Markus Miessen interviewed by Arjen Oosterman and Brendan Cormier.

‘Ivory towers’ and ‘paper architecture’ are common put-downs used to question the agency of critical and speculative thought. After the theoretical hangover of a Deleuze et al architectural education, many young critical thinkers turned to practice as a means to put their thoughts into action. We sat down with Markus Miessen, who has spent the past several years researching critical and spatial practice, to see what this means for the field of criticism.

Arjen Oosterman: We started this issue of Volume with a hunch that the role of criticism in architecture has changed.

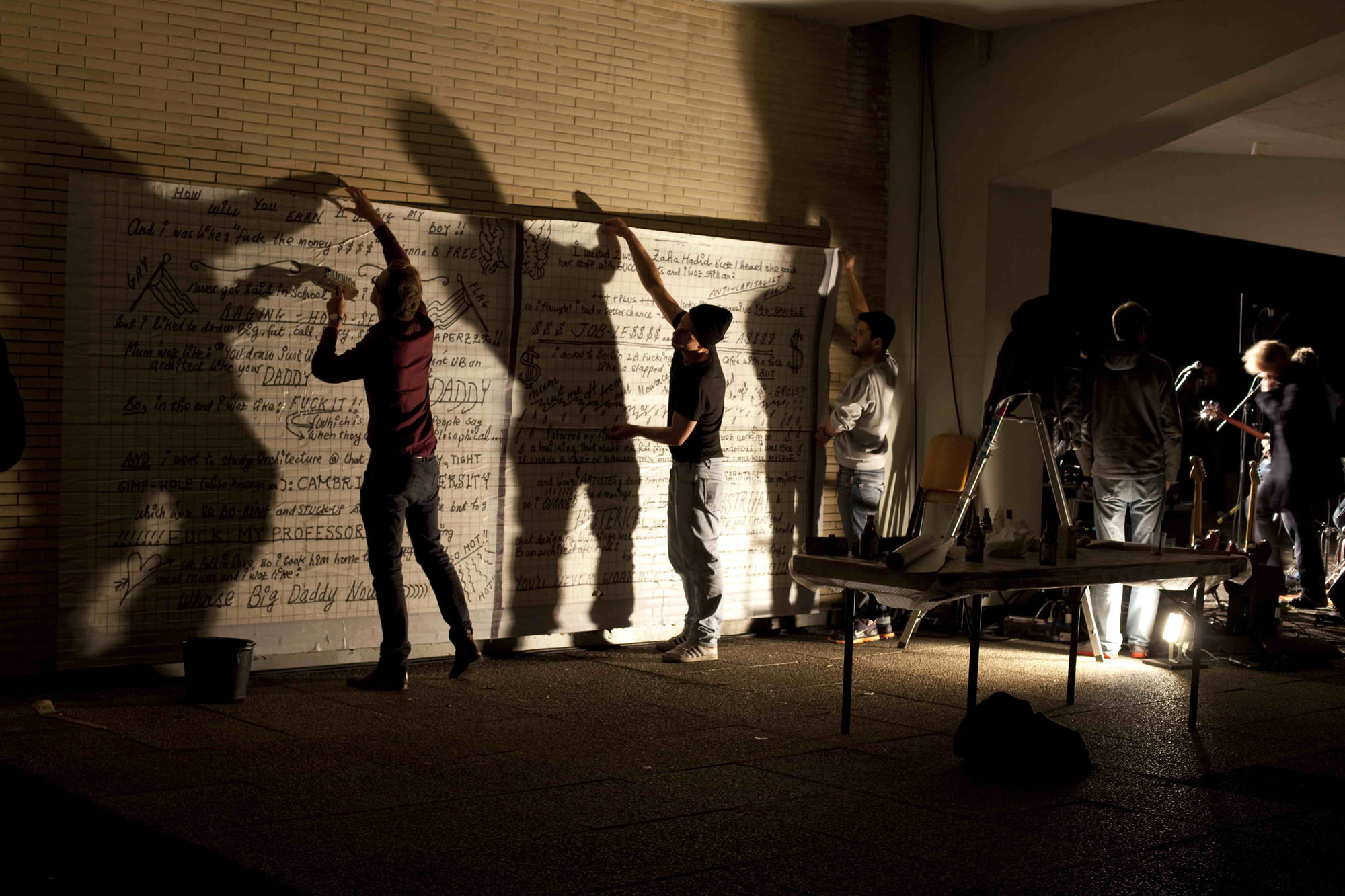

Markus Miessen: I agree. The question then is: how has it changed? When I look among my generation a lot of the criticism seems to have changed from verbal or written criticism, to the attempt to actually practice that criticism. Of course I’m not saying that theory isn’t practice; it is. Instead, I’m referring to an approach where issues that one is criticizing are addressed through a spatial practice. Now, maybe more than before, you see the attempt to deal with criticism through direct, spatial projects – like exhibitions and installations, especially at an institutional level.

Brendan Cormier: I notice you’re avoiding the term ‘critical practice’. You wouldn’t call this critical practice?

MM: I’m directing a program at the Städelschule in Frankfurt called Critical Spatial Practice (www.criticalspatialpractice.org), and I have to be careful about what I call critical. Part of the problem is that it’s very easy to claim or say that something is critical, but then at the end of the day, what exactly does it mean? On a purely theoretical or argumentative level you can make certain claims, but then one has to transfer that into something that actually holds ground with claims that can be substantiated. That’s the role of what people call critical practice, or just practice with a conscience. In terms of the reality of practice, the biggest difference is the moment you want to ‘practice critically’, usually you are unfortunately also exposed to a different kind of economy. Which means the moment you want to ask questions, or the moment that you interrogate certain existing protocols, or the moment that you don’t necessarily go with the default models of how things are done, you’re jeopardizing your economic stability, which among my generation is already pretty precarious.

