Following Word War Two, London embarked on a highly prolific rebuilding campaign. But it wasn’t simply putting the pieces back together. The ambition of the welfare state combined with new ideas in architecture to produce radical new designs, altering the British landscape. The organization behind this was the London County Council, and in particular the Architects’ Department. Ruth Lang discusses the machinery of the bureaucratic system that enabled one of England’s most innovative periods in design.

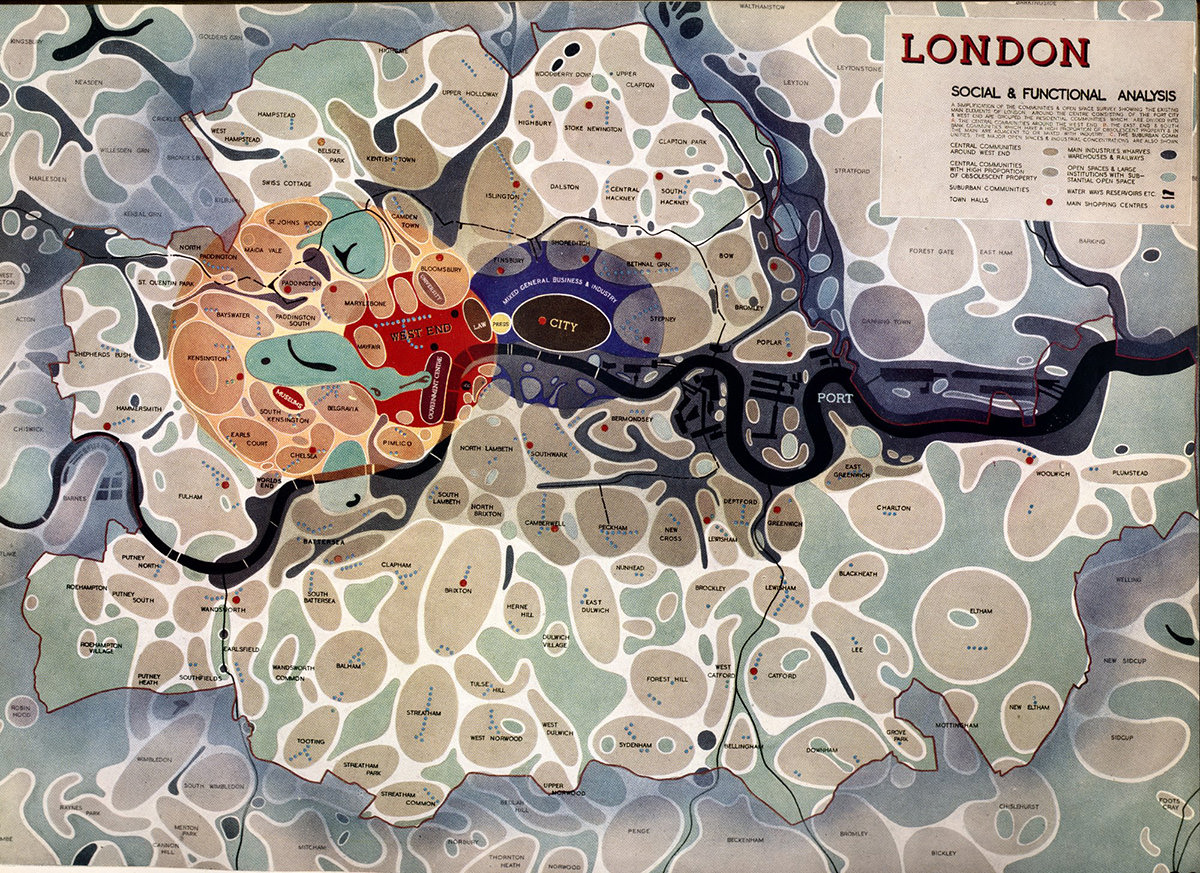

Even before the Blitz ravaged the cityscape in 1940, the British government were all too aware that London stood as a microcosm of the country’s urban malformations – an awkward grafting of industry and housing, still riddled with slums and throttled by a Gordian knot of transport infrastructure, its boundaries a hazy ‘pentimento’ of non-distinct metropolitan, sanitary, municipal and utility delineations which had been ceaselessly sub-divided and re-grafted back together over time. Their desire for rebuilding the capital after the war was founded not just on the human imperatives, but in setting an ambition for the nation to rebuild itself; fitter, healthier, more productive than before.

