Euro Speak

The conflicting processes, which can both define or change borders and which classify who is ‘inside’ of Europe or who stays ‘outside’ of Europe can be labeled with the concepts of ‘inclusion’ and ‘exclusion’. The ongoing demarcation of ‘us’ and ‘them’ characterize debates on multiple levels, such as negotiations on EU enlargement and on definitions of citizenship, immigration and participation in decision-making. The terms ‘inclusion/exclusion’ are also common usage inside the European Union (EU); they were introduced recently by the so-called Eurocrats: The European Commission, for example, has used the term ‘inclusive society’ in several documents since the late 1990’s: in the Report on Education from the Portuguese Presidency (2001) and in the White Book on the Cognitive Society, September 2001. The White Paper on European Governance from July 2001 considers the ‘opening’ of the European Society as one of its most important goals.

The perception of a democratic deficit (to be regarded as one of, if not the typical and much cited symptom or phenomenon of exclusion from EU policy- and decision making) was first noted in the White Paperon European Governance.1 The document states that there is a ‘widening gulf between the European Union and the people it serves’ created by a perceived inability to act even when a clear case exists; when it does act it does not get credit for this and when things go wrong ‘Brussels is too easily blamed by Member States for difficult decisions that they themselves have agreed to or even requested’; that many people simply do not understand the mechanisms of the institutions; and all these factors lead to a lack of trust and disenchantment (pp.7-8). This analysis of the situation suggests that there are a number of democratic deficits including ones of knowledge, communication, and trust, as well as a ‘closeness’ deficit, and that they are a) not entirely of the EU’s own making and b) not always fair.

Research on media reporting across the European member states illustrates the relevance of the concepts ‘inclusion/participation/democratization’ on the one hand, and the emphasis on ‘exclusion/democracy deficit’, on the other hand.2 A large age and educational gap seems to persist in spite of some recent attempts to assist participation and democratization; young academics are in favor of the EU, whereas older and a larger proportion of female interviewees see themselves as ‘losers’ and excluded from important information.

Thus, the practices and politics of exclusion seem to be inherently and necessarily rooted in language and communication. This is particularly revealing, since the study of contemporary exclusion and inclusion cannot be straightforward for at least one basic reason: the ideological value of tolerance is widespread in contemporary capitalist societies, so that the explicit promulgation of exclusionary politics conflicts with the generally accepted values of liberalism3; this phenomenon relates to all EU member states. The very terms ‘discrimination’, ‘exclusion’ or ‘prejudice’, carry many negative con- notations. Few would admit to exclude, prejudge or to discriminate against minority groups or even against any European citizens. Yet, structured inequality continues to exist. For this reason, it is not only interesting but also necessary that the topic has tended to attract critical analysts, who do not accept what people say at face value, but seek to examine the ideological/discriminatory, often latent, nature of discourse.4

This means that it is essential to study how language and discursive practices can accomplish exclusion in its many facets without the explicitly acknowledged intention of actors; exclusion becomes ‘normality’ and acceptable, integrated into all dimensions of our societies. In some cases, exclusion occurs behind the backs of those who practice it, in other cases, exclusion is practiced explicitly, through language tests, citizenship laws, and so forth.

The German sociologist Niklas Luhmann defines inclusion and exclusion as the two most important ‘meta-distinctions’, because they possess enormous relevance to our societies: Certain social groups lead ‘parallel lives’. The social problems transcend the traditional values of justice and democracy. He states, that only the people who feel included still adhere to the democratic institutions of justice.

Therefore, I propose the following definition of (discursive and material) social processes of inclusion and exclusion: ‘Inclusion’ and ‘exclusion’ are to be understood as the fundamental construction of ‘in-groups’ and ‘out-groups’ in various public spaces, structurally and discursively, as basis for and with varying impact on conflicts, integration, negotiation, decision making and the genesis of racism and anti-Semitism. In the case of the EU, these in-groups and out-groups may differ for the EU member states (historically and politically) and for different public spaces, such as media reporting, laws, access to positions, to policies, schools, housing, language, citizenship etc., in sum to participation on and access to all levels of society.’

