Total Space

Total Space

Dirk van den Heuvel

As introduction to the Total Space insert in Volume 50, Dirk van den Heuvel links (Dutch) Structuralism to current day developments, more specifically in the digital realm. Total Space is an ongoing research project of the Jaap Bakema Study Centre*, that’ll produce program and public presentation at Het Nieuwe Instituut in the coming years. It takes a closer look at the international dimensions of structuralism and cross-disciplinary exchange between the fields of architecture, planning, systems theory and anthropology. It also aims to connect the recent history of the 20th century with speculations on the future of our lifestyles in the 21st century city.

Throughout his life the Dutch architect Jaap Bakema (1914-1981) sought to convey to his students and colleagues the notion of what he called ‘total space’, ‘total life’, and ‘total urbanization’. In his view architectural design had to help in making people aware of the larger environment to which they belong and in which they operate. Architecture could not be uncoupled from urbanism, it was related to the deeper structure of society. His conceptualization of architecture was programme and process based and it put social and visual relationships at the centre, which betrays his adherence to Structuralism as voiced in the Dutch journal Forum of which he was an editor together with Van Eyck and Hertzberger, and to the Team 10 discourse, of which he himself was one of the leading voices. At the same time, Bakema would expand on the legacy of the Dutch De Stijl movement and Dutch Functionalism. In particular his concept of space and spatial continuity is derived from De Stijl. His diagrammatic approach to architectural design and programmatic organization, as well as the elementary architectural language of his projects were elaborations of the Dutch Functionalist tradition.