Following the end of the war, a zeitgeist of Socialist tendencies prevailed throughout the UK, which was partly a culmination of growing discontent with the pre-war housing, social and healthcare policies, and partly due to the feeling that having passed through such a fundamentally disruptive moment, society was unable and unwilling to simply go back to the way things were. The ‘common man’ – having been suppressed by those above in the social hierarchy, through their working conditions and their housing provision – had become revitalized by the realization that through uniting towards a common goal, they could be a powerful force for change. There seemed a feeling that they could turn this newfound strength to their own ends and create a better society for all, freed of the hindrances which had become engrained over time, and to start afresh on a new tack. It was out of this period and under the guidance of the London County Council Architects’ Department that the gleaming Portland stone clad people’s palace of the Royal Festival Hall at the heart of the South Bank, Goldfinger’s residential Balfron Tower, and the lumbering, ill-fated concrete spaceship that was Pimlico School were constructed – all icons of post-war construction in Britain, and still revered within the profession at least as examples demonstrative of a particular kind of Britishness and the socially-minded, technologically experimental and design-orientated architecture to which we still longingly aspire.

Yet the truly seminal structures being built at this time weren’t so visible, lying not in the material manifestation of architecture, but in the invisible systems created for their conception and delivery. For architecture, the real New Jerusalem of which William Blake once dreamt – and which Sam Jacob paraphrases in the title of this year’s British pavilion at the Venice Biennale – was built not of concrete, steel, and brick, but of the careful interweaving of immaterial factors, of constructing political structures, transposing professional relationships, and through forging links with education and industry. The buildings we revere were literally concrete manifestations of the public sector post-war values of open borders – professionally, culturally and tectonically – and of the working ethos of experimentation, industrial efficiency, and sociological research to which their genesis was intrinsically linked.

For the schemes they delivered during this period, with particular reference to Milton Keynes and Thamesmead, we extol the virtues of the pastoral and the picturesque as being part of the unique sense of Britishness. Reyner Banham, Paul Barker, Cedric Price, and Peter Hall ‘s contemporary Non-Plan1 is a key contribution to this, but it should be noted that non-plan does not equal unplanned, or without planning with a capitol P – the premise of such proposals were still fundamentally dependent on intertwined facets of research, organized high-level government initiatives (such as those for buying land and creating the supporting infrastructure) and in setting development parameters in order to determine the line between beneficial growth and harmful anarchy, both at the proposition stage and in their use.

The role of planning and planners in this period was not to create constraints to hold development back, but instead to act as a catalyst, providing a futurespective aspiration to rebuild the nation. While the architects’ department had been officially operating within the London County Council since 1889, their work was piecemeal, the main opportunities to create any visionary strategy for the city coming only as a result of fire, plague or war.2 Yet here was an impetus for change. The proposals they set out in the 1943 County of London Plan by JH Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie were wide-ranging and seemingly strident in scope, demanding the wholesale reconsideration not only of London as a self-sustaining County and also its role within the inter-urban structures of the UK. But this was also based on a sensitivity borne of research into sociology and the existing urban fabric, and a codependent understanding of the means by which these could be achieved through a working relationship forged between the Architects’ Department and the construction industry with an aim to develop a holistic strategy within which the nation could be rebuilt.

