Toward a Collective Criticism

This article appeared in Volume #36.

The internet gets blamed for a lot of things, our current crisis of criticism being just one of its victims. The explosion of free content, the rise of unpaid bloggers, a diffuse democracy of likes and retweets, has surely weakened the authority of traditional critics. But in this new landscape Mimi Zeiger sees a host of new possibilities for architectural debate. Explaining her notion of ‘collective criticism’, she shows how platforms like Twitter can help build momentum on critical issues that often fall through the cracks of the pressroom floor.

“Video killed the radio star

In my mind and in my car

We can’t rewind we’ve gone to far”

– The Buggles, Video Killed the Radio Star (1980)

Be it books, buildings, or Betamax, it’s common to the point of banal that technological change evokes cultural crises. The ending and the transition into new modes and formats in transportation and communication have a history of unsettling the soul, not to mention the marketplace. In our current condition the graphs that chart accelerating change swing exponentially higher every time a budding entrepreneur signs a lease in Silicon Valley. Shockwaves tied to technology, however, no longer shake with singular force but vibrate with a million microcrises across culture. As such, the voguish angst over the demise of architectural criticism is less a crisis rocking the foundations of the discipline, but rather a technological microcrisis shaking loose long held assumptions and hierarchies within the practice. At issue is the shifting validity of different forms of media for the expression of criticism as technological changes and the revised formats born of these shifts give everyone the jitters.

This anxiety isn’t new, it’s a lagging stressor left over from the 2008 economic nosedive that impacted publishing in no small way. Still, there are camps that cling to the traditional outlets of newspapers and magazines, and even some who give primacy to print over digital versions of these mediums. Others champion the democratic ideals offered by blogs, bloggers, blogging – the everyman’s opine platform of choice. And many blame blogs for the death of criticism, the rise of PR-journalism, and for lousy writing in general.

But why continue to lament the current condition and pine for wittier, better-constructed prose, as has become popular? “Confronting endings has long been a central function of criticism: This task has been essential to art and architectural history since the modern fields began”, wrote Sylvia Lavin in an October issue of Artforum on pavilions.1 Let’s harness these microcrises, confront the condition of a distributed model for criticism rather than elegize. Since, as Lavin continues with a rhetorically flip, “In the complex ecology that characterizes our contemporary culture of excess, we can no longer assume that a population will die out simply because it has lost its connection to the most pressing issues of the day”. Applied to architectural criticism and not the global market of pavilion architecture, Lavin’s about face sums up the simultaneous renting of clothing over the lack of full-time architecture critics and the rise of books, conferences, and panel discussions, and, yes, essays, on the weathered subject of criticism. Indeed, on the website Future Exploration Network, futurist Ross Dawson predicts the extinction (the insignificances of present form) of the newspaper by year and country. The US and UK are first on the list with demises slated for 2017 and 2019, respectively, and the rest of the globe losing a daily a year over the next two decades.2

