Alchemy of the Classroom

To be an Architect

The 2013 film The Competition follows an employee from Jean Nouvel office, a ‘head of projects’, navigating his level on the pyramidal scheme of organizing conventional contemporary architecture offices. (1) The image of this man, suffering the pressure of the genius-boss, trying to respond to deadlines with the effort of sufficiently trained and motivated young architects working behind him, neatly draws one of the professional glass ceilings that most accredited architects can expect in their working life.

This inherent scheme of suffering-when-practicing goes back to academic education, where students are subjected to endless working hours to learn the skills to do little more than efficiently configure space. With regards to architectural practice and education, the first reaction is to think this is ‘business as usual,’ but why does it work this way? When we each decided to study architecture we were moved by more or less by similar reasons, namely: to do something creative, to work on a different range of projects with different skills, to have a multi-disciplinary background and financial stability. The image of striking projects and a list of outstanding mentors would guide us through the exhausting path to become an architect. Inspiration was triggered by university leaflets that used words like: ‘exciting’, ‘inspiring’, ‘provocative’, ‘boundary-pushing’, ‘high-achieving’ and some ‘environmental’ additions to be ecologically sensitive.

The image of Howard Roark, the individualist genius in Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead (2), is still unconsciously promoted in most architecture schools. This ‘praise of the Self’ floods into our interior lives and pushes us through endless nights of designing and drawing in a surprisingly never-ending race.

In praise of Excellence

What are the motivations to choose any specific school? With some variations you may find surveys and reports that highlight factors like teaching quality, employment rate, student satisfaction, cost, location, academic reputation, program, and faculty/student ratio. Following contemporary trends, entrepreneurial rankings have become something valuable (3), however the single and most important motivator is the university’s reputation, especially when looking through the eyes of potential employers. (4)

A closer examination of such methodologies reveals that rankings give a measure of excellence, but also of endogamic self-reference. They are full of charts and fact and figures (5), but it’s difficult to find a single trace or connection with the actual education of the future professional and the context where they are intended to develop his or her practice. It seems that academics are more concerned about having an impact in indexed journals than having any impact in society. It’s possible to argue that this is precisely the way to ensure high quality education for future professionals; but maybe that’s the point to be questioned. Do we have the academia we deserve? If our answer is based in terms of commodities or exchange, then it could be yes. But it is rather evident that there is still a gap or disconnect between academia and society, which at the end is our field of work.

Not without irony, this search for the best architectural education occurs in a world where most of its built realizations are still vernacular. (6) We could argue that those ‘best’ schools are preparing leaders to build up the future urban environment, but several inconsistencies like real estate bubbles, precarious labor conditions and inequality insist on presenting us with a different reality and questions the convenience to prepare professionals for such a disconnect.

Now, our society is undergoing profound shifts and changes – we have seen it in industries as diverse as music, publishing and transportation. Yet universities and academia continue to operate according to entrenched archaic models. Economic growth throughout the 20th century transformed academia itself into a commodity system, in which not only education but also our social and cultural reality responds to the same political and economic logic. Following Bernard Rudofsky, we can see that “part of our troubles results from the tendency to ascribe to architects – or, for that matter, all specialists – exceptional insight into the problem of living, when in truth, most of them are concerned with problems of business and prestige.” (7) Is it time to quit drinking from the fountainhead of excellence?