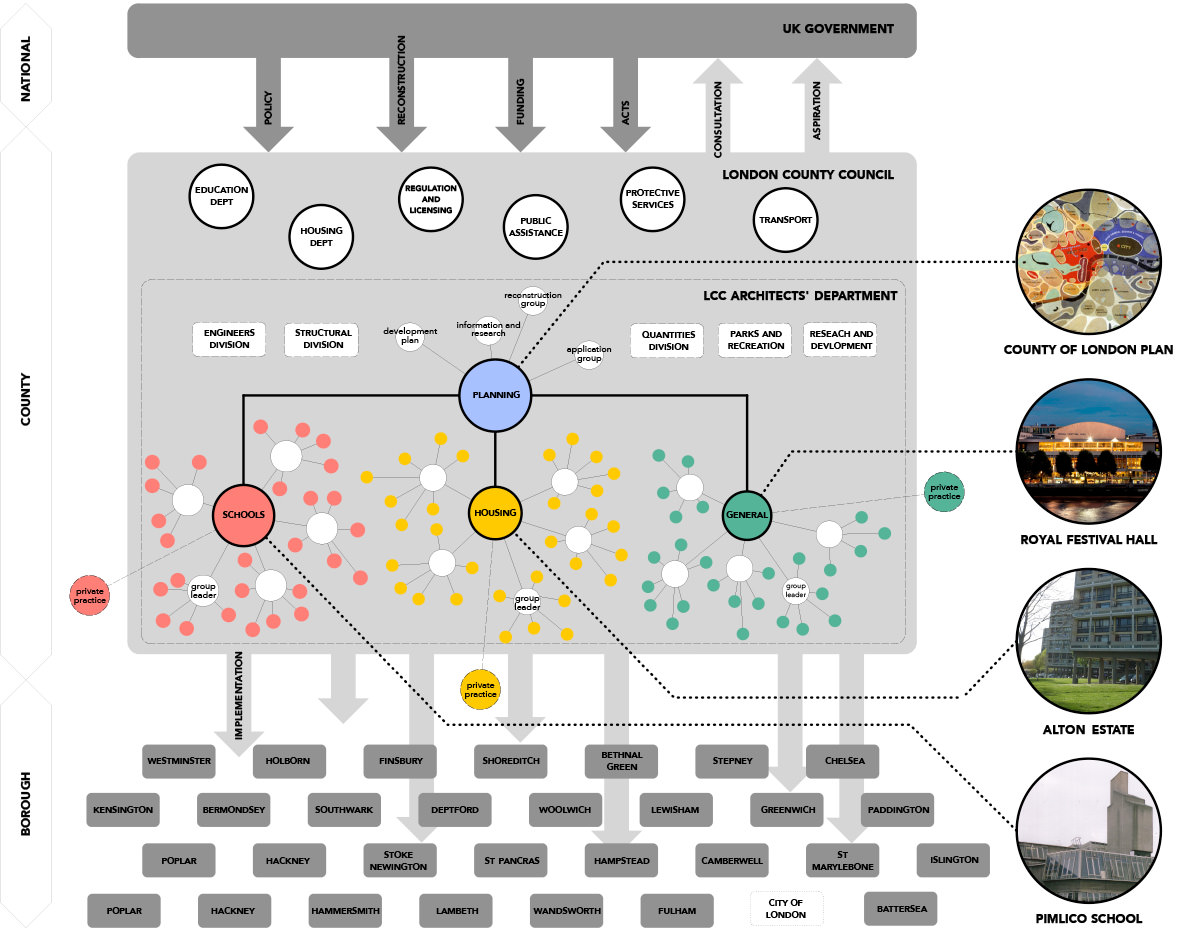

Being sandwiched between political intentions and local implementation, the architects of the LCC operated at a pivot point within the LCC’s operational structure – between city-scale aspirations and tectonic detail. The wider objective to improve smaller-scale local conditions meant that the neighborhood unit, its housing, parkland, schools, and transport networks could not be planned without consideration of the greater organism of the city. It was a system which worked both top-down and bottom-up; their soaring aspirations to build a new Britain holistically both enabled by much drier initiatives such as the introduction of Compulsory Purchase Orders, whilst also necessitated by local and national government Acts for Housing, National Health Service, and Education. Previous reports undertaken, such as those by the Ullswater Commission on London Government and Edwin Lutyens’ Highway Development Survey compiled for The Ministry of Transport only six years before, were considered too narrow in scope to provide a remedy to the county’s greater ills, but the County of London Plan sought to integrate solutions, linking housing, transport, industrial provision, education, leisure and cultural strategies. They also reached beyond London’s geographic borders rather than merely internalizing the issue, developing plans for the New Towns initiative at Harlow, Milton Keynes and (unsuccessfully) Hook with a view to improving the health of the urban environment and its residents by providing relocation strategies for 500,000 to 600,000 people. But such initiatives could only be made possible through the creation of sweeping transport links such as the cross-borough Westway and connections at the heart of the city as part of the newly nationalized railway network, requiring complicacy from the local councils over whose boundaries they ploughed as well as to the higher echelons of governmental power – these were not tentative steps to break free of the shackles which constrained the County, but an optimistic leap forward to a new utopia. Abercrombie and Forshaw’s introduction to the Plan identified this strategy of urban rehabilitation as a continuation of the means of serving the city as their employees had during the war, not only to defend its defining character, but to seek to right the wrongs being wrought against it from inside as well as out. While the Plan was conceived as a catalyst for legislation rather than operating within existing structures which may otherwise have constrained its scope, it identified and sought solutions for potential barriers – not just in the geographical and topological sense, but also the social, political, and financial ones. It was a complex, overarching, and potentially controversial strategy, yet one which was believed to be essential to Britain’s post-war rehabilitation. Being positioned at the crux of these intentions enabled the Architects’ Department to facilitate such aspirations in a manner which would not have been possible if – like the less prevalent form of private practice at the time – it had been dislocated from the mechanisms of politics, and the empowerment of economics and policy that this entailed.