So the question is: how can you? If it’s a self-initiated endeavour you need some kind of external funding, or if you’re working with a client then this client must trust you enough to actually challenge some of his or her realities. On an institutional level this is interesting because you really can challenge certain things, but it depends on whether the director is willing to actually risk something. It was very interesting to work for SKOR in the Netherlands for two years, because I had the fantastic opportunity to really re-think, together with Fulya Erdemci and Andrea Phillips, what SKOR could be. Unfortunately the moment that this process was finished, the institution disappeared.

AO: It’s interesting that you mention this shift from verbal to practiced criticism, and the complications that come with that. Because in the seventies up to the nineties architecture as practice had outsourced criticism to this different species called critics, freeing its hands for production. That was a model that seemed to function for both parties. But that reality seems to have changed nowadays. Is that what you’re arguing?

MM: Yes, this is exactly my point. This kind of outsourced critic, I wonder today who this is. If we were to look at the traditional role of a critic – someone who comments or reflects on what, bluntly speaking, other people do – and if I leaf through a majority of architecture magazines, I wouldn’t know any more who these people are. I don’t think I could come up with ten names of traditional critics. I find that this is not only true for architecture or spatial practice, but it’s the same in literature, in cinema, even in the arts. It’s much more about rather mediocre summaries of what is happening rather than in-depth and informed critique. If you look at exhibition and book reviews, so often they’re nothing else but very factual summaries of what the book or the exhibition is about – no contextualizing within a larger reality of what’s going on.

AO: Does it have any consequences for how the professions operate?

MM: The only immediate consequence that I can think of is that basically now each large architecture office has at least one in-house professional press person, that writes all these fantastic press releases that are then copied-and-pasted. It’s the same for literature and other fields and it’s a really worrying tendency. At the same time, magazines are struggling economically and often don’t have the luxury to pay someone a thousand euros to spend a week thinking about a particular show. Quite often, the people who actually write or critique projects and exhibitions – so basically spatial realities – haven’t actually been there, and that is very strange. Spaces are difficult to consider without actually having experienced it live.

BC: I’m curious about criticism particularly as this kind of feedback mechanism, how it informs practice. You were mentioning how it’s moved from the written word to the ‘practiced word’, so to speak. The question is: do you think that practiced criticism has an advantage in dialoguing with practiced architecture?

