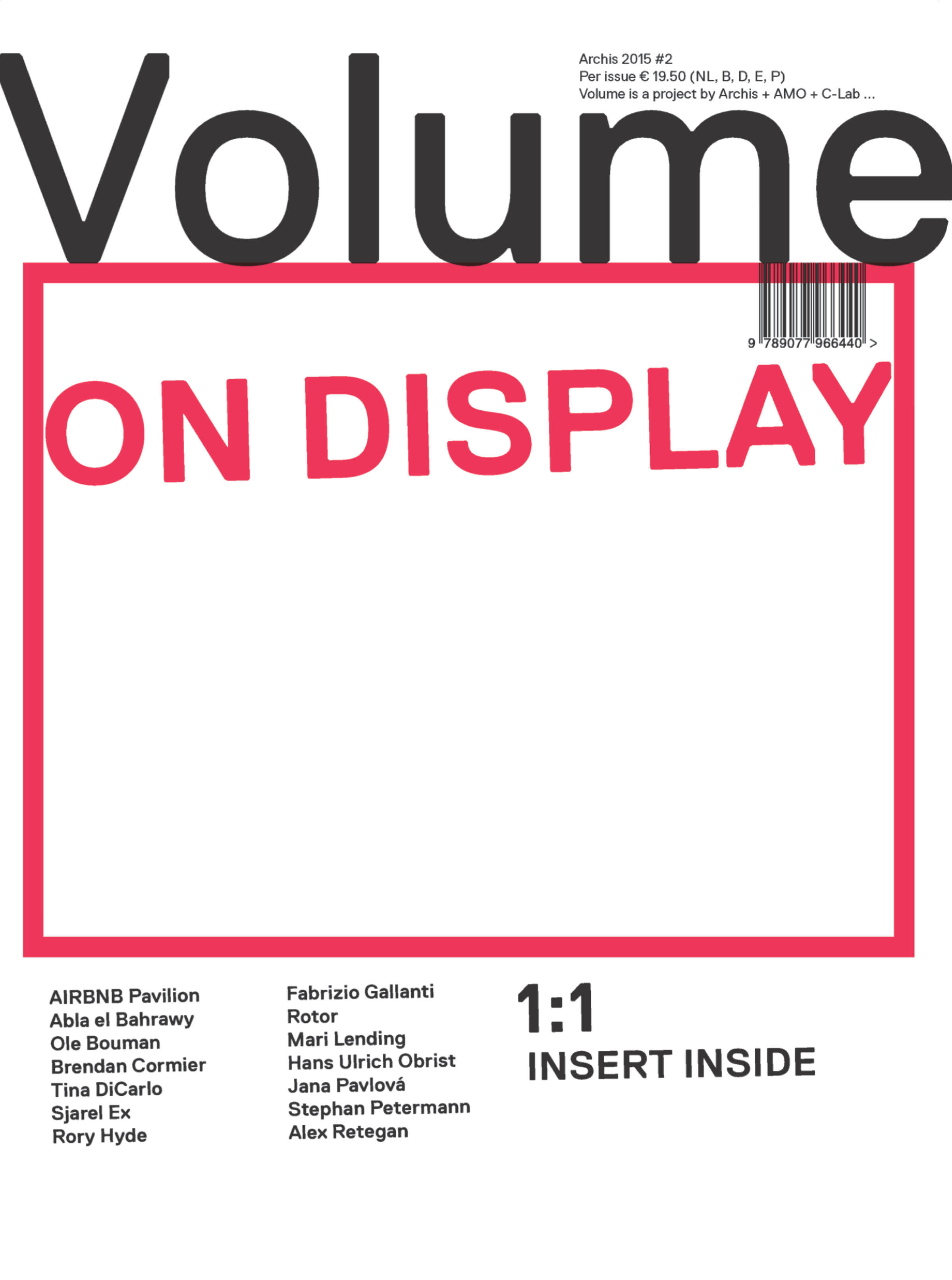

On Display

One of the more recent phenomena in a city’s public space is the ‘wrap’. Passing through the city, all of a sudden a familiar face is hidden from view, covered by a mesh of steel tubes and fine-grained nets. This all has to do with scaffoldings’ safety regulations, erected for a building façade’s maintenance. The nets hung around the temporary structure hide the building from view, making one wonder what it’ll look like when the job is done.

Maybe the more familiar association of wrapping is with giving; the wrap ritualizes the act, postponing the moment of surprise for when the gift is liberated from its packaging. It stresses that the act is as important as the gift itself, an essential component in this ‘bonding’ ritual.

The building owner’s gift to the city is the rejuvenation of his property – fresh looks – or a makeover, usually called ‘upgrade’. In the meantime, the wrap introduces a semiotic game of sorts, made more complex by the use of the wrap’s surface as blank canvas. As measure of precaution, it performs as an element of suspense – the announcement of a piece of architecture’s renewed display – but also transforms into a billboard and transforms the city likewise. The wrap displays another message, creates another space as part of the ‘brandspace’ phenomenon. (1)

When the temporarily wrapped building has monumental quality, the owner can decide to replicate its image on the wrap’s surface, a Shroud of Turin, and in doing so attempt to neutralize the disturbance caused by the construction work. That this option is available at all has all to do with developments in printing technology, but the phenomenon itself underlines that once a monument, a building primarily displays itself. The building is the message.

Message rhymes with broadcasting and that suggests we’re on familiar terrain. One of architecture’s histories is that of the art of display: architecture displaying power, political ambition, economic success, social agendas, or less mundane notions like dreams, convictions and belief. Architecture is one of the oldest media to use to such ends. So what happens when architecture itself is subjected to display as regime, when it becomes one of the candies in the city’s gift box? And who’s doing the display anyways?

The word ‘display’ is associated with selling, with shop windows, with commerce. If something is on display there, the owner wants to get rid of it, and the object can change hands when the price is agreed upon. Display ‘objectifies’ the object. That becomes problematic when the ‘softer’ or less visual values of architecture become overtaken; its inherent violence, for instance, or its ability to move (emotionally). The reductive tendencies of the hyper-attention economy (be seen or disappear) add to this effect.

Let it be said however, that display is not a condition one can simply push aside or escape from. Scientists are well aware that display plays an essential part in interpersonal behavior and the reproduction of society. The networks within which architecture is put on or puts on a display have expanded, dramatically. What, where, how, why and by whom architecture displays and is displayed has a reflexive influence on architecture. That is a point this Volume wants to make and one of the reasons it started to take a wider, and closer, look at the art and architecture of display.

References

1. Brett Steele, ‘Brandspace’, Archis no. 1 (2001), pp. 9-17

This article was published in Volume #44, ‘On Display’.

This article was published in Volume #44, ‘On Display’.