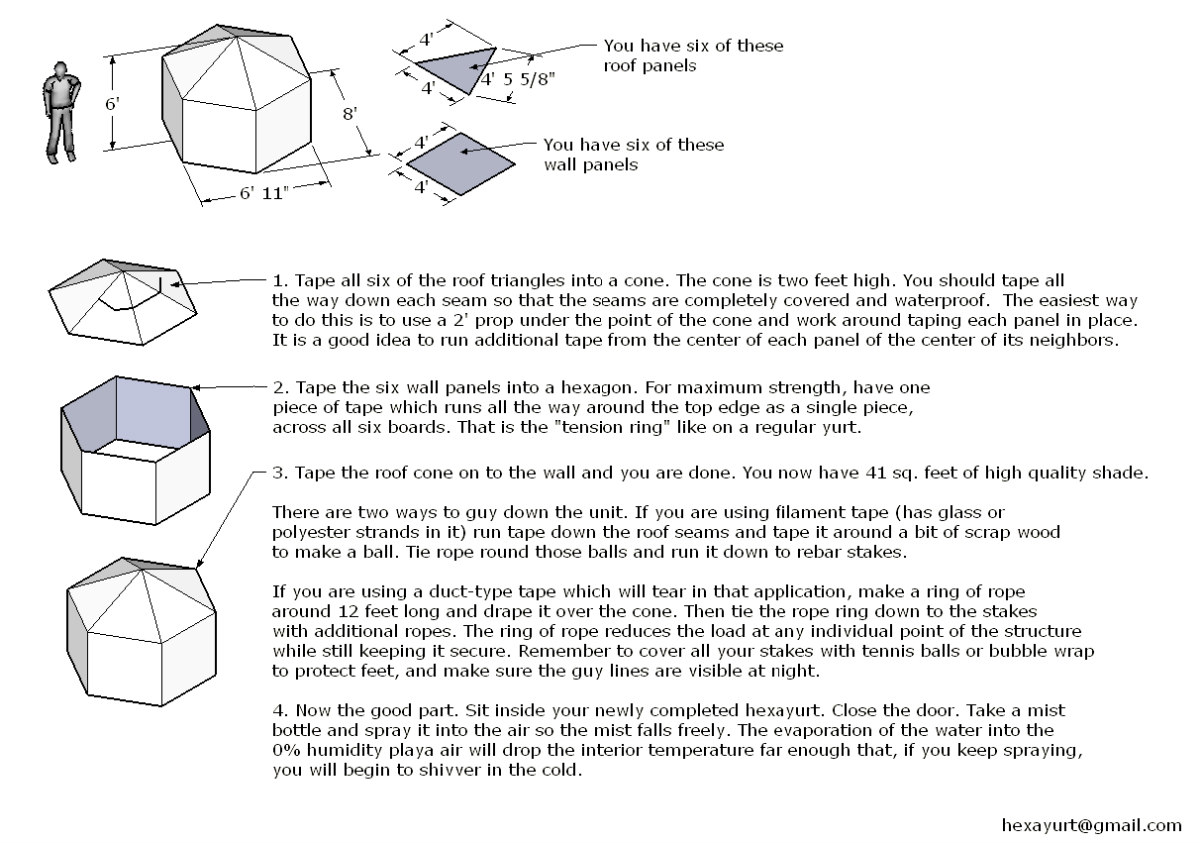

The hexayurt gets started directly as a result of my fascination with the hippies in the 1960s and the whole 60s culture system movement. In 1995 I go to visit The Farm in Tennessee. The Farm was the biggest hippy commune in America, 15,000 people incorporated into a religious order with fully shared property; you joined the farm, they took everything you owned, and they said they’d provide for you for the rest of your life, and they managed for 15 years before they went bankrupt. But it was open door; anybody could join pretty much. So, I get to The Farm, and I get into a conversation with Albert Bates of Worldwatch who says “Vinay, you know a bunch of triangle math, don’t you, from all this computer graphics stuff? Could you figure out how to make a geodesic dome with no waste? We build them on the farm sometimes and you get twenty-five to forty percent waste, because when you cut the dome triangles out of plywood sheet there’s lots of leftover.”

So, I sit down for about six months off and on, cranking out spreadsheets in Visual Basic, redoing Buckminster Fuller’s math to try and figure out whether it was possible to fit Fuller’s triangles onto plywood any better than in the ways that we were doing. I came up with one, tiny optimization that saved five to eight percent, and I corrected a typo in a 30-year old Fuller pattern, which I considered to be useless; just no progress, the problem is too hard – forget it. I come back six years later, when somebody at RMI says that they’re doing a conference on refugee stuff called ‘Sustainable Settlements’, and asked if I know anything about refugee shelters? Could I design a shelter? “You’re an engineer, Vinay – you can do stuff, right? Can you design a shelter that could be packed flat on a truck and transported with the refugees, so that when you resettle them you can move them?”

I sat down with a bit of paper, and what came into my head was a question that we often ask in software, which is: what is the simplest thing that could possibly work? I drew a sheet of plywood, and divided it up into some one-by-two triangles, and then I put six of those one-by-two triangles together into a shallow cone, and there was a hexagon. Then I sort of said, “Well, put a wall underneath that, that’s a small hut.” – boom: there’s a hexayurt. And I called that a yurt rather than a dome because the dome was widely understood to have failed, and people were much more sympathetic towards the yurt; but, you know, really it’s a dome. It’s got some of the structural properties of a yurt in that it’s dependent on, but it was specifically a break with Fuller’s naming of things, because although Fuller is right about almost everything, he’s also got terrible PR. And I think this is because, frankly, when you read Fuller you feel dumb. Fuller is really, really, really, so very good at communicating in very complicated ways; almost everybody is intellectually intimidated by Fuller, which is why Fuller has so few friends.