MM: I think the feedback mechanism is crucial. When one uses critique as some kind of practice, what’s absolutely important is that there’s an exchange with other people about what has been implemented or realized. It’s learning from process, and I think whatever kind of critique there is as a project, I don’t think it can be realized through one intervention; it’s a kind of struggle with oneself. In order to practice that way, you also have to have an agenda that supersedes the individual project, and that agenda can then be tested in the long term. Since architecture or any kind of spatial project takes such a long time to prepare just to be realized, it can be compared to a PhD. If you think of a PhD as a critical piece of writing, then you can also think about a particular approach to practice as a kind of critical device. If you start a PhD with an abstract, that abstract will change five times in the first six months of that project. It doesn’t mean the beginning was totally wrong, but that it’s being developed and adapted according to the kind of findings, research, and feedback you’re mentioning.

AO: But now you’re describing a process where the feedback is actually feeding into a continuous production process. In general, I think criticism as we knew it was a feedback mechanism after the fact. The product had been produced and then was received; it was being contextualized, it was being understood in many ways. It was made intelligible but it was also made cultural by critique. The problem that Volume’s predecessor, Archis, faced is that we were always discussing something that design-wise and decision-wise happened five years prior. But there also was this notion that you couldn’t talk about something before it was visible and ‘visitable’. Today we face a very different situation, as you also mentioned, where offices are the producers of our understanding of what they produce, but they’re also producers of the story even before it’s created. They advertise that they have just won or placed in a competition, or they’ve been invited to participate in one. So the story is already written before it actually starts. And all that material creates our understanding of what architecture is about.

MM: Yes, this kind of myth-building or the creating of a story around production is problematic. But getting back to ‘criticism after the fact’, let’s say there’s an exhibition or an architectural project that is finished and is being critiqued in that kind of traditional model, it stays on the level of critical commentary. But what I’m wondering is whether this kind of one-off situation can be changed towards a learning-from scenario, where critique actually is a way to slowly through a process change realities rather than simply just comment on them.

AO: Do you see ways to?

MM: The only way to do this is if there’s a personal agenda that supersedes the individual project. There needs to be some kind of red thread of a particular interest that you can test through different projects and different contexts, and this turns into an ongoing learning process for yourself. Maybe this is also the question of critique. It doesn’t necessarily need to be a critique about something or someone else; we can understand critique as some auto-critical vehicle. Use your projects or practice to somehow try to get closer to the agenda that you’re interested in, which of course sounds very ego-driven, but that’s not how I mean it. It’s more about how you can use the way that you practice to develop and critique an agenda that you’re interested in, and also somehow showcase that things can be done in a different way.

AO: Can we make it perhaps personal, a bit autobiographical? I vividly recall the first contribution you delivered to Archis in 2004: ‘Wet Dreams and Architecture’. You were still an AA student, and you were quite annoyed. I would argue that right from the start, you faced this aspect of a critical attitude and how to translate this critical attitude into a practice.

MM: It came from personal frustration, which for me is usually the most productive and fertile basis for critique – when frustration becomes the driving force. The moment that you’re emotionally involved, it can trigger things that on a more pragmatic scale are simply not possible. The moment you’re affected by something, you’re also willing to give much more than you would usually. So in that case, it had a lot to do with architectural education, and the way I was experiencing it at the time.

BC: The question we’re also faced with is how to critique the critical practice. Over the past ten years there’s been this surge in practiced criticism, or critical practice, or alternative practices. We find that just by the fact that they’re operating outside of the normal architectural industry, we give them default approval. We don’t yet have the language for critiquing the critical practice, which I find very frustrating. Is that something you look at with your work at Städelschule’s Critical Spatial Practice program, to develop a language to critique critical practice?