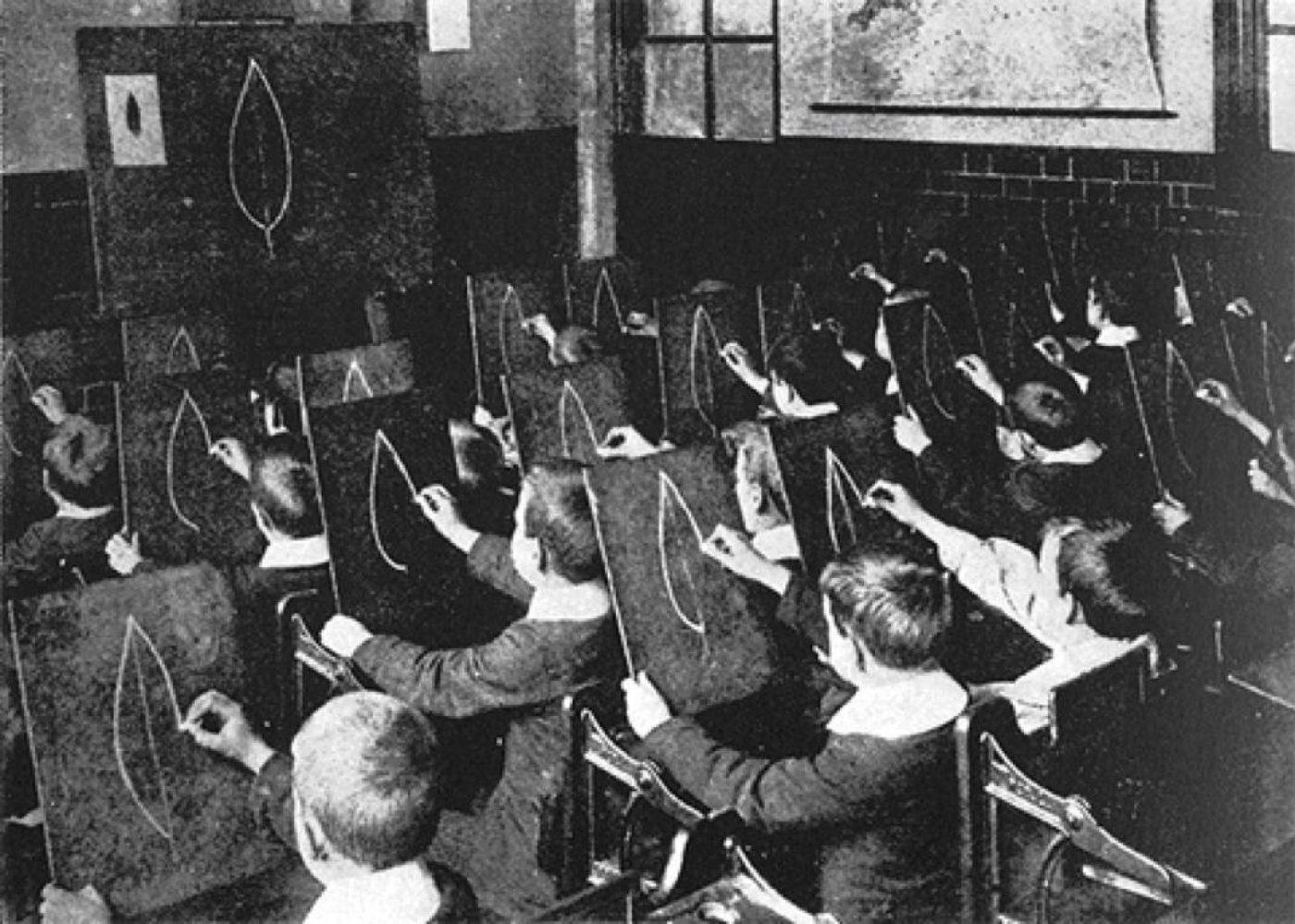

Burning the desks

Arthur Rimbaud always defended the need of creating new languages – an alchemy of the word – to understand and decode the world. (8) Perhaps this is something to learn in architecture faculties, where the lexicon is still dominated by the same words of the past century – innovation, accreditation, excellence – the same words that are often used by business and marketing schools; a kind of language that might not be useful anymore to break down the quality/quantity dilemma in the architectural field.

Jane Jacobs argued that ‘accreditation’ is an indirect legacy of the United State’s Great Depression matched with growing post-war economies. High unemployment levels and the repeated rejection and its burden of shame and failure strengthened the idea of having a job as the most culturally valuable product. From the 1950s, when stagnation lifted, the main cultural goal became assurance of full employment through development and a growing economy. Understanding that economic development in any field was dependent on a population’s knowledge background, academic administrators reasoned “the more of this crucial resource their institutions could provide and certify, the better for all concerned.” (9) This belief was definitely supported by the cultural ideal of nuclear families to support their descendants to get better jobs and better life conditions than their parents.

“All universities possess their own subcultures, and so do departments within universities, varying to the point of being indifferent or even antagonistic to one another, so a generalization cannot describe all accurately. But it is safe to say that credentialing as primary business of institutions of higher learning had gotten under way in the 1960s. Students were the first to noticed the change.” (10)

This somehow explains the pedagogical burst of initiatives and radical reactions in the second half of the twentieth century questioning academia, as part of a critical position to the whole system. (11) These alternative pedagogical experiences seemed like healthy reactions that could somehow invigorate and renovate to the system of academic education.

According to Giancarlo De Carlo, the university protests that exploded in the late 1960s were the most important event since the end of the second World War. (12) De Carlo was especially talking about faculties of architecture, which, in his own words, “had long been dominated by an academic body interested only in preventing new ideas from penetrating into the school.” How to subvert that situation? During those years, architecture students were questioning not only the hierarchical and endogamic structures inside the faculties, but more deeply the reasons for being an architect. It’s not an easy question, after all.

