Grenfell: Between Test and Reality

In Volume 38 – The Shape of Law, Liam Ross investigated the gap between built space and the laws that regulate it, exposing the paradoxical nature of building codes by jokingly applying them to the RIBA Gallery in London and the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Abandoning all jokes, this essay deals with the tragic fire of London’s Grenfell Tower, and more precisely, with the (ongoing) inquiries with which the responsible ones are supposed to be identified. A difficult task, Liam argues: because of the ambiguities written into British building standards, and because of their excessive number, which make them available to be intentionally “gamed”.

The origin of the word “test” is the Latin testa, a “piece of burned clay, earthen pot, or shell”. Its contemporary English usage originates from the role such pots played in “assaying”, in melting the ore to test the purity of the metal. Fire has also been used as a means to test the “mettle” of people. The medieval “trial by fire” was a means to test the conviction of a defendant by testing their faith. The rationale was that, if they were innocent, they would trust God to protect them from burns while running barefoot over hot coals. Through the concept of the test, the trial, the assay (and in turn, the essay) we are reminded that fire is a part of the infrastructure of science and law, a means to reveal hidden qualities in people and things through the differential effect it has upon them.

At the time of its occurrence, the Grenfell Tower fire was popularly conceived of as a “trial” for the then Prime Minister, Teresa May, the “Hurricane Katrina moment” of her waning premiership. Occurring in the early hours of 14t June 2017, the fire consumed a tower-block in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, causing 72 deaths and 70 injuries. The casualties were mostly council tenants and mostly from ethnic minority backgrounds. Grenfell was the deadliest accident in Britain since the end of the Second World War, ten times as deadly as the Great Fire of London. The high death toll was attributed to the rapid external spread fire through a cladding system that had been recently installed by the local council. That council, which is Conservative-led, had previously sought to demolish the tower and its surrounding estate to create room for new development. Council documents suggest that the cladding was designed primarily for the tower’s affluent neighbors, rather than its tenants, a means to limit the negative impact of a post-war social housing project on neighboring property values. Furthermore, Tenants had expressed concerns about fire-safety failings of the renovation, some of which were material on the night of the fire, but were ignored by Kensington and Chelsea’s Tenants Management Organisation. Indeed, one tenant association predicted the fire, suggesting it was the only way that problems with the building, and with its governance, would be revealed: “Only an incident that results in serious loss of life … will allow the external scrutiny to occur that will shine a light on the practices that characterize the malign governance of this non-functioning organization”.1

At the first Prime Minister’s Question Time following the event, Jeremy Corbyn sought to enroll the event in a broader policy critique, suggesting that the event had revealed failings and loopholes within current fire-safety regulations. Grenfell was, he claimed, evidence of “the disastrous effects of austerity”, “the terrible consequence of de-regulation”, and of the government’s “disregard for working-class communities”. He sought to do this by connecting the event to the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order, an act that had recently abolished mandatory fire-safety checks on new buildings. That act was the keystone policy of a deregulatory agenda pursued by successive governments since 1997, initially through Tony Blair’s “Better Regulation” Taskforce, then through David Cameron’s “Red-Tape Challenge”. But Corbyn’s “essay” quickly floundered; investigations revealed that the fire brigade had carried out numerous fire-safety checks at Grenfell, but had no authority to comment on cladding construction.

The fire has since prompted a number of other investigations, likewise intended to judge whether regulatory failings were responsible for the event. The first to conclude was Building a Safer Future: The Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety. Commissioned by the government, and Led by Dame Judith Hackitt, it published its findings in May 2018. The Grenfell Tower Public Inquiry, ordered by Teresa May, and led by Sir Martin Moore-Bick, is ongoing at the time of writing. Already the largest and most costly in British history its first phase report, published in October 2019, sought to establish the facts as to what happened on the night of the fire. Lessons learned from the fire await a second phase, which is yet to conclude.

This paper is an attempt to follow those parallel inquiries, to explore the way the Grenfell Fire might be seen to ‘test’ the UK’s legislative frameworks. It begins by outlining the rationale of Building a Safer Future. That document, it will suggest, sought to use Grenfell as an argument against prescriptive standards, and to promote further deregulation. The chapter continues to consider evidence presented at the Public Inquiry, concerning the ignition and spread of fire through the cladding system. It suggests that by following fire as it moved through that physical structure, we can identify weaknesses within that building, our legal frameworks, but also Hackitt’s argument. The chapter concludes with a reflection on the government’s later decision, contra Hackitt, to impose a ban on combustible cladding. It considers the different forms of knowledge that fire-safety regulation needs to negotiate, and why in this case prescriptive codes appeared the only means to do so. The ambition of this essay, then, is also to test Corbyn’s argument; it seeks to connect the Grenfell Tower fire to the neo-liberal governmentality, to deregulation, if here by socio-technical rather than explicitly political means.