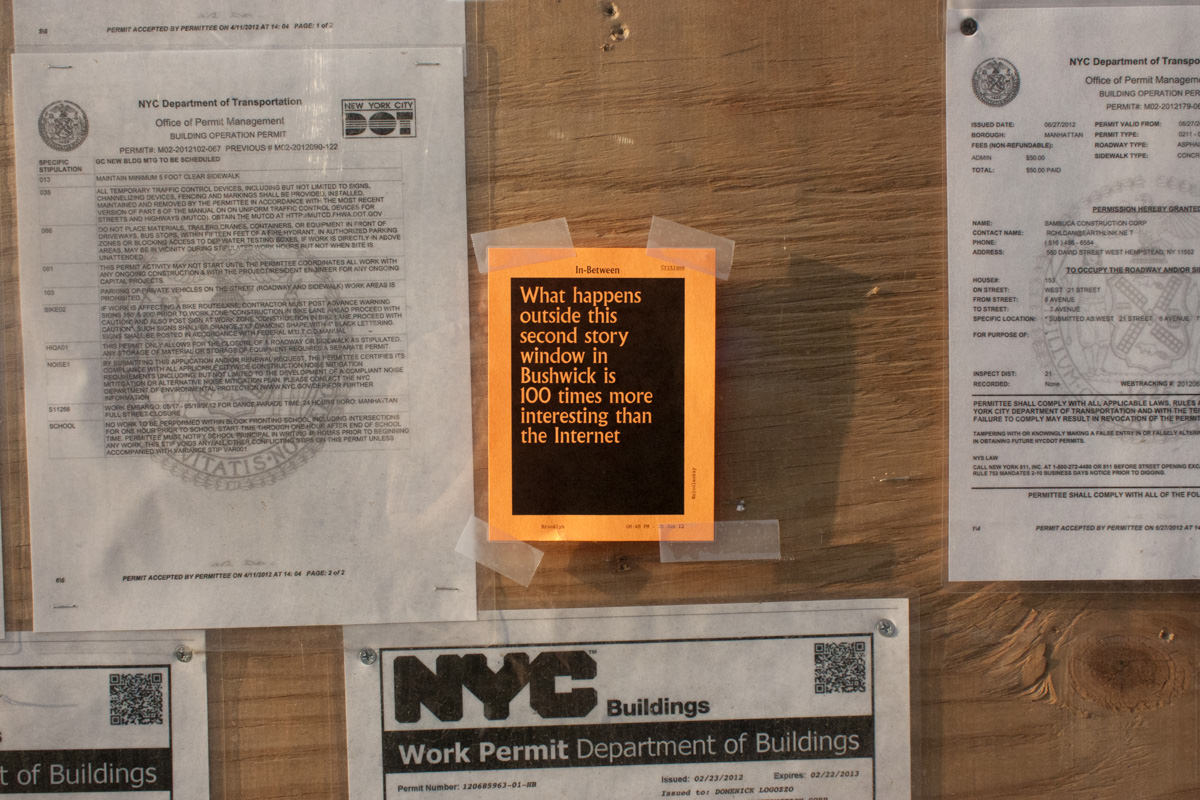

But if we leave graveside oratory behind, what we are seeing is not the death of criticism, but the devaluing of the authority of a singular critic. The platforms for criticism are rapidly expanding through digital and social media. What is the future of criticism in an era when critique can be reduced to 140 characters a tweet? The collective social web empowers the many and leverages the power of a networked public sphere. It posits a discourse built on commentary, where the authority that the newspaper critic once possessed is challenged by multiple voices. Old hierarchies that governed access and anointed the title of ‘critic’ remain intact, but easily circumvented by Twitter, Tumblr, Wiki-driven platforms, as well as image and GIF-based apps such as Instagram and Loopcam.

