Editorial Volume 57: Mind the Gap

In Volume 56: Playbor, we introduced the theme of ‘work and play’ referring to a famous scene in Stanley Kubrick’s movie The Shining in which the wife discovers, next to a typewriter, a pile of A4s produced by her husband. All the pages are completely filled with one single line repeated over and over again: “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”. This is before the copy-paste era, I have to add – we’re talking the age of the typewriter here – so hand-typed from the first to the very last letter.

The scene illustrates an argument for the introduction of play in the working environment, more specifically on the level of the worker. Simple boring tasks tend to slow the worker down. It’s hard to maintain concentration and thus productivity at a high level throughout the day. Only a madman would be able to do so. Stimulation in the form of elements of play could be an option to counter this tendency. The Playbor issue focused on the up- and downsides of this development of ‘playful interaction’ and on the potential consequences for spatial design.

If play and control were the elements explored in Volume 56, Volume 57 could be dedicated to the opposite: boredom. We thought, 56 and 57 could be complimentary issues and maybe the new theme shouldn’t be boredom itself but the tedious components in spatial processes that therefore receive less attention. That’s how ‘the boring issue’ started.

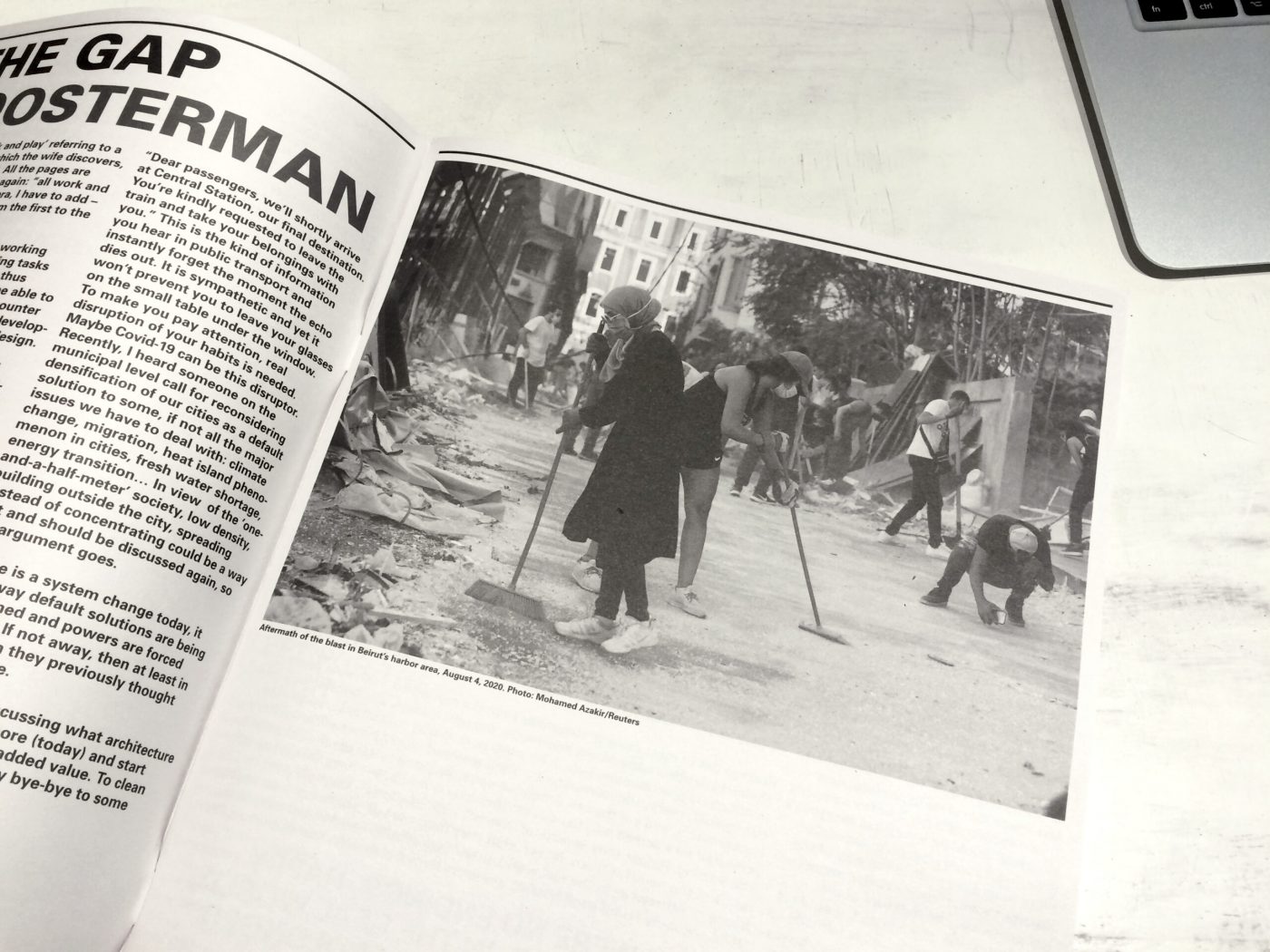

And then Covid-19 knocked on the door. Or rather, it took us by surprise globally, an invisible tsunami but just as devastating. This was clearly not the right moment to discuss boring issues, no matter how important, interesting, and even urgent they may be. When the house is on fire, in-depth reflection is not the first thing to call for. So, we shifted our attention.

Covid-19 triggered a whole army of visionaries we weren’t aware of to predict a system change, a revolution of sorts. Not for the first time, though. In the aftermath of the financial and banking crisis of 2008, we also heard a lot that ‘the world had changed fundamentally’, that old times wouldn’t return. They didn’t, but they did. Some tweaks and adjustments to the financial system, and that’s about it. The powers that be are still the powers that be; the old regime hasn’t truly vacated the scene. At Volume, we did see some changes in the way architecture is being produced though. Less focus on ‘icons’, a bit more on intelligently working with the people that actually use buildings and that should be the reason for a project to come into being. More attention to small communities, to inclusion, to impact and agency, to materials, to circularity, to energy and more. All themes that were discussed before Covid-19 brought our economies to a halt, but somehow the new situation created a renewed awareness of their importance.

“Dear passengers, we’ll shortly arrive at Central Station, our final destination. You’re kindly requested to leave the train and take your belongings with you.” This is the kind of information you hear in public transport and instantly forget the moment the echo dies out. It is sympathetic and yet it won’t prevent you to leave your glasses on the small table under the window. To make you pay attention, real disruption of your habits is needed. Maybe Covid-19 can be this disruptor. Recently, I heard someone on the municipal level call for reconsidering densification of our cities as a default solution to some, if not all the major issues we have to deal with: climate change, migration, heat island phenomenon in cities, fresh water shortage, energy transition… In view of the ‘one-and-a-half-meter’ society, low density, building outside the city, spreading instead of concentrating could be a way out and should be discussed again, so the argument goes.

If there is a system change today, it is the way default solutions are being questioned and powers are forced to move. If not away, then at least in a direction they previously thought unthinkable.

Let’s stop discussing what architecture can’t do anymore (today) and start looking for its added value. To clean the slate, we say bye-bye to some of its defaults.