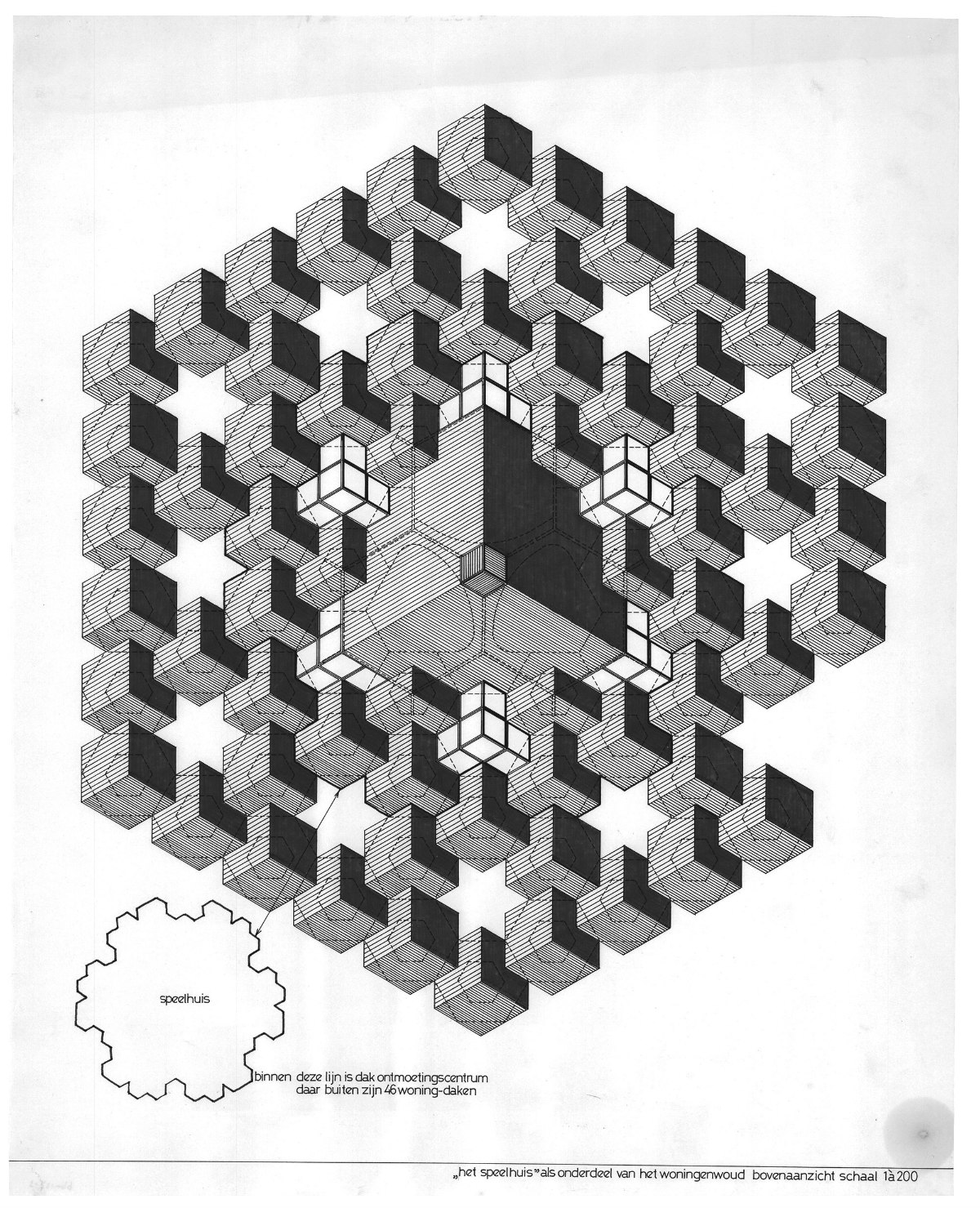

Blom drew the roofs of the theatre with some of the surrounding 188 houses. The star-shaped void for admitting daylight is created by omitting one cube.

(Source: Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, Blom, P. / Archive (BLOM), inv. nr. BLOM137)

Particular to Bakema’s approach, and his friends of Dutch Forum and Team 10, was the way these theoretical notions were articulated architecturally as an interrelated system of transitional spaces, elements, filters et cetera, from the doorstep to the street to the larger city and the landscape. For Bakema cum suis, such a socio-spatial system of relays and switches would allow for the citizens to navigate the post-war realities of a new emergent consumerism and state controlled planning by individual option. However, within the context of the welfare state, that established a redistributive bureaucracy of resources, industrial production and wealth accumulation, the ‘total’ aspect of the new environmental thinking all too often yielded egalitarianism and free-choice to apparently ‘totalitarian’ planning practices of pre-programmed encounters and choices. It wasn’t until the 1970s when the seemingly endless expansion of this economic system broke down and a new regime based on the so-called free-market ideology replaced the old redistributive system.