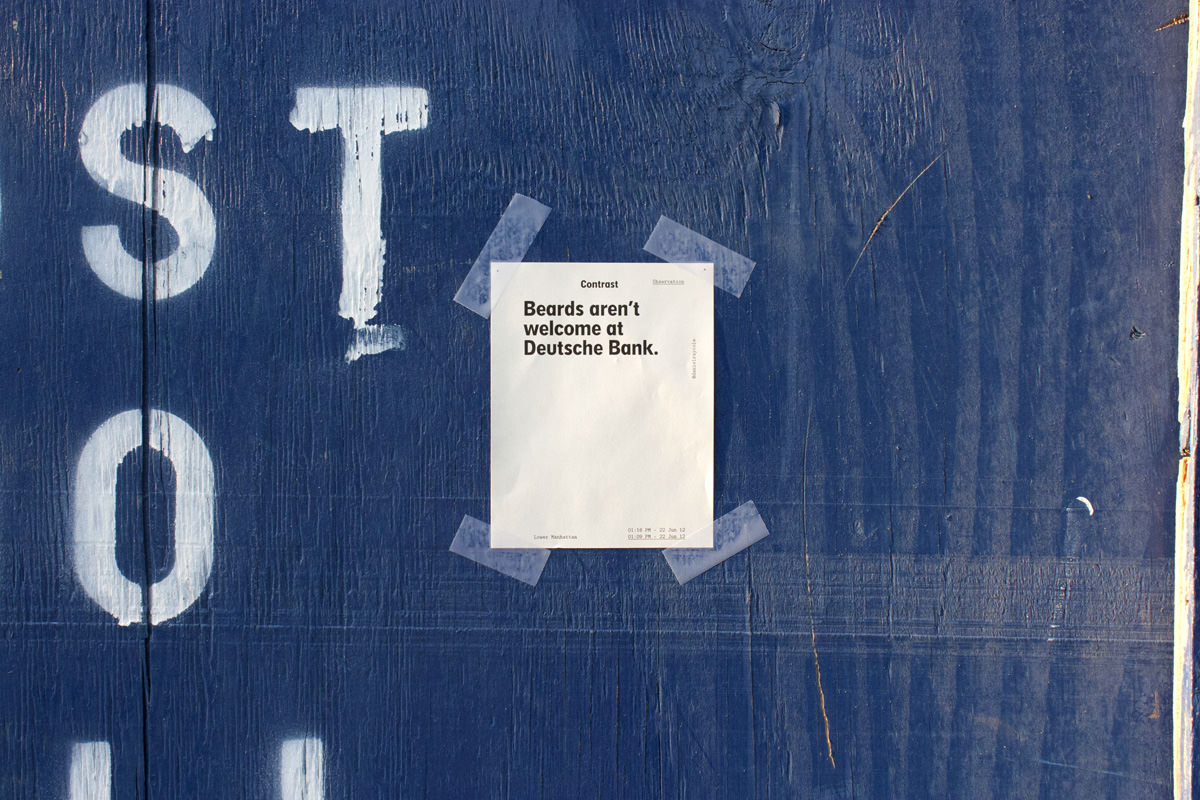

I suggest the term ‘collective criticism’ to describe this phenomenon. Collective criticism is born of the social web. It operates on, across, and between platforms. It is made up of individuals, but takes its power from responsive dialogue, not autonomous authorship. Simply snarking from the ether doesn’t count.

Collective criticism bears resemblance to crowd-sourced journalism, where distributed citizen journalists contribute to news stories via online tools and in doing so turn reporting into a model of aggregated production. Like crowdsourcing, it draws on both expert and amateur sources. But collective criticism isn’t after the neutral or seamless outcomes that categorize journalism. Instead, there is an emphasis on extended research, dialogic critique, and debate.

Take, for example, a dialogue that began on Twitter between Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne and writer/academic Javier Arbona. The story begins with the following tweet from Hawthorne at 2:13 p.m. on February 24, 2011:

“A coup for Michael Maltzan: $268-million performing arts center planned for SF State. http://lat.ms/fselv3”3

The url points not to a critical essay, but rather to a post on the newspaper’s Culture Monster blog which features several renderings of Maltzan’s proposed Mashouf Performing Arts Center along with Hawthorne’s singular endorsement. To which Arbona replied: “A what??!”, aghast that such resources could be found for signature architecture at a time when economic constraints across the state universities and colleges were slashing programs, including, as Arbona mentions, the San Francisco State University’s urban studies major.

What follows then is a series of tweets and additional news stories on the Maltzan proposal that unfolded on Twitter and included postings from @smallspace aka Lydia Lee from The Architect’s Newspaper, @JohnKingSFChron weighing in with a starry-eyed review of the renderings, a comment from Greg Walker on Archinect, and although it didn’t make it into Arbona’s final write up of the exchanges, I also contributed a few tweets that dug up the overall master plan for SF State.4

Meanwhile, Arbona continued to investigate the source of the financing, the background on funder Manny Mashouf, founder of the clothing line Bebe, and reports from the state auditor. The overwhelming abundance of chiming in, research, and dispersal back into social media at each stage of the critique interrogates the position of the L.A. Times architecture critic, and newspaper critics in general. Kazys Varnelis capped the nearly two-week dialogue with his blog entry from March 6, 2011. Entitled ‘Ivory Towers of Debt’, Varnelis writes, “…when design critics are unable to confront kind of issues that Javier raised in his piece, then we should be asking just what merit the field has in the first place, unless it’s merely cheerleading for the next building boom.”5

This accumulation of posts and tweets represents a collective criticism, with entries dependent on each other for meaning and impact. (Collective criticism should not be confused with collaborative writing, that’s supported by software such as Google docs or Medium.com.) Moreover, collective criticism rejects not only the primacy of the critic as architectural arbiter, but also the inherent privileges that come with access and exclusivity. Rubbing shoulders and chumminess with the key players within architecture dominates current discourse, obscuring the possibility for objective judgment. As such, with collective criticism, buildings are evaluated as cultural products within a greater context, not as formal sweets to savor or spit.

