The Radical Pedagogies Project

The exhibition ‘Radical Pedagogies: Reconstructing Architectural Education’ will be presented at the 7th WARSAW UNDER CONSTRUCTION FESTIVAL from October 12 – November 10. This is the third edition of the ‘Radical Pedagogies’ exhibition, following the 3rd Lisbon Architecture Triennale (2013) and, most recently, the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture, curated by Rem Koolhaas (2014), where it was awarded a Special Mention. A 32-page dossier of the project was published by Archis to accompany the exhibition, and is featured as an insert in Volume #45: Learning.

In a remarkable photograph of May 1968, Giancarlo de Carlo is in a vigorous debate with the students taking over the Milan Triennale in protest. He leans forward, angry but listening intently as a student lectures him. Both sides, the teacher and the students surrounding him, are radicals. Despite his jacket and tie, Giancarlo de Carlo is a self-professed anarchist and the students are paradoxically following his call to question institutional authority by refusing to follow him. The whole ecology of architectural education is destabilized, twisting restlessly around itself in a kind of vortex. The circle of students has become a classroom – a portable, improvised space in which the streets become the real teacher. The line between urban life and education has dissolved. Protest has become pedagogy.

In the 2010 protests against the latest university reforms promoted by Italian Minister of Culture Maristella Gelmini, students marched on the streets of Rome. In a performative political act, they took over the public space of the city with shields reproducing covers of seminal books. The scene captures the intersection of protest, education and Italian design, with the brightly colored shields lined up as a visual manifesto. Rather than addressing the content of the protest, the Minister Culture responded: “Do not let professors manipulate your opinions.” Active political engagement was suddenly reduced to a faded replica of 1968, instigated by now tenured radicals. The scene in the streets was treated as just a classroom exercise. Pedagogy has become protest.

The Radical Pedagogies project goes beyond mere replica or nostalgia to investigate the entanglements between architecture pedagogy and political protest. It is itself a pedagogic exercise, a political project, and the securing of a space for design, thought and action. Radical Pedagogies is an ongoing multi-year collaborative research project led by Beatriz Colomina with a team of PhD students of the School of Architecture at Princeton University. It has so far involved three years of seminars, interviews, archival research, guest lectures, and more than 90 case study contributions by over 78 protagonists and scholars around the world. (1) It culminated in a major installation at the exhibition at the Venice Biennale of 2014, where it was awarded a Special Mention. (2) In this, and similar research projects conducted by the PhD program at Princeton, architecture history and theory are taught and practiced as an experiment in and of themselves, exploring the potential for collaboration – in what is often taught to be a field of individual endeavor.

Architecture pedagogy has always been a political act. It has never merely been a space of reflection, of training and rehearsal, but one of action, reaction and interaction. To teach architecture and its history is to preserve and reopen those sites, to question pedagogical conventions and challenge the political status quo.

Radical Pedagogies explores a series of intense but short-lived experiments in architectural education that profoundly transformed the landscape, methods and politics of the discipline in the post-WWII years. In fact, these experiments can be understood as radical architectural practices in their own right. Radical pedagogies shook foundations and disturbed assumptions rather than reinforce and disseminate them. Defiantly questioning the dominant modes of architectural education of both the Polytechnique and the Beaux Arts systems, they rejected and reshaped the field of architecture. At the same time these experiments became tools for political destabilization or alternative models of collectivity. Progressive pedagogical initiatives aimed to redefine architecture’s inherited relation to social, political, and economic processes and sometimes culminated in radical upheavals that clashed with the inertia of ‘traditional’ institutions.

This was a period of collective defiance against the authority of institutional, bureaucratic, and capitalist structures. The world as it was known underwent drastic transformations on all scales – from the geopolitical landscape to the materials populating the new domestic environments – and utopian technological prophecies now manifested in a brave new world of computation, gadgets and spaceships. Architecture was not impervious to such shifts. Highly self-conscious, the architectural radicalism of this era exposed the anxieties about the discipline’s identity in a transformed world. A new generation refused to take architecture or its training as granted. They constructed a new space for redefinition of the discipline, launching a series of pedagogical experiments that shared a strong belief in architectural education as a tool towards political change.

Academic institutions became a space of confrontation – sites of extended intellectual, political, economic and physical battles. On the one hand institutions were understood as necessary hosts for the erosion of established structures of power. On the other hand they were perceived as mechanisms for the reproduction of existing systems of domination. Institutional authority was critiqued through a broad range of counter-institutions and alternative pedagogical platforms that undermined hierarchical structures.