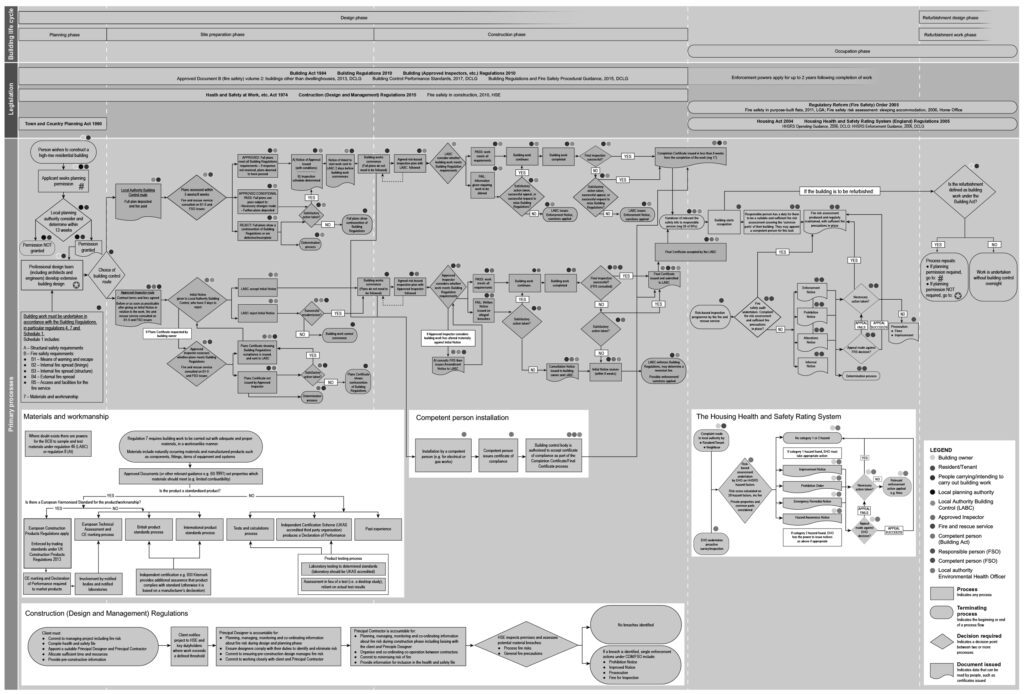

Ownership of Risk

Building a Safer Future was, in many ways, a scathing critique of the UK’s building regulations. According to Hackitt, our regulatory frameworks are not “fit-for-purpose”. The complexity of those frameworks are, in her view, a key part of that problem. Hackitt takes care to map out graphically (Figure 1) the multitude of current legislation that pertains to fire-safety, across the various stages that make up the life-cycle of any British building project; the Building Act, the Building Regulations, Health and Safety at Work Act’s, the CDM Regulations, Fire Safety in Construction regulations, the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order, the Housing Act and specific Housing Health and Safety regulations. She shows how each of these legal frameworks overlap in time, drawing differently on a wide array of stakeholders: the owner, consultants, contractors, and builders, planning and building standards authorities, approved inspectors, residents, and the fire-and-rescue service. Taken together she finds these frameworks “highly complex – involving multiple routes, regulators, duty holders and differing (and overlapping) sets of legislation”.2 She suggests that this system constructs a lack of clarity over discreet roles and responsibilities, allowing risk and responsibility to fall between them. Hackitt acknowledges that recent deregulatory initiatives have contributed to this situation. She recognizes that private sector certification, the ambiguity of performance-based standards and the lack of supporting governmental expertise have created a “competition of interpretation” that drives a “race to the bottom”, through which individual actors have sought to “game the system”. Nonetheless, Hackitt fundamentally supports “outcomes-based” regulation; she is opposed to the creation of additional prescriptive standards. Indeed, Hackitt suggests that we already have too many prescriptive codes, which in turn attribute too much responsibility to the government. For Hackitt, the root cause of Grenfell was not a lack or gap in law, but rather a surfeit, one which by existing, freed individuals from taking responsibility.

Source: Hackitt, Judith. ‘Building a Safer Future: Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report’. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2018. p. 14 www.gov.uk/government/publications

It was because of this view that Hackitt’s report was met with immediate political and media critique, being dubbed a “disappointment… betrayal and whitewash”.3 For opposition MP’s and most journalists, it seemed clear that the root cause of the fire was the prevalence of combustible cladding at a height that could not be extinguished. There was a widespread sense that a ban on such combustible cladding was required. Hackitt’s refusal to propose one was read as a refusal, by government, to acknowledge any responsibility for the event. Defending her report in light of its reception, she argued that “simply adding more prescription, or making amendments to the current system, such as restricting or prohibiting certain practices, will not address the root causes”, which again she contended were the result of poor engagement with and enforcement of existing guidelines.4 There has been much speculation as to why Dame Hackitt did not move for such a ban, with claims of a conflict of interest; in a previous role, Hackitt led a body that approved and promoted cladding and insulation similar to those used in the tower.5 Those concerns notwithstanding, the rationale of her report is clear. What Dame Hackitt calls for is a transfer of responsibility away from government, whose role should be limited to one of setting broadly defined performance standards. The detailed guidance used to demonstrate compliance with those goals should, in her view, be left to experts and be open to innovation. What this would support is a clearer “ownership of risk”6; what our regulatory framework should define is not particular rules, but rather “clear responsibilities for the Client, Designer, Contractor and Owner to demonstrate the delivery and maintenance of safe buildings”. From that perspective, banning flammable materials would be counter-productive; a new regulatory framework, she argues, must be,

truly outcomes-based (rather than based on prescriptive rules and complex guidance) and it must have real teeth, so that it can drive the right behaviors. This will create an environment where there are incentives to do the right thing and serious penalties for those who choose to game the system.7

Incentives and penalties are particularly important for Hackitt. Our regulatory frameworks become effective not by offering more guidance, but by identifying moments of failure. It is events like Grenfell, and its Public Inquiry, that shape this “environmentality” of governance. Prosecutions for regulatory failings are what make the system strong. From this perspective, it is imperative that the Public Inquiry identify a guilty party, in breach of code, and to discipline them.

Socio-technical Complexity

What Hackitt proposed was a new regulatory framework that would make attribution of responsibility clearer. She recommended a consolidated set of regulations for High-Rise Residential (HRR) buildings, gathering existing guidance in one document. She proposes this by suggesting that High-Rise equals High-Risk; that tall buildings come with specific attendant fire-safety concerns. The truth of this assumption, questioned by expert witnesses to the Public Inquiry, is beyond the scope of this essay.8 What I wish to dwell on in Hackitt’s report is a socio-technical metaphor she employs about the design of regulatory frameworks. If the regulation of high-rise residential buildings is to secure the engagement of those involved in their construction, she suggests that it must be designed in the image of those buildings. It must recognize “the reality of most high-rise buildings, which operate as a complex interlocking system”.9 The root cause of the Grenfell fire was, in her opinion, that responsibility for fire safety was not properly defined, it “fell through the cracks”. The key ambition of her proposed framework is to make it clearer who and what component in that building carries the responsibility for fire safety, so as to understanding precisely where and when they fail.

I draw attention to Hackitt’s metaphor – that our regulatory frameworks must be constructed like our buildings – because it seems to recognize the way changes in construction practice have changed their attendant fire-safety risks. We can see this by comparing the original structure of Grenfell Tower with that of its renovation. The original tower was built, owned and managed by the state, largely out of a single, non-combustible material, concrete. The risk that this structure created, and the way that risk was distributed, was quite monolithic. Since that tower was built frameworks for procurement, construction and tenure have changed dramatically. Buildings are more complex materially, they employ more components, and construct more gaps between those components. At the same time, the design and construction of buildings are more socially complex, involving a greater number of stakeholders. The Grenfell recladding project is an example of this. It involved a wide range of different interlocking building components, designed, certified, supplied and installed by a wide range of different actors. These physical and legal complexities, both noted by Hackitt, are related. Contemporary modes of the procurement and certification of building design are means to break up the liability for construction into smaller component parts, to isolate actors from certain risks while still allowing them to enjoy certain rewards. What Hackitt seems to recognize, if tangentially, is that such practices can in parallel increase fire risk.