Megastructure

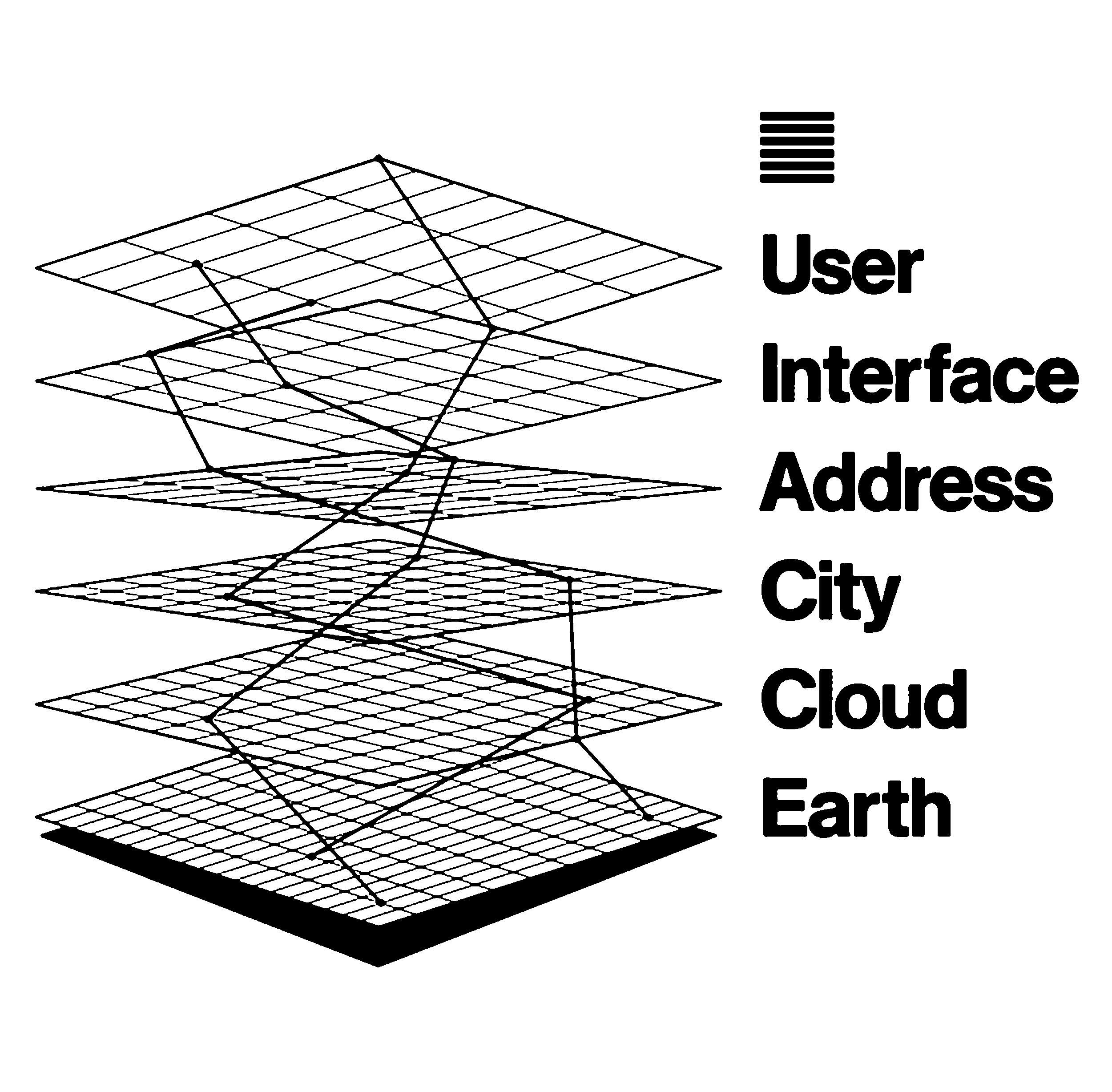

‘Growth and Change’, ‘Habitat’, ‘Ascending Dimensions’ and the ‘Aesthetics of Number’ were all key terms that Bakema linked to a political programme for a social-democratic, egalitarian and open society as embodied by the Western European welfare state system. Other words of the period that were most characteristic of the avant-garde circles in which Bakema moved, included the by-now familiar ones of ‘network’, ‘patterns’, ‘environment’, ‘metabolism’ or ‘ecological urbanism’. While the welfare state system has withered under the rise of neo-liberal politics, many of these historical terms from the 1950s and 60s are still current in describing the transformations of our urban lifestyles and environments under the influence of new digital information technologies. Most notably, in his recent book The Stack, On Software and Sovereignty digital design theorist Benjamin Bratton uses one of the foremost architectural concepts of the 1960s when he speaks of an ‘accidental megastucture’ to explain the conglomerate of ICT-infrastructures that created a new ‘global’ reality.