The historical marker for this period of reconfigurations is often taken to be 1968, with the student revolts that took place around the world and the pedagogical transformations that surrounded them. While these revolts greatly exceeded the confines of architecture schools, architecture students were key in some of these protests. Central to the outcomes of these revolts, as they developed in Paris for example, was the formation in 1969 of the Unité Pédagogique d’Architecture No. 6 (UP6), which famously promoted an alternative to the pedagogy of the Beaux-Arts School. The UP6 openly accused the school’s prevailing curricula and teaching methods of being incapable of addressing architecture’s relationship to contemporary social and political maladies, and demanded that their vision of a new social order be reflected in the very basis of their studies. This demand was thought to concern not only the content of pedagogy, but also the mode of teaching and its institutional framework. In post-1968 Paris, architectural pedagogy was revised at the same time that the university was redefined. (3)

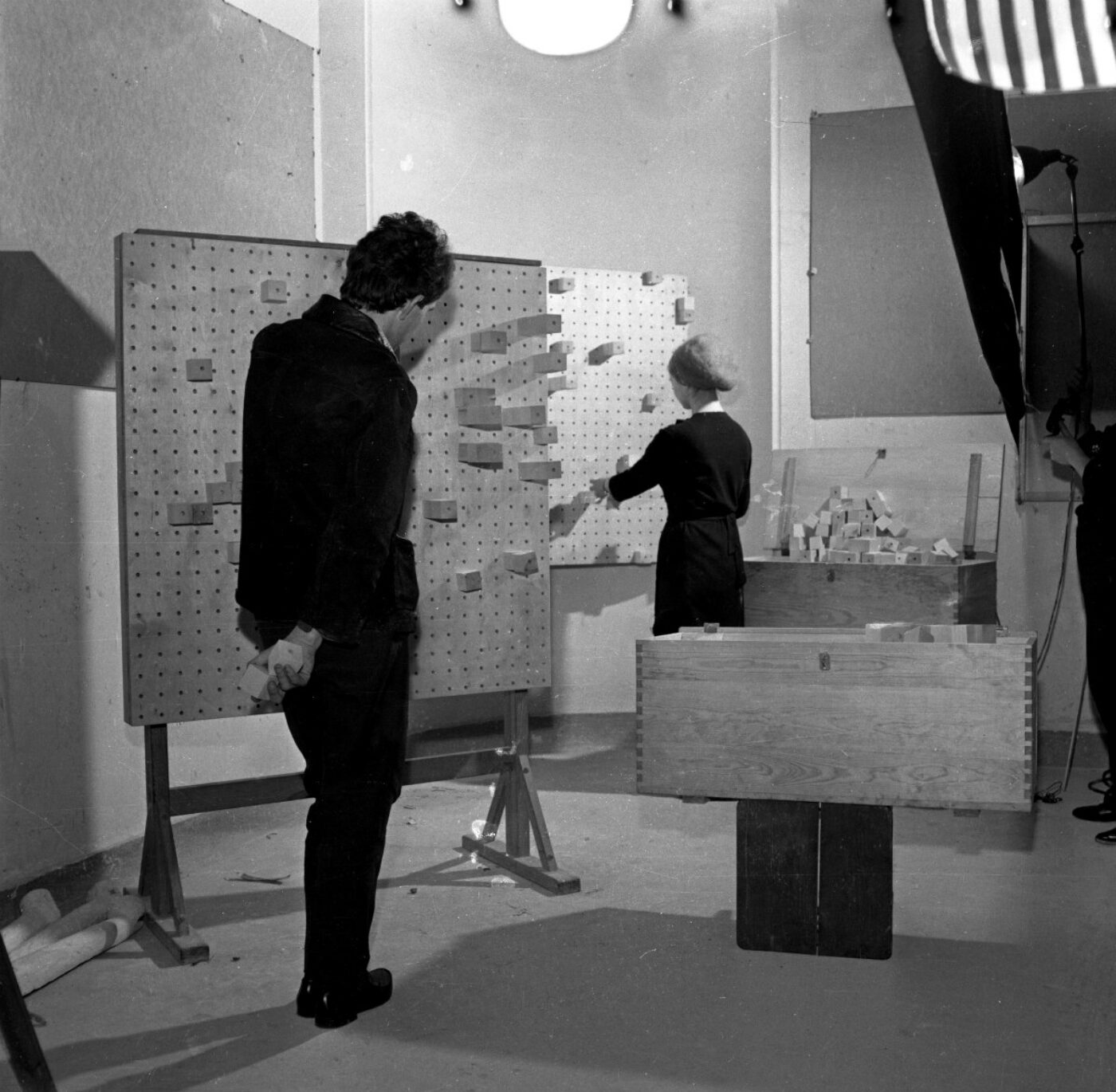

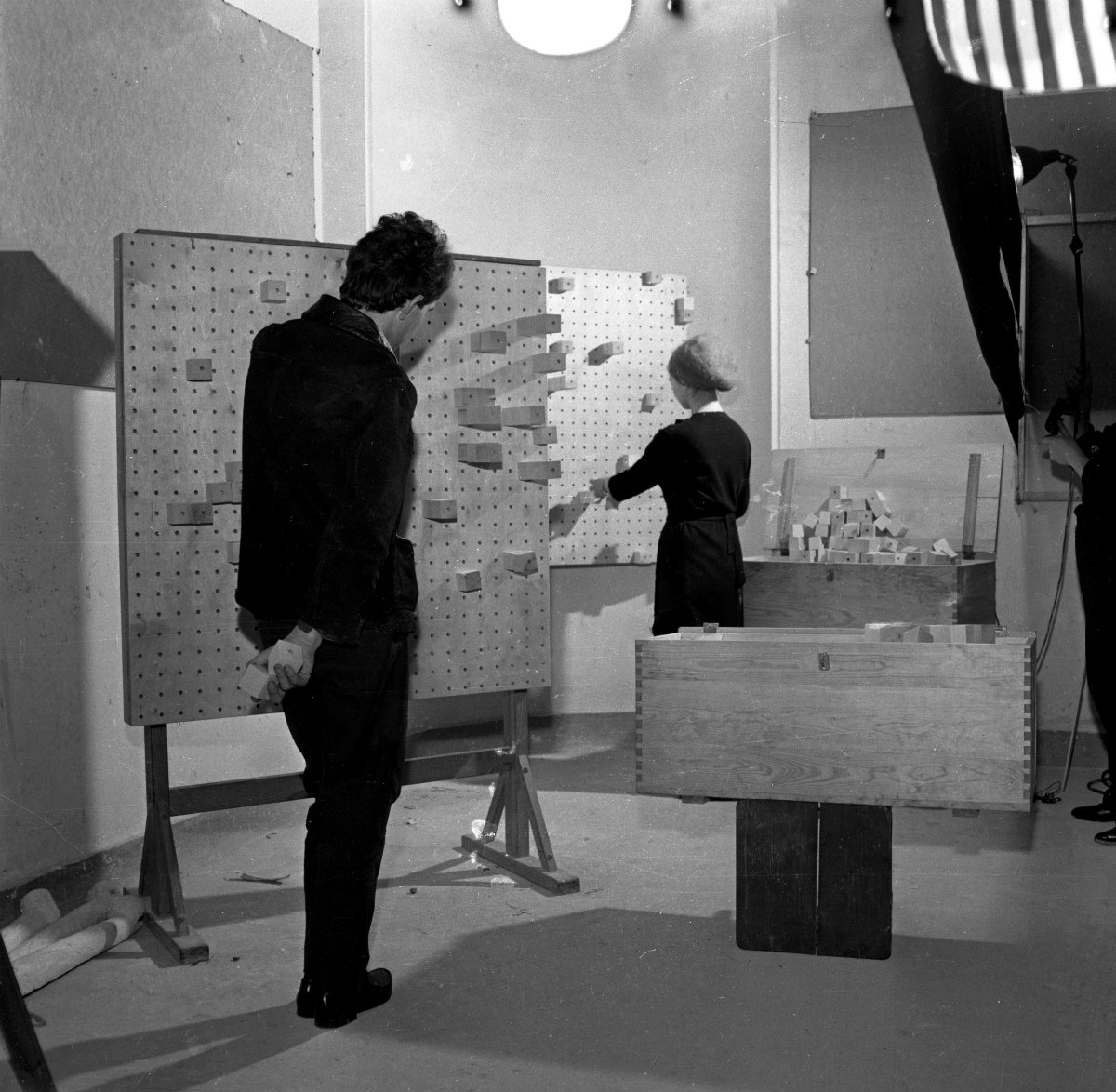

Yet some of the radical experiments aimed at a political reconfiguration of society prior to the 1968 revolts. The Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm, Germany, for example aimed to re-democratize Germany through design toward a ‘better society.’ (4) The school was founded in 1953 by, among others, Inge Scholl, sister of the Nazi resistance activists Sophie and Hans Scholl. Drawing on the functionalist-humanist legacy of the Bauhaus on the one hand, and cybernetics and process design on the other, the HfG was conceived of as site for institutionalized discourse and reinvention of the role of the designer. Architectural education was a deeply political project for its protagonists, one that provoked intense debates and diverse ideologies. The school finally closed its doors 1968 due to internal disagreements as well as a conservative government withdrawing funds. (5) Precisely the year of the student revolts across the Western world had become the endpoint for this experiment.

Radical experiments in architectural education went far beyond these well-known cases and were a truly global phenomenon whose reach extended beyond the geopolitical borders of Western world and democratic regimes, as defined during the Cold War. With the Institutional Revolutionary Party in power for several decades, for example, architectural education in Mexico during the 1970s had become increasingly disassociated from the country’s reality. As a response, faculty and students at the Escuela Nacional de Arquitectura took radical action by occupying parts of the school and proposing formed a new architectural curriculum for the school. Titled Autogobierno (Self-Government), this new curriculum was based on principles of self-management and open to student enrollment for almost four years. (6)

A series of upheavals led by students and faculty at the School of Architecture in Valparaíso, Chile in 1967, seemingly shared some similar concerns to those contemporaneously erupting worldwide. Yet rather than participating in any pursuit for political change, this particular experiment remained a radical pursuit for ‘a change of life’ through pedagogical practices that obliterated the boundaries between learning, working and living, rejecting any political emphasis to ‘change the world.’ (7) In fact, the activities of the School survived the tumultuous environment of the 1970s and 1980s in Chile by refusing to participate within it.

Simultaneously, the work of young socialist architects and urban planners exerted an allure on radical educators of democratic countries. That was the case of the Soviet group the New Element of Settlement (NER) – a group of Soviet architects that presented their work in the 1968 Milan Triennale after the invitation of Giancarlo De Carlo. Their book NER, On the Way to a New City (1966) was one of the most highly influential tomes that came out of the Soviet Union in the 1960s, primarily because of its critique of post-Stalinist Soviet planning practices. And it was through educators like de Carlo that NER’s rather audacious critique, along with their proposals towards a new spatiality of socialism, crossed the seemingly insular border of the Iron Curtain during the late 1960s. (8)

