In a certain sense, looking at the beyond is something that we cannot do today, other than from the vantage point of a beyond the ‘beyond’. Looking at the connections between progressive political movements and planning/building practices in modernity and their ways of departing into ever new ‘beyonds’, beyond the boundaries of historically given urban and social formations – today, we are certainly beyond these dynamics. And it is not so much postmodernism that needs to be invoked here, but rather two reflections on politics, planning/building related and otherwise, that are bound for the beyond. One reflection concerns how progressive, modernist, avant-garde politics, even at their height, were compromised by, or even complicit in, affinities with paternalistic, top-down governance (Red Vienna) or even with totalitarian rule (fascism). The second reflection, more pertinent to our present moment, concerns the extent to which the dynamics of going beyond have, since the late 1970s, shifted to a regime of (self-)government and accumulation which is addressed and theorized under labels such as neoliberalism, Post-Fordism or new spirit of capitalism.

Today, much of beyond-bound dynamics seem to have been taken over, or at least compromised, by neoliberalism. This especially goes for the willfully planned erosion of frameworks and positionings – e.g., of differentiations between times and places of work and of leisure, or of the possibility of finding large parts of individual and social experience outside of the reach of capitalization. Posing as ‘deregulation’, but really being about administering the enforcement of rule changes to the advantage of capital, neoliberal governmentality has far extended imperatives of expenditure, of going beyond your limits, of becoming flexible in a self-entrepreneurial way. In the context of urban planning, the ever new ‘reaching beyond’ of neoliberal capital has turned cities into playgrounds for investors and has often made innovation synonymous with the gentrification and commercialization of urban spaces.

All this is well known and has often been analyzed. The kind of going beyond this very beyond that I am proposing here comes with a certain seeming disadvantage, which may turn out to be (just) the necessity and also the opportunity to specify my point(s). This is because I advocate operating by strong planning propositions, by positionings or settings (Setzungen) and, yes, by explicit and formally declared regulations in the face of neoliberal hegemony. And the precarious aspect of my approach in planning/building matters, its aspect in need of specification, is this: I advocate positionings that go beyond the beyond – and not a return to what we once had, to any notion of stable grounds, of guarantees etc. In other words, if there are turns to be taken involved in my proposal, they are not returns. The issue is how to distinguish sharply between a ‘return to stable rules’ (which I am critical of) on the one hand, and powerfully (precariously) positioned planning propositions (PPPP) in the context of urban justice on the other.