In delivering the huge numbers of new and rebuilt public sector schemes required following the end of the war and necessitated by the ensuing population boom, by 1952–3 the Architects’ Department grew to become the world’s largest, with 1,577 staff including 350 professional architects and trainees. Support from the ordinarily segregated publishing, valuation, and engineering divisions was added along with conservational assessment and analysis via the Survey of London. The scale of their proposals – particularly for schools and housing as outlined within the Plan – enabled an open remit for commissioning furniture and component design and manufacture, all of which was undertaken in-house. Chief Architect JH Forshaw had realized the necessity of rigorous restructuring of the department in order to maintain an effective sense of operation over such a multi-headed beast, thus mirroring on a corporate scale the restructuring philosophy he had proposed in his authorship of The County of London Plan. The resultant approach of ‘group working’ created ‘streams’ of architects, each reporting up the chain to a core team of 12 to 16 within each Division, and then on to the Chief Architect, who could therefore have an awareness of interrelation of the many tentacles of implementation. The network of divisions dealing with Planning, Schools, Housing and General Works was essentially non-hierarchical, although the Planning Division had a pivotal role in operating between implementation and intent – a move which enabled a wider view of integration between proposals.

Yet while this structure gave a sense of overall coherency to the Department’s machinations, it also engendered a greater degree of autonomy to each sub-set, which generated a particular sense of freedom and experimentalism for which the Council became renowned. This freedom and autonomy would simply not have been possible in private practice, and it directly impacted the innovative, though at times naïve, nature of the architecture they produced. This experimentalism was further reinforced through the support of the Research and Development Department, which sought to bring a futurespective slant to how society could make better use of existing technologies – such as those for modular prefabricated construction – as a catalyst to break free of historic methods of production which were tied to old industries and outmoded ways of living. The lack of overall direction that resulted from such organization strategies is most evident in the East/West split of the Alton Estate in Roehampton, as the scale of delivering such a huge housing development necessitated splitting the work into two teams who each adopted a seemingly opposite stance: Corbusian high-rise to the West versus low-level vernacular terraces to the East; experimental concrete shells versus traditional brick construction; slabs versus points. Both differed radically in approach at every scale, from overall conception to the minutiae of tectonic detail, but all were developed under the umbrella of one Division.

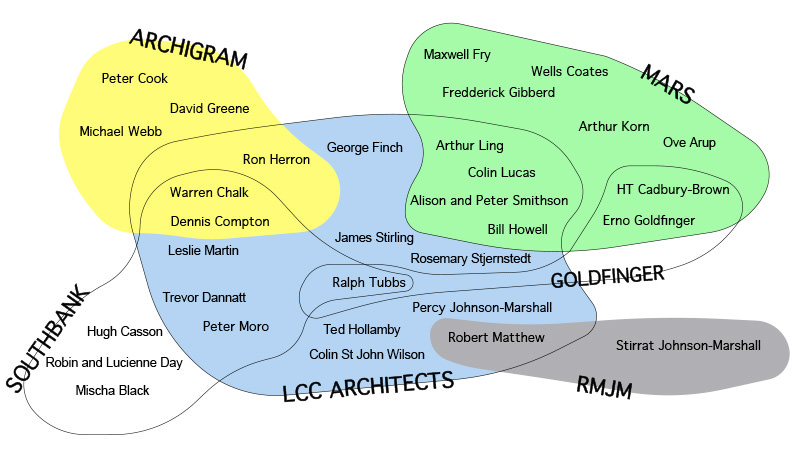

As a result, the Architects’ Department gained a reputation for its uniquely experimental and self-contained studio atmosphere, which gave its staff the freedom to create and to rethink, with the luxury of time and support for research. This environment was particularly attractive to new graduates, enticed by the potential for freedom for design and direct professional contact with their heroes such as Colin Lucas and Peter Moro – who had taught many of those recruited at the Council-run Brixton School of Building and the Regents Street Polytechnic, a hotbed for testing ideas in reinforced concrete and socially orientated design respectively – bringing with them novel approaches to what could otherwise have turned out to be very much run-of-the-mill projects. Among such students were Alison and Peter Smithson, Terry Farrell and Nicholas Grimshaw, Warren Chalk and Ron Herron of Archigram, and Bill Howell, John Killick, John Partridge and Stanley Amis of HKPA. These practices went on to define a national sense of Britishness within architecture, creating an architectural genealogy born from within the Architects’ Department at the LCC which continued its legacy even after the borough restructuring of 1965 which saw the LCC’s transformation into the newly designated Greater London Council (itself later abolished by the Local Government Act of 1985) with diminished powers.