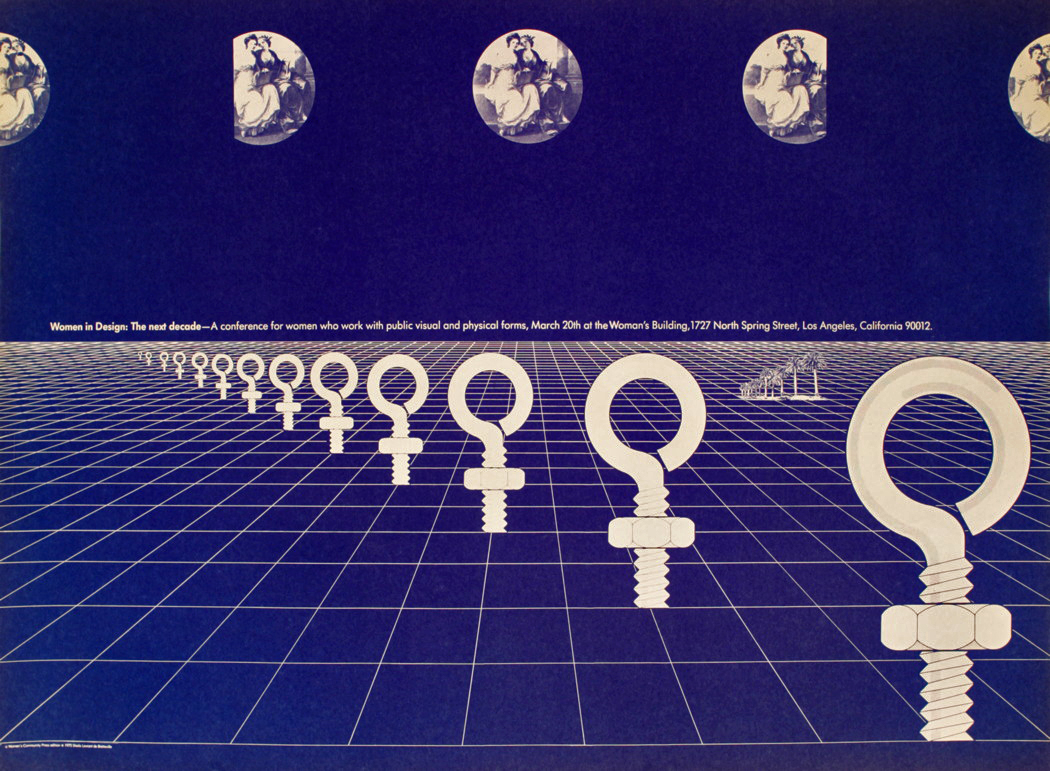

Within different experiments, radical pedagogical experiments introduced new constituencies within the discipline. The experimental summer programs of the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture, established in 1974, gathered different feminist sensibilities in the USA. Rather than merely opening a space for women within the profession, it rehearsed collaborative and non-hierarchical structures against the model of male-dominated institutions. (9) At UC Berkeley, the collaboration between the Center of Independent Living and the College of Environmental Design in the 1970s led to the introduction of physical accessibility as a topic of architectural education inside the classroom and the studio. (10) The ambition to give equal access to diversely abled bodies within the built environment was the spatial analog of a more general concern with the inclusion of ever-new voices and sensibilities within the University. In fact, this collaboration cannot be detached from the heated political debates, protests and strikes that were taking place on campus at the time, starting with the Free Speech movement in 1964. Political action took shape as a series of physical interventions on the Berkeley campus, such as curb cuts to form accessibility ramps. Policy changes that ensued these events, culminated into the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990.

As it becomes obvious from these examples, subversion took multiple forms: challenging programs, architecture schools, institutions and even the basic relationship between teacher and students. The diversity of pedagogical experiments was a crucial aspect of its radicality. Any sense of architecture as a singular, stable phenomenon was jettisoned by a kaleidoscopic array of challenges to conventional thinking, and in the diverse effects they triggered. Radical experiments in architectural education erupt with short-term appearances, yet they are connected as a web of shared concerns across ideologies and geographies. Rather than individuals creating radical schools or the genius figure instigating change, radical pedagogies are necessary formations of a larger political process sustained as a web of movements, a layering of short-lived, temporary manifestations.

The Warsaw experiment

The latest phase of the project is the exhibition Radical Pedagogies: Reconstructing Architectural Education, which will be part of the 7th Warsaw Under Construction Festival in Warsaw between October 9 and November 8, 2015. The exhibition adds a whole new layer of research, continuing the original mission of creating an ever expanding ‘open archive’ that encourages debate regarding the history and future of architectural pedagogy. Conceived as an interactive platform, the installation at the Warsaw Faculty of Architecture incorporates take-away texts, facsimiles, original publications and teaching documents, archival films, and implements interactive features through augmented reality.

The first two exhibitions of the project scratched the surface of the global dimension of architectural education, tracing the movements of students and educators – such as that of the Italian diaspora for the exhibition in the Venice Biennale – across an ever-shrinking world. For this occasion we have opened up new directions and a new density of global interconnections. Africa, East Asia, Australasia and Eastern Europe become the protagonists, opening new insights into pedagogical experimentation in the postwar years. The full counter-hegemonic force of radical pedagogy can be seen as people and ideas cross continents and political systems. The history of postwar architectural education has always been one of action, reaction and interaction. Narratives that have often advocated for a strictly linear dissemination of educational ideas from Western centers to global peripheries no longer hold water. The empire of classical design education convulses and cracks as every assumption is challenged.

This charting of experiments in architectural education across new regions did not arise from any desire to craft a ‘global history’ that includes the ‘non-West.’ Instead, it evolved organically as the project incorporated the invaluable input of an ever-expanding research team of educators, architects and students from around the world. Thus, we turn the spotlight on histories that are worth telling; multiple histories of architectural education whose groundbreaking dimensions can only be discerned and assessed vis-à-vis the context within which they unfold. But the new archive allows the resonances and dissonances between these experiments to be seen and discussed. The notion of radicality has acquired more and subtler hues.