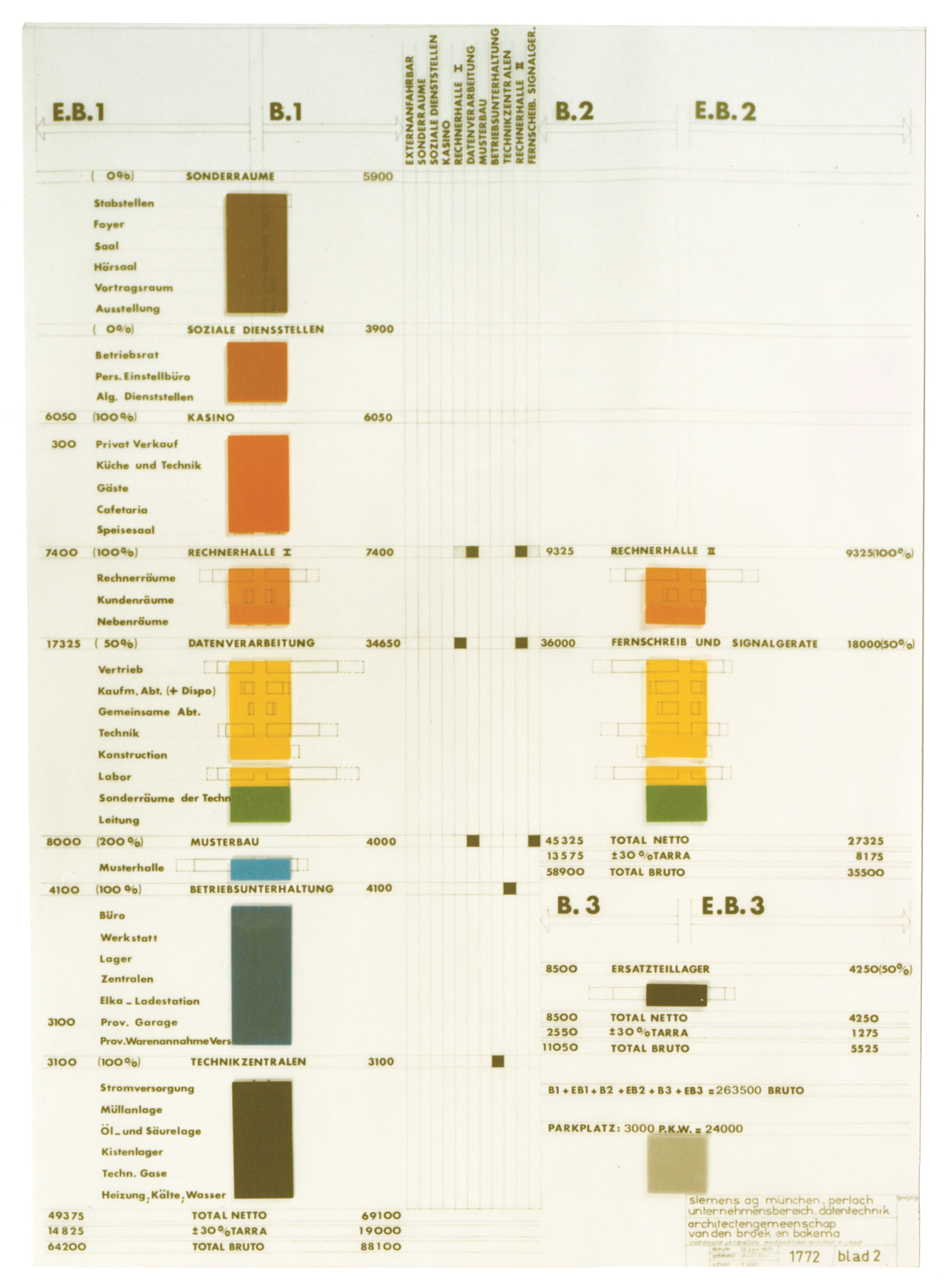

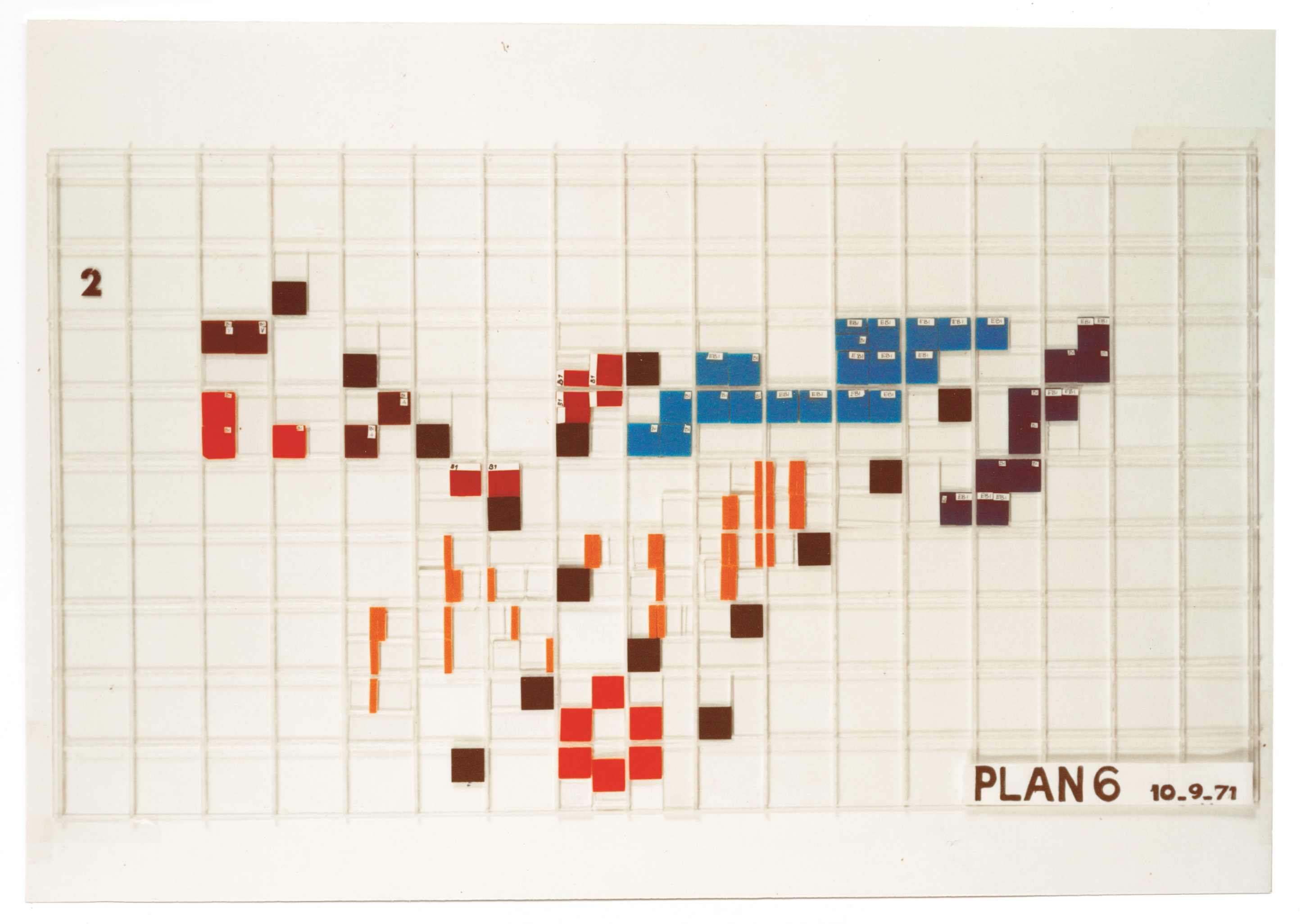

(Source: Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, Architectenbureau Van den Broek en Bakema / Archive (BROX), inv. nr. BROXf1772)

(Source: Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, Architectenbureau Van den Broek en Bakema / Archive (BROX), inv. nr. BROXf1772)

The new freedoms accommodated by the new technologies together with global, inter-state judicial arrangements are experienced as quite ambigious, to say the least. As is well-known these arrangements enable by-passing and undermining state-control through outsourcing and tax evasion. The new social freedoms as designed by the global platforms of Facebook and the like currently meet similar distrust since the platforms have transformed themselves into not only aggregates of private data but also production machines for new private data to be traded as merchandise. So, just as the all-inclusive, public welfare state system of good intentions created its own paranoia, today the ubiquity of the new private technologies of security, ease and comfort paradoxically brings about a constant nervousness without any prospect of relief or relaxation. In the late 1990s, during the first hype around the new possibilities as enabled by internet technologies, some voices already warned for ‘ideological smoothness’ in architecture and planning (Michael Hays, for instance), yet all sorts of neo-Deleuzean concepts – horizontal, rhizomatic, swarm-based – were recycled as to promote a new libertarian freedom away from state control systems. Interestingly enough, Bratton’s concept of the accidental megastructure of the ICT-technologies as a ‘stack’ acknowledges the new vertical hierarchies at play, that are nested within each other as interrelational fields or grids of cloud points.

Visualizations

What might be the specific things to observe and what can we learn when comparing the historical discourse with the developments of today? Especially in relation to architecture and urban planning? ‘Total urbanization’ under redistributive welfare state regimes has moved to the next level of the ‘global city’ (Saskia Sassen) or the ‘endless city’ (Ricky Burdett) of global networks and migration flows, of people, goods, money and information. From the point of architecture and planning it is crucial to note that it is not only an issue of sheer accommodation, but first and foremost of the production of new spaces indeed, a process which feeds off our cities, communities and regions, e.g. the industries of real estate and tourism. Architecture and planning are definitely not in control here, they are sidelined by the new eco-systems that produce their own regimes, flows, fall-out and environments. These eco-systems are not quite as harmonious as the very term might suggest. Eco-systems are entropic systems: while one dies and the other is emergent, they live off each other.