Following fire

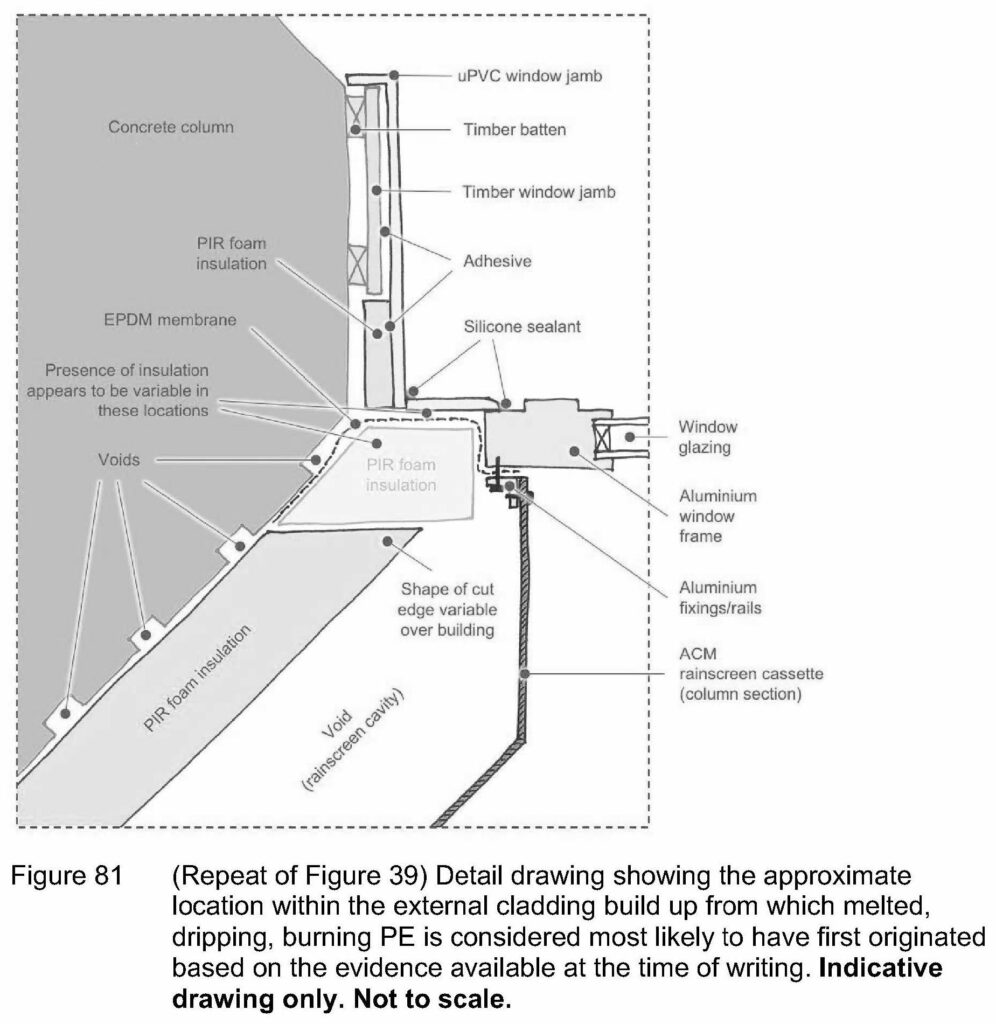

“I am confident that the fire started in the Kitchen of Flat 16 (Level 4), in the area near the window… most likely spread to the cladding via gaps or holes which formed in the polymeric window framing boards that surround the kitchen window, and also through the weatherproofing membrane and thermal insulation, all of which were installed during the 2012–2016 refurbishment. The fire most likely then penetrated into the back of the cladding cavity and ignited the polyethylene filler material within the aluminium composite material (ACM) rainscreen cladding cassettes that form the majority of the building’s exterior surface. The fire appears to have spread to the cladding, and started escalating up the East Face of Grenfell Tower, before the first fire service personnel entered the kitchen of Flat 16 and attempted to extinguish the fire within the building. The primary cause of rapid external fire spread was the presence of polyethylene filled ACM rainscreen cassettes in the buildings refurbishment cladding system. Other factors that may also have contributed to the fire’s spread include: the use of combustible products in the cladding system; the presence of extensive cavities and vertical channels within the cladding system; and the use of combustible insulation products within the window framing assemblies.”10

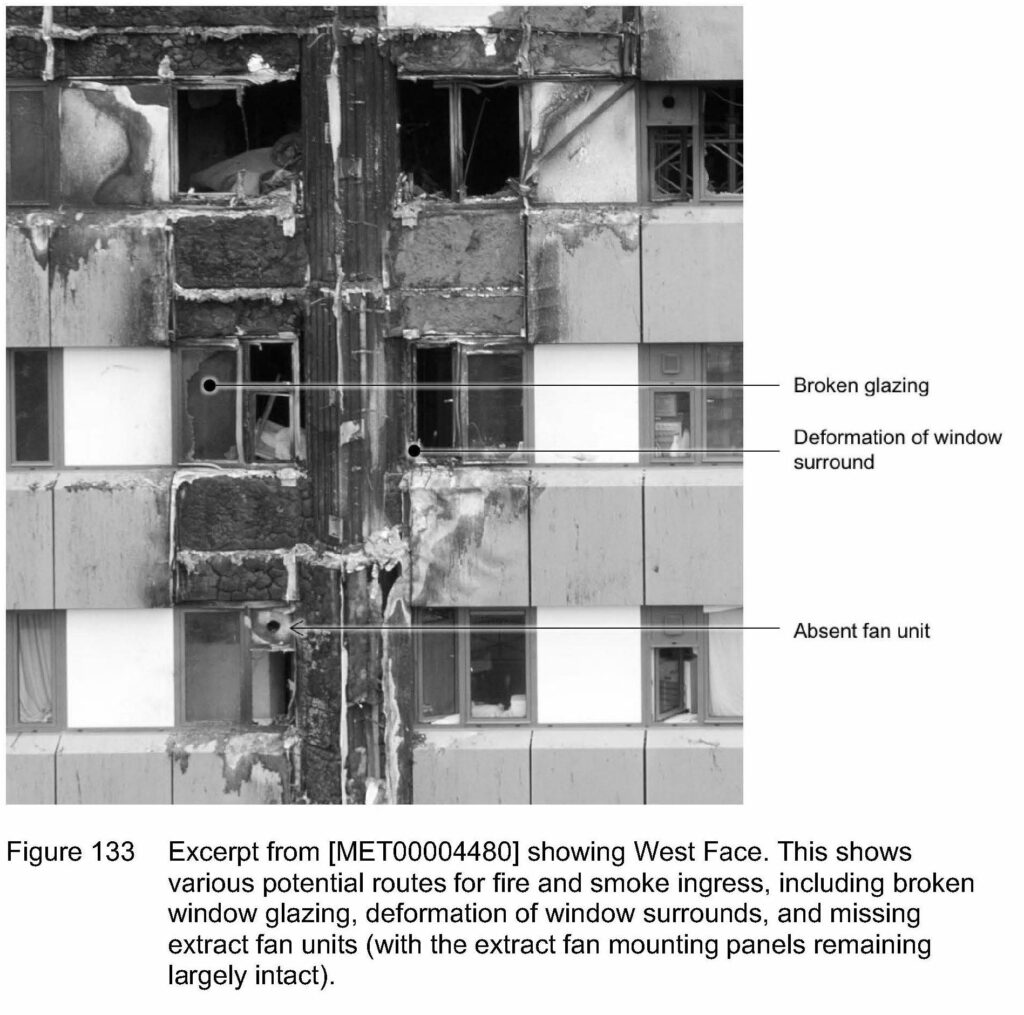

The above quote is an extract from an expert witness provided to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry on 4 June 2018 by Luke Bisby, Professor of Fire and Structures at the University of Edinburgh. Bisby was asked by the report to identify where the fire started and how it spread through the building. The above is his summary. These findings were not controversial; his report confirmed the widely held view that the fire most likely spread through flammable filler material located between the original concrete structure and the refurbishment windows (Figure 2). The phrase I wish to stress here is “most likely”. In the introduction to his report, Bisby spends some time noting the “extraordinarily complex technical challenge” of determining the precise trajectory of any fire through forensic examination. Furthermore he notes that, at the Grenfell Tower, that job is made all the more difficult by the nature of the cladding, which is itself “a highly complex system, consisting of multiple materials and products, many of which are combustible”.11 Bisby describes how the fire spread to the cladding first, but also how many different ways it travelled there, and how many other ways it could have gone; fire certainly travelled through gaps between the window and the structure, but it also travelled through an extract fan, through filler around the fan opening, by burning through an infill panel, and through the open window itself (Figure 7.3).

