Brendan Cormier, Lead Curator of 20th and 21st Century Design for the Shekou Partnership at Victoria and Albert Museum and former managing editor at Volume, has picked a head-to-head between Rem Koolhaas and Larry Beasley that was published in Volume #23 Al Manakh Gulf Continued.

“Of course, it’s impossible to say which contribution sticks out the most for me. My gateway drug was Volume #24, Content Management. My roommate had stolen a copy of it from The Berlage, and I was totally drawn into Alejandro Zaera-Polo’s Politics of the Envelope mega-essay. But I think more importantly, it was the first time I read a magazine that had a coherent thesis explored throughout the issue (notably, with exception of Zaera-Polo’s essay), and that it offered a different and original lens with which to view architecture: the architect as content manager.

I think for the website I’d highlight an interview. Interviews in Volume always seem a bit more casual on the one hand, and focused on the other, which makes for interesting revelations. One of my favorites is the head-to-head between Rem Koolhaas and Larry Beasley. Koolhaas really interrogates Beasley on his commitment to his work in the Middle East, and the decision-making rationale behind his consultancy practice, highlighting some of the bigger problems of international consultancy work. The interview is all the more exciting, knowing that Koolhaas is towing a dangerously similar line in his own consultancy work, and it’s interesting to see how he stakes out a different position and attitude behind his work to legitimate it vis-à-vis the work of Beasley.”

Larry Beasley, former co-director of planning for the City of Vancouver and currently the special advisor to the Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council, gives the history behind the UPC and makes the case for how the transformation of Vancouver can provide some answers to addressing Abu Dhabi’s current state. John Madden, senior planning manager of development review and urban design, also contributes to the discussion.

Rem Koolhaas: Are you based here?

Larry Beasley: No, I’m based in Vancouver.

RK How often are you here?

LB Once a month. Usually for five to seven days at a time.

RK So how did you arrive in Abu Dhabi?

LB Going back to before I came into the equation, there were a couple of things that started happening at the same time here in Abu Dhabi. As you know, when Sheikh Zayed passed away and the new leadership came in, they decided to open land up for private development and private ownership, similar to what had happened in Dubai a few years earlier. Very soon after that, they saw an array of development proposals. None of the proposals really considered the other ones. I’ll give you an example. There were five city centers that were proposed at one time. The amount of development was dramatically above what even the most optimistic measure of growth could have sustained. They were headed into a situation where they could see the same thing happening, which has happened in Dubai. So, Dubai is beginning to deflate. Let’s hope that that’s its current state is not its future, but anyway, that happened.

Secondly, a number of people in the leadership advising His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan began to realize that Abu Dhabi’s environment and society were being demeaned.

RK You are talking about how long ago?

LB This thinking started about three years ago. That led six months later to the Executive Affairs Authority, which is the government arm of Sheikh Mohammed, to review cities around the world that were doing positive things toward the livability of their cities. They identified Vancouver as one of their cities. You know that Vancouver scores high on many measures in livability.

RK Why do you think that Anglo-Saxon cities always emerge at the top of these kinds of lists? I’m sometimes baffled, because I would consider Rome to be a livable city, but in this region you get Vancouver and Adelaide. Could it be that the advising consultants are from those cities?

LB I’m not saying that I believe in these things, but that is the reality. Let me be cynical for a moment. A society decides that it wants an art gallery, so it buys the Louvre. This is a society that often … I say this respectfully to my colleagues … wants to buy retail. And they want to get ahead that way. So, maybe they didn’t look deeply into the potentialities but they did look around at cities in the world. They had some indicators, and they concluded that Vancouver was one of those places. And as they did research, they came up with my name because I was Vancouver’s Director of Planning, along with a colleague. It so happens that I was retiring at that point. So they approached me. They wanted me to come here and start planning.

RK Who was it exactly?