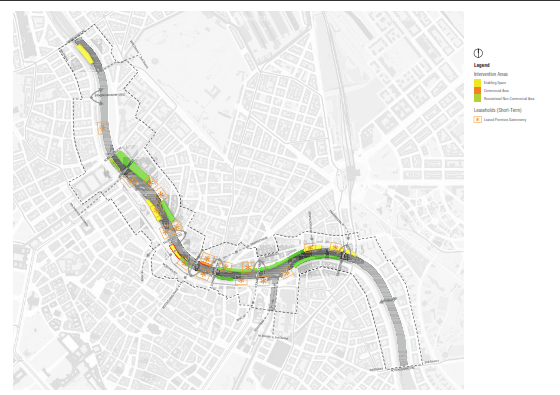

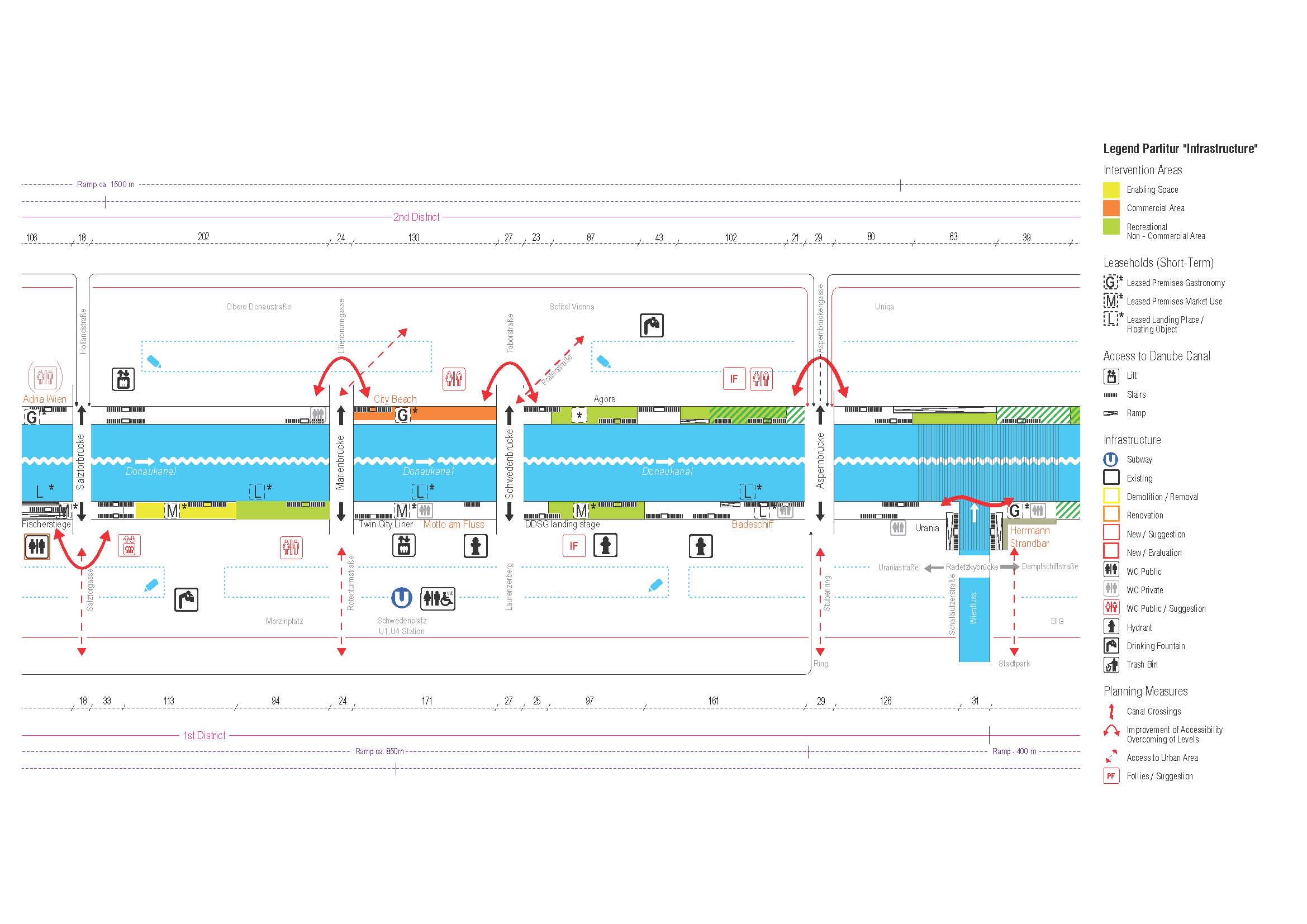

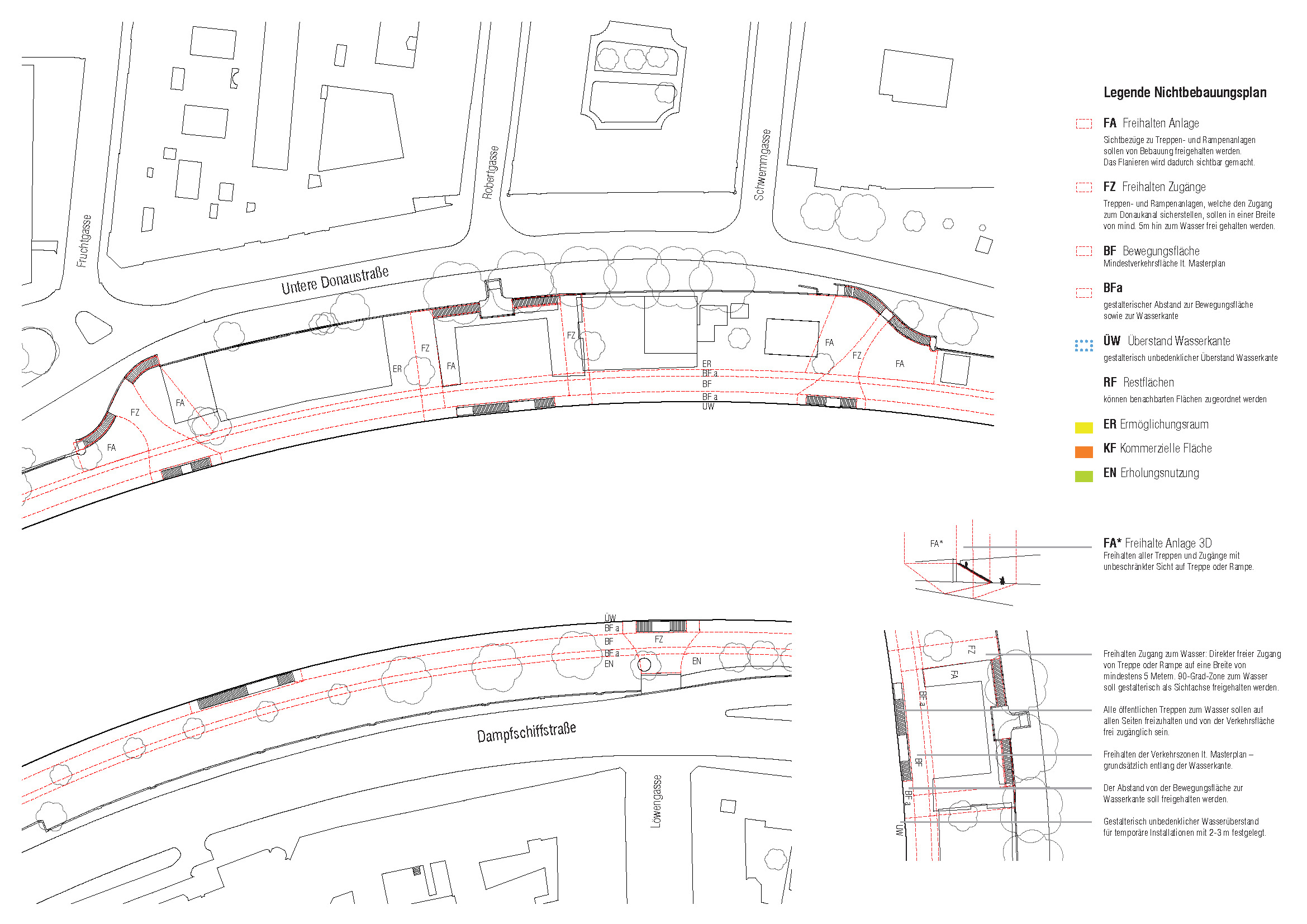

Let me bring up three points here, involving my own practical and theoretical/critical/activist experience as an architect and urban planner based in Vienna. The first answers to the possible objection that PPPP would be a return to centralist state authority. It thus highlights the way in which PPPP seen historically – that is: here and now – act to an overwhelming degree only negatively and in a non-hegemonic way. This is because the appropriations of urban space (and people’s lifetimes) by neoliberalism – and also by increasingly tight security regimes, racist and classist in character, – today act as ruling powers that often go almost unchallenged. PPPP are a way to manifest some dispute and dissensus over the commercialization and policing of cities. And it goes without saying (and yet should be added) that the propositions made through PPPP are subject to criticism, objection and dispute themselves. This is something enabled by their character as explicit positionings – rather than vague sloganeering or guidelines that are flexibly adaptable to investors’ desires whenever and wherever they arise. My understanding of PPPP is about limiting excesses of capitalization and preserving some non-commercial, undefined spaces, especially in centers of cities. The negative (negating) aspect of such a strategy becomes manifest in the example of the non-building plan in which Susan Kraupp and I, commissioned by the city of Vienna, drew up urban development guidelines for Vienna´s Donaukanal, a central channel riverside area that has become a recreational and nightlife hotspot, and is as a profitable place now under strong pressure from ever more investors. The non-building plan for the Viennese Donaukanal is a reaction to the intensified commercialization and quasi-privatization of this centrally located urban riverfront, and it references in graphics and precision the building plan codes. We invented this planning instrument in order to strongly advocate zones of non-building, central urban areas free of commodification.