Source: Bisby, Luke. ‘The Grenfell Inquiry: Phase 1 Expert Report’. Grenfell Tower Inquiry. University of Edinburgh, 2018. p. 128. https://www.grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk/evidence/professor-luke-bisbys-expert-report. (accessed, August 24, 2021)

Source: Bisby, Luke. ‘The Grenfell Inquiry: Phase 1 Expert Report’. Grenfell Tower Inquiry. University of Edinburgh, 2018. p. 202. https://www.grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk/evidence/professor-luke-bisbys-expert-report. (accessed, August 24, 2021)

Explaining the process through which fire propagates, Bisby outlines the process of pyrolysis, or “fire separation”. As things burn, they are separated into their component parts. For instance, wood does not “burn” directly; its cellulose decomposes when exposed to heat, turning into a gas which then oxidises in the atmosphere, releasing heat that then continues this chain reaction. At the component scale, fire likewise separates and deconstructs constructional arrangements. While the cladding panels and window arrays used at Grenfell do not ignite directly when exposed to a flame, when a sustained fire takes hold near to them their material assemblies begin to delaminate, melt, deform, exposing flammable components. That is, fire poses a particular threat to materials and constructional arrangements; it decomposes them, creating and exploiting gaps between their component parts. What is conspicuous about Bisby’s description of the fire is the sheer quantity of potential lines of failures. The refurbishment project included a wide range of different components, many of which were plastic, and many of which were flammable, creating multiple possible vectors for the spread of flame.12

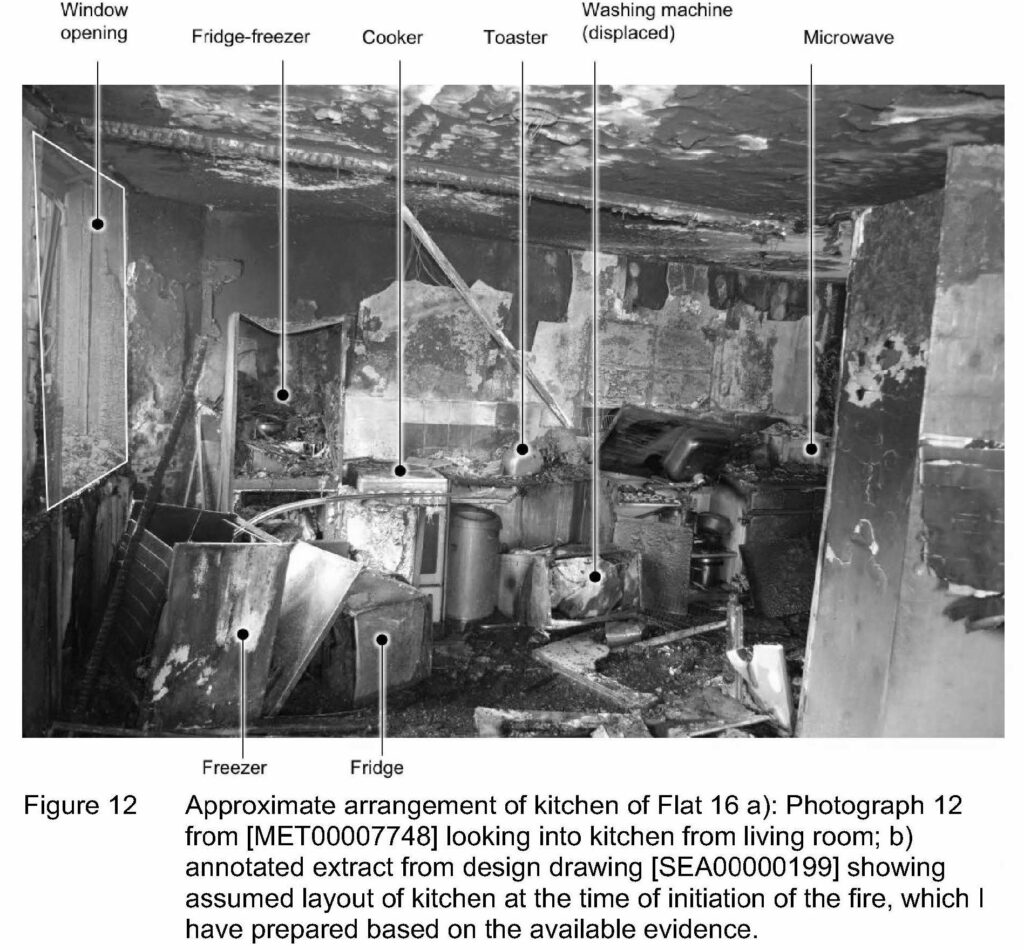

The question of how the fire originated was posed to another expert witness, José Luis Torero, then John L. Bryan Chair in the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at the University of Maryland. Again, his report begins by noting the complexity of the task presented: “Fire evolves in space and time leading, in many instances, to a complex sequence of events and multiple processes and activities occurring simultaneously”. The source of the Grenfell fire had been popularly attributed to a malfunctioning fridge within the kitchen of flat 16 (Figure 7.4), but Torero finds no evidence to confirm or contradict that existing view: “[A]t the date of submission of this report, there is no conclusive evidence that constrains the cause, origin and initial stages of the fire to a single timeline or set of events”.13 Torero does confirm that smoke from a malfunctioning refrigerator could have melted the nearby kitchen window, exposing flammable components within the buildings external cladding. UPVC loses its mechanical properties at around 90°C, whereas the smoke from such a fire would likely be 100–200°C. However, he goes on to demonstrate that the same result could have been caused by a pan-fire, or, indeed, the malfunction of almost any common appliance (the Lakanal House fire, of 2009, which also spread via a window, to the external cladding, was started by a faulty TV). As such, he suggests that the specific source is not only unknown but also irrelevant:

From a design perspective, a fire of 300 kW occurring in a residential kitchen, and in the proximity of the window, should be considered to have a probability of one. A fire of this nature will happen in a residential unit and therefore the building is required to respond appropriately.14

Source: Bisby, Luke. ‘The Grenfell Inquiry: Phase 1 Expert Report’. Grenfell Tower Inquiry. University of Edinburgh, 2018. p. 33. https://www.grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk/evidence/professor-luke-bisbys-expert-report. (accessed, August 24, 2021)

If Bisby and Torero appear circumspect about pinning down the precise origin or route of the fire, their attitude might be understood with reference to literature on fire-safety investigations and standards. In “The Regulation of Technological Innovation: The Special Problem of Fire Safety Standards” Vincent Brannigan reflects on a problematic tendency in forensic fire science. He suggests that, under pressure to identify clear points of responsibility, forensic fire investigations often conflate the source of ignition with the cause of catastrophe. When done accurately,

analysis of disasters shows just how complex the chain of causation can be in a specific accident. But regulators face an even more complex task since they have to analyze and interrupt these chains of causation before they occur and across the entire spectrum of scenarios.