The Ignorant Architect

The architect has usually been related with those in power, as we have learnt that building is an expensive practice; something commonly highlighted in syllabi and programs to attract more students. Now check out the program of the architecture institution where you studied, are enrolled or affiliated with. Their means, purposes and methods are basically and still based in tectonics, history and general physics. But beyond the traditional programs, what about new fields of intervention that somehow relate architecture with places, relations between people and the challenges of our times to come such as urban data driven design, social physics, urban politics, curatorial practices, artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, literature and other fields of action that describe the complexity of the environments we inhabit? Moreover, the number of practitioners that are already exploring such fields or disciplines is significant in this regard.

Means of exploration are often driven by a mix of curiosity but also by the necessity to discover new ways of living. This sort of forced emancipation recalls the intellectual experience that Jacques Rancière writes about in The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (1991). The book describes the pedagogical experience of Joseph Jacotot, a French teacher who created a method of “intellectual emancipation” that demystified the authority of the teacher as one who imparts to the students what he knows and what they still don’t know. (13) In this way, knowledge is received, absorbed passively and then simply reproduced. On the contrary, Jacotot’s method resembles the process of learning language where experimentation, exploration and imitation are more effective than conventional teaching. By reducing the alleged superiority between the master and the student, Jacotot inverted the logic of a system based on explanations. Arguing that intelligence is shared and manifested in all products of human labor (everything is in everything), Jacotot pointed to the possibility of an incremental acquisition of knowledge by self-instruction. Jacotot believed that conventional explication stultifies learning by short-circuiting the journey that the student is able to make, thus creating an unconscious “veil of ignorance” and a duality game of superior and inferior intelligence, between the master and the student.

At the starting point of Jacotot’s method is a distinction between two human traits: intelligence and will. Students may just need to follow the teacher’s will, who guides them towards the subject. In Jacotot’s classes, the students learned using their own methods, not his. As a primary example, Rancière explains the case of Flemish-speaking students who learned French using the bilingual version of The adventures of Telemachus by Fenélon as the only tool, which allowed each student to see, recognize and compare both languages. The particularity was that the master didn’t know a word of Flemish, and his authority relied only on the fact that he was a native French speaker. The method of intellectual emancipation worked by being guided only by will and sharing among equals.

“Teaching cannot tolerate silence. Jacotot’s teaching method (which he described as ‘emancipatory’) is more like friendship, and friendship does not reduce the distance between people, it brings that distance to life. Perhaps this is the primary responsibility of the teacher, not the reduction but the vivification of distance.” (14)

Even though this story happened in the early nineteenth century, Jacotot’s experience brings to mind some of the turmoils we are currently facing two centuries later. The ‘order of things’ promoted by those in power leads society to accept what is taken for granted as such and reject intellectual revolutions for the simple reason that these attempt to undermine comfortable positions. Reality is passing by in front of an academia that needs transversality, openness, and joy in education, but it’s difficult to do so until we realize that it’s time for academia to unlock its doors to start learning from the emancipated ignorants outside. That would mean a real shift in the means and procedures to grant Open Access to the production and exchange of knowledge; disassembling bureaucratic structures and elite positions that consume and demand new resources; and start using public and private funds to secure the provision of knowledge nodes reachable by anyone willing to learn and teach, disregarding their provenance and income. Is that public education? No, it’s public emancipation!

It seems that the aforementioned experiments in radical pedagogies that emerged during the late 1960s and continued into the 1970s, such as those by the hand of Buckminster Fuller, John Hejduk, Giancarlo De Carlo, Superstudio, and others, were influential, but quickly became diluted and remained as ‘experiments’ – which are still the focus of PhD research and studies – instead of provoking real structural shifts inside architectural faculties. Shouldn’t we ask ourselves, why? For as long as the fascination for characters like Jacotot or other radical pedagogues and their ways of teaching and learning remains as a nostalgic reference for the ‘good old past’, it will be difficult to discover how to move forward. One of the reasons to understand why the traditional economic and bureaucratic system in academia hasn’t changed is possibly because not only education but also our social and cultural reality have become ‘schooled’, as Ivan Illich points out in his book Deschooling Society. Illich states that universal education through schooling is not feasible, and adds that “the current search for new educational funnels must be reversed into the search for their institutional inverse: educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring.” (15)

For Jacotot in the early 1800s the most powerful tool for emancipation was the book. Nowadays we have more tools than ever, and emancipation should come from the use we make of them; the way we exchange knowledge currently includes open access to information, new technologies, site-specific practices, and numerous non-site-specific ones like on-line courses and twitter chats, among many others that don’t necessarily go through the academia. Nevertheless, it’s very difficult to demystify years of the same inputs, and some of the practitioners working on the margins of architecture should be wary of becoming an updated heroic version of Howard Roark, perpetuating the master and the student roles. We should distrust those who bring headlines referring to the ‘death of the architect’ or the ‘death of architecture’, while at the same time showing the paths for change.

