VOLUME 61. THE INCORRIGIBLE ERNST NEUFERT AND HIS DREAM OF STANDARDIZING YOUR LIFE. ANNA-MARIA MEISTER INTERVIEWED BY STEPHAN PETERMANN

Ernst Neufert’s famed Bauentwurfslehre (BEL in short, in English known as Architect’s Data), ranks among the most influential guides shaping the modern built environment of – at least – the 20st century. Launched in 1936, the book features a unique compilation of useful need-to-know spatial dimensions, technical and organizational standards, and templates for building. With it you could design anything from a dog shed to an airport, or at least have your basics in place. In 2022 its 43rd updated edition was published.

Neufert’s compiling and standardization of building elements notoriously functioned as an enabler for the physical development of the Third Reich, with Neufert himself functioning as a consultant to Albert Speer, the National-Socialist Regime’s chief architect. After the War, Neufert was one of the first professors to be reinstated in West-Germany, then as a professor at TU Darmstadt continuing his efforts providing guidance to architects – during this period his work was an essential element to post-war reconstruction in Germany and far beyond.

Where famed ‘artistic’ architects have long dominated architectural writing, there is a growing consideration for Neufert and, more generally, in the far-reaching consequences of his standardization efforts. Following Walter Prigge’s Ernst Neufert Normierte Baukultur im 20. Jahrhundert (Campus Verlag, 1999), Gernot Weckherlin published BEL: Zur Systematik des Architektonischen Wissens am Beispiel von Ernst Neuferts Bauentwurfslehre in 2017, (Wasmuth, 2017), which critically engages with his work. Enter German architecture historian Anne-Maria Meister. In 2020 she published a compelling research paper in an issue of The British Journal for the History of Science devoted to manuals and handbooks, in which she explored the archive of Neufert, his collaboration with the German Institute for Norms (DIN), and discussed Neufert’s final unfinished work in which he ambitiously tried to transcend from building design teaching towards the design of life itself, or so it seemed.1

This issue [of Volume] tries to establish the grounds for new thinking on guides, handbooks, or manuals. Historically they have offered space as a piece of coming together, of trying to agree on a shared conception of a specific element of life. They are key in design, but also key in addressing the pressing issues we face. For our current moment It seems more than ever a reinvention of Neufert is needed. Sustainable or circular production in our building culture, will inevitably rely on the interoperability of different building systems which demands increased coordination, registration, and maintenance. There is a clear need for a radically new Bauentwurfslehre, one that would probably need to be as daunting as the invention of industrial production, that formed the base for Neufert’s professional life. In conversation with Meister we explore the success of Neufert, and sketch the contours of what a future Neufert should do.

What drove you to Neufert’s archive in the first place?

I have been trained in Germany as an architect and ‘used’ Neufert, or as we all call it, the Bauentwurfslehre [building design theory]. After my studies I started working in an office in Germany, but I realized when I moved to the US in 2008 how differently architectural practice was organized there, both in conceptual framing, but also in pragmatic terms. During my time in the US I shifted from being a practicing architect to being a historian and theorist during my master’s degree at Columbia University. This shift prompted me to start looking into the DNA of norm sheets, reference manuals, and into other, let’s say, very German ‘normalities’. Much of these processes and documents seemed unexceptional when I was in Germany, but the contrast of being in the international context of the PhD program at Princeton (which I joined after my time at Columbia University) opened up the fascinating consideration of the bureaucratic and the obsession with ‘order’ as object of research to me. So, all the German clichés in architecture became my scholarly focus.

How was this received in Princeton? Was this a topic that they also thought was relevant to discuss?

Everybody was very excited, and very interested in this German strangeness. It was when I came back to Germany and started to do my research there that I had to explain the angle and relevance to people. As it was considered to be just so normal in Germany, some of the people I spoke to couldn’t understand what I was looking for. But there has been a trend in architecture history in the last 10 years to look into bureaucratic systems, so my interests now have a good home in both places.

It’s something we also tried to address in Elements of Architecture (Taschen, 2018) and at the Venice Biennale in 2014. We wrote about wheelchair ramp activist Timothy Nugent who managed to get wheelchair ramp access into building code books in the US and beyond. We tried to promote him and others to be at least as relevant as Le Corbusier or Mies, as these rules have become ubiquitous in any building practice in the world.

One of the issues lingering in both architecture history and the understanding of the architect is that before the shift of the field that I mentioned above, historians fell into the same rhetoric, just like many of the architects did, namely to consider regulations and standards (or norms, as I translate them) to be merely pragmatic or technological, separating them from aesthetic or artistic intention. But more and more we realize that the separation never existed, because form is given intentionally also to norms and rules, as the ever more intense research into these connections shows.