LB Agents of Sheikh Mohammed, including Falah Al Ahbabi, who is now general manager of the Urban Planning Council. They came to me, and all they said was: would you do a master plan for our city and come and live here and do that. I said no, I could not come and live here. Second, I didn’t think that doing a master plan was the right thing to do because plans are done by consultants, and then they sit on the shelf. I told them two things. First, they needed to put together a planning organization with a lot of expertise and build a culture of planning in the emirate. Second, I suggested to deal with the problem of all of these huge developments. [To deal with the latter] we could do a strategic plan in a short amount of time. You’ve probably seen the plans. They’re very different from most other strategic plans because they also have an urban design component. Most strategic plans don’t. But my philosophy is that we have to get back to designing cities. We haven’t often been doing that recently.

RK You designed a council as an organization? This is your blueprint…

LB Yes. It was my idea to create an agency but we conceptualized what we thought would be a good, functioning agency, and what would be its components, what would be its philosophy, what would be its emphases. We put it together; it was proclaimed; it was created just over a year ago, and it now has about 110 staff or so.

RK Does this blueprint reflect the one that was in place in Vancouver?

LB I do not believe in importing something from one place to another place.

RK So to what extent do they differ?

LB What I think is important are some underlying principles, both underlying principles of organization and the underlying principles of urbanism … and merging the underlying principles with the traditions and the philosophy of the place.

RK Before you came, had you ever lived abroad?

LB I’ve been many places.

RK No, I meant actually living. So how long did it take you to grasp the issues here?

LB I’m still grasping them. I’m still learning.

RK When you first came here, did you actually live here?

LB No I’ve never lived here.

RK So, you didn’t have an initial three months or so…

LB No, I came here for extended periods but I never lived here. To me it was more important, rather than for me to suck it all up and play it all back, to organize people to do it for themselves. And so, the way that we’ve been planning is that we bring in really fascinating outsiders and put them together with really fascinating locals, and we try to merge the local traditions with new principles because frankly, this is not a society with a history of urbanism. These are Bedouin people really. Most of what has been imported from, say, the 70s on has not been helpful to them.

RK It has been nightmarishly simple and exploitative. Of the current organization …what percentage is from your world? What percentage is local?

LB I think about a third is local now. Our objective is to find a state of grace here within a few years, where all of the planning organization will be local. But you have to understand that there’s not a deep capacity here. So we’ve been out training. We’ve been training people in the development industry and things like that to try and build that capacity. We’ve been talking about curriculum in schools. But the fact is, what I really like is that there has been a corporate objective to bring young people from kindred fields and they’re learning on the job. And I can tell you that they’re incredible. They want to figure out how to build their city to be livable and hospitable and environmentally sustainable.

RK Were you initially invited to look at all of the emirates?

LB I was invited only to look at the Emirate of Abu Dhabi… the whole emirate. So, this was an initiative by the leadership here in Abu Dhabi. Dubai has its own initiative; Sharjah has its own initiatives. I believe that the leadership here did believe that by modeling a different way of doing some things, that it would start to be influential [to other emirates’ planning efforts].

RK Have you seen the signs of that?

LB Oh yeah. I’ve seen other emirates talking about doing urban plans and putting development management systems in place. But it’s still too early. Even if some things happen faster here than in most other parts of the world, the philosophy that we’ve all been aspiring to has just started to be built, but it’s not there yet.

RK How are you judging the transition from the ideal to the practical? How did you conceive that you could ever force the substance of what is typically generated here into this framework?

LB I believed in the seriousness of the leadership. I believed that if we proposed things that were rational and spoke to their concerns, and that we understood that their concerns went beyond the economics of the moment, that they would endorse them. And in this culture, when the leadership endorses something, then magical things happen … unlike my culture. It’s not that way in my culture.

RK Is it possible to see any of the plans you have been revising? (1)

LB As a matter of fact, we’re working on befores and afters. There is a lot still not happening right away. If you see Al Reem Island, for example, I don’t think it’s the right way. It’s not ultimately the way the emirate should go. But it has had a dramatic transformation.

RK What we are particularly interested in is what happens if you impose this kind of structure, and to what extent and in what way it grows.

LB Yes. I want to emphasize another thing though, and that is that, in no way, shape or form do I believe that anyone should import anything. I think there is a growing knowledge about some underlying principles for cities. People are trying to share and experiment around the world, and they should be a part of that. But I think that it has to be different here, and I’m afraid that it’s not very different. It isn’t differentiated. Ironically, some of the most tangible examples of placeness decided by Sheikh Zayed.

