2015 marks Volume’s 10th birthday. The coming weeks we’ll republish our readers’ favorite articles. If you feel tempted to highlight yours with a brief motivation, please send an email to 10years@archis.org.

“Why this article? It symbolizes one of the most genuine values of Volume: to show the forces that shape our world and habitat with and without the conscience intervention of professional designers and planners; to reveal how things are made; and, to claim the utility of architectural intelligence as a mode of thought, as a splendid tool not only to operate in the world but also to explain a state of things (which in a world where fictions permanently leverage facts, is not so far from acting in the world). In addition, ‘Radical Interiority’ is a masterful piece of storytelling. It is smart, taut, engaging and propulsive… The author takes her time to set the drama in the background of architecture, keeping you longing for more until it ends – only to let you know that this is hardly the beginning. As if it were a chapter of your favorite TV series, the article has a wise script. Effortless to read, its lure is sophisticatedly designed, echoing the kernel of the research: placing seduction and desire at the core of the dynamic and reflective relation between popular culture, lifestyles, media, design and architectural culture.”

“I also pick ‘Radical Interiority’ because it is conceived of not only for architects to read. It proves that architecture can be likeable for other people and for other reasons than those regularly advocated. But what ultimately makes me select this work is how it makes you consider what it does not say. Like Jaque’s ‘Sales Oddity’, ‘Radical Interiority’ is all about what is implicit – uncovering architecture’s flirt with media and consumption as a potential opening to enter the body politic. In other words, it reveals an access to affective politics, testing the reliability of our beliefs and opening new fields of concern for both research and practice. However, here is a warning before you start reading: if you want to make the most of it, you’ll have to attack the full insert (and hopefully devour the whole Interiors issue)!”

Paula V. Álvarez is an architect based in Seville (Spain), founder of the editorial practice Vibok Works. Her work brings together research, editing and writing from an experimental perspective. She teaches Editorial Communication at the School of Architecture in the Polytechnic University of Madrid. She is a regular collaborator in research, cultural and educational projects by architectural institutions like Arquia Foundation or Mies van der Rohe Foundation. She is currently working in her PhD on ‘Editing as Cognitive and Operative tool for Architecture at the turn of the 21 century’.

The warning comes early, in the editorial of the very first issue of Playboy magazine with Marilyn Monroe on the cover and the promise of her naked body inside: “We don’t mind telling you in advance – we plan on spending most of our time inside. We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph, and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”1

The playboy man is an indoors man. But why “we don’t mind”? Why would they mind? What’s there to mind? The editorial is clear. Other magazines for men “spend all their time out-of-doors – thrashing through thorny thickets or splashing about in fast flowing streams.” The playboy is a different kind of animal. He is also a hunter but the metropolitan apartment is his natural habitat. He knows everything about it and keeps adjusting it to better catch his prey. In fact, he cares more about the lure than the catch. It is the apartment itself that is the ultimate object of desire. The playboy and his magazine are all about architecture.

This philosophy is embodied in the figure of Hefner himself, who famously almost never left his bed, let alone his house. He literally moved his office to his bed in 1960 when he moved into the Playboy Mansion on 1340 North State Parkway, Chicago, turning it into the epicenter of a global empire and his silk pajamas and dressing gown into his business attire. “I don’t go out of the house at all!!!… I am a contemporary recluse”, he told Tom Wolfe, guessing that the last time he was out had been three and a half months before and that in the last two years he had been out of the house only nine times.2 Fascinated, Wolfe described him as “the tender-tympani green heart of an artichoke”.3 Even when Hefner went out, he was not really out, but wrapped in a succession of bubbles, all designed to extend his interior: the specially outfitted vehicles; the Big Bunny jet, a stretched DC9 designed by Ron Dirsmith, the architect of the mansion, with a gourmet kitchen, a dancing floor, a living room/conference space, discotheque, a wet bar, state-of-the-art cinemascope projectors, sleeping quarters for sixteen guests, and Hefner’s suite with shower and an elliptical bed covered with Tasmanian opossum skins; the home away from home of the Playboy clubs, starting with the Chicago club in 1960 and rapidly growing from seven Playboy clubs in 1963 to seventeen by 1965 and ultimately thirty-three around the world. Playboy is produced in a radical interior and is devoted to the interior, devoted like a lover.

