Producing the Metropolitan

Interview with Joachim Declerck

Flanders has long been cast as a nebular city of hyper individualized sprawl – everyone with a house and a view to the landscape – the result of a welfare state ambition that flourished after the Second World War. Joachim Declerck wants to rethink the spatial logic of this situation, recalling the historical strengths of the original city-states, this time translated to new transnational realities. With his practice, Architecture Workroom, he’s brought two new projects to the International Architecture Biennial Rotterdam and the Venice Biennale, which discuss these issues. Volume sat down with him to discuss scales of intervention, re-situating production, and the metropolitan fabric.

AO: You’ll be presenting a project at the Venice Biennale discussing the idea of the metropolitan delta, a transnational metropolitan system in which Flanders is positioned. What’s the starting point for that project?

JD: Certain things are changing at the global scale, which is, that we’ve long lived with the assumption that wealth is produced and that the biggest task is to redistribute that wealth. We’ve also assumed that cities should be places of consumption, and that consumption is a very important function of the city. I don’t believe we still live in a condition of welfare, where wealth is being produced by something very abstract and then we have to redistribute it. Wealth is produced in urban areas and hence these urban areas should be arranged spatially as well as governed in terms of their productive capacity, from the very small-scale to the very large-scale. I use the Brussels example, where the service economy is no longer the only destiny for the city. We had agriculture, then we moved to industry, then we moved to a service economy. The logical question would be: what’s next, after services? But in fact, what you see is that agriculture, industrial activities, and services will co-exist in urban areas. So we have to drastically change our conceptions because all of our urban policies of the last two decades were geared towards the service economy and the service economy only.

That’s the first point: it’s a global thing. We should shift from the idea of a network of service hubs as the planning principle for metropolitan systems, and allow for production again, from agriculture and small-scale manufacturing, to creative industries, informal economies, and so on. And this requires another form of planning.

The second thing is a territorial manifestation typical of Flanders and probably extremely guilty as a landscape. Since the Second World War and longer, Flanders has developed as a territory of consumption. So the landscape has been consumed – literally. And that is also because of political decisions and strong policies. As Michael Ryckewaert describes, the Belgian form of urbanization is the territorial manifestation of the welfare state project, which means: individual ownership and stimulating the dream for every individual to own their home on a plot that faces the landscape. That dream is constructed, decided upon, and supported by politics and has become the economic system of Flanders.1

Within Flanders there’s a territorial dynamic that is different from the dynamic outside of Flanders. We see that this form of consumption of territory leads to all sorts of problems and does not inscribe Flanders as a (coherent) region in terms of achieving a global metropolitan dynamic. If we want to achieve that, we need a new strategy to accommodate the one million new inhabitants expected in Flanders by 2050. If we allow ourselves to urbanize without a drastic break from current policies, we will continue to urbanize in a dramatically unsustainable way and strengthen the anti-urban feeling that is physically embedded in the landscape.

There’s another option however, if we look to history. Our settlement pattern hasn’t really changed since the Middle Ages. There is the same system of cities present and they still produce most of the wealth. We should play on this strength by making them perform in a more ‘metropolitan’ way. To develop them as metropolitan regions, each of the cities has its own particular capacity and quality – historically it’s a system of complementary cities that produced this region, this delta, where the most productive lands in terms of agriculture, best water quality, fisheries, and so on were strategically allocated; and hence these cities are the best place to urbanize.

