Ahead of the upcoming release of V49, Volume presents several articles straight from our archives to stimulate a renewed discussion on the themes contained in the new issue.

Connection is a popular motif in design: all types of infrastructure – bridges, pathways, transportation, service systems and applications – wish to tie into the urban fabric to make things productive. However, there is also an opposite tendency: the act of disconnection. Amelia Borg and Timothy Moore ponder how one can physically remove themselves from the communication of things.

‘London Lovin’ it April 12-25

I noticed on a social networking site that an online friend was traveling to London. We had met on a geolocative app and since then we have befriended each other across various platforms. Although our relationship was relatively new, by waking up and checking status feeds, following geo-tagging, and conversing via webcam, scrabble or viber, we felt like old friends. It was Easter, the Eurostar ticket was on special, and with some time off my Amsterdam job, I decided to surprise my friend in London. But there was one, big problem. He knows my every move; he certainly knows something is up when my distance from him shifts from 554 to 10 km. Would I have to turn off some of my location services on my smart phone? A few days later, as the train surfaced from the darkness of the London underground (where no wifi can penetrate) into the crisp St. Pancras interior, a message flashed up, caught in the reflection of the train window: “Are you in London?” “If only I had a master disconnect button!”, I wryly thought while typing a swift response. The internet of things operates on the premise that we all stand connected in an entangled, continuous interchange of wires, pulses and connections. We connect to open data, we connect with our peers, we connect to the fridge, we just connect. We also, like, check-in, -out, bump, swipe and send. It is a world of the intransitive verb, an actor and action without object because everything is subject. Everything is a link in the communication exchange. The drive toward a state of collectedness is innately human. We have an unabashed tribalist urge to be together: we like to run with a pack and this is evident in the number of geo-tagging applications. Add in the recent synergies between nanotechnology, wireless sensor networks, actuators, and identification devices and there is an increasing complexity that is difficult to fathom. Our devices are connected all the time via the encrypting shorthand of RFID, NFC or Zingbee and Blue Tooth. And as these devices become ever more ubiquitous and intelligent, it increases the likelihood that we will lose control of this dataflow. We are monitored by social networks, sold out by Apple, and spied on by Google street view. Our RFID information is tracked and hacked, our consumer habits data-mined. For every big brother story of a society secretly surveilled by manipulative corporations, there are elements of digital data collection that have also resulted in major benefits. What we wish to posit, however, is that while in the past we had to overcome poor telephone wiring or LAN dial-up to connect, today the problem is the opposite. Being so well connected (in the Western world) prompts an ‘other’ impulse: to switch off – to disconnect, disengage, disassociate. This ‘dis’, a Latin prefix is a negative, a reversing force materialized in a removal or release. The importance of disconnection is not just a question of privacy; being able to disconnect is pivotal to the reflection and consequent reinvigoration with the world around us for the quick fix of connected togetherness is no guarantee of some sort of heightened and immediate solidarity. When we sit down with our housemates on a Sunday night, we may share the room but we may not even talk to each other. And even when we do talk our digital selves are harvesting a surfeit of data online. Thus it is the ability and right to pas de deux between these two states of being, on/off, and the gradient that falls in between that will ensure the Internet of Things as an emancipatory tool for the individual today. Consequently we wonder: can architecture provide disconnect and distance?

Filter

Almost half a century ago the dichotomy of on/off had particular resonance with the paper architecture of the time – Price, Archigram, Constant, Friedman – who envisioned an environment in which the individual could be liberated by technology. In particular, the metabolism movement in Japan proposed a technological architecture that was flexible and expandable on a citywide scale while synchronically overlaid on the existing city. Metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa speaks of this place as the ‘meta-polis’; it is the city beyond the city. And within these megastructures there was a place for the individual to disconnect. In his ‘Capsule Declaration’ of 1969 Kurokawa calls for the provision of capsules to allow for this solitude, each capsule being a space that guarantees individual privacy. With the retreat of the individual into the capsule, the capsule serves as an outside extension of the (cyborg) individual. Architecture mediates as a buffer. He writes, a capsule ‘permits us to reject undesired information’ and allows one to ‘shelter from information they do not want, thereby allowing an individual to recover his subjectivity and independence’. This independence is demonstrated by the typology itself that would circumvent traditional social structures in which a family unit would be determined by the number of capsules docked together. This avoided a hierarchical thinking, because both the building and social system could disconnect and dissolve. He also saw the architecture of the capsule as an organizational tool, an interface to perform complex tasks beyond human capabilities: from the mundane to be coming a mobile craft that travels to the seaside on weekends. While the capsule underpins the importance of shielding the inhabitant, it also demonstrates the inherent contra diction: a need for closure is entwined with a desire for increased mobility.