How did you start this research?

I was trying to look at things that I had perceived as normal, and try to treat them as intentionally designed or as the result of an aesthetic intention. One might say that I tried reversing the Neufert’s intentions and that of other protagonists, for example the influential German DIN institute or others in that field who try to shape the world using standards. This is what DIN explicitly set out to do after WWI. I take them by their word, and then focus on the spatial and artistic consequences and intentions through the sheets, systems and standards they produced. The more bureaucratically they acted, the more interesting they became to me.

What was the secret of Neufert’s success? How did he manage to build normality?

Neufert was not the first to make the kinds of drawings of dimensions and people he became famous for. On that level there is no ‘innovation’ with Neufert, but he was very good at establishing his brand. Before his BEL came out, construction manuals existed, or the DIN catalog of standards and norms – all things that focused more on how to build things. The (then still published) Handbuch der Architektur on the other hand was an unwieldy multi-volume style and typology collection. Neufert’s primary focus is on the step before construction: designing and dimensions. Another element to his success was that he collected his drawing in a single volume. Rather than the subscription model of the DIN Institute where the need to continuously pay and sort the new sheets into the folder system, the BEL just offered everything from norm to floorplan to measure of men in one volume. And yet another reason for its success was that Neufert really made this his book, despite the many collaborators, students and colleagues, that were instrumental to its conception and form. Neufert, in his attempts to take sole authorship, got into fights and as one son of a former colleague told me, allegedly threatened to kill people over it. He really did not share credit willingly. So, that was one way to success, the old-fashioned way of just claiming fame and credit.

…or being an egomaniac…

…or at least proverbially killing your competitors.

In Neufert’s archive, is there reference to the goal or ambition that Neufert had?

He had certain goals for the book and they were usually formulated as fairly pragmatic, directed at aiding architects in their design work. From my work on his diaries I also came across his ambition time and time again, not unusual for a man of his time; to find a total or universal order for design, and then making sure that everybody uses that. Especially about his measure system, about which he was extremely obsessive, always trying to prove others wrong, such as his competitor Martin Mittag, who had developed an additive system of several smaller modules which would add up to a larger system. Neufert came from the opposite end; he developed an overall order, and then broke that down into smaller measures. He was adamant that that was the better way of dealing with measures in architecture (and not just architecture). His ambition was to find the right system and then stick with it across scales, objects, and subjects. And the irony is that in his diary, you see that he is constantly looking for such a system for his own life, and he’s struggling immensely. So there’s a constant search for total order, both professionally and privately. In his so-called “Selbsteinrede” entries there are many notes in which he repeatedly promises himself how he would improve his work habits, wake up earlier, take notes better, and such…

It has all the ingredients of a dramatic novel or even a Russell Crowe movie…

I wouldn’t want to psychologize a person from just archival papers, but what really struck me in the diary is that it was not a book that he kept writing, but an index card system. It comprised a collection of DIN A4 papers folded twice to fit as DIN A6 index cards into this cardboard box, sorted with dividers in between, using different labels. Not chronological, but a system that related work and private diary entries about himself in the attempt to index his own life. He also self-edited: he often later added comments to existing cards, noting a new additional date, often using a different pen, so you can tell which historical or biographical layer is which. Sometimes he also relabels entries over time, sorting them into different categories, for example from “Selbsteinrede” to “Lebensgestaltung”. I think that speaks to his ambition we talked about before. This constant attempt of getting it right and overlay the system with improvements.