Collective criticism opens up the possibility of many criticisms, rather than a singular dominant discourse. It’s true that the overused truism ‘everyone’s a critic’ holds only minor sway when applied to the individual but it gains strength when understood collectively. In this way – with a nod to Bruno Taut and The Crystal Chain Letters and The Charlottesville Tapes – collective critics are both influencers and audience.

It’s here that Pierre Bourdieu might caution against this self-affirming, subcultural feedback loop, as he writes, “The almost perfect circularity and reversibility of the relations of cultural production and consumption resulting from the objectively closed nature of the field of restricted production enable the development of symbolic production to take on the form of an almost reflexive history.”6 Luckily, social media rescues us from endless navel gazing by allowing for the possibility of a more open field of production. In his book Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894, Alessandro Ludovico unpacks the importance of interconnectedness, writing “[T]he particular role of publishers within any cultural network (or even the entire network of human culture) is best fulfilled through free and open connection to other ‘nodes’ within that network. This is how we can generate meaning, and indeed bring some light, to the global network which we are now all a part of.”7

If there is a symbol that strives to bring meaning to this global network, it’s the hashtag (#). The pound or number sign (named octothorpe or octotherp by Bell Labs in the late 1960s) aggregates content together around a tagged theme. The multi-named symbol rose through history on a series of technological microcrises: a mapmaker’s shorthand, denoting agricultural fields; a printmaker’s invention to solve confusion around the abbreviation for pound; and at Bell Labs, engineers who needed a symbol to resolve the mechanical versus electronic input system. Today, the hashtag is digitally ubiquitous on Twitter and Instagram and the symbol holds the distinct power to convene a commons.

While #fail and #winning dominate the trend wars on Twitter, the platform still offers possibility for collective critical discourse. Recently, the cheeky and activist #FolkMoMA, served as rallying cry across the internet, bringing together writers and designers in protest of MoMA’s decision to demolish the American Folk Art Museum. The unnamed founders of the Tumblr FolkMoMA, used Twitter (@FolkMoMA) to foment activism. Their call for ideas asked for “draw/sketch/photoshop/collage possibilities of interaction for the American Folk Art Museum and MoMA buildings”8 and the projects were collected on Tumblr. Yet the crux of #FolkMoMA lies with the power of the hashtag, which led The Architect’s Newspaper editor Alan Brake to write the following on May 9:

“Sensing a renewed spirit of engagement & activism around equality, urbanism, architecture, & education. Exciting! #folkmoma #freecooper”9

But an earlier, perhaps more fundamental use of the hashtag, dates back to December 2009, where a conversation tagged #endofarchitecturetexts sparked a flood of tweets around the role of architectural criticism in the future of publishing in a digital age. #endofarchitecturetexts publicly included several participants: @sixsevenfive, @kushpatel, @TommyManuel, @solidk and @loudpaper (myself).10 The tweets in the conversation accumulate to form a critique, growing from commentary to dialogue to criticism of the very tools underpinning the discourse.