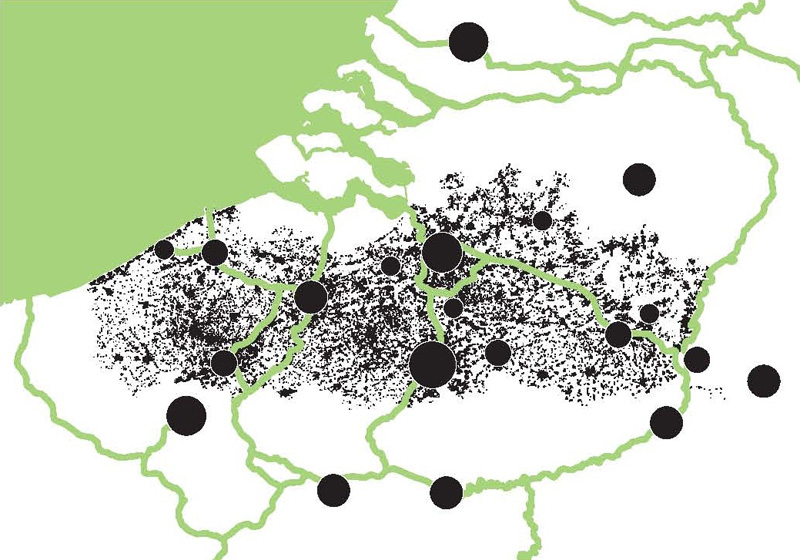

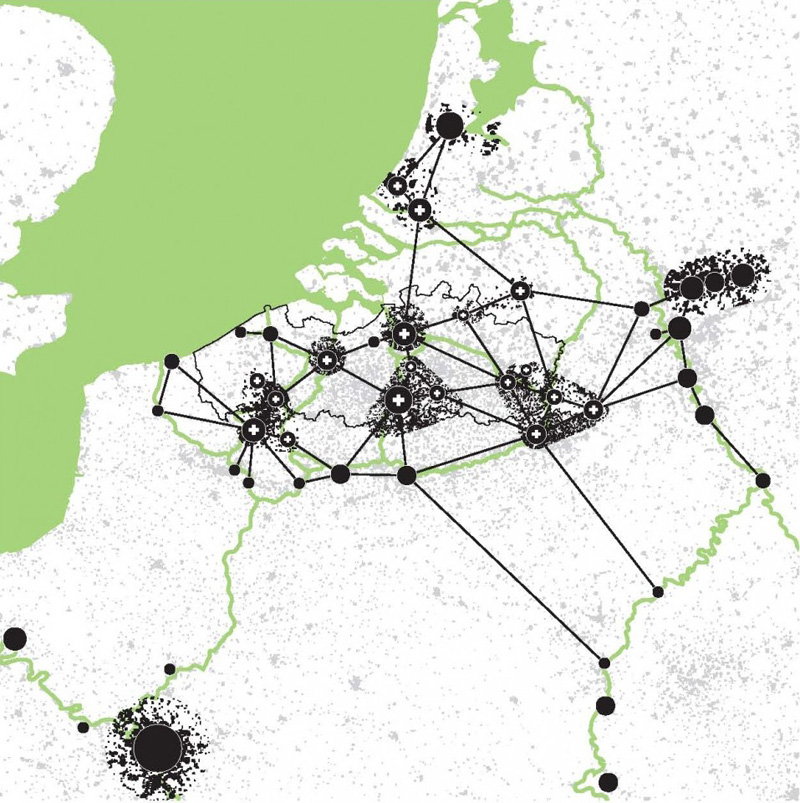

This delta situation is transnational. This is the case for its history, but also for the major challenges and opportunities that are embedded in this territory: those things do not respect borders. We see this more and more everyday. We see it with the rising water levels in the Rotterdam area; we see it with the increasing of flooding in the Flemish areas; we see it with the salinization of water in Flanders. So the complex of all these ecological, economic, and urban situations – which is this delta – requires us to think differently. We need to stop the welfare project as a project of territorial consumption, and build upon the historical system of cities to develop metropolitan regions. A system of pearls that does not see this whole region as one singular system, but distinguishes different territories in this delta. These are not just the historical cores of cities, but bigger portions of territory that can function as socioeconomic units and that can become territorial projects.