The intention of this devolution was seemingly one of benign efficiency with an aim to reduce bureaucracy – the argument simultaneously being used for moving away from using architect-educated planners within the Council – dividing the LCC’s powers between central government and that of the Borough councils in order to diminish the middle tier of government. Yet parceling up and fragmenting the Council’s structure into Borough-sized chunks created a disconnect between overarching tenets of politics, education, and industry on which the LCC had thrived, and thus muted the potential for a rallying cry of aspiration for London as a whole, shifting its focus from overall control back to piecemeal considerations.

While in theory still practicing under the same title, the powers of the Architects’ Department were also dispersed in the wake of such disassembly; its capacity for implementation became too small relative to the growth of the city it now encompassed, with too large a remit to undertake the forms of experimentation for which it was once renowned, or to adapt to the many more varied local conditions required by the contrasting urban contexts in covering both Inner and Outer London.3 At the same time, the establishment of the South Bank Polytechnic moved the Brixton School of Building from its niche straddling politics, economics and practice, out into the realm of academia, and severing the direct links not only in terms of potentially employed students, but also in using the school as a testing bed for ideas. And thus, the unique network of influences was broken.

The component parts of these networks still surround us, but there is little suggestion of a structure with which to reassemble them. There is much in this year’s British pavilion about the absorption and continuity of history in the development of a British version of Modernism and in forming a sense of national identity, but like many of the contributions, there is little about the future of such a process, or the process for achieving such a future. Our predominant concern for the relative merits of architectural design based on aesthetic and functional assessment alone denies the lessons that could be learnt from this period in defining our identity as a nation. We’ve cultivated a tricky love affair within the profession of being utterly enamored with something we know is incredibly bad for us, given the public distaste for such concrete structures and slab housing. Through the psychedelic filter of A Clockwork Jerusalem, we are reminded of the dystopian cinematic context of Thamesmead, of the societal problems of schemes such as Milton Keynes, Robin Hood Gardens, and the Hulme Estate – issues which are subsequently held up as examples of when overly dogmatic architectural intentions were applied and proved too inflexible in adapting to changing socioeconomic contexts, and which ultimately failed under such strains. While we may not simply seek to emulate revered tectonics and forms in contemporary practice, we should heed the words of Banham, Barker, Price and Hall, who warned of the importance of looking back in judging whether what we planned when looking forward would be successful. The confluence of social, political, and economic systems that formed key factors in the genesis of these projects, and our role in addressing them remains an important consideration. As Bruno Latour observes4, this intertwining of culture, climate, economics, history and politics is fundamental to our understanding of any given situation in the field of ethnography (as well as in journalism), yet contemporary architecture is somehow thought of as predominantly self-referential. Architecture is undeniably developed as part of a complex system, which demands reconsideration as process rather than product, and the reassessment of professional boundaries. It was consideration for these systems – combining the roles of the client, regulator, consultant and architect – which afforded the freedoms of the LCC Architects’ Department after which we hanker.

While the state’s role in building our nation architecturally may seem diminished in the UK at present – being reduced to control and intention but with little influence upon the processes in-between – what opportunities does architecture have to reengage politicians and the public in a common vision, to inspire renewal and reengagement through collaboration and innovation in the wider sense? Can we re-assess not only architectural practice and the delineation of professional boundaries, but also how we build connections within the networks of economics, politics and social factors as part of the greater architecture of implementation? History has shown the importance of maintaining a constant balancing act between flexibility and structure, in order to reestablish a relationship between freedom and control – we cannot successfully cultivate one without the other, and we need both on which to build a future both as a nation and as a profession.

References

1. Reyner Banham, Cedric Price, Peter Hall, and Paul Barker. ‘Non-Plan: An Experiment In Freedom’ in New Society, March 20, 1969, 435–43.

2. P Abercrombie and JH Forshaw, The County of London Plan. First Edition. London County Council 1943.

3. Evelyn Dennington, Baroness Denington on GLC. London Broadcasting Company / Independent Radio News, March 27 1986.

4. Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993)