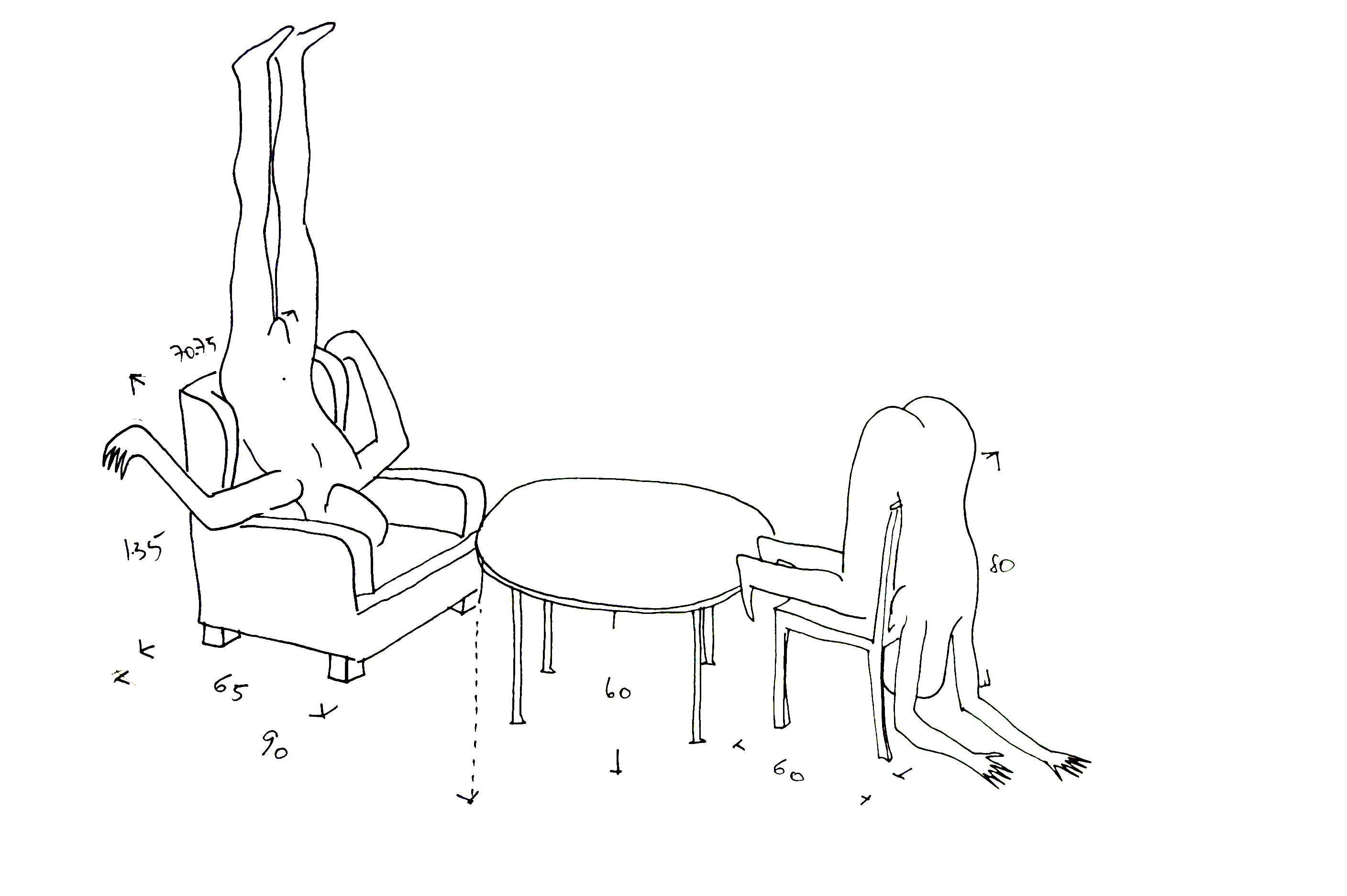

About improvements: when we were writing Elements of Architecture we wanted to have a part which looks at the changes in Neufert over time, specifically concerning the human body. We were expecting that since the average size of the human body changes, our weights and height increasing and such, Neufert would also reflect this, but we didn’t really find them. There are some activities that changed: the early editions feature a dimensioned man carrying buckets of milk, who is replaced overtime by a man smoking in an armchair. That’s the most significant change we found…

In Neufert’s mind the system is based on an ideal which you never have to change. Once you have a measure system, and you have certain increments (for Neufert that’s around 12.5 centimeters), you never question it again. You can divide that further and even go 1.25 centimeters if you want, but there was a certain minimal module he had. And once you fit a male human body into a certain measure then you don’t have much wiggle room to adjust without challenging the entire system. There are sometimes changes he incorporated into new editions when for instance the official norm gets updated or new design elements are introduced. Dog shelters that were in there from the beginning are still in, but Zeppelin hangars are not, as they are arguably no longer considered a relevant design task for an architect. By looking just at the index over time, you get a different kind of architecture history. It offers a codified insight to how the profession changes, but the measures themselves are treated as very stable.

What triggered me in your article on Neufert were the labels in the dairy concerning Lebensgestaltungslehre – one of the many nebulous and hard to translate German words, which I guess would translate to life form giving treatise in English. It’s an unfinished publication by Neufert on which he worked throughout his career. What did this third Neufert-Lehre encompass?