That’s an incredible task, which is clearly lying ahead of us, but which requires us to rethink policies as these territorial units cross national boundaries. In Belgium it’s clear that Brussels is outside of Flanders and that the planning of Flanders often goes against the planning of Brussels. The Eindhoven (NL)/Turnhout (BE) region on the other hand, there is a clear regional development here, where the towns need to work together. Then there’s a region in search of a future, the region of Maastricht (NL)/Aachen (DE)/Hasselt and Liège (BE). Then you have the former textile industry around Kortrijk (BE) and Lille (FR). Here you have newer economies that are very productive now, stronger than the textile industry such as food processing. These are economies that are also transnational and we have to find the right level to work on them.

If we look at the history of Flanders in political terms, it has no singular identity, and it never had. The region of Lille and Kortrijk has a different identity than the region of Brabant around Brussels. So there’s another narrative to be told about Flanders, which is not one of a welfare state with a territorial project, but one that’s built on historical centers – because that’s where socioeconomic wealth is produced – and that inscribes that into a project for the future. The reason to do this, and that’s the argument we are trying to build, is that currently the strongest forces in terms of wealth production are outside Flanders. Lille is the engine of that region. Aachen and Maastricht are more of an engine than Hasselt or Genk; also Liège is more of an engine. Brussels is outside of Flanders. Rotterdam is necessary to make Antwerp effective (you see the political debate about deepening the Scheldt).

As opposed to this vision of Flanders, our political debate is mostly dominated by parties that try to convince the population by comforting them: while completely confirming the welfare state’s anti-urban feelings, they are claiming that our wealth can be maintained as long as we can redistribute wealth within our national territory, which is Flanders, and not to these other regions around us. They construct the false promise of a Flanders that will continue to be successful as long as its regional/national territory is governed by the region itself. These dominant voices neglect the fact that Flanders is historically a part of a broader territory and system, and that it is this transnational urban system that will produce our future wealth — not a national or regional territory. And still they say they are explicitly pro-European! Instead, there is an objective need, in terms of ecology, in terms of economy to shift focus. To paraphrase something Bruce Katz said, “Countries do not have an economy.” They are statistical zones where you measure wealth. Cities have an economy. So let’s focus on these transnational city regions. Make them function.

AO: It would seem that to be effective you’d have to produce urgency. So what is the urgency that you’re going to advocate?

JD: I think we’re living in times with an abundance of urgencies that we absolutely need to focus on. There’s not a day that the newspaper doesn’t report on the ecological, energetic, social, demographic, or economic urgency. But we’ve made these questions so big and abstract, that we don’t do anything with them. They seem insurmountable. We have been hoping that a supranational organization would come up with responses to these global or supra-global questions. But that is not and will not be the case. So we need to find bridges between what we can do and the urgency; and the city region or those territorial units are such bridges: this is a scale at which those super-human urgencies are clearly felt and become manageable.

BC: Can we say that another chance to act comes in the form of the Spatial Policy Plan for Flanders? Because it’s being drafted now and is only made every twenty years, isn’t this the chance to shift the way we think of the region?

JD: Well you could say that the hope would be that this plan succeeds in translating abstract needs to territorial systems at a city-regional scale.

But there’s another urgency. Why do Kris Peeters [Minister-President of Flanders] and Mark Rutte [Minister-President of the Netherlands] conclude that they have to collaborate economically? Because I think that they see – and are told by the port authorities – that collaboration is strictly necessary. The report produced by the Clingendael Institute demonstrates that without collaboration there is no future for the port economy of the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt Delta, and the economic system around it. So this economic urgency is felt in both Belgium and in the Netherlands. On the other hand, the ecological urgency is only felt on the Dutch side: you have the delta program2, which focuses on an urgency that literally comes from the ground, from the territory. We don’t have that at all in Belgium. Going back to looking at the historical genesis of these cities, they were settled in places not by coincidence but as strategic locations, that are still strategic locations. But also there’s something embedded in the territory, which are systems of water management and so on that you can activate to give meaning to an urban region, so to combine all the interests, you could say.

