Architecture doesn’t always play the role of nation-builder. But thanks to TV, architecture is often the site where nation-building takes place. In the great domestication of television-watching following Word War Two, our living rooms have become the main receptor for a TV-led nationalism. Andrés Jaque describes its quintessential case: Italy and Berlusconi’s own development of Milano 2.

Post-war Europe was reconstructed by national TV-urbanisms; RAI’s Milan was its epitome. In January 1954, RAI began broadcasting television programs from Milan, headquartered on Corso Sempione in the center of the city. The building included Studio TV3, which was at the time the biggest television studio in Europe. Its headquarters were re-designed by no less than Giò Ponti. In postwar Italy, television was not watched alone. In 1954, the cost of a TV-set was 250,000 liras – three times the annual wage of a clerk. Very few people could buy televisions. They were in bars, churches, or the living rooms of wealthy families, places turned into trans-familial spaces of interclass enactments, where TV was watched. Control over the television signal was precious, for it brought the power to decide what con-tents and dynamics would shape collective existence. While many consider the 1952 European Coal and Steel Community as the first antecedent of the European Union, the real antecedent was the 1950 union that brought together the European national public TV networks, the EBU. For it was precisely these national TV networks that enabled the social, economic and material reconstruction of postwar Europe; operating within a system where national atoms of unified societies could be organized from the top-down to maximize their power of self-production.

RAI worked hand in hand with the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale, a public holding company that owned many of the main everyday-life-making-industries in Italy – from telephones to highways, food to cars, Alitalia airlines to military weapons. By 1960, eighty per-cent of Italy’s population watched TV, with RAI TV play-ing a unique top-down role in unifying Italian society. For instance, RAI significantly contributed to the standardization of language and helped make Italian universally spoken in Italy’s south. RAI suspended its programs everyday between 7:30 and 8:45pm to synchronize dinner-time across the country. National schedules were coordinated to ensure rest hours for workers and home efficiency in family management. TV delivered a coordinated mass of workers to the nationally centralized industries. In 1957, the production of short movies to advertise industrial products began. The intention of these movies was to narrate, to generic universal publics, the value of industrial products. It signaled the birth of the TV commercial. Inventions like the made-in-Milan Carosello, a TV show composed of accumulated short commercials, instigated a common children’s bedtime. Diverse publics were convened for the unspecialized consumption of generic products. The outcome was not only progress or social coordination, but a sort of TV-hysteria. From 1955 to 1959, Mike Bongiorno hosted Lascia o raddoppia, the most successful Italian TV program ever. In this massively watched quiz show, the cultural knowledge of participants was challenged and rewarded. With prizes reaching 5,120,000 liras and with the Fiat 1400 as a consolation prize, the public celebrated the collective achievement of educational competence week after week. Mike Bongiorno knew how to make participants and audiences feel as if they were exactly the same. Equal citizens: ‘the ordinary Italians’. The unspecialized consumers of generic products felt themselves to be a part of the national industry that manufactured these products, in addition to being the labor force that produced them.

1968

In 1968, it was not only students who protested in Milan, but also immigrant workers, coming from the south of Italy, still attracted by Milan’s economic miracle and the industrial development it brought to Lombardy. They were paid twice the wages as in their hometowns, but due to housing shortages, they saw their living costs quadrupled. Scandals, like the cuts in Gescal, the governmental public fund for workers’ housing, brought the conflict to the streets, where demonstrators demanded more government financing. ‘Guerra per la casa’ (war for the house), was the name given to the protests by Casabella. In issue 344, the magazine exhorted big industry to collaborate in speeding up the provision of dwellings. At L’Espresso, it was Bruno Zevi who advocated the relocation of workers from cities to underdeveloped rural areas, where the land was cheaper. Financing would eventually become available, industry was enrolled and rural areas were urbanized. But it was not for the workers. A new urbanism was about to be born.