The magazine was filled with interiors from the very first issue. No detail of domestic space is left untouched, from the furniture, lighting, hifi, and dress code, to the mixing of a good martini. The first page of the first issue of the magazine, facing the editorial, shows a cartoon of the proud playboy (a male bunny) at home in his pajamas and bathrobe, standing beside his modern furniture, high lighting the Hardoy Butterfly chair of 1940, which became a signature piece in the playboy interior, often acting as a kind of portable home for the Playmate. Already in the second issue, a feature on naked playmates keeps describing in detail the ‘modern’ design, flooring, and furnishings of the California ranchstyle house where the models are photographed. “Some say you can judge a man by the way he furnishes his home”, the article symptomatically begins, in what will become a kind of mantra in the magazine.4 Design is the key to the Playboy lifestyle. Frank Lloyd Wright and Wallace Harrison are praised in the fourth issue for bringing modern design to the house and the skyscraper. “The exciting simplicity of modern architecture” stimulates Playboy.

The role of design for Playboy becomes even clearer when the next issue provides a guide to the twenty-five steps of a successful conquest. The sequence is mapped in a modern apartment as if the layout and equipment itself choreograph the dance of seduction. As the playboy maneuvers his prey towards the bed, each detail of the apartment assists the movement. Not by chance does the journey begin with the lightweight curves of the butterfly chair and the deep sensuous folds of Eero Saarinen’s 1946 Womb chair, another signature chair of Playboy. It is as if the designers are in the room, helping out. The Playboy apartment is a cocktail of modern design, martinis, and music. Far from simply providing an array of seductive images, Playboy analyzes the architecture of seduction. It offers a kind of user’s manual to the reader. And in the end, the sophisticated playboy needs to know more about modern design than about women.

Everything is seen through the lens of design. Even a spoof on psychoanalysis offers a detailed drawing of the couch and plan of the room. Likewise, the movement of furniture is broken down, as are the precise movements of the martini production. Playboy relentlessly dissects each dimension of the interior.

This dedication to the perfected interior culminates in September 1956 with the Playboy Penthouse – the first Playboy designed apartment lavishly illustrated in an eight page spread, longer than any typical feature, and continued with another six pages in the following issue. Rejecting the convention in which “the overwhelming percentage of homes is furnished by women”,5 the point was to create an interior that is unambiguously masculine, with equipment that stays and women that come and go: “A man yearns for quarters of his own. More than a place to hang his hat, a man dreams of his own domain, a place that is exclusively his. PLAYBOY has designed, planned and decorated, from the floor up, a penthouse apartment for the urban bachelor.”

Atmospheric renderings conjure up a continuous landscape of entertainment. Each successive space is described in great detail with all the individual items separately identified, including designer, manufacturer, and price: Knoll cabinets, Eames and Saarinen chairs, Noguchi table, etc. The house is full of the latest electronics and media. A signature feature is the electronic entertainment center with hifi, FM radio, TV, tape recorder, movie and slide projectors. The entire environment can be controlled from the bed which is the epicenter of this idealized interior. The imagined occupant/driver of the space is the reader. In a canny seduction, the magazine describes the most advanced interior architecture design for “a man perhaps very much like you”. The reader, or the reader’s fantasy, is the client and is offered the keys to the apartment in the first page of the article.

Architecture turned out to be more seductive than the playmates. The penthouse feature was the most popular in the magazine’s history, surpassing even the centerfolds.7 Architecture became the ultimate playmate, the only one allowed to stay. Playboy received hundreds of letters requesting more information on the house, asking for more detailed plans and where to buy the furniture. In response, the magazine started a hugely popular series of features on ‘playboy pads’, including the Weekend Hideaway (1959), the Playboy Town House (1962), the Playboy Patio Terrace (1963), the Playboy Duplex Penthouse (1970), and so on. In each case, the fantasy is the same: the bachelor and his equipment are able to control every aspect of the interior environment to choreograph the successful conquest and subsequent erasure of all traces in preparation for the next capture.