The first step in dealing with such urgencies is to territorialize them, to draw them, and make them understandable and their potential influences readable – to my mother for instance. And that’s not that difficult. And then the next step is to make policies function in terms of urgencies and not in terms of the existing system. Because the lens that the system has cannot see the forces at play nor the territorial cohesion of problems, because the system has the wrong lenses.

AO: If the nebulous city that is the Flanders region was produced by an economic policy, it was and still is a reflection of a political reality. It produces the kind of life and reality that the people want. It delivers.

JD: It was a debate between the Christian Democrats and the Socialist party, the latter being pro-urban, for historic reasons (social revolts). The Christian Democrats who are still in power now, were in favor of this nebulous urbanization. So the ideal has, to a certain extent, been fabricated by political choices and policies. In the framework of the Flemish Spatial Policy Plan that is in the making, a poll of the Flemish population was made and revealed that the citizenry understands that we have to live more compact, that our transportation system can’t remain the way it is. So people know, and are ready to accept this reality.

But imagining how the economic system can function differently then, that’s not so easy. We urbanize horizontally and the economic machinery behind our current system likes it, and grows, while the landscape quality and agricultural production goes down. How can you develop systems where things can work together?

AO: Or you can draw it in other terms, such as a national problematic, and that produces another view on the issue.

JD: Exactly. So the urgency to create the climate for discussing new solutions is work for designers. By drawing these problems, to discuss and use design to explore new solutions. So how do you develop a system at a regional scale in which you do not only have the idea of the compact city? For the compact cities, we have a set of policies that have been relatively successful over the past two decades, but which have also proven to be dysfunctional for other parts of the territory: we cannot copy this continuous urban fabric onto the rest of the city region. We need to work on the horizontal recomposition of the functions that are laid out in this territory. How do we make them into something, into a fabric that includes agricultural production and industrial production for which we need to find space, since they have been pushed outside of cities? These are all functions of the city as a metabolism, which we will increasingly need to feed ourselves, to make our urban society more and more self-sufficient. And that’s a design question that we as professionals have very few ideas about yet.

AO: At the level of acting and doing, we’re seeing things in a more complex way, and we want to address it in a more intelligent way, integrating the various factors involved and that indeed is complicated…

JD: It’s simple and complex. There’s something simple to be told. Put bluntly, we know we need to move to a more sustainable form of civilization. The city is that form. It’s there where we will produce our income and our welfare. The ecological problems can be solved easier in cities, and demographically people are moving to cities. It is interesting to observe that the sustainability argument has only recently started to embrace the city: the Green parties were formerly against the city, but they are no longer. That is a very important shift. To combine ecological awareness with urbanization, that’s a good progression. And then you have the difficult story. Our system, our institutional architecture, is not outfitted to deal with this.

BC: I want to pick up with what you were saying about the need to capitalize on the productive capacity of cities. From a global perspective in the West we’ve more or less stopped producing things, having shifted everything to the East. Yet the forms of urbanization that have sprouted up there to accommodate production are totally undesirable for Western ideals. What I find shockingly under-researched is what a newly productive Western city could look like.

JD: You see the dynamics. Globally we thought we were the brains, and the hands could be somewhere else. Suddenly it appears that India and China have brains too. Oops. So we have a little problem. Unions are being formed in China, salaries are slowly but continuously going up. In fifteen to thirty years, the wages there might be the same as they are here. In fact we’re moving to something that is equalizing. Which means that American firms are already starting to return back to the US with manufacturing plants. These are things that are currently unimaginable, but at a small-scale it starts happening. But where in our landscape will we accommodate this return? So that’s something we’re exploring with our submission to the Venice Biennale.