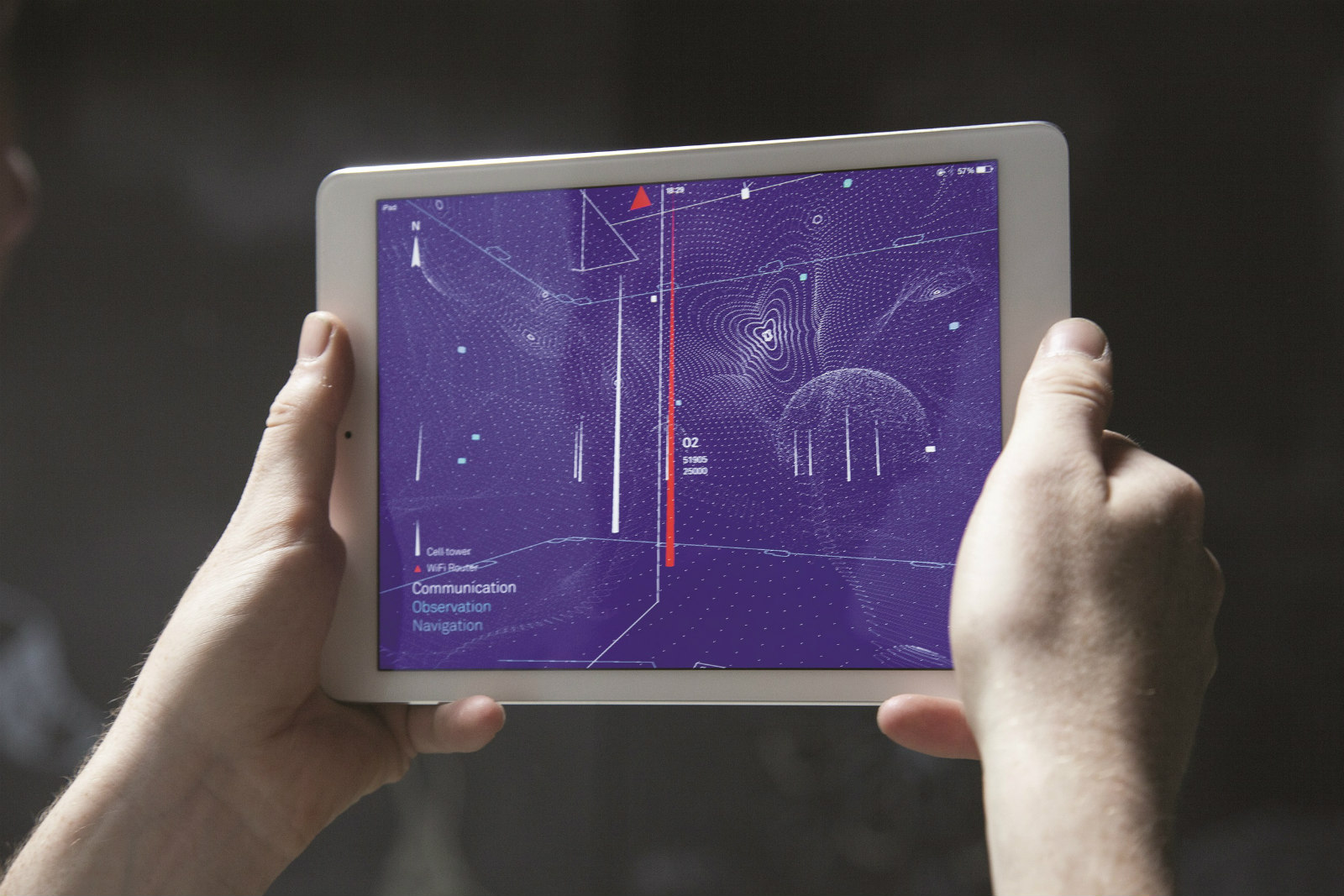

Hence, the emerging new spatial configurations are not just about free interaction, exchange and events through polycentric, labyrinthian networks as so many theorized rather optimistically in the 1950s and 60s (Archigram, Constant, Yona Friedman). Next to the new mobility and interconnectivity, they indeed also create new hierarchies and may sustain enclaves, off-the-grid, et cetera. After all, digital switches also imply the options of switching off and logging out, a condition of disconnection, cloaking devices and opacity, something visual artist Femke Herregraven has coined ‘geographies of avoidance’.

(Photo: Juuke Schoorl)

Unsurprisingly then, a critical role for architecture and urban planning is not so easy to delineate in this ongoing development. As design disciplines they are instrumental in helping to support and bring into the world this ‘accidental megastructure’. Yet, their impact seems to be much more profound on the level of theory and language: architecture and urban planning contribute the models, concepts and metaphors (for instance the one of megastructure), by which it becomes possible to (re)think, visualize and imagine the ubiquitous conglomerate of ICT-infrastructures and their impact. The question of visualizing contemporary ‘totalizing’ regimes of technology and space is most urgent from the point of view of democratic, open societies. Such visualization would enable a reframing of the ‘polis’ and the so-called ‘body politic’, be it a nation, a city or otherwise, as to understand where we are and how to inhabit and traverse the spaces of digital communication.

* The JBSC is a research center, founded by Het Nieuwe Instituut and Delft University of Technology, headed by Dirk van den Heuvel, and based in Rotterdam at Het Nieuwe Instituut.

This insert is part of Volume #50, ‘Beyond Beyond’.

This insert is part of Volume #50, ‘Beyond Beyond’.