A focus on the ignition is, he suggests, usually an attempt to divert attention from that complexity, and so from the failure to regulate fire spread. By stressing the irrelevance of ignition, and the multitude of possible routes, Bisby and Torero seem to support Brannigans critique. But their testimony might also cast doubt on the importance that Hackitt places on identifying and prosecuting a single point of failure responsible for such catastrophes. The ambition to do so might conflict with that of identifying wider, more complex, and more structural concerns.

Legislative Pyrolysis

As the fire moved through the filler materials, infill panels, insulation and cladding system at Grenfell Tower, it tested the physical strength of those components, but also of their associated fire-safety claims. A key question for the Inquiry was whether those components met with relevant fire-safety standards. That question is a legal proxy through which to identify who should bear responsibility for the event. The conservative government in the form of Phillip Hammond was quick to state that the cladding used on the building was banned for use in the UK.15 He was backed up in this claim by the Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) – the body that oversees building regulation in England – who released a statement that: “Cladding using a composite aluminium panel with a polyethylene core would be non-compliant with current building regulations guidance. This material should not be used as cladding on buildings over 18m in height.”16 These statements would seem to insulate government from any claim of regulatory negligence, and facilitate prosecution of the contractor. The clarity of those claims quickly came apart, though. The contractor Rydons claimed that the design “met all required building control, fire regulation and health and safety standards”.17 This ambiguity was not helped by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, the owner of the tower, client for its renovation and also the body responsible for warranting its compliance with building standards. Shortly after the fire they revealed that a warrant had never been issued for its refurbishment: designs had been submitted to, and reviewed by the council, but “a formal decision notice was not issued for the plans”.18

The ambiguity that allowed Phillip Hammond and Rydons to make contradictory claims are examined in detail by investigative journalists Peter Apps, Sophie Barns and Luke Barrat, reporting for Inside Housing. They show that such ambiguities are, unfortunately, written into our building standards. In England and Wales, the performance specification for external fire spread is defined by mandatory standard B4 (1), of Approved Document B. This regulation states that “The external walls of the building shall adequately resist the spread of fire over the walls”.19 It might seem self-evident that the cladding used at Grenfell Tower – a Reynobond composite comprising two 0.5 mm-thick aluminium sheets fixed to a 6 mm-thick core of polyethylene – fails to satisfy this standard. Polyethylene has an extraordinary fire-load; “If you look at a one metre by one metre square section [of cladding] that will have about three kilograms [of polyethylene], the equivalent of about five litres of petrol.”20 But that material can be shown to meet the prescriptive requirements associated with standard B4. Paragraph 12.6 of Approved Document B states that the external surface of an external wall will meet that standard if it achieves a “Class O” rating for surface spread of flame. Reynobond’s aluminium cladding systems were certified to achieve that rating by the British Board of Agrément, through a test that involves exposing their aluminium face to flame. In that test, when exposed at its centre, the aluminium layer did not separate to reveal the polyethylene core, and the composite product was classed as a permissible “surface”. The interior of that surface was simply not visible to this means of testing, and as such was ignored by those who later specified it. As some would put it, “It’s not within the imagination of the [industry] that the panel can come away and expose the flammable materials behind.”21 After Grenfell DCLG did appear to become more imaginative: in order to sure up what might seem like a regulatory failure, it released a statement noting,

For the avoidance of doubt the core (filler) within an aluminium composite material (ACM) is an ‘insulation material/product’, ‘insulation product’, and/or ‘filler material’ as referred to in Paragraph 12.7 … of Approved Document B.22

The significance of this statement is that insulation products are subject to the more onerous demand of demonstrating “limited combustibility”, being capable of surviving for at least 2 hours in a 750°C furnace. It would seem too late, on 22 June 2017, to avoid that doubt, and the need for parentheses within this statement – to change the name of what it sought to define – doesn’t help. It’s possible to call a cladding panel an insulant, even if it has no insulating function, but that doesn’t lend to clarity. This ambiguity has perhaps been useful for manufacturers, allowing combustible materials to be used in products that can nonetheless be certified to limit the spread of flame. However, that same ambiguity creates a divergence between test and reality, as well as making it difficult to identify or prosecute clear responsibility for such fires.

