A City in the Making

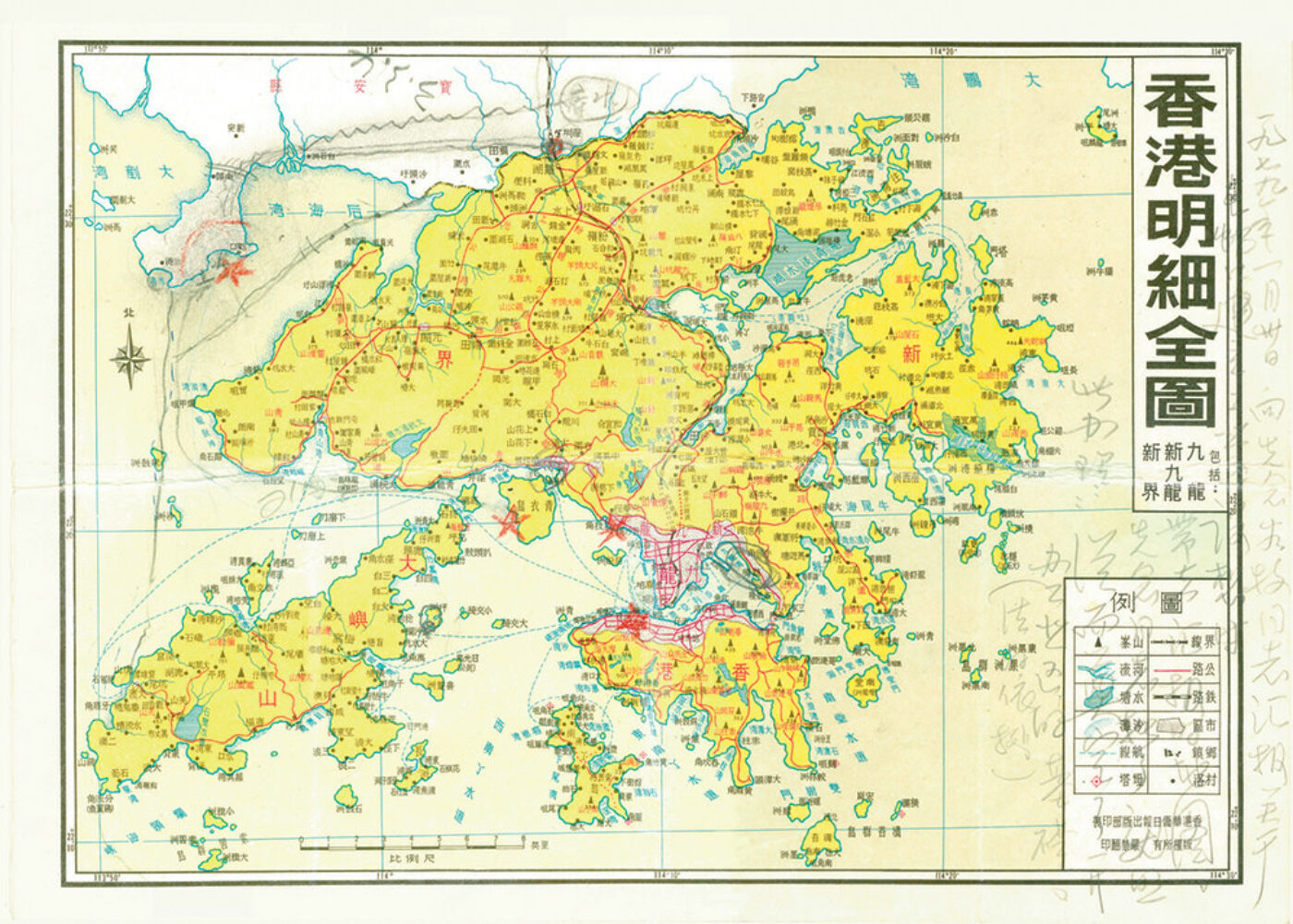