As a side step to this conversation: to talk about economy at an event like Venice, as a cultural actor, is really not done. Our commissioning party, the Flemish Architecture Institute first labeled us as neoliberals for doing so. But I think it’s not neo-liberal at all. Take Brussels for instance, the one that believes that the poverty within the capital region can be remedied by the tertiary sector is foolish. That is unimaginable. Brussels is the third richest region in Europe because of this tertiary sector, but the other part of the population, for whom we didn’t plan anything, is not and will not become connected to this economy. So that requires another form of economy. So that kind of question is already in our cities. How can we connect this growing tendency at a global scale (the return of production) to these problems that already exist in cities? I’m not just talking about large manufacturing plants, but also small urban economies. How can we stop counting everything in terms of GDP, working only in terms of the highest production value?

In terms of social sustainability, we will need to work and plan for that productive city, small-scale production – and also for farming. But not in terms of rooftop farming, which undoes the idea of a relationship to the productive territory to something that is gimmicky. A very interesting story in this context, I believe, is the Atelier Istanbul, which we coordinated on behalf of the local authorities in Istanbul and the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR). On the land of a local municipality in the northern green belt of Istanbul, you see very clearly that farmers from Anatolia are moving to Istanbul in the hope that they can leave the economy of agriculture and animal husbandry, and enter into the urban economy. But that perspective, that idea of progress – going from agricultural to industrial to knowledge economy – is something that we need to stop. There’s a lot of farmland within Istanbul that needs to be intensified. You need farmland to combat against the urban heat island effect, but also to protect drinking water resources from urbanization. So, together with HNS Landscape Architects and 51N4E, a strategic vision was developed that did not focus on how the urban could develop, or on how the farmland could develop, or on how the water could be produced. The strategy integrates those different questions into one systematic response – into a logic. And that’s what I meant with ‘horizontal recomposition’. The logics of these different systems need to be synchronized.

There are two cycles we need to break. The first is the idea of inevitable progress from agriculture to industry to tertiary. The second is that the urban always has more capacity to buy land than the agricultural or the natural.

AO: Who’s going to organize that?

JD: We can help doing that. But we cannot be alone. The incredible pleasure at this moment in working with and on behalf of an architecture biennial is that it can bring so many of these different actors together around the table. And hence, a number of these questions are simultaneously put in front of the design discipline and of the political discipline. They are new questions. What I see as our main role, as Architecture Workroom, is to be sharp in defining these questions, which in turn allows for precise design work in collaboration with other parties. And that in turn allows for modifications in our current system of governance. That seems to be working. For the Venice Biennale, we’re now working with the Association of Farmers in Flanders, for example. They see that there’s no future for farming unless they have an urban vision for farming. They are increasingly aware of that. Well why isn’t it represented in policy? I think the slowest will be the policymaking, the system of governance. But civil society will lead in its search for profit and for solutions. In the end, we can show and represent where profit can be made within a longer-term perspective, and where it can be combined with other interests for win-win situations.

AO: Is it a self-organizing process then?

JD: No, not at all. It needs political leadership. But the discussion between bottom-up and top-down is a false one. We’ve identified more or less five different actors that need to be involved in their different capacities to make things work: the political side, the market side, civil society, design, and operators – the ones who operationalize (transport companies, social housing corporations, etc). These five all need to function in different ways and together to effectively respond to urban challenges. And the funny part is, looking at the 33 projects that are part of the ‘Making City’ IABR, this seems to be happening everywhere, so how do we capitalize on that? How do we build on the fact that ideas and information are no longer the sole responsibility of the government, which means that they are shared? In that sharing it means that a platform like a biennale is a place where things are made, not where things are presented. And that is what is very motivating. That is what gives the cultural sector a new role and mission. With my organization Architecture Workroom, we are convinced that we can – and I hate the word because it has become so trendy – ‘co-create’ responses to urban and architectural challenges, in collaboration with other actors.