As soon as prospective students realize that they are being prepared for a world that doesn’t require all the skills they are paying tuition for, they will become aware that they are already learning and teaching the contents that really interest and provoke them – those that will configure their future practice (whatever its name) – by sharing through relational networks. By this understanding, emancipated students and teachers would be less prone to accept the scenarios of debt, fear and inequality in labor that are constantly reproduced in capitalist work-life.

How to catalyze change when relying in the same old vocabulary? Perhaps the first clever movement would be to ‘unlearn’ unconscious concepts, ideas and references that have been acquired during the academic years, from debt and fear to excellence and prestige. We should critically decolonize our minds and start questioning the importance of an accredited academic curriculum, the hierarchies, the economic system behind them, and the ego of the Self in architecture.

Paired with this, we foresee an alchemy of the classroom, transforming it into a node of exchange, where you can go (connect, attend) to share and learn; not to ‘teach’ in the conventional sense of a master giving pieces of knowledge to minds that live in ignorance, but to use Rimbaud’s alchemy of the word, to reframe the [academic] world. Previous knowledge based on the experience of architectonic realizations like calculus, chemistry, soil science and physics should then merge with new fields of exploration that describes the layers of reality within which we are now immersed. That is the material we already have and that can be shared in spaces of exchange, transformed by a new understanding of the territories we inhabit and the means we use to occupy and modify it.

References

- Ángel Borrego Cubero, Office for Strategic Spaces (OSS), ‘The Competition’. Film, (2013).

- Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead (New York, NY: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1943). The title of the book which is an homage to the profession of architecture comes from the Rand’s quote: “A man’s ego is the fountainhead of human progress.”

- Corinne Jurney, Liyan Chen, ‘Startup Schools: America’s Most Entrepreneurial Colleges and Universities 2015’, Forbes, July 29, 2015. At: http://www.forbes.com/sites/liyanchen/2015/07/29/americas-most-entrepreneurial-research-universities-2015/ (accessed August 06, 2015).

- According to the QS World University Rankings the top universities are chosen by the following criteria: Academic Reputation, Employer Reputation, and Research Citations per Paper. QS World University Rankings, ‘QS World University Rankings by Subject 2015 – Architecture and Built Environment’. http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/university-subject-rankings/2015/architecture (accessed August 06, 2015).

- The Magnetic Fields. ‘The Book of Love’. 69 Love Songs, CD, (Merge Records, 1999).

- Figures move from 10% to more conservative 5%. According to the Centre for Vernacular architecture settled by the folklorist Paul Oliver around the 90% of world’s architecture is vernacular. http://www.vernaculararchitecture.com/ (accessed August 06, 2015).

- Bernard Rudofsky. Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1964).

- Arther Rimbaud, Alchemy of the World (Alchimie du verbe), (1873). At: http://www.mag4.net/Rimbaud/poesies/Alchemy.html (accessed August 06, 2015).

- Jane Jacobs, ‘Credentialing versus Educating’. In: Jane Jacobs. Dark Age Ahead (New York NY: Vintage Books, 2005), pp. 61.

- Ibid., pp. 47.

- For references in postwar experiments in architectural pedagogy can be found in the project: Radical Pedagogies by Princeton University. At: http://radical-pedagogies.com/ (accessed August 11, 2015).

- Giancarlo De Carlo, ‘Architecture’s Public’. In: Peter Blundell Jones, Doina Petrescu and Jeremy Till (eds.), Architecture and Participation (Abingdon: Spon Press, 2007).

- Jacques Rancière,The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (Stanford University Press, 1991).

- Gary Peters, ‘Ignorant Teachers, Ignorant Students: Jacotot and Ranciere in the Art School’. At: https://www.academia.edu/206845/Ignorant_Teachers_Ignorant_Students_Jacotot_and_Ranciere_in_the_Art_School (accessed August 06, 2015).

- Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1971).

This article was published in Volume #45, ‘Learning’.

This article was published in Volume #45, ‘Learning’.