RK Yes, that’s what we also discovered, that the early thinking was actually very forward thinking. And then, in a way, the plot was lost.

TR Do you have theory for what happened?

LB In my opinion, it changed when Sheikh Zayed passed away. Sheikh Zayed was personally involved with a lot going on in. And he had a vision about it. You can say you like it or you don’t like it but it was a coherent vision over many years. At the same time, he was building a country from nothing, securing his natural resources against exploitation by outsiders. The new leadership has all of that, but what happened when it opened up for private land ownership and development is that everyone started bringing everything here. My anxiety is that cities like Abu Dhabi and Dubai … they end up getting things dumped into them.

RK To what extent is UPC based on your organization in Vancouver, in terms of people?

LB A few people here were in my organization – four. We’re all Canadians.

I’ll tell you another story which interests me … I went and talked to literally hundreds of people – people who ran companies, all kinds of people. And people would always tell me one story, which is about growth and the economic development. And always before I would leave, and usually with a lot of humility, they would then tell me a second story, which had to do with their families, that families are being pulled apart, about not having access to water. Sheikh Zayed was kind of like the custodian of all the public interests. He could make sure that the waters were protected, and that was happening – while there was still a growing economy. But, you know, the current leadership … I think that they were very smart to try to do something about it because they were being asked to manage the same way but on a huge scale, and it’s just not possible. And so what was happening is that a lot was being lost – things that mattered to people. [looking at images]

RK How do you conduct the design review?

LB Through a series of workshops, community engagement. We have an example, where we engage with the Emirates Foundation about what the community needs, aspirations about activities… basketball courts, tennis courts, these kinds of things.

RK So, explain to us how it works – the process.