From Test Assembly to Specification

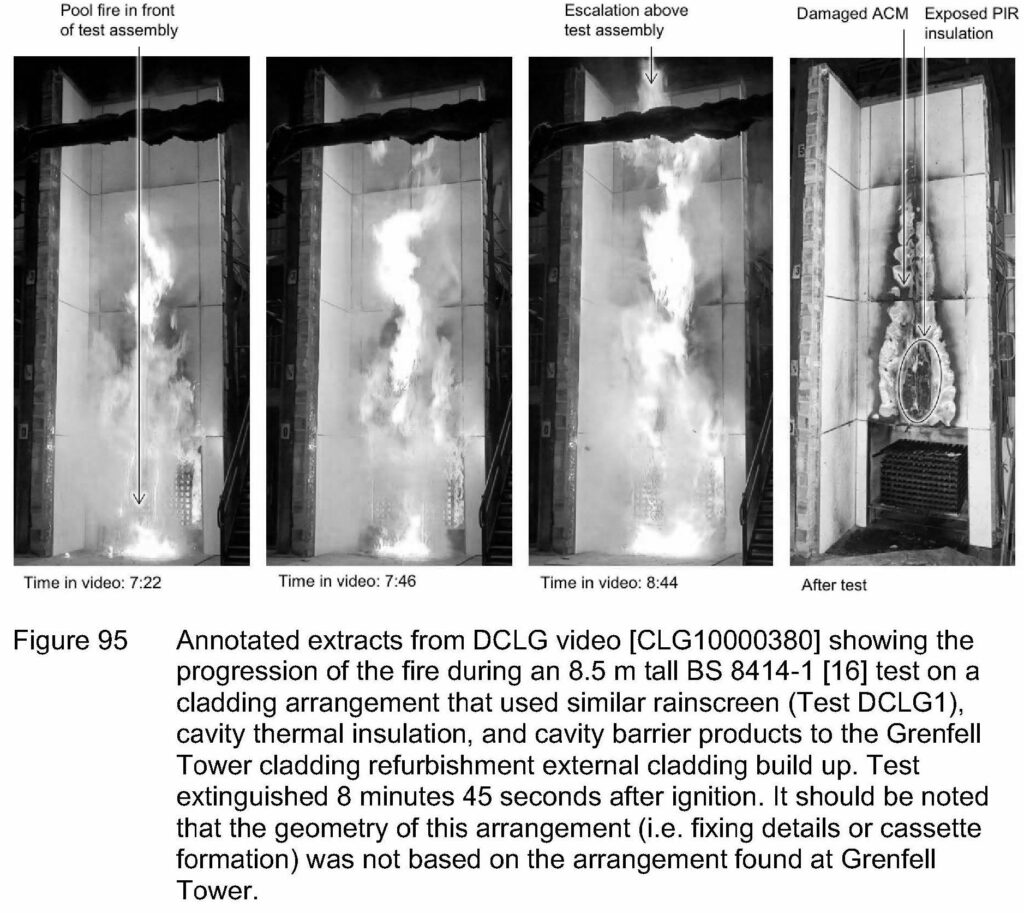

If this suggests a concern that the UK’s prescriptive standards are not fit for purpose, the Grenfell fire provides reasons to be concerned about “outcomes-based” standards, also. The polyisocyanurate foam insulation used on the tower, Celotex RS5000, was subject to the more onerous requirement of “limited combustibility”. While this material could not meet that requirement on its own, its manufacturers successfully argued that it can “adequately resist the spread of flame”, through performance-based codes. These forms of regulation were first developed by the Building Research Establishment (BRE), with the view to testing how whole material arrays, as opposed to individual buildings components, perform in fires. This form of standardisation operates through the use of full-scale mock-ups, which are themselves subject to a standardised test, defined by British Standard 8414: Fire performance of external cladding systems. Test method for non-loadbearing external cladding systems. That test requires the mock-up wall resist the spread of flame across its height for at least 30 minutes (Figure 5).

Source: Bisby, Luke. ‘The Grenfell Inquiry: Phase 1 Expert Report’. Grenfell Tower Inquiry. University of Edinburgh, 2018. p. 148. https://www.grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk/evidence/professor-luke-bisbys-expert-report. (accessed, August 24, 2021)

The construction and testing of full-scale mock-ups is time-consuming and expensive. It would be impractical to test every material assembly in use in buildings across the UK today. As such, this route to approval has gradually been subject to shortcuts and modes of deregulation. Today, wall assemblies are often approved on the basis of “desktop studies” – studies that argue that an assembly would survive a BS8414 test based on tests of similar assemblies – and those studies can be completed by any “suitable qualified fire specialist”. Furthermore by 2016 it had become common practice for non-governmental bodies – such as the Energy Saving Trust, Dame Hackitt’s former employer – to suggest combinations of materials, including those used at Grenfell, that might be used without the need for desktop studies. These relaxations have allowed the widespread use of components that on their own would not meet the requirement of “limited combustibility” without tests of any kind. This fact was recognised by Teresa May when, days after Grenfell, she announced that “a number” of other high-rise residential tower blocks within the UK might use a similar cladding system to that used at Grenfell. The effect of this announcement was the immediate evacuation of households from estates in Camden, the triggering of waking watches for effected buildings, and the beginning of an ongoing process to replace unsafe cladding, and to determine who should bear the cost of that replacement. Following that announcement, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government launched a series of tests, via BS8414, to determine the safety of ACM cladding more generally. 299 of the 312 social-tenure high-rise buildings tested by January 2018 had failed those tests and were deemed in need of re-cladding. Figures within the private sector – where this form of cladding and insulation is also widespread – are not known.23

The methodology of BS8414 subsequently came under scrutiny as a result of Grenfell. The closest full-scale test to the wall build-up used at Grenfell Tower had been completed by BRE in 2014. This tested Celotex RS5,000 in combination with a fibre-cement rain-screen. However, shortly after Grenfell, BRE released a statement withdrawing those test results. They had been made aware by the manufacturer of “anomalies between the design specification for the cladding system and the actual cladding system they installed to be tested.”24 BRE were keen to stress that they took no responsibility for the way in which the cladding system was constructed; this was strictly the responsibility of the manufacturer. If and how Celotex rigged that test is not clear; the results of BS8414 tests are confidential and proprietary. However, we can make an educated guess on the basis of research commissioned by the Association of British Insurers. This body – no doubt wary of its own collective liability – asked the Fire Protection Association to compare the parameters of BS8414 with the “real-world” conditions that it simulated. They found it to be unrepresentative in a number of ways: domestic fires often include plastics, and so burn hotter than the test recognizes; cladding systems are often tested as sealed units, when in reality they have ventilated cavities which provide conduits for fire-spread; and the test uses material in “manufacturers conditions”, when in practice they will be compromised by further openings, such as those required for vents and windows.25 All of these issues were identified by expert witnesses as material within the rapid spread of the Grenfell fire. But more damningly ABI’s report – which was submitted to Dame Hackitt and seems tacitly acknowledged in her introduction – alleges that some manufacturers “game the system” in precisely the way that BRE’s statement suggests, testing constructional arrangements that are not as per the published design specification. Specifically, they draw attention to a practice of riveting components in an assembly together, intentionally stopping them from delaminating when subjected to heat.26 The implication of their report is that far more than 312 towers are in need of inspection, via tests more onerous than those that have already found 96% of those tested to be unsafe.

Proprietary Knowledge and Public Interest

From the evidence reviewed above, the Grenfell Tower fire does support a number of the claims made in Dame Hackitt’s report. Grenfell has shown that our regulatory framework is not fit for purpose – indeed, that it is being intentionally “gamed”. Celotex is not the only manufacturer alleged to have rigged fire-safety tests for materials used at Grenfell Tower. Providing evidence to Phase 2 of the Inquiry, Arconic president Claude Schmidt likewise admitted that rivets had been used in test assemblies of products, despite their absence within design specifications. He recognized that when his product was tested in the cassette application specified at Grenfell, it failed those tests dramatically, witnessing emails that showed test results of the specified application should be kept “VERY CONFIDENTIAL”, and admitted awareness that those specifying the product were being misled.27 That the two products material to the spread of that fire both appear to have rigged fire-safety tests in the same way supports the ABI’s assertion that such practice is widespread. What this specific case does not seem to support, though, is Hackitt’s assertion that “outcomes-based” regulation is any less prone to misunderstanding or abuse. Abuse of testing procedures undermined both prescriptive and performance-based forms of certification for materials used in Grenfell’s facade. Both were subject to forms of verification that transferred responsibility away from those bodies created to assume it – Ministers, Local Authorities, the BRE – into proprietary procedures conducted by actors for whom a competition of interpretation is incentivized.

Returning to “neo-liberalism” and its role in the Grenfell fire, we can recognize that Hackitt’s report is based on an assertion that the market will discipline itself if an environment of rewards and punishments are put in place. So far, the Inquiry has not provided evidence that would allow us to judge that assertion. The Public Inquiry is not an inquest – its findings are not legally binding – and all criminal investigations are on hold until its conclusion. Nonetheless, it has revealed how resistant some actors will be to prosecution. Arconic representatives initially used blocking statutes to avoid giving evidence, statutes specifically designed to prevent French nationals giving evidence against themselves abroad; prosecuting national laws in the context of a globalized industry is not simple. Closer to home, the British Government has shown limited appetite to discipline those responsible for installing dangerous cladding on other buildings. That issue was addressed in the Fire Safety Bill passed into law in April 2021. While the bill offered limited financial support for those replacing cladding at a height over 18 m, it, nonetheless, defined the responsibility for that replacement as sitting with leaseholders. Despite an amendment approved in the House of Lords to this effect, the government specifically rejected any proposals that would ensure this liability was “owned” by those who designed, approved, installed or manufactured that cladding.

