Schooling the World

When I was asked by the editors of Volume to finalize my research about global investments in education I was excited. I spent days reading reports on education by UNESCO and other institutions. So finally the day of writing came and I bitterly realized that creating a unitary global narrative was impossible. I struggled to write something that made sense, mixing up different facts and statistics I found. The result was far from satisfying and pretty confused. How do you write about education financing from primary school to higher education, from Zanzibar to South Korea? Financial investments in education varies so much from country to country, and geography does not really help out in this regard; even mapping is a tricky task. So I started applying reason to this confusion itself. Why was it so difficult? The first answer that popped up in my mind was: too much data. All those statistics coming from all over the world… I seriously did not envy the UIS (UNESCO Institute of Statistics).

Suddenly I found myself thinking about how the UIS collects and elaborates the data. The UIS is not only one of the biggest statistical institutes in the world, but also the only one seeking a comprehensive global approach due to UNESCO’s mission, the UN agency dedicated to promoting peace through, education, science, culture, communication and information. UNESCO was born with the foundation of the United Nations right after the WWII when it became clear that economics and politics alone were not sufficient to secure peace. The basic idea is that it is possible to educate people to peace through culture. For this reason UNESCO is famous for heritage conservation, but its function extends to educational policy-making. The modus operandi of UNESCO is to set goals to be achieved on a global scale every fifteen years. During that time, projects are run, data is collected, and reports are compiled. For education, the last cycle started with the 2000 World Education Forum in Dakar, during which time the objective was set as ‘Education For All’ (EFA). EFA is a global commitment towards expanding accessibility to education to everyone and accelerating this process through global policies. Unsurprisingly, it was not achieved by the end of the cycle, this year.1

As an agency, UNESCO has the duty to report to the member states about its projects and progress. The monitoring task necessary for this is carried out by UIS, which is meant to analyze global trends in a reliable way; expressing nothing but objectiveness and neutrality. Is that really so though? Is it possible to create a global narrative, not to mention an objective and neutral one, out of local data? For this reason I began reading the forewords of any report I found on education financing. What I discovered is that the UIS has two main problems in preparing reports: collecting and comparing data.

It would be an understatement to state that achieving 100% statistical coverage on a global research project is a challenge. There are so many logistical troubles: political censorship, lack of staff or even war in some cases. As an example we can take a regional report published by the UIS on education, Financing Education in Sub-Saharan Africa (2011). It contains a lot of specific information regarding ‘all’ aspects of education with regards to its financing. It deals with GDP, gross enrollment ratios, gender equality, drops out and private funding. It is an interesting report and the very first of this type regarding Sub-Saharan African countries. But then I read that this report was published with a statistical coverage by 67%. This means that for 33% of all Sub-Saharan African countries, the UIS has no data. This lack clearly represents a huge problem for the veracity and integrity of the ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ narrative being pictured. In the foreword, UIS director Hendrik van der Pol writes:

This report is largely the result of efforts by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) to improve the production and use of education finance data. […] The project aims to build the capacities of national statistical teams in order to develop and implement sustainable mechanisms to regularly produce and use education finance indicators.2

According to the foreword, in 2005 statistical coverage of the area was by 13%. While the report was published in 2011, all the data for it was collected between 2000 and 2008. This means there was indeed incredible improvement since 2005, but I would argue that the result is still not satisfactory. The actual narrative created by the UIS is limited. Without proper data is not possible to track progress or to appropriately address the issues it sets itself out to do. On the one hand it is true though that this is not entirely the fault of UIS because, as mentioned before, some technical troubles are just overwhelming; in some parts of the world collecting data can literally be lethal. On the other hand, all those partial statistics are compiled in ‘global’ reports, whose logical effect is magnification.