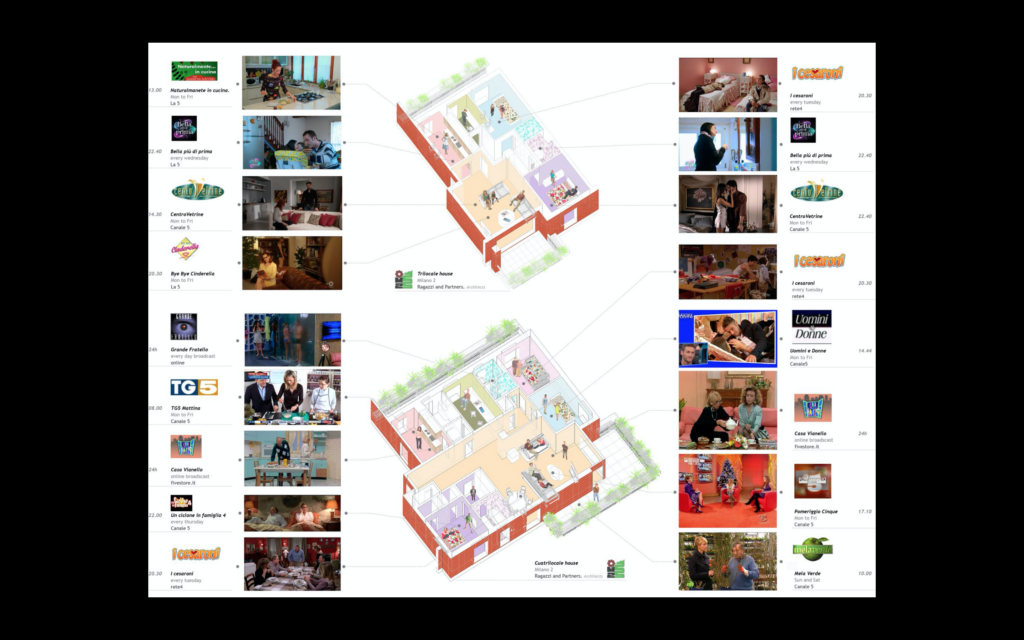

In 1968, Edilnord Centri Residenziali, an urban development company owned by Silvio Berlusconi, started to promote Milano 2, a 712,000 square meter residential city in the municipality of Segrate, a ten-minute drive from the center of Milan on a piece of isolated land that Edilnord acquired at a bargain price due to the noise pollution of air traffic from the nearby Linate International Airport. Berlusconi’s political influence and his association with Luigi Maria Verzé, the founder of what would become the neighboring San Raffaelle Hospital, facilitated the reduction of air traffic and the acceptance by left-wing municipal authorities of his masterplan. Designed not only to supply accommodation for its 10,000 inhabitants but as a complete urbanism equipped to provide education, fitness, entertainment, idealized nature, and, above all, sales. Its 2,600 apartments were placed on the perimeter, their open plan TV-rooms ex-panding into big balconies, not directed toward the Milan skyline, but to an inner landscape with large trees care-fully composed to replace any perception of neighboring human presence – a biological version of TV static. Its section segregated an above-ground domain for daily human life in a green landscape crisscrossed by pedestrian and bicycle circulation from a netherworld of car traffic and underground centralized pipe flows of materials and media content, controlled by Fininvest, the financial holding company owned by Berlusconi.

Milano 2 was the outcome of a growing context of internationally-operated companies in Italy: including Abet, BTicino, Hoval, and Max Meyer. A young globally-oriented design team was led by the then 31-year-old architect Giancarlo Ragazzi, partnered with Giulio Possa, Antonio D’Adamo and the landscape designer Enrico Hoffer. Throughout the media the development was profusely advertised as: ‘La Città dei Numeri Uno’ (The City of the Number Ones). The Number Ones were not the workers, not even the workers who proved to be exceptional. The Number Ones were instead an affluent class of young family-oriented executives. They were not working for the national industries, the ones governed by Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale, but for the growing scene of multinational corporations such as IBM, 3M, Siemens and Unilever who had started to locate their branches in places like Segrate. They were not owners, but they were paid high salaries. They were the number ones in consumption. They had no past, only a future. And they incarnated the shift from a postwar nation-based Europe to a globalized realm of transnational corporations. Berlusconi presented himself as the Robin Hood of the Number Ones, willing to put himself at risk to elevate them to the much-deserved status of property owner. Show-apartments were constructed in the middle of a no-man’s land. Then, they were carefully decorated, photographed, and published in the most fashionable international media outlet: Vogue magazine. Berlusconi insistently explained that he did not have the money to complete the development, but that those who bought early would get an apartment that would double its value as others joined in buying in the future. In the brochures produced to sell the apartments, Berlusconi himself encouraged buyers to “escape from metropolitan chaos”– from traffic, crime, immigrants, and workers. From the city itself. Milano 2 was the architecture that exiled the champions of consumption from urban promiscuity.