AO: Back to Venice, Peter Swinnen in a recent interview mentioned the he was busy bringing politics to Venice, which he said was a mind-boggling enterprise.3

JD: In my view, that is not easy because it is a matter of undoing architecture of the immediacy of the signature of the architect. It’s a matter of giving authorship a different position; a very important position but a different one. Not politicians hiring signature architects, but politicians naming very important questions, translating those into spatial questions, and using design to animate and guide a process towards concrete urban transformation. And it’s not that design therefore does not get any value. Design has an extremely strong value in that respect. It’s not Le Corbusier going to the minister saying: I can solve it for you. It’s a complex, always changing, dynamic process, in which you don’t solve everything all at once.

AO: Many people see the relevance of architecture as a socio-political factor practically ending with the rise of the starchitects, the last phase of the definite throwing overboard of architecture at large.

JD: Well, but let’s capitalize on that. Is it negative that Rem Koolhaas is extremely famous and is taken up in a think tank for the European Union? Let’s say there’s incredible potential. Did something come out of it? Maybe. I don’t know if the energy study [Roadmap 2050] is literally linked to that, but the energy study is made. It’s there. It’s a more meaningful study than many other studies. Do I think it’s completely thought through? No. But is it good that it’s done? Absolutely. The next step is to de-AMO-ize it. If Koolhaas would operate more as a curator or mediator, than as an office, that would probably bring us a step further. So if he would rather be the one formulating the question, than the one responding to the question, that would seem more sane. To always do both is a side effect of this starchitects movement. And that is a bit sick. But we must build on this situation and the chances it offers, rather than rejecting it.

BC: That’s one thing that we’re talking about in this issue, is the need (and tendency) to start thinking at a mega-regional scale, with mega-regional plans. And what you’re talking speaks to that. But…whereas now a kind of criticality is emerging, mega-regional planning is still a foreign zone in our practice.

JD: Yes I think it’s a foreign zone, but I think it’s important to say that, the fact that we look to this mega-region delta. Do you need a plan for that as a whole? Well it’s going to be a very different kind of plan. You don’t need to ‘plan’ at this scale. You need to intervene at certain points; the same goes with the metropolitan scale. We have this history of plans with arrows and patches of color. I don’t think that’s what’s needed at this scale. I would use the example of the ‘Bordeaux 50,000 Dwellings’ project in this context. It is an initiative launched by a politician, Vincent Feltesse, who is trying to combine a political strategy – trying to win the next elections is the default mission of any politician – with an innovative urban trajectory. The project explores how the agglomeration of Bordeaux can actively steer, instead of passively observing, the construction of the next 50,000 new housing units in Bordeaux. How can these homes increase and intensify the metropolitan quality of the most horizontal city in France, rather than functioning as new towns. What this shows is that the largest scale, the metropolitan project, can be constructed through the extremely small.

AO: There was much talk at a recent presentation that you attended about the bypassing of notions of the center and periphery. What is your take on this?

JD: I think the notion of the ‘metropolitan’ mostly achieves that; it doesn’t negate their existence but acknowledges their comparative strengths and weaknesses. The metropolitan is something that accepts the fact that the core city has mostly things and remains to have things that we will not find anywhere else. Can I do my work in the periphery? No way. But are there things to be reorganized on the periphery? Yes. And do you need other relations in which urbanization is not about just working in the city and having the periphery as the hinterland that just depends on the city? Yes that’s clear. It is also clear that we have to find a way to break the link between the urban or metropolitan and density. The focus should rather be on intensification, on urbanization of that periphery, that horizontal system of functions that do not conglomerate into something coherent. So to explore and design new forms of conglomeration is a clear task.

Notes

1. Michael Ryckewaert, Building the Economic Backbone of the Belgian Welfare State: Infrastructure, planning and architecture 1945-1973 (Rotterdam: 010 publishers 2011) 2 See Volume 31; Guilty Landscapes…

2. The Delta law (2011) is a Dutch program that integrates protection against sea-level rise and inland flooding, and includes provision of fresh water, desalination, and ecological balancing.

3. Peter Swinnen interviewed by Arjen Oosterman and Brendan Cormier ‘Ambition as Antidote’ in Volume 31: Privatize!. 2011: 4.