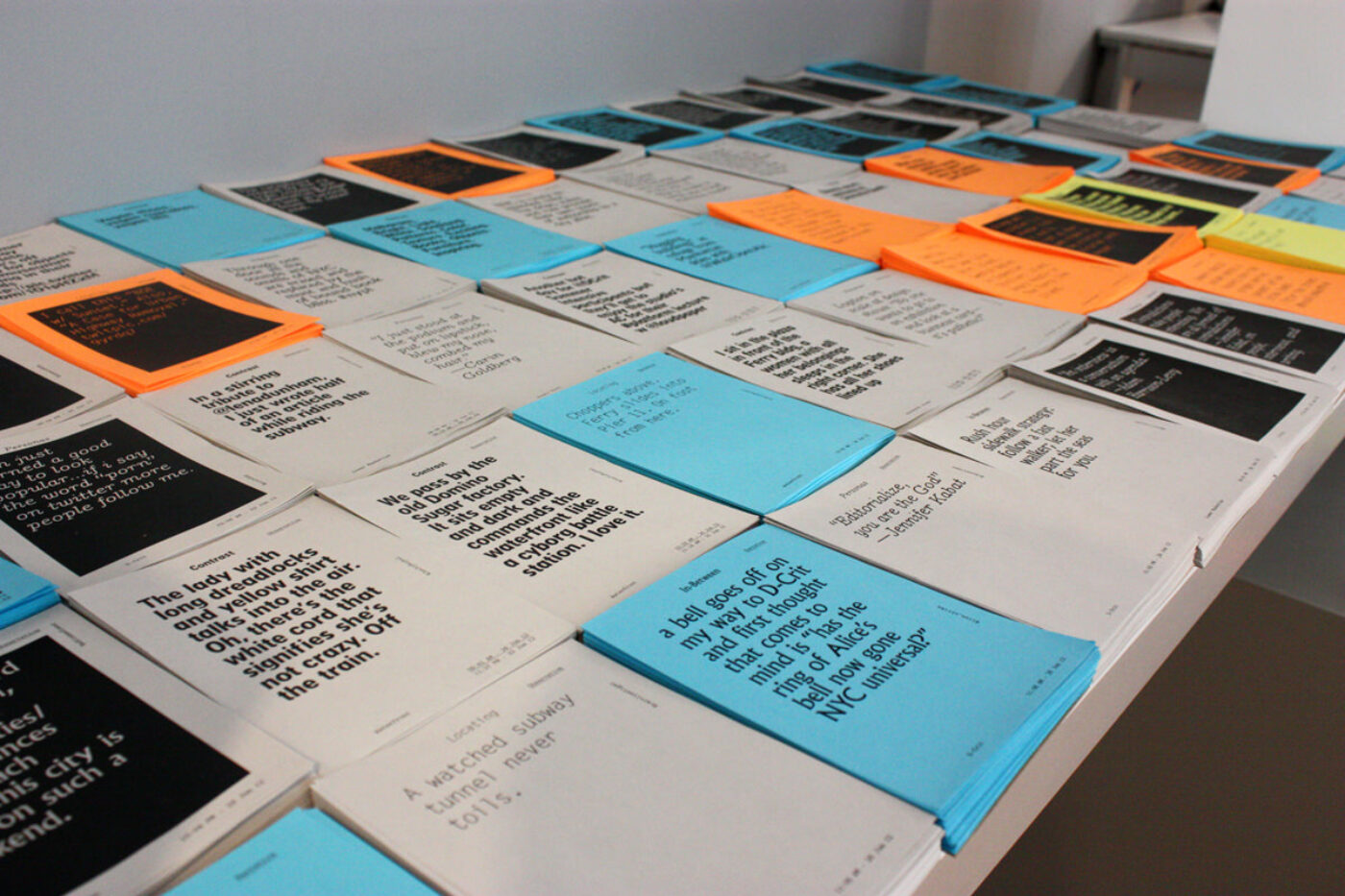

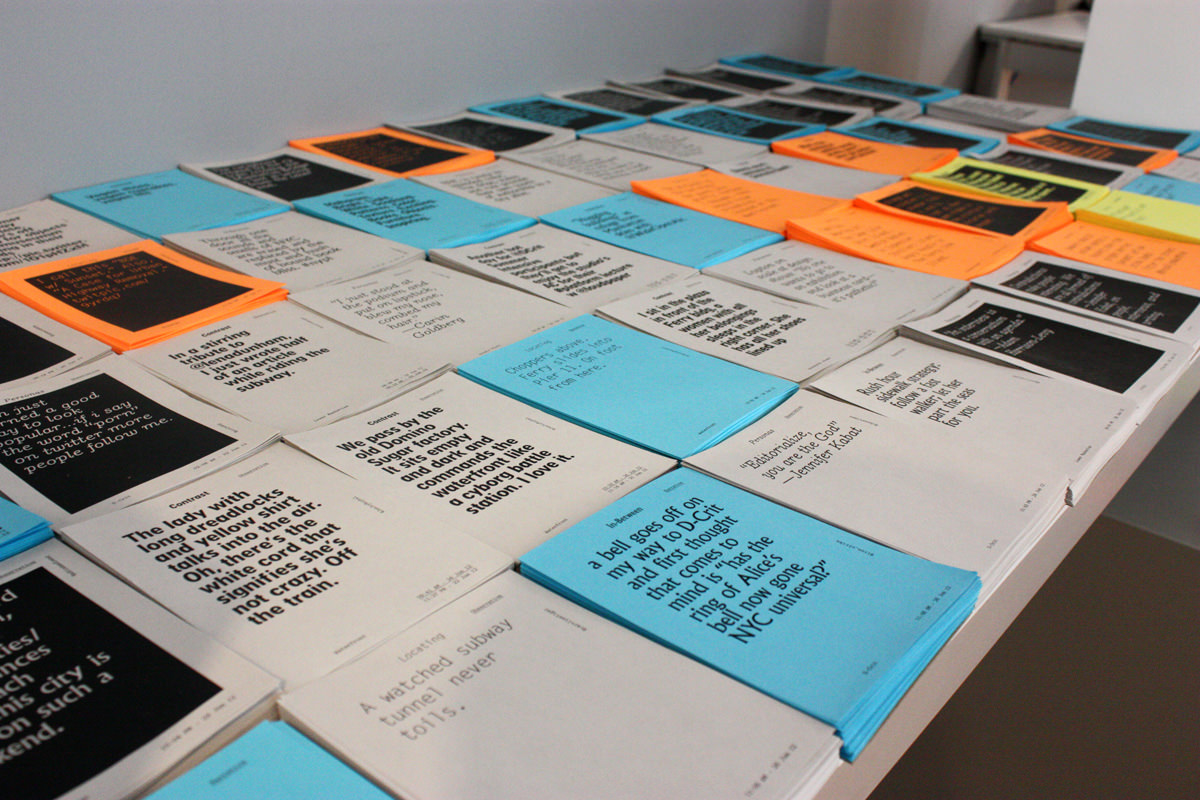

The extent of #endofarchitecturetext’s influence was captured by @solidk, writing as herself, Kamomi Solidum, in The Page + The Screen: An Annotated Bibliography for 21st Century Readers, a chapbook-like, post-course publication available in print and PDF developed by The Public School New York. She writes, “[The #endofarchitecturetext thread] was the impetus behind the proposals for the Public School New York classes, The Page + the Screen: Siting Text in the Early 21st Century and Beyond, and Texts + Textures: A Writing Workshop. It is also a formative document of the lgnlgn forum. It is important to note that at the tail end of the thread, the discussion turned toward how conversations like these, which are distributed across multiple platforms, will eventually be archived and interpreted.”11

Solidum’s question about how to archive and interpret collective criticism still remains unresolved. The very nature of the social web gives the impression of fleeting and ad-hoc chatter, even as our web footprints and data trails grow larger. As collective criticism bubbles up almost spontaneously from this pool of content, there is rarely a means to document or legitimize the validity of the critique. As such, collective criticism’s