Mediaset

More than 5,000 trees were planted at Milano 2. Many of them were already more than twelve meters tall when they were planted, among them fir trees, maples, Japanese red maples, cedar, birches, beeches, gingkoes, magnolias, pine trees, plane trees, and lindens. Arboreal diversity replaced human diversity. In the City of the Number Ones, landscaping replaced politics. If grey concrete and modern architecture had once embodied the aspirations of Milan’s society, it was now a red vernacular which seemed to cater to the emerging Number Ones. With the red vernacular, came pitched roofs, and so, to free the residences from TV aerials, Milano 2 provided an underground cable TV-distribution-network. In 1974, Giacomo Properzj and Alceo Moretti started to broadcast amateur programming through these underground cables. Tele Milano had just been born. Unlicensed movies and amateur self-produced happenings were broadcast from the Jolly Hotel located in Milano 2. The TV station was cheap but successful. It recruited residents to an official board, which then chose the content. In 1975, Berlusconi’s Fininvest became the owner of Tele Milano, and with the 1976 ruling by the Constitutional Court of Italy, authorizing the aerial transmission of private local television channels, Tele Milano became Tele Milano 58 and then Canale 5 and started to be broadcast over the air. By collecting local channels and making them broadcast the same content, Fininvest gave birth to what was, in fact, a private national tele-vision network: Mediaset.

The center of Milano 2 has never been occupied by religious or political power, but by a lago dei cigni, a swan lake, the ultimate architecture of vernacular banality surrounded by the not-at-all banal chained infrastructure of the sport and business center, schools, retail, and Four-Star hotels. A park for the children of the Number Ones to play cowboys and Indians, and spaces where Olympic-style games or treasure hunts were periodically organized. Together it constituted a combined machinery to produce and reproduce the Number Ones as healthy, earnest, aggressive, treasure-seeking, and athletic beings. In performance, these infrastructures are not banal at all. They play a radical role in shaping bodies and societies. Society in Milano 2 is coordinated by some-thing that is not easily visible, namely the underground studios of Mediaset. From the residences, to tune in to your neighbors you need to switch on the TV. Moreover the core of these politics is concealed below the lake, where the main Mediaset studios are located, an under-ground architecture that needs to be hidden to maximize its techno-political conveyance.

In the 80s, Fininvest developed two similar trans-media initiatives. First it acquired the supermarket chain Standa with the intention of seducing the Number Ones, exiled from market promiscuity. It failed. The second initiative began in 1980, when Fininvest created Publitalia. Within ten years, Publitalia would totally transform the urban mediation between production and consumption. Formed to sell advertising space on TV for Mediaset, Publitalia developed a different way to recruit advertisers based on four principles. First, television would no longer be a space for top-down pedagogy, but instead, a device to bring together production and consumption. Second, TV content would be designed according to advertisers’ goals. Third, instead of programming to serve generic audiences, content would be designed to attract specific publics. If toys need to be sold, there will be TV shows for children. If middle-aged males are targeted, there will be late-night shows for them to inhabit. Finally advertisers would not be charged for the amount of time their commercials were broadcasted, but for the increase

in their sales. Robin Hood’s strategy of win-to-win and shared risk was again in play. Small local companies like the furniture manufacturers Aiazzone and Foppa Pedretti, mattress sellers like Permaflex and fur coat sellers like Annabella, unexpectedly grew when advertised by Media-set. Talking of his transmedia urbanisms, Berlusconi stated: “I do not sell spaces, I sell sales”. If nation-driven TV-urbanism constructed space and organized society in social classes, Milano 2 constructed sales and structured society in consumption targets. Considering Fininvest’s stake, it worked. In 1984, Publitalia surpassed Sipra, RAI’s advertising sales unit, in revenue. That very year, Auditel, the Italian research company who measures television ratings and statistics, was created. For the first time, scrutinizing audiences became important.