Strategies of Mainstreaming, Inclusion and Exclusion

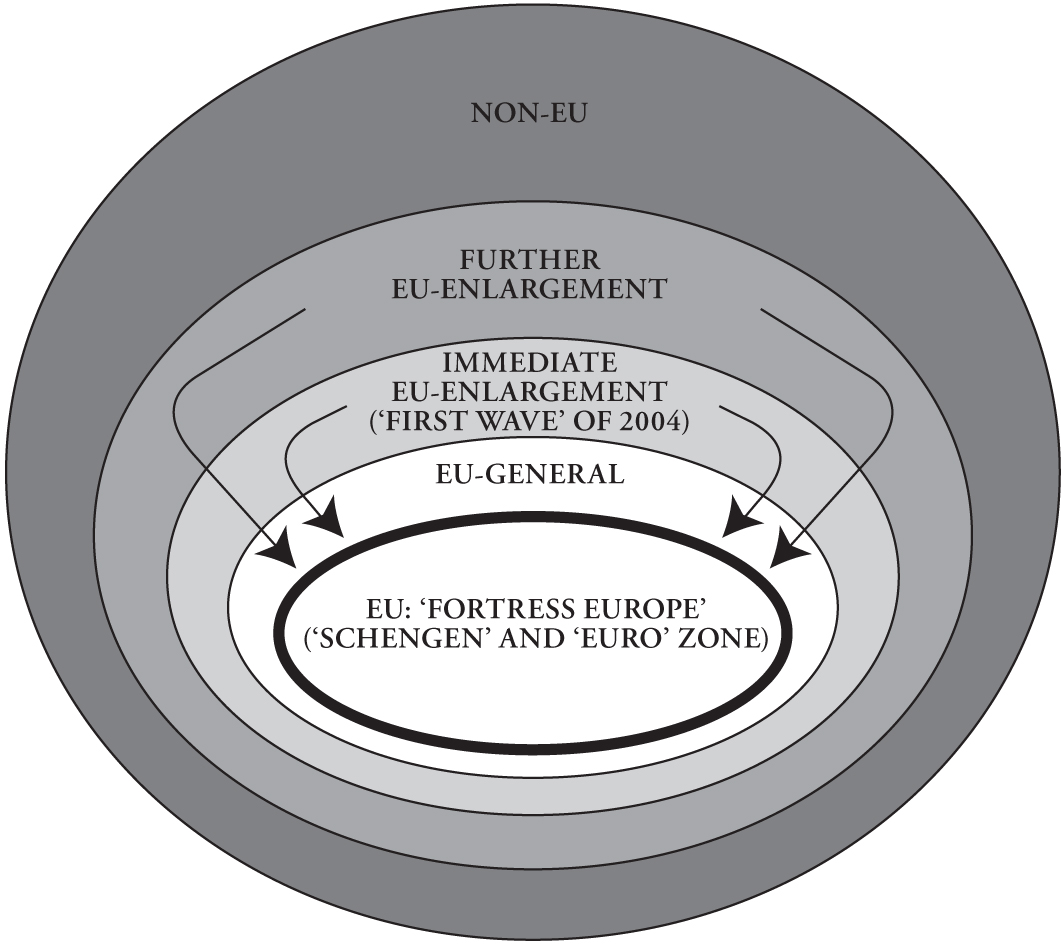

In their research on the construction of European borders, Busch and Krzyzanowski5 define Europe as consisting of concentric circles which show the ranges and also scale of being included or excluded, due to many legal treaties and agreements throughout the past 20 years:

Graph 1 presents, in a heuristic way, the more or less permeable borders constructed throughout Europe. Each ‘circle’ is based on a precisely defined set of laws; crossing these borders always entails permits, papers, visas, and so forth. Thus, the processes of construction and limitation of Europe gave rise to the reproduction of structural inequality/discrimination/exclusion between various social, cultural, religious, national and other groups living in Europe. Furthermore, the imagined constructions of ‘new borders’ within the European Union basically present an elite concept of the EU and its external borders, and not a concept endorsed or ‘imagined’ by most European citizens.