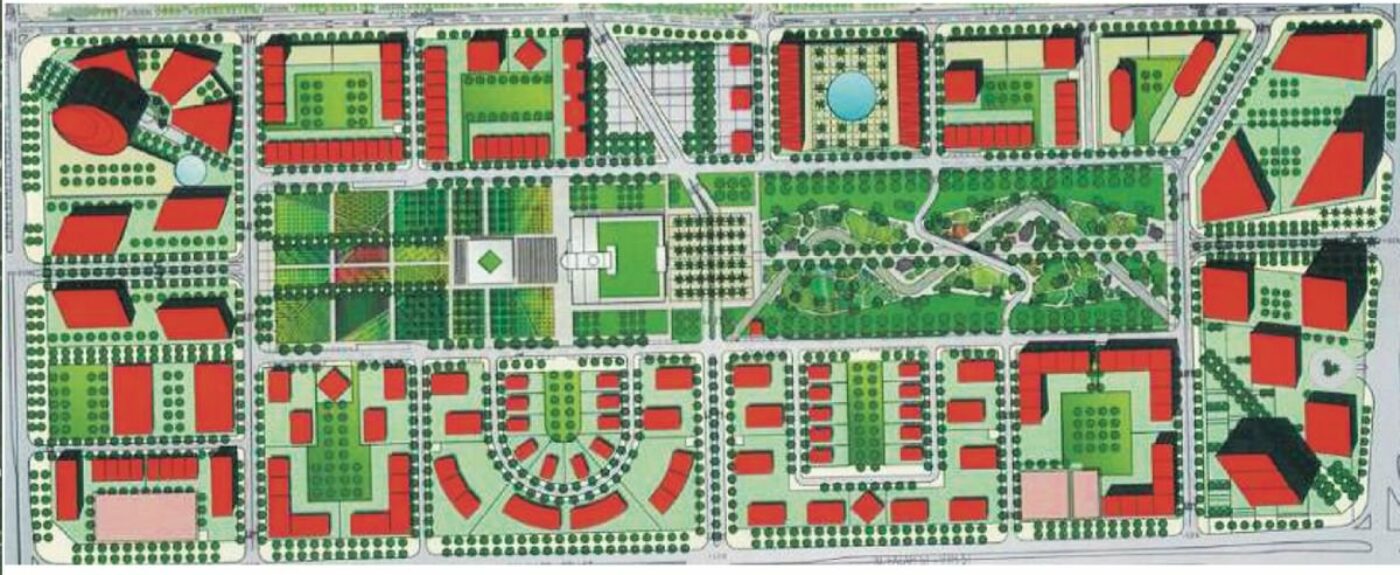

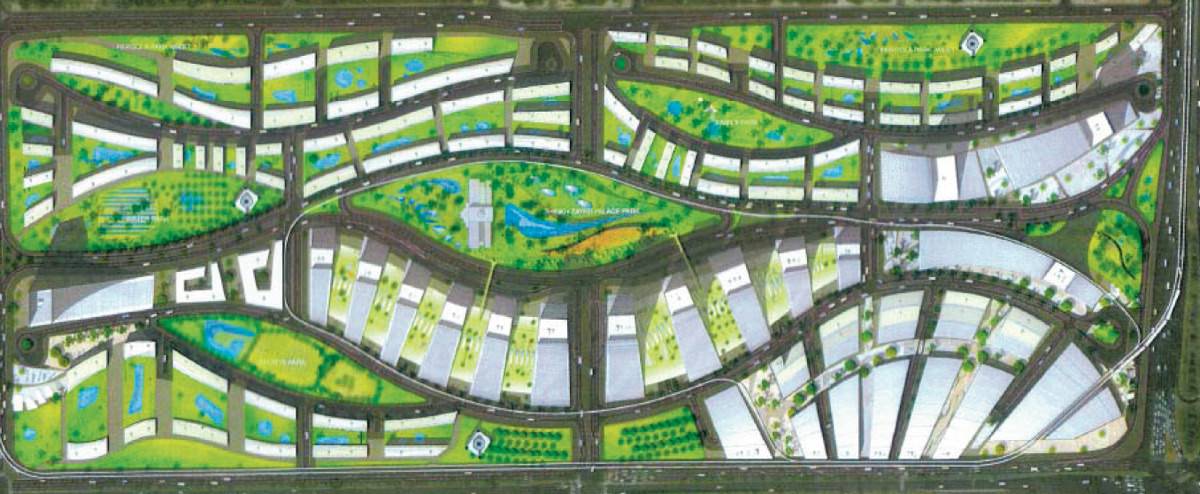

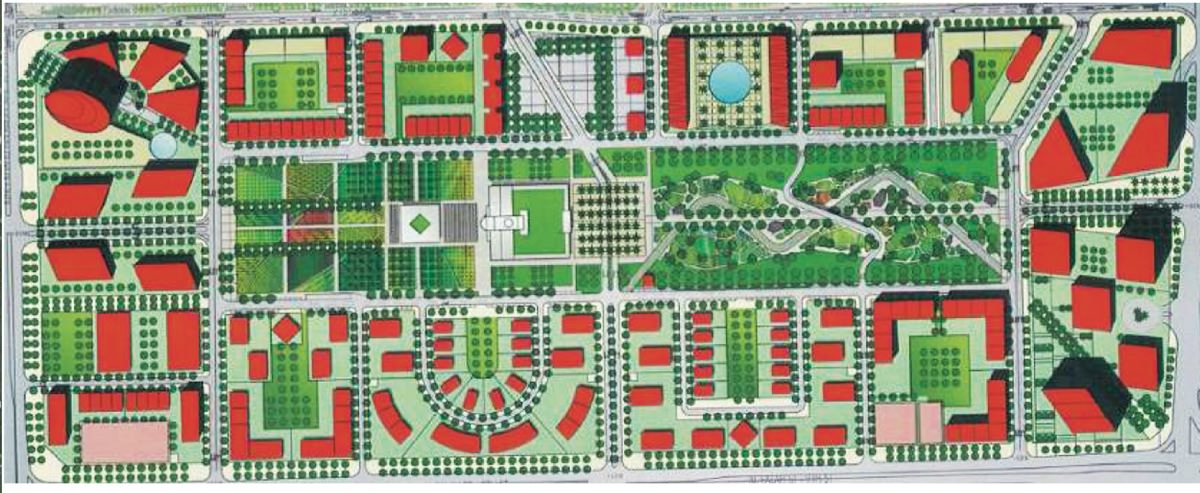

JM Often times, it’s what we receive, in terms of an application. When the organization was announced back in September of 2007, there was this tidal wave of anticipated development that was being funneled into the UPC. And the magnitude of the size of these projects is something that I’ve never experienced. I don’t think that anyone in the world has experienced the scale and magnitude of these things. And in September 2007, we were essentially five people. And there were nine major government developers that were proposing communities of 350,000 people. So the quality of the submissions really varied, but by and large they were so used to just presenting a couple pieces of paper to the leadership. It’s always looking at the buildings and what they look like from the sky, from a bird’s eye point of view. We really wanted to change that and put some rigor into how we experience cities … how the Emiratis experience them. We were getting plans that had no response to the context. It was just simply a development, and it was more about the identity and picture that it portrayed from the sky, whether it was the shape of a falcon, a flower, an amoeba, or whatever. We had one that was the shape of a Persian carpet, because they said that was indigenous. And people talking about green space here and calling them oases, not understanding that the oasis is an agricultural invention.

So this is a before and after example: Mid-island. This is the mangrove area on the other side. This is a proposal for a college, a higher college of technology. This is what they came forward with, in terms of their proposal. Again, it was about the iconography. They didn’t understand what they wanted. They didn’t even know how much program they wanted. They just wanted something different, and that’s all they wanted. So they came forward with this. And we asked them, what is it that you want to program there?

RK And the after image is of the same architect?

JM Yes.

RK So, in between there were conversations with you.

JM Yes, quite a few.

RK How long did this process take?

JM With this one, things happened very quickly. This was a process that took about three months.

RK And did they also reduce the program?

JM Yes, by what percentage I can’t say exactly. But we asked them a question – what is it that you’re in charge of? What’s your mandate? Well, they said providing higher education. So, we tried to keep them to that program.

RK To what extent did you influence not only decreasing of program but also the shapes?

JM To a large degree. I mean, we’re not dictating what the design should be, but we’re trying to suggest…