(Drawing: ARGE Heindl/Kraupp)

(Drawing: ARGE Heindl/Kraupp)

(Drawing: ARGE Heindl/Kraupp)

A second aspect of our Donaukanal non-building plan carries further the necessity to distinguish going beyond the beyond from a mere going back to old authorities. This concerns the problem of how to inherit, how to draw lessons from, the planning and wealth redistribution politics of 1920s and early 1930s social-democratic ‘Red Vienna’. To cut things short: looking back on Red Vienna as an egalitarian political project with intense building and planning activities, one has to confront the paternalistic, disempowering sides of this period of urban governance. In this context it becomes especially salient that our non-building plan, as an instance of PPPP, was not imposed as an administrative regulation tool of city politics. Rather, an eminently political charging of that plan came about when in 2015/16 a grassroots movement of city dwellers tried to protect the last horizontal stretch of grass in the central parts of the Donaukanal open to the public from being ‘developed’ into a large restaurant – and that movement (Donaucanale für alle! – part of the Viennese Right to the City movement) used our non-building plan as a prescription which they politicized by situating it in the staging of a dispute over the right to central urban space. So, rather than working top-down by imposing rules on people, the non-building plan was put into action by moments of self-empowerment that ran bottom-up. Or rather, the way the protests used and reframed our plan was a way of going beyond its technical and administrative character and also its potentially authoritarian character (in fact only potentially, because not everybody in Vienna´s city administration supports a planning tool so unfulfilling of investors’ wishes). And the protesters, going beyond a technical planning measure, thus turning it into PPPP in the first place, limited the going beyond the boundaries of public space by which capital’s private appropriation of cities proceeds and operates.