By following fire as it spread through the components and legislation that held Grenfell Tower together, I think we can also offer a more general critique of Hackitt’s govern-mentality. What we saw in Bisby and Torero’s reports, and in Brannigan’s argument, is that in any fire it is difficult to pin down singular points of failure. Fire is a kind of risk that spreads, whether we like it or not. Grenfell and catastrophes like it depend upon and reveal a multitude of failures, any one of which is both necessary and contingent. Cladding and insulation components were not the only ones to fail in the fire, just as Celotex and Arconic are not the only manufacturers to have abused our regulatory processes. Even if we choose to focus on this headline failure, what it points to more broadly is the failure of our standardized tests, that is, of the need to discipline government itself. BS8414 did not only allow individuals to “game the system”, as part of a neo-liberal “environmentality”; it tacitly supported that “gaming”; penalty and reward are the organizing poles of a competition, and the space for competition that BS8414 creates is the “black box” of proprietary testing. With 72 dead and an ongoing Inquiry, Grenfell made that game publicly visible, but also politically untenable, at least for a short time.

Between Prescription and Performance

I present the above argument in the hope of drawing lessons from Grenfell, but also to contextualize the apparent U-turn made by the UK Government shortly after the release of Hackitt’s report. In June 2018, the Ministry for Housing, Community and Local Government launched a consultation on banning combustible cladding on high-rise residential building, a ban that was put into place November of the same year. Pressure to do so had been mounting in the media, but its strongest advocate were architects. The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) set up an Expert Advisory Group on Fire Safety, whose published recommendation included a repeal of the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) bill, the abolition of desktop studies for demonstrating performance compliance, as well as further clarification of Approved Document B4, suggesting the inclusion of new prescriptive guidance, specifically a ban on combustible cladding at height. These recommendations corresponded closely to the political mood after Grenfell, but are directly opposed to those of Hackitt’s review, and the opinion of other experts testifying at the Inquiry.

Engineer Angus Law and sociologist Graham Spinardi reflect on those differing opinions in “Performing Expertise in Building Regulation: ‘Codespeak’ and Fire Safety Experts”. They note the wide range of different kinds of knowledge that the problem of fire safety gathers; the first-hand experience offered by tenants caught up in fires; the practical knowledge of fire-fighting offered by rescue teams; the empirical and theoretical knowledge offered by those who study or model fire behaviour. They note that, in relation to these stakeholders, those who design buildings and regulate design have a different form of understanding; they are not experts in fire, but in “codespeak”, in the language of regulation. Despite this being a particularly abstract form of knowledge, they recognize it in having particular virtues: “Although distanced from the fundamental empirical experience of fire, codespeak is powerful because of its relative clarity and certainty, and legal status.”28

What Law and Spinardi highlight is the fact that those involved in complex problems like that of fire-safety approach it from diverse and sometimes contradictory knowledge positions. There is a pronounced difference between the way engineers and architects, for instance, think about the problem of fire. Engineers are disposed to model and measure, to think in terms of equations and accuracy, to prefer “engineered” solutions, and so performance-based standards; that mode of regulation operates through their own disciplinary rationale, and generates a need for their own services. Architects, by contrast, are neither fire-safety experts nor qualified to conduct such calculations. Their work balances a wide range of competing concerns, usually through the resolution of spatial parameters. As such, they are disposed towards prescriptive standards, which allow them to satisfy fire-safety requirements through their own skill-set. Debates as to the relative virtue of these two modes of regulation are often shaped by a competition between these two disciplinary perspectives, as each stakes out their claim to “own” the problem of fire safety.29

Reflecting on why the RIBA’s approach was given precedence over that of other experts, Law and Spinardi offer a more general reflection on the virtues of prescriptive codification. They do so by first recognizing that fire safety is an “ill-structured problem”. The governmental objective may be clear and simple – “that the external walls of buildings shall adequately resist the spread of fire” – but the detailed definition of what constitutes “adequate”, and the variety of ways that might be achieved, is complex and prone to controversy. The problems revealed by Grenfell, explored above, related to this broader problem of adequately defining “safety”. The promise of performance-based standardization is to avoid representational simplification, to reproduce the problem at scale 1:1; to move from the “ill” to the “well-structured”. Nonetheless, the Grenfell fire has revealed that process to be fraught with opportunities for sophistry. In this particular circumstance, where the complexity of and competition between knowledge positions is itself a problem, recourse to simpler modes of standardization appear necessary. Law and Spinardi note that the familiar terms involved – a ban, on combustibility – alongside the authority traditionally ascribed to architects, worked together to make this policy position the only acceptable one. We don’t know what the long-term effects of the Grenfell Fire, or the ban on combustible claddings, will be; in particular, a reduced ability to high-performance insulants, particularly in a high-rise retro-fit context, raises challenges in terms of our ability to meet reductions in energy consumption. Nonetheless, what we do know at this stage is that the Grenfell Fire has tested our confidence in testing, revealing the divergence between tests and reality. It has also tested the current drive to de-regulate, and at least temporarily strengthened an association between architects and prescriptive standards.

Liam Ross is an architect and senior lecturer in Architectural Design at the University of Edinburgh. He was commissioned to exhibit material at the British Pavilion at the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale, and is currently working on a monograph – Pyrotechnic Cities: Architecture, Fire Safety and Standardisation, Routledge, 2022; this text is part of it.

The Writings on the Wall is an editorial project developed in collaboration by Volume and Beta – Timișoara Architecture Biennial, about the capacity of loopholes to create exceptional experiences among the laws that produce our urban spaces.

‘Grenfell Resident Who Raised Fire Concerns Labelled Troublemaker, Inquiry Told’, The Guardian, 21 April 2021, http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/apr/21/grenfell-resident-who-raised-fire-concerns-labelled-troublemaker-inquiry-told.

Judith Hackitt, Building a Safer Future: Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2018), www.gov.uk/government/publications. p. 14.

‘Grenfell Tower Fire Review Branded “Betrayal and Whitewash”’, accessed 27 July 2018, https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/grenfell-tower-review-branded-betrayal-and-whitewash/.

‘“Radical Reform” of Building Regulatory System Needed, Finds Dame Judith Hackitt – GOV.UK’, accessed 26 July 2018, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/radical-reform-of-building-regulatory-system-needed-finds-dame-judith-hackitt.

Hackitt is the former director of the Energy Saving Trust, a body which publishes a list of “approved products” that “meet UK regulatory requirements”. This list includes polyisocyanurate foam insulation boards similar to those used on the Grenfell tower refurbishment. For concern over Hackitt’s appointment, see Robert Booth, ‘Grenfell-Style Cladding Could Be Banned on Tower Blocks, Government Says’, The Guardian, 17 May 2018, sec. UK news, http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/may/17/grenfell-style-cladding-could-be-banned-on-tower-blocks-government-says.