Playboy architecture ultimately turns on the bed, which becomes increasingly sophisticated, outfitted with all sort of entertainment and communication devices as a kind of control room. The magazine devoted a number of articles to the design of the perfect bed. Once again, Hefner acted as the model with his famous round bed introduced as a feature in the Playboy Townhouse of 1962, originally commissioned to be his own house, then installed in the Playboy Mansion. Not by chance, the only piece of the Townhouse design to be realized was the bed. The bed itself is a house. Its rotating and vibrating structure is packed with a small fridge, hifi, telephone, filling cabinets, bar, microphone, Dictaphone, videocameras, headphones, TV, breakfast table, work surfaces, control for all the lighting fixtures, etc. for the man who never wants to leave. The bed was literally Hefner’s office, his place of business, where he conducted interviews, made his phone calls, selected images, adjusted layouts, edited texts, ate, drank and consulted with playmates. If Playboy is all about architecture, this architecture is an extension of the bed. The playboy interior is finally all bed.

Playboy made it acceptable for men to be interested in modern architecture and design. Readers were encouraged to think they could have a piece of the idealized interior in their own lives. A cycle of desire was built up as Playboy kept feeding the fantasy with more and more detail about the objects. And these desired objects were by the most sophisticated designers of the day: Georges Nelson, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames, Eero Saarinen, Roberto Matta, Archizoom, Jo Colombo, Frank Gehry, etc. Eventually the playboy architecture caught up with the furniture. The somewhat generic rectangular mid century modernism of the playboy designed pads gave way to more extreme concepts as the magazine started to appropriate already existing houses as ‘Playboy Pads’. The playful geometry of realized houses such as Charles Moore’s New Haven Haven (published in Playboy in 1969), Matti Suuronen’s Futuro house (1970), John Lautner’s Elrod House (1971), the Bubble House of Chrysalis (1972), and the House of the Century by Ant Farm (1973) became the model of seduction through design. It is no longer one or two curvy designer chairs that prop up the ‘comely’ girls next door at the heart of Playboy’s core fantasy but fully realized buildings and interiors by leading experimental architects that are shown filled with women that seem to become more sophisticated along with the architecture, as if design intensifies and elevates the fantasy.

Some high profile architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Buckminster Fuller were the subject of features and interviews in the magazine as major cultural figures, perfectly dressed, and sympto matically celebrated for their masculine sophistication, with subtle hints that they too are playboys. In the very first year, Wright was already praised as an “uncommon man”, who “zooms” around in his Jaguar, with a controversial love life and “radical, exciting” buildings. The architect becomes a model, carefully posed at the very heart of the playboy fantasy. It is as if the architect’s dreams of the future get fused with the dream of sexual conquest.