value, meaning, and import lies its ability to influence discourse, not from hierarchical status. We find collective criticism across platforms and at the nodes within the network, not on the masthead.

Notes

1. Mark Sylvia Lavin, ‘Vanishing Point’, in Artforum International, October 2012, p. 212.

2. Ross Dawson, Newspaper Extinction Timeline, 2011. At: http://futureexploration.net/Newspaper_Extinction_Timeline.pdf

3. https://twitter.com/AlJavieera/status/40852687067025408

4. Javier Arbona, ‘The Sorrows of Finance Capital’. At: http://storify.com/javierest/the-sorrows-of-finance-capital

5. Kazys Varnelis, ‘Ivory Towers of Debt’, March 6, 2011. At: http://varnelis.net/blog/ivory_towers_of_debt

6. Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production, Randal Johnson, ed., (Columbia University Press, 1993) p.118.

7. Alessandro Ludovico, Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894, Onomatopee 77, (Rotterdam: Onomatopee, 2012), p. 150.

8. http://folkmoma.tumblr.com/about

9. https://twitter.com/AlanGBrake/status/332647664682418177

10. http://lgnlgn.com/post/41426074448/may-2010

11. The Page + The Screen: An Annotated Bibliography for 21st Century Readers. (New York: The Public School New York, 2010). At: http://www.graphicunion.org/press/page-screen-annotated-bibliography.pdf