Recently, we did a few interviews with various members of the European Convention, a body which was responsible for drawing the reform plan of the EU and sketching out its future, conducted during intensive fieldwork at the Convention 2002⁄2003 in a project funded by the Austrian National Bank, on the ‘Construction of European Identities’. Within the European Convention representatives of governments and national parliaments of the ‘immediate’ and the ‘distant’ EU enlargement countries’ fully participated for the first time in drafting and constructing ‘the future of Europe’ with (almost) equal rights to all representatives from EU-member states and EU institutions. Of particular importance is the fact that the data has been gathered within interviews with members of the Convention from both current EU member states, as well as from the CEEC countries that were for the first time actively incorporated into EU bodies and institutions.6 As the research illustrates, the ‘outsiders’ have rapidly become part of the EU’s ‘inside’, involved in reproducing a vision of Europe as ‘the (core) EU’, a vision integrating clear borders of Europe. This implies that the members of the accession countries have accommodated and been rapidly socialized into Eurospeak and EU attitudes.

Another remarkable finding was that as long as others are clearly demarcated, the problem of integrating new members seems to be of minor priority. The fact that issues of migration and asylum policies were not discussed extensively in the Convention (unlike issues of autochthonous, national minorities) clearly implies that ‘foreign’ ‘others’ were not categorized as potential European citizens and excluded from the social construction of Europe.

To be included in the EU club, the CEEC countries need to ‘pass tests’ before being accepted. However, these tests’ are not sufficiently defined. Of course, in all accession negotiations, there are precise economic, social and human rights bench marks which need to be achieved. Nevertheless, the argumentative flow in our interviews suggest other standards which are at least presupposed, projected and part of the mental and emotional frames of the interviewees: To be accepted as ‘European’ entails – so it seems – a specific geographical location; the sharing of specific cultural and religious values and ideologies; and the agreement to define the ‘dangerous’ ‘others’ and to keep these outside Europe. Having once been able to join the club, others should thus be excluded or made to pass similar tests.

The Shift from Culture to Politics

The Danish historian and sociologist Jan Ifversen considers the move from a cultural definition to a sociological and political construction of a European identity to be one of the decisive conceptual changes of recent years.7 Ifversen traces the development over the last few centuries from a cultural meaning to one of civilization, and ultimately to a political construct. Accordingly, we find many contradictions and a variety of opinions about the meanings of Europe. Moreover, the dimension of inclusion and exclusion cuts across all the data analyzed in our study which are briefly summarized in this short essay. The general concept of insiders and outsiders is salient in all societies as well as between societies, in cyberspace, in every day conversations, and in organizational discourses.

Inclusion and exclusion are not to be considered static categories: the person who is excluded today may be included tomorrow, and vice versa. Although membership can always be redefined, important ‘gate-keepers’ decide who will have access: new laws, new ideologies, and new borders – in Europe and elsewhere. Mostly it is not up to individuals to define or redefine their membership: this depends on structural phenomena of exclusion. The desired ‘opening-up’ of the European Union, the greater participation and democratization, therefore still has to overcome some essential obstacles if it is to reunite the so-called ‘parallel lives’.

Telling. For his Homeless series Milovan Markovic interviewed homeless people in Berlin, Tokyo, and Belgrade. A short passage from the homeless’ life story is selected for the painting. Of the person portrayed it includes information about his personality, the conditions of his failure, and the influences of the surrounding culture and society.

Notes

- Commission of the European Communities, EuropeanGovernance, A White Paper, Brussels, 51-7-2001.

- F. Oberhuber, C. Bärenreuter, M. Krzyzanowski, H. Schönbauer, & R. Wodak,‘Debating the European Constitution: On representations of Europe/the EU in the press’. In: Journal of Language and Politics vol. 4 no. 2, 2005, pp. 227-273.

- M. Billig, ‘Discourse and Discrimination’. In: K. Brown (Ed.) Elsevier Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, Second Edition, Oxford (Elsevier) 2005.

- M. Reisigl & R. Wodak, Discourse and Discrimination, London (Routledge) 2001.

- B. Busch and M. Krzyzanowski, ’Outside/Inside the eu: Enlargement, migration policies and security issues’. To be published in: Anderson, James and Warwick Armstrong (Eds.), Europe’s Borders and Geopolitics: Expansion, Exclusion and Integration in the European Union, London (Routledge) 2006.

- Ibidem.

- J. Ifversen, ‘Europe and European Culture – a conceptual analysis’. In: European Societies, vol. 4 no. 1, 2002, 1-26: p. 3 ff.