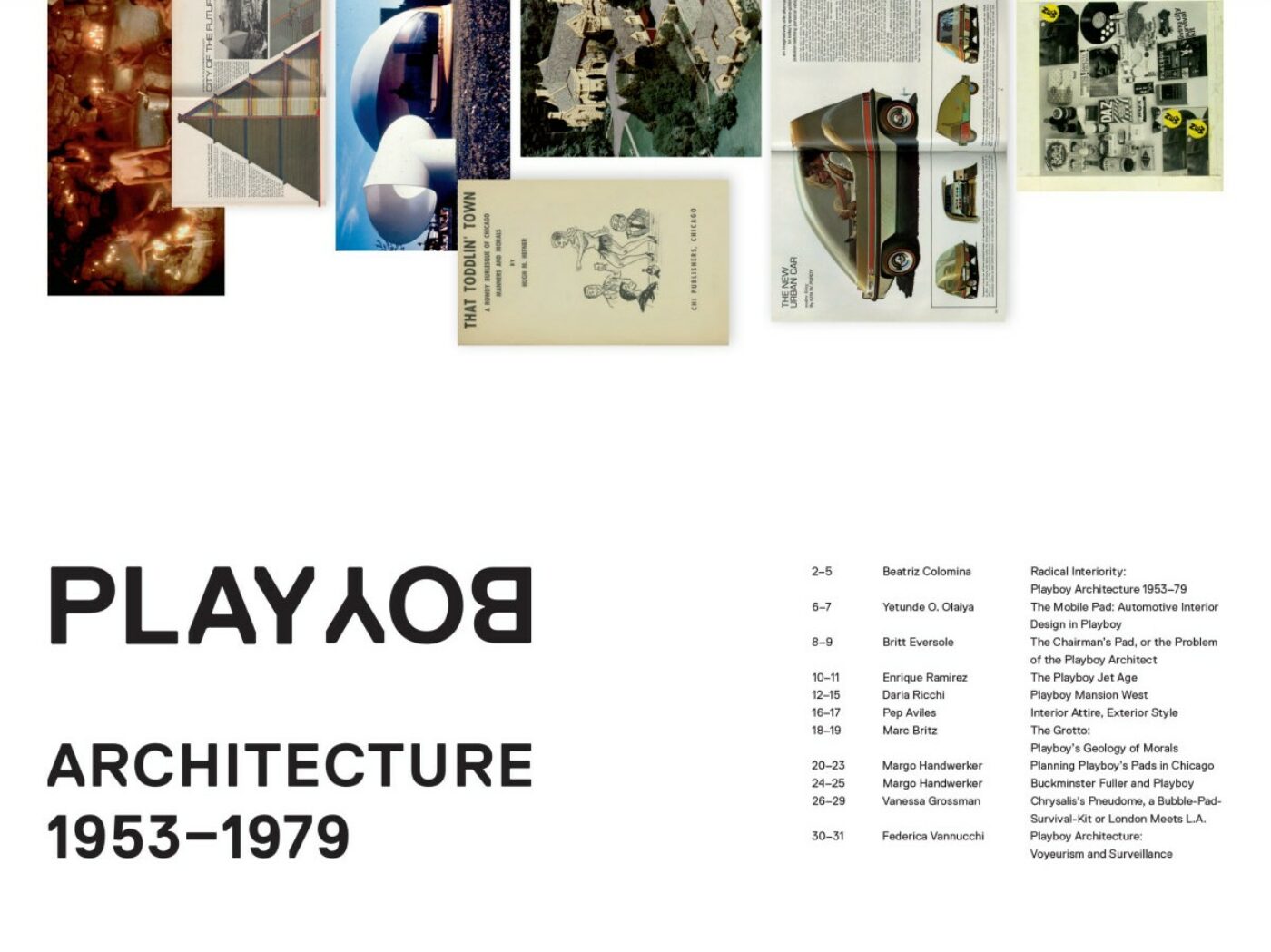

Not by chance does the magazine present the vast floating megastructures of Fuller’s ‘City of the Future’, Paolo Soleri’s ‘CathedralCities for a New Society’, and Moshe Safdie’s ‘Habitat’, built for Expo 67 in Montreal as a fragment of a possible future city. Thousands of independent apartment units are stacked up into vast science fiction forms. The architect stands at the edge of the future, visualizing the possible trajectory of design. The playboy never goes outside but dreams of flying towards the future in his sealed domestic capsule. The playboy interior finally swallows everything, even its own future.

In the end, this continuously expanded world of design is itself a sexual fantasy, a space the reader is skillfully seduced into. The more detailed the description, the more intensely the reader desires to get in. To subscribe to Playboy is to get a set of keys to a dreamlike world, a magical interior. With its massive global circulation and sexualization of architecture, Playboy arguably had more influence on the dissemination of modern design than professional magazines, interiors magazines, and even institutions like the Museum of Modern Art. Design was not simply featured in the magazine but was its very mechanism. And of course designers were readers too. If Playboy couldn’t exist without architecture, it seems as if architecture culture couldn’t do without Playboy. The magazine deeply affected the imagination of critics and architects. Reyner Banham’s 1960 slogan “I’d Crawl a mile for Playboy” captured the sentiment of a whole generation. Almost every male architect was reading Playboy and it insinuated itself into the fantasies of the field in ways that need to be explored, analyzed and critiqued. A small taste of this ongoing research project is offered here on the occasion of its exhibition in the NAIM//Bureau Europa in Maastricht.

References

1. Playboy, n. 1, December 1953, p. 3.

2. Tom Wolfe, ‘King of the Status Dropouts’, The Pump House Gang (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1965).

3. Ibid. p.63.

4. ‘At Home with Dienes’, Playboy, n. 2, January 1954.

5. Playboy, October 1956, p. 65.

6. Playboy, September 1956, p. 54.

7. Gretchen Edgren, The Playboy Book (Taschen, 2005), p. 38.