In 1980, Mike Bongiorno, the historical host of RAI’s biggest hit ever– Lascia o raddoppia – left RAI to become Mediaset’s Number One celebrity. As part of his con-tract, he would get a home in Milano 2 to become part of its community. Milano 2 became the place to go to see celebrities. The superstars would live in penthouses in the Garden Towers, but you could find them playing tennis. To inhabit Mediaset’s Milano 2 implies a life in which the online connects with the offline.

In the underground basement of an ordinary bar in Milano 2, the then number one DJ, Claudio Cecchetto, hosted Chewing Gum, a musical TV show. Week after week, Cecchetto brought dancers to his basement audience from Milan’s disco temple, Divina, where he was resident DJ. Valerio Lazarov, the King of the Zoom-Shot, video-packed the show so it would not only bring the best of Milan’s nightlife into Milano 2’s living rooms, but it would also bring the bodily experience of psychedelia and disco-dancing to the Number Ones. To go out, you had to stay at home.

Mediaset provides a mirrored online home. An implemented version of the show-apartments publicized by Vogue magazine that impelled the Number Ones to buy apartments in Milano 2 in the first place. A mirrored-online-home, that has kitchens, mothers, living rooms, sofas, hosts, bedrooms, showers and older brothers. In order to increase the regulated maximum percentage of promotional space, advertisement leapt from commercials into TV shows, promotional segments devoted to sponsors started to be included in self-produced programs. Progressively, celebrities, mirrored homes, and the outcomes of advertisers’ production started to reconstitute a space to be inhabited.

In March 2012, Clemente Russo, a well-known boxer and policeman, made his début as the main character in the reality show Fratello Maggiore, in which Russo worked to correct the behavior of spoiled teenagers by becoming their fictional older brother. In his Italia 1 show, he can be seen interacting with ordinary people in ordinary domestic interiors where spoiled problematic teenagers are asked to reshape their lives according to his suggestions, a process which is scaled up by the way edited images of his life are scrutinized by 114,113 Facebook followers, many living in Milano 2 apartments, where they switch on the TV, check their smartphones and find him again. There, he wears Dolce & Gabanna and Nike, drinks Bacardi at the Tatanka Club, works out according to Muscles & Fitness magazine, consumes Enervit Sport, communicates with a Samsung smartphone and travels with Alitalia. Roberto Fragalle follows him on Facebook. From time to time, Fragalle publishes photos of himself alternately emulating and distancing himself from the way Russo’s life is portrayed. Fragalle buys and discusses Nike, Bacardi and Enervit Sport. Milano 2’s banality is insistently published on Instagram accounts. Its swans and its trees; the changing seasons of the grass; its living rooms; cats in front of red vernacular pitched roofs; people in front of TV sets.

With more than four million Pay-TV subscribers in Italy, satellite Sky-TV currently doubles the number

of subscribers to Mediaset Premium digital terrestrial television. Both Mediaset Premium and Sky-TV, as trans-national media platforms, are globalizing direct-to-home urbanism, in which the architectural embodiment of the political has been implemented in a way that has so far remained unexplained. Politics in Milan, in Italy, in Europe, in the world, are not happening in squares, cities, or nations. Post-postwar European politics are currently happening in the oddity produced within these transmedia urbanisms.

‘SALES ODDITY: Milano 2 and the Politics of Direct-to-Home TV Urbanism’ is a research project by Andrés Jaque and the architectural agency he directs, Office for Political Innovation.

It is now exhibited at the Venice Biennale as part of Monditalia and it has been awarded with the Silver Lion for the Best Research Project. Research team: Roberto González García, Lubo Dragomirov, Alberto Heras, María Alejandra Sánchez, Ruggero Agnolutto, Enrico Forestieri, Margherita Gioia, Matteo Pace Sargenti, Pietro Pezzani, Anna Tartaglia. Production Team: Paula Currás, Eugenio Fernández, Ana Olmedo, Enrique Ventosa, Miguel de Guzmán, Mari-Carmen Ovejero, Jorge

López Conde, John Wriedt, Giuseppe Tota Ballardini