The third and final point concerns the vexed issue of participation, and this is again an instance of PPPP not wanting to go back to any Golden Age of all-encompassing state or city government authority, nor to any naive concept of ‘ideal conditions of speech’. Rather, a planning strategy that sees itself as democratic, empowering and dissensus-enabling (for facilitating conflicts rather than silencing them is critical of a scenario in which today’s city administrations appear as omnipotent wish-fulfilling agencies: they appear as the ersatz sovereign to be approached by the people with a wish list of fancies and interests relating to planning and development of urban space. This, of course, is a scenario all-too often found in situations labeled with the catch-all phrase ‘participation’, used as a panacea in post-democratic governance. The flipside of this scenario would be a kind of fetishization of individual preferences; a neo-feudal approach to city administrations as Santa Clauses handing out presents to those who behaved well in participation processes, is the flipside to the high esteem in which tastes, whims, and spleens are held in neoliberalism.

This is the point at which our non-building plan chose to not become entangled in the bias of individual wishes regarding certain Donaukanal areas. Rather, we chose to preserve areas for undetermined short-term functions that would allow any usage to take place (i.e., would not end up as private appropriations of space). In this manner, an instance of PPPP went beyond the individual with his or her well-learned readiness to go beyond the limits of the self, the everyday, the urban… – into an opening of spaces that remain open for any anonymous purpose in the future. Such an opening, however, requires a position(ing) at which it is developed.