RK What do you do? Do you sketch or do you…?

LB We have an in-house urban design studio. It’s not a big group – about four or five people but they do a lot of sketching. But I have to tell you the [project] architect still drives the architecture. We don’t lay a trip on the architects.

RK Here, you went from a rectangle to an oval, and here you went from an oval to a rectangle.

JM Yeah. This is an interesting site. When we talked about the importance of understanding heritage and culture and aspirations for future generations, this palace was the home of Sheikh Zayed. This is right in the heart of the downtown. Basically, the development was turning its back on the rest of the city. The palace gets lost completely. There is no respect for it as a place, as an important historic feature within the city. So what we wanted to do is give it some breathing room, to protect it as a place, an important icon in the city.

RK And here, did you reduce the program?

JM Very much so, probably by 30 to 40%.

LB You’re going to find in almost every project that the program got reduced, because all of the programs were over.

TR Is 30 to 40% an average number, would you say?

LB I’d say 30% is an average.

JM Each project is trying to maximize its own individual profit on a particular site. But sometimes they are so focused on what that one site is, in terms of maximizing profit, that it might be the exact same program two blocks down the road. So what we’re trying give a of lay of the land. This is an example of a program that was overextended – Sheikh Zayed Stadium, an historic and iconic piece of architecture. There was a plan to demolish it and relocate the function to this new stadium. The only thing that was driving it was: it’s gotta be bigger than Dubai’s stadium. First of all, they were saying 65,000 capacity. This older one can hold 70,000 but they didn’t want to let that out of the bag.

The form of development is these towers in a park with lush landscaping. We’re saying, this isn’t Singapore. It doesn’t rain here. So, we’re beginning to look at a form of development that has more site coverage and thinking about a landscape that is more indigenous, in terms of using less resources.

RK Did you have any success there because that is one of the trickiest things to achieve… because the indigenous, in everyone’s eyes, simply looks poor and imperfect and barren.

LB Well, you see the second issue out here is that there is a tradition that ownership is established through planting. So, literally, if you go along the roads here, they’re all planted because that establishes ownership. Even the perimeter of the entire emirate is planted.

Notes

1. The question refers to plans by private developers which are under review at UPC’s offices.