It’s not just collecting data that can depict false narratives, but also comparison is risky business. To quote from ISCED 2011, the report presenting the updated statistical tools:

As national education systems vary in terms of structure and curricular content, it can be difficult to benchmark performance across countries over time or monitor progress towards national and international goals. In order to understand and properly interpret the inputs, processes and outcomes of education systems from a global perspective, it is vital to ensure that data are comparable.3

In 2011 UIS, UNESCO, Eurostat and OECD team up to improve ISCED, the International Standard Classification of Education. ISCED is the metric of comparison adopted by UIS. It was first created in the 1970s, modified in 1997 and then again four years ago in 2011. ISCED is fundamental to understand which standards education is compared with, and so evaluated. ISCED deals with different levels of educational programs, divided chronologically and combined with fields of education.4 In the report presenting its updated statistical tools, ISCED 2011, for instance, there are nine separate levels of education, from preschool to doctoral programs. The most updated version covers a wider temporal spectrum and includes the evaluation of qualifications, but still does not distinguish between different fields of education, such as: Art and Humanities, Social Sciences and Information, Business and Law, etc. UNESCO is currently developing ISCED Field of Education and Training,5 a new tool that will be integrated with ISCED 2011, which provides a distinction between different fields of study, making comparisons more reliable.

It is not merely a technical issue to create such an instrument. Classification always implies a judgment. It comments on how close an object is to a pre-set standard, which already creates a certain narrative per se. So it is basic to question what this standard is, who set it and for what reason. What I want to focus on in this essay is not the different levels ISCED focuses on, which are pretty technical, but on its lexicon. ISCED was created to frame educational programs, so its basis is ultimately in their definitions.

In ISCED, an educational programme is defined as a coherent set or sequence of educational activities or communication designed and organized to achieve pre-determined learning objectives or accomplish a specific set of educational tasks over a sustained period. […] A common characteristic of an educational programme is that, upon fulfilment of learning objectives or educational tasks, successful completion is certified.6

According to this definition ISCED is designed to categorize and to estimate two types of learning: what they call ‘formal’ and ‘non-formal’ education. The former is institutionalized, intentional and planned through public organizations and recognized private bodies, such as schools. The latter is institutionalized, planned and organized by an education provider, yet take the form of short courses, workshops or seminars and serve to complement formal education, or even be an alternative to it. International data collection is primarily focused on formal education, because of its ties to the country’s public education system.7 ‘Informal’ education, defined as non-institutionalized education, is excluded unless it leads to a recognized credential. So it has statistical value only after completion, which means that enrollments, a significant statistic, are not considered. As it has been suggested above, the main requirement for an educational program to be included in the international data collection is to provide an official qualification upon completion. ‘Incidental’ learning is obviously excluded by any research in the field.

Although this frame is comprehensible due to practical needs, it is most definitely not enough to claim to create an accurate picture of global education. In some countries, ‘non-formal’ education is attained more than ‘formal’. BRAC, an NGO focusing on children’s and especially girls’ schooling in rural areas of Bangladesh,8 runs 30,000 ‘non-formal’ primary-schools. Their model is so successful that the government decided to adopt BRAC’s method for the country’s public schools.9 Furthermore in both Europe and the US there is a growing interest for ‘informal’ education, whose main argument is its freedom from institutionalization. As you can see, data collection standards are incredibly specific and totally non-universal. Knowing who decided upon these standards may help comprehending why they were made in that way.

These improvements were introduced by a global technical advisory panel, comprising international experts on education and statistics including relevant international organizations and partners, such as Eurostat and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The extensive review process included a series of regional expert meetings and a formal global consultation coordinated by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) in which all UNESCO Member States were invited to take part.10

ISCED 2011 is clearly a collective project. What I think is interesting is that within this group of organizations, only Eurostat and OECD are explicitly mentioned. Eurostat is the official statistics institute of the European Commission, and OECD, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, is an international organization meant to stimulate international trade and economic progress. It has thirty-four member-countries of which four come from the Americas (Canada, USA, Mexico, Chile), two from Asia (Japan, South Korea), two from Oceania (Australia, New Zealand) plus Turkey and Israel. All the others are European states, and there are no African countries included. For this reason the main criticism towards it is the exclusivity of its membership for the richest countries.