Control

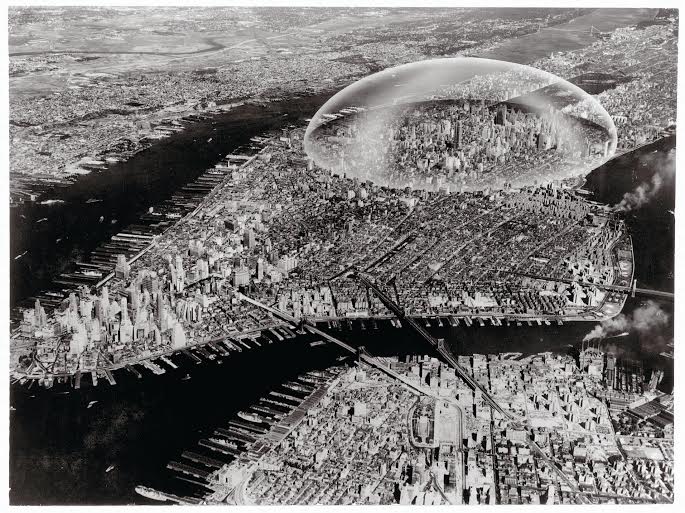

While Kurokawa saw architecture as a means for an individual to filter and control their desired degree of (dis)connection, a decade prior to Kurokawa Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao proposed an intervention that could partly disengage an entire city from its surroundings. Their proposal was a tensegrity dome over 3km (two miles) high, which would cover over 50 blocks of Manhattan. The entire structure could be erected within six months by a fleet of 16 Apache helicopters. As the dome rose over the downtown New York, the skin itself would be almost invisible. Fuller stated, ‘From the inside, there will be an uninterrupted contact with the exterior world. The sun and moon will shine in the landscape, and the sky will be completely visible, but the unpleasant effects of climate, heat, dust, bugs, glare, etc. will be modulated by the skin’. His disconnect was one from the outside environment rather than technology itself. The dome would filter the external environment in order to maximize the controlled interior. In this proposal the individual could no longer control their environment; instead it was the role of architecture itself.

Block

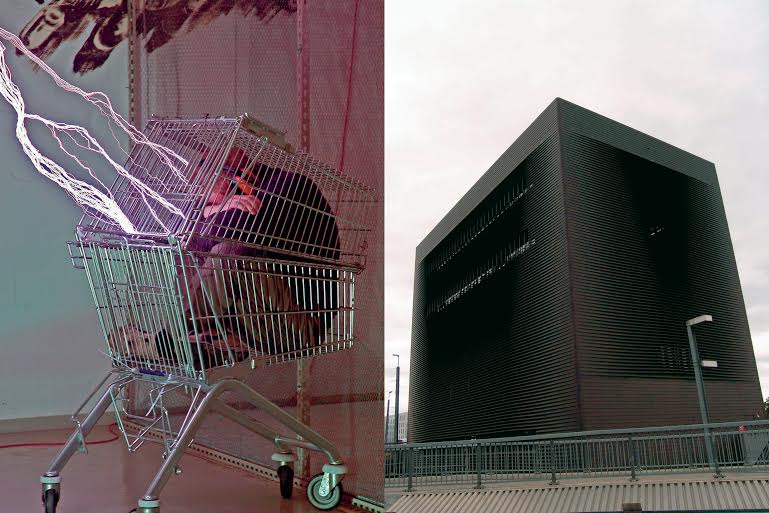

The montage of the Bucky dome over New York City echoes the entrenchment of the force field in the science fiction genre during the same era when the invisible shield became a protective device for intergalactic space craft and cities to deflect the attack of enemies or contain oxygen. While the sci-fi force field may appear fantastic, the basic principles of a force field were discovered by Michael Faraday in 1836 and aptly called the Faraday cage. The scientist discovered that a charge on a charged conductor had little effect upon anything lying within it. To test this premise he constructed a room lined with metal foil and charged the outside with an electrostatic generator; he discovered that no electric charge was present within the walls. This fundamental discovery has been leveraged at many scales from booster bags (foil-lined shopping bags to stop the RFID tag from beeping while shoplifting) to the British Secret Intelligence Service ziggurat on the Thames that repels virtual attempts to eavesdrop within its walls. Herzog de Meuron also built a Faraday cage with their commission for the Swiss Federal Railways Signal Tower 4. The imposing concrete block tower is wrapped by 20 cm (eight inch) copper taping bands like an electrical coil. Not only can entire buildings be isolated by solids, but researchers at the University of Tokyo have invented paint with aluminium-iron oxide, that, like the logic of the Faraday cage, absorbs radio waves: it blocks phone calls, keeps the wifi network secure, and prevents potential radiation exposure (in hospitals). With the heightened communication of objects in entirely new relations, architecture is located at the crux. As a mediator of the built environment it has the potential to provide strategic spaces of disconnect, both imposed and individually controlled, like from being stuck in the London underground or turning off push and location notifications on the smart phone. As buildings become smarter and mediate their relationship with outside forces more intelligently will future architecture aid our ability to know when to pull the plug and switch off? Or alternatively, is there a way for it to re-connect us when someone or something else pulls the kill switch?