We have some archival material on the development of the other books he made, but for the Lebensgestaltungslehre the material is less clear as it never manifested as a publication. He envisioned it as an all-encompassing way to shape your life in spaces that were ordered, measured and designed. To my knowledge he only wrote about it in his diary, where there was a specific section and abbreviation for the category devoted to it. There are entries in there that had to do with structuring the day, or how to conduct yourself in your life. It would include things like when to get up, how long to sleep, how much work time one would plan before a taking break and such. It’s a diffuse category: it also contains musings on how Neufert would live in a model farm in the countryside after the war. There are also the entries about his daily rhythm, where he keeps telling himself to get up earlier and work more, as I have mentioned above. There is one entry where he links the Lebensgestaltungslehre entries directly to writing books: he tries to figure out how long it will take him to write this new Lehre. He envisions a certain number of pages and he uses a calculation of the time he had spent on the first book and its page count to predict how long it would take to finish the Lebensgestaltunglehre. While the entry was made in the early 1940s, it has an update from Neufert in 1980 which disappointedly says: “not much progress.”

It sounds almost like those irritating Google Assistant attempts which try to give you tips and advice on how to plan your day. How to become indeed more efficient, but even then in more totalitarian form?

It’s the ultimate attempt to order life for himself – and ultimately everyone. To the question your issue raises, about the need [for] future manuals, I think one might need to change the question to: Who is writing the manual? Or perhaps, what kind of order or systematization is wanted? Why, and by whom? And with what intention? By asking these questions, you already get a different approach to what one might do now, which would need to be, I would say, much more collaborative or participatory. Is it a manual for teaching? Or is it for normalizing certain elements, which are difficult to avoid otherwise? In any case the questions would need to change, and by that the method and outcome would change considerably, as well. The total system imposed from above tried to prevent questions, while we now must raise more and more of them.

The Vitruvian man central to Neufert’s work is very problematic and essential at the same time in his norm system. From the medical world, and more recently the design world too, we know how white male dominance has negatively affected other groups. So this suggests we have to be dynamic in defining what humans are, and dispose of an idealized figure at all. At the same time we need agreements in measurements i.e. if we want to take for example reusing materials more seriously. We have to adapt to standardized elements in order to maintain future use compatibility. Neufert took that into the egomaniac, but maybe we can explore alternatives?

One thing to counter that would be to focus on methods. Methods are not unproblematic in themselves, as they also suffer from bias, but a multiplicity of both models and methods is key. Hence any wish for a “new manual” would need to consider instead multiple guides. The singularity of having the manual for anything, regardless of what it is, is an inherent problem of the genre – even if it is toward more openness. The EU directive in which all phones have certain kinds of plugs and cables demands that Apple, for example, can’t have a proprietary connection is a democratizing function against private investors or corporations unifying or streamlining efforts toward market dominance. Yet, this still carries the baggage of how to find the one solution that becomes the ‘new standard’. Heterogeneity can create all sorts of problems and minimize compatibility, lifecycle duration, and sustainability impacts and such; but more diversity is urgently needed to include and open multiple perspectives and voices. In both cases I think it’s very important to always be suspicious of what is not being said when pushing for a new standard.

There is always this daunting prospect within standardization that we will all live in the same shoe box, with the same interior, eat the same food, etc. For our future guide this is probably one of the key things to evaluate or test. Looking back at Neufert I am inspired by his success in connecting information and building something that is quite new that is useful for many architects at the same time.

The other question with the manual is of course: who you [think you] need to instruct? I mean, there could be an architectural manual that’s not for architects, but for users, which then can instruct them how to question the architect about design. I mean, there can be subversive ways of making a manual that are not top down but emancipatory and empowering.

What is it that you take for your research for a next generation of designers? Questioning these norms, but also offer fuel for developing alternative systems?

Mostly I try to instill in my students a clear sense of suspicion that anything that is presented as ‘normal’ to them has a history, and often implies an intention, an agenda, or aesthetic ambition, even if that’s not overtly reflected. So, if they are asked for example to follow a design process which moves from the large scale towards the small, I try to challenge this assumption about a normalized design process, and encourage them to turn that around and start with the detail and then develop a whole city out of that. My goal is to instill an awareness towards questioning the very unassuming, or things you don’t even really notice.

Could this be something the new European Bauhaus could address?

I am not fully aware of what is happening there. There are interesting people that might, hopefully, give this project the right spin, i.e. people like Maarten Gielen of ROTOR. But, as this conversations shows, I am skeptical towards any large-scale attempt at a unified solution or unified response to something – even, or rather, especially, architecture education and spatial awareness.

Maybe that is another subplot in our Russel Crowe movie? Yourself as the subversive element trying to sabotage standardization itself, like the Trojan horse in the normalized world? Thank you for this conversation!

Meister, A. (2020). Ernst Neufert’s ‘Lebensgestaltungslehre’: Formatting life beyond the built. BJHS Themes, 5, 167-185. doi:10.1017/bjt.2020.13 She is currently completing a book manuscript on Standardization as “Paper Architecture” in Germany in the first half of the 20th century, where Neufert and the DIN Institute also feature largely.