All countries involved in OECD and Eurostat are main UN donors. This leads us to the reason why education financing reports are considered important. When someone wants to invest money in a project, they need a report. These reports list the strengths, weaknesses, threats and opportunities of the project. It is of no surprise then that ISCED 2011 is part of the economical and social classifications of the UN. I argue that the economic outcomes of education represent the main concern of countries in evaluating educational systems. Research and Development (R&D) is one of the primary objectives being sought, and therefore tertiary education is the main sector being boosted. Universities are particularly important because of the fact that in them basic research is carried out. Different studies confirm that academic research has an incredible economic return. For example Edwin Mansfield, professor of economics at University of Pennsylvania (1964-1997), carried out a study in which he discovered that one-tenth of new products and processes commercialized between 1975 and 1985 would not be existing if not for academic research.11 Moreover it has been calculated that US Federal investments on the Human Genome Project between 1988 and 2010 amounted $3.8 billion with a return of $796 billion.12

If a ‘proper’ educational system is not present in a country, efforts are put into expanding it starting from primary school. For example, with the financial assistance of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, fifteen Sub-Saharan African countries have adopted a fee abolition policy since 2000. Although this strategy did not provide the same results in all countries, it was fundamental boost for primary school enrollment. In Burundi, the most striking result of this policy, net enrollment rate increased from 41% in 2000 up to 94% in 2010.13

Since the Second World War, investment in R&D has been regarded as one of the key strategies to secure technological potential and, therefore, innovation and economic growth. The evidence is plentiful, in particular for high-income countries.14

The more people that reach university, the more economic growth is secured – in the eyes of funders at least. This is the primary reason behind worries about dropouts in primary and secondary education in low-income countries. Human capital has to be increased and trained at the highest standards to be competitive.

Many cross-country studies demonstrate a virtuous circle in which R&D spending, innovation, productivity and per capita income mutually reinforce each other and lead countries to long-term sustained growth rates. […] A central characteristic of R&D is that its payoffs are not limited to the original investors […]. As knowledge gradually leaks out, private benefits decline and spillover effects increase.15

Education and knowledge seem to have a pivotal role in assuring a stable economic growth. Both are instruments for creating human capital able to reach tertiary education and go on to research and develop. Every analysis and report points to the fact that the institutionalization of education programs is economically productive. Different kinds of learning, ones that are not proven to have appealing economical outcomes even if framed within ISCED, are not the main focus of UNESCO reports. The comprehensive global approach that the UIS is meant to have is unfortunately undermined by the narrow perspective adopted in its tools. Moreover the effect of political and economical interests on its instruments accompanied by evident logistical troubles on data collecting completely deny any global narrative to be pictured. So then we should ask ourselves: if a neutral unitary narrative is impossible, what should we strive towards at the global level?

References:

- EDUCATION FOR ALL 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges, UNESCO, Paris, 2015. The EFA program was also part of the 2015 Millennium Development Goals.

- Financing Education in Sub-Saharan Africa | Meeting the Challenges of Expansion, Equity and Quality, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Montreal, 2011.

- ISCED 2011, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Montreal, 2012, p. III.

- A field is the “broad domain, branch or area of content covered by an education programme or qualification”. ISCED FIELDS OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING 2013, UNESCO Institute of Statistics, Montreal, 2014, p. 5.

- The first draft was developed in November 2013.

- ISCED 2011, p. 7.

- ISCED 2011, pp. 11-12.

- Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee

- Sukontamarn, The Entry of NGO Schools and Girls’ Educational Outcomes in Bangladesh. London, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2005.

- ISCED 2011, p. III.

- Mansfield, E. (1991), Academic Research and Industrial Innovation, Research Policy, No. 20 pp. 1-12.

- Higher Education in Asia: Expanding Out, Expanding Up. The rise of graduate education and university research, UNESCO Institute of Statistics, Montreal, 2014, p. 51.

- EDUCATION FOR ALL 2000-2015, pp. 80-84.

- Higher Education in Asia, p.49. Although the report is mainly focused on Asia, those countries represent the widest recognized example of foreign intervention for development and the most recent case of massive scale economical growth out of university research.

- Higher Education in Asia, p.49.

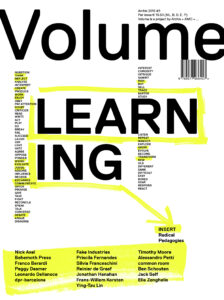

This article was written to accompany Volume #45, ‘Learning’.