MM: We’re definitely trying to develop a language. What you can see over the last fifteen years or so is this move towards the social, without really understanding why, or what it means. These so-called social or participatory practices were understood as this great different way to get engaged in urban culture or urban projects. And then all of a sudden the architect was being promoted as the new social worker. That for me is very tricky, because this happened without considering what this would really mean in terms of the role of the architect, and also the future of that role. Because if we look at it now, one decade later, you can actually see what happened: the architect is less and less relevant. Big architectural projects are usually not carried out by architects. Catchwords like participation and sustainability read really well in the title, but then the question is what does a title really change at the end of the day. The way in which self-initiated projects happen often has to do with funding, and in order to get funding, these kinds of catchwords are absolutely crucial. So for a while, at least in Germany, you could be pretty sure that if somewhere in your funding application the words participation or sustainability were there, you would definitely be on the winning side. This is still happening. I don’t know what to say, but this catchword trend worries me.

AO: I would like to ask a question about the role of the intellectual. There was an idea in the seventies, maybe a bit later, that the intellectual is needed to destabilize ‘the system’, to open up this margin for possibility. The system has an endless potential, whatever the system may be, to neutralize and absorb opposition or alternatives (repressive tolerance for instance). The role of the intellectual supposedly was to counteract this, to destabilize the system in order to keep it going, to keep it moving, to prevent it from stasis. That kind of understanding of what the intellectual could add to society has also changed. Or has it?

MM: First of all, I think the question is: what or who is an intellectual? One issue with even talking about the intellectual is that it gets misunderstood as elitist by the public. It would be helpful to try to use a different vocabulary that makes it less threatening. How can that outsider destabilize the existing notions, or protocols of practice, or the way that things are done? What I’m very interested in is to see how one can ask those kinds of questions through actual work: how can you use your work to pose different realities somehow? In that sense, the skateboarder is just as disruptive as an intellectual in proposing an alternative view on something. But the public has no expectation towards the skateboarder. There is this weird notion that there must be this kind of figure that is called the public intellectual. And you end up with figures like Peter Sloterdijk, who are of course fantastically witty and very exciting to listen to, but often the language used or questions debated, are so hermetic. It has a very particular audience, and not one that communicates to a larger crowd. Maybe it’s too much pressure on one person, this figure of the public intellectual. Maybe one should understand the intellectual as a kind of practice.

AO: But if you don’t focus on the person, but on the function of the intellectual, do you see at present this function being taken over by other mechanisms? Today we see a sort of loss of these old positions, and at the same time, you can argue that other positions have emerged; other mechanisms have come to the fore that maybe compensate or even improve on the situation.

MM: That’s a really good question, and it’s very difficult to answer because it’s totally speculative. I think partially it has to do with a loss of filtering devices. There are many voices now and that’s also a positive thing in terms of practice; it has become more horizontal. But at the same time, the reason why it’s less easy to understand or more nebulous is because there is no real authority. If you look at the web, for example, it’s a huge mess with a lot of super interesting things to look at, but it’s not really a digested form of information or knowledge. So the biggest question is how can we somehow reintroduce a kind of filtering device that will actually make it possible to speak, to talk to each other, on a level where we have similar information.

I’m not saying that there should be an authority, but I’m wondering what could be a mechanism to allow for a more productive conversation around similar issues. It could be an interesting project to really rethink what could be the platforms through which these critical practices could actually operate and collaborate. These people who are practicing in this alternative way, you would think it creates a large community of practitioners, but actually it creates camps. And there have been countless ambitions and projects with websites or exhibitions or publications to somehow unite this, but somehow it never really happened. This is what I find so funny, that if you look back, throughout the twentieth century there have been certain movements in architecture. If you look at the situation now, there’s no movement.

BC: There’s no Team 10.

MM: This question of a movement right now is totally crucial. Why isn’t this happening? Maybe we’re all working so individually that some of the bigger picture gets lost. So I think, even this issue of Volume could be a great filter in a way. To pause even – everyone is so hectic today. There are conferences about these issues, but everyone’s so stressed that they just come and present their usual stuff, and then everyone disappears. Maybe criticism could also be understood as a kind of pause: you don’t just continue the way you do, but you also give it a bit of time and space to really rethink what’s going on.