Hackitt traces this principle back to the Health and Safety at Work act, of 1974: “The principle of risk being owned and managed by those who create it was enshrined in the UK health and safety law in the 1970s, following the review conducted by Lord Robens, and its effectiveness is clear and demonstrable”. See Judith Hackitt, ‘Building a Safer Future: Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report’ (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2018). p. 6. www.gov.uk/government/publications.

Hackitt, ‘Building a Safer Future: Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report’. p. 6.

Colin Todd’s expert witness report casts some doubt on this association between tall buildings and fire risk; indeed, it clearly states that “High Rise does not mean High Risk”. The incidence of mortality in high-rise buildings, due to fire, is not higher than those in other forms of accommodation. If there are greater “risks” within this particular kind of building – centralised, tall accommodation for social tenants – they are political, rather than technical. That is, I think it is possible to say that Hackitt here follows, and legally reinforces, a popular concern about high-rise social housing, one which has been reinforced – even in “progressive” discourse – through Grenfell. As evidence we might cite Simon Jenkins column in the Guardian, which has used Grenfell to claim that high-rise residential buildings “are antisocial, high-maintenance, disempowering, unnecessary, mostly ugly, and they can never be truly safe”. Ironically, The Grenfell Enquiry reports allow us to prove that this last assertion, at least, is false. Andrew O’Hagan perhaps betrays a similar trajectory; his extensive article on Grenfell, for the London Review of Books, is titled “Tower”, and notes an association between tall buildings and Heaven. That is, one likely consequence of Grenfell will be an increased social and political concern about the real and perceived risks of high-rise accommodation, a concern which architects might well help to shape. See Colin Todd, ‘Report for The Grenfell Tower Inquiry: LEGISLATION, GUIDANCE AND ENFORCING AUTHORITIES RELEVANT TO FIRE SAFETY MEASURES AT GRENFELL TOWER’, 2018. p. 15. Also ‘The Lesson from Grenfell Is Simple: Stop Building Residential Towers | Simon Jenkins | Opinion | The Guardian’, accessed 29 June 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/15/lessons-grenfell-tower-safer-cladding-tower-blocks. Also ‘Andrew O’Hagan The Tower LRB 7 June 2018’, accessed 25 July 2018, https://www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n11/andrew-ohagan/the-tower.

Hackitt, ‘Building a Safer Future: Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report’. p. 3.

Luke Bisby, ‘Professor Luke Bisby’s Expert Report, Grenfell Tower Inquiry’, accessed 27 June 2018, https://www.grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk/evidence/professor-luke-bisbys-expert-report. pp. 2–3.

Bisby, ‘Professor Luke Bisby’s Expert Report, Grenfell Tower Inquiry’. p. 2.

Thermally “thin” materials are those that respond to pyrolysis quickly, and so ignite easily, having either high conductivity or low heat capacity. It is conventional to use this term to describe the pyrotechnic behaviour of individual materials, but this can be misleading. As we will see below, it is possible to construe ACM cladding as relatively “thick”, in the sense that aluminium does not readily ignite. Rather, I suggest here that we can think of whole assemblies as thermally “thick” or “thin”, and that this provides a useful way – for instance – to understand why the Grenfell refurbishment burned down, and the original tower did not. See Bisby. p. 15.

Hackitt, Building a Safer Future: Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, n.d.), www.gov.uk/government/publications. p. 2.

Torero. p. 3.

‘Hammond: Grenfell Cladding Was Banned in UK’, BBC News, accessed 4 July 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-politics-40318318/chancellor-philip-hammond-says-grenfell-cladding-was-banned-in-uk.

Robert Booth, ‘Grenfell Tower: 16 Council Inspections Failed to Stop Use of Flammable Cladding’, The Guardian, 21 June 2017, sec. UK news, http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jun/21/grenfell-tower-16-council-inspections-failed-to-stop-use-of-flammable-cladding.

‘Grenfell Tower Fire Probe Focuses on Cladding | Construction Enquirer’, accessed 27 July 2018, https://www.constructionenquirer.com/2017/06/15/grenfell-tower-fire-probe-focuses-on-cladding/.

Booth, ‘Grenfell Tower’.

Department of Communities and Local Government, Approved Document B: Fire Safety, Volume 1 Dwellinghouses, 2013 edition (Place of Publication Not Identified: National Building Specification, 2013).

Here I am quoting from evidence given by Tony Enright, a fire safety engineer, cited by Inside Housing in their analysis of the Grenfell Tower “Paper Trail”. See Inside Housing.

‘“Flaw in Industry’s Thinking on Panels”’, Inside Housing, accessed 4 July 2018, https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/news/flaw-in-industrys-thinking-on-panels–51019.

In the review of regulatory failings I am providing here, I draw heavily on existing and excellent media coverage. Outstanding among this was the coverage offered by Inside Housing. It is in their coverage that the DCLG memo quoted from here was unearthed. See Inside Housing, ‘The Paper Trail: The Failure of Building Regulations’, Shorthand, accessed 4 July 2018, https://social.shorthand.com/insidehousing/3CWytp9tQj/the-paper-trail-the-failure-of-building-regulations.

‘Expert Panel Recommends Further Tests on Cladding and Insulation’, GOV.UK, accessed 4 June 2018, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/expert-panel-recommends-further-tests-on-cladding-and-insulation.

‘Statement Regarding Celotex BS8414 Cladding Tests’, BRE Group (blog), 31 January 2018, https://bregroup.com/press-releases/celotex-statement/.

‘Scale of Fire Safety Testing Failures Laid Bare ABI’, accessed 4 June 2018, https://www.abi.org.uk/news/news-articles/2018/04/scale-of-fire-safety-testing-failures-laid-bare/.

Robert Booth, ‘Cladding Tests after Grenfell Tower Fire “Utterly Inadequate”’, The Guardian, 24 April 2018, sec. UK news, http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/apr/25/cladding-tests-after-grenfell-tower-fire-inadequate-claims-insures-report.

Tom Lowe, 19 February 2021, ‘Grenfell Inquiry Round-up: What We Learnt from Arconic This Week’, Building, accessed 1 September 2021, https://www.building.co.uk/news/grenfell-inquiry-round-up-what-we-learnt-from-arconic-this-week/5110521.article.

Angus Law and Graham Spinardi, ‘Performing Expertise in Building Regulation: “Codespeak” and Fire Safety Experts’, Minerva, 26 May 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-021-09446-5.

The preparatory research for this section was developed in parallel to engaging with two forums for such discussion. The first was the Holyrood Magazine ‘Building Regulations in Scotland – Ensuring People’s Safety’ event. The second was a cross-party group on architecture and the built environment, held at the Scottish Parliament, on September 21st, 2017. In both events, which involved contributions from engineers, architects, regulators, fire-safety experts, manufacturers, and clients, it was notable how each stakeholders understood Grenfell from a sectoral perspective. For architects, Grenfell was seen as the result of the lack of authority architects currently held; it was only by re-establishing a singular point of authority within building design that such errors could be prevented. On the other hand, fire safety engineers typically used the event to call for further professionalization and reinforcement of their own position as experts, seeking to extend that role to encompass oversight of all matters of design. These meetings, in themselves, demonstrated how powerful a “boundary object” fire is, and how many different stakeholders seek to enrol it into their own concerns.