The initial research team of PhD students at Princeton has grown exponentially to over 78 contributors from more than two dozen countries. The number of case-studies has likewise grown to over 90 and it will continue to grow in this extended collaborative project to build a new kind of archive of disruptive pedagogical practices that can act as a tool-box for students, teachers, designers and historians. The Radical Pedagogies project is carried out in the conviction that many of the radical experiments engaged with issues that have become again urgently relevant in today’s world. A number of the strategies are no longer disruptive and have been normalized as a part of educational research and design practice. But many of the experiments would still be considered controversial, if not highly disruptive today.

In an exercise of restraint we have selected just seventeen case studies for this insert of Volume. The vast majority of the material presented here comes from the new research to highlight six characteristic ‘threads’ that run through the expanded archive of the project: ‘Participative Educational Democracies’ presents an array of non-French case studies that predate and succeed May ’68, where the right to participation and self-governance were mobilized to subvert conventional curricula and administrative structures. ‘Post-Independence Modernization’ showcases experiments of national self-determination through architectural education in settings like Kumasi and Baghdad, where resistance to power structures extended beyond the mandates of local institutions. ‘Postwar Modernization Labs in the East’ presents two seemingly antithetical educational laboratories in Japan that both turned to the sciences and ethnography in order to provide new modes of architectural pedagogy. ‘Experimental Media Politics’ demonstrates how architectural politics are not merely performed through drawings, models or buildings, but also through the form, content and dispositions of media that are mobilized as teaching tools. ‘Politics of the Body’ regards non-orthodox educational settings where questions of physical and symbolical access to architecture – and by extension to the cultural ‘edifices’ and processes it houses – served as points of departure for challenging traditional design priorities. Lastly, ‘Feminist Pedagogies’ introduces key examples where female activists in North America fiercely campaigned for women’s fundamental right to design education through self-organization and hands-on action.

Different sets of cases could have been selected and even the cases selected here could be placed in other threads. More than anything, it is the weaving of all the different threads and the equal value of all the different cases in all the different locations that is the key quality of the archive and of the period. A small set of hierarchical educational models incubated in Western Europe were undermined by a trans-national horizontal network linking multiple educational strategies with multiple understandings of the teacher-student relationship and the education-society relationship. All these threads were continuously cross-pollinating each other through publications, video, and the constant international mobility of the protagonists.

Radical Pedagogies is a project of collective intelligence. In that respect it is a scholarly and pedagogical experiment in its own right that questions traditional models of academic authorial production. It delves into the largely uncharted territory of extra-large collaborative projects that source expertise from a global network of scholars – a model with a large history in the academic fields of the sciences but rarely the humanities. Radical Pedagogies seeks to present a horizontal cut through architectural education throughout the second half of the twentieth century – a history of which, or multiple histories, has yet to be written.

References

- For full credits and current contributions, consult the online platform of the research project, www.radical-pedagogies.com.

- The exhibition ‘Radical Pedagogies: Action-Reaction-Interaction’, presented at the 2014 Venice Biennale, was curated by Beatriz Colomina, Britt Eversole, Ignacio González Galán, Evangelos Kotsioris, Anna-Maria Meister and Federica Vannucchi. The next public presentation of the project will be at the 7th Warsaw Under Construction Festival organized by the Museum of Modern Art in October 2015.

- R.P. contribution by Jean-Louis Violeau.

- R.P. contribution by Anna-Maria Meister.

- For the institutional history of the HfG see René Spitz, Hfg Ulm: The View Behind the Foreground: The Political History of the Ulm School of Design, 1953-1968 (Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges, 2002).

- Contribution by José Esparza; on the introduction of the new curriculum, see: Arquitectura Autogobierno: Revista mensual de material didáctico n.1 (October 1976).

- R.P. contribution by Ignacio González Galán.

- R.P. contribution by Masha Penteleyeva; also, Giancarlo de Carlo, “Preface,” The Ideal Communist City (New York: George Brasilier, 1971).

- R.P. contribution by Andrea Merrett

- R.P. contribution by Kathleen James-Chakraborty; as well as Raymond Lifchez and Barbara Winslow, Design for Independent Living: The Environment and Physically Disabled People (London: The Architectural Press,1979).

This article was published as a part of the ‘Radical Pedagogies: Reconstructing Architectural Education’ insert in Volume #45: ‘Learning’.