So, I come up with this thing, the hexayurt, and then I started thinking about how I’m going to deploy it, how I’m going to get this thing to scale, and what I realized is that the history of patent shelters is total failure. People start a company around some new idea, they raise a bunch of money, they go two or three years in business, they sell a few thousand units a year, then they run out of money and go bankrupt. The reason for this is that the shelter business is extremely irregular; you’ll wind up with huge orders and then no orders, then huge orders and then no orders, and the cash flow just destroys your company. So, at that point nobody had really done open hardware. Nonetheless, I put the designs online. I formalized it – there’s no copyright and no patent – in 2005, but everything had been published before that, and then I take one to Burning Man in 2003. Without Burning Man there is no hexayurt project. They’ve got a lot of money, really a lot of money – I’m told that billionaires have actually slept in hexayurts at Burning Man – they’ve got an acute need for shelter, and they don’t like RVs.

I built the first one and people looked at it and were like “Wow!” I went back a couple of years later with some more, went back a couple of years later with some more. In 2006 there was a large installation called the Axial Temple. Then they jumped because of a Wired article in 2010, and suddenly the number of hexayurts on the playa went from maybe 50 to 500 – there was a huge jump; we could see them on the satellite pictures. And after that jump it’s just become entwined with Burning Man as a standard piece of technology. But in any given year you’ll get maybe half a dozen or a dozen hexayurts built outside of a Burning Man context, and at Burning Man the number being deployed is doubling every year. And then what’s happening is that people are taking them home and living in them at home.

In the communes up and down California, apparently quite a lot of people live in hexayurts year round, and all of that is knocking the bugs out of the system. It improves the technology, it improves the infrastructure, improves the building, improves the building instructions, improves the choice of materials, because we’ve got real users from that kind of fringe culture. But is it really fringe, if it’s the home of Silicon Valley? Maybe they just mean futuristic. But because we’ve got a core user group in that department; we can afford to run the project without external funding, because our R&D funding is coming from our users building their own units and innovating. So, all the work that’s been done on the design could be repurposed in quite a few emergency situations, and it’s all been done – it’s open R&D.

There’s something that I wanted to touch on that you’ve mentioned before, particularly given that companies like IKEA have recently dropped millions of pounds on the development of refugee shelters, given the current situation.

The IKEA shelter was very nearly a hexayurt. Johan Karlsson, who’s the designer and project manager for the IKEA shelter, worked on and off with me for a couple of years building hexayurts in Sweden, and when the IKEA money showed up suddenly he didn’t want to know my name anymore. We could have built the hexayurt as the IKEA shelter, and I think IKEA would have been far happier with that, but because of kind of personal-political rivalry between designers we wound up with a closed source shelter that frankly is far inferior to a hexayurt, because it’s got five times the component count. I believe that the actual decision, finally the thing that kicked it over the edge, was that the UN wanted something that looked more like a tent. But because I was taken out of the political process by Johan, I wasn’t able to advocate for needing something which is efficient in mass production, something that uses IKEA’s existing infrastructure and supply chains.

What I would have done is build a shelter that IKEA would have not needed to build a custom factory to produce, that they could have run directly off their existing production lines with only very small alterations in a crisis, so you don’t need any heavy capital investment to be able to maintain the capacity to build enormous numbers; when you get a crisis you simply have a smaller availability of very large tables for a few weeks. Because IKEA’s already handling such an enormous volume, producing, you know, 50,000 hexayurts a day is probably not out of their capability, if they go flat out. It might be 50,000 a week.

They could certainly ship that many catalogues, given that their yearly print run now outstrips The Bible.

And, you know, think of the volume they’re doing out of their stores. Now, obviously better for a domestic disaster, but if you imagine IKEA as this flexible supply chain that runs halfway around the world, then the notion that if you can design something that can be built using their existing tooling, you don’t need to stockpile and you don’t need to premanufacture; you just flip some switches in their manufacturing capacity, and you go from one product to another. They’re doing it already for lots and lots of products. “We need more tables, we need more wardrobes, we need more this, we need more that. Well, today we need more hexayurts.”

If you could get the tooling to be exactly the same as the current industrial tooling, you don’t need to stockpile and you don’t need to capitalize; you build as required. And that was always at the core of the hexayurt vision. This is why IKEA was so exciting for me, it was the possibility of taking somebody that’s already working in huge, flat pack boxes, and shipping one more product in their line; instead they’ve got a whole bunch of custom capacity which doesn’t work. Hence, they’re doing five to ten thousand units a year, it doesn’t scale because it’s not efficient – back in the patent shelter cycle.

And eventually – you know, this is the way history goes, right? – the technology that actually works eventually scales, and all these little side branches then kind of wither. That kind of historical trend is incredibly important to understand when we’re talking about the politics of technology. Eventually we conform to the efficient engineering solution more or less whether we like it or not; economics and expedience force us to it. But it’s always much slower than people expect.

This article was published in Volume #46, ‘Shelter’.

This article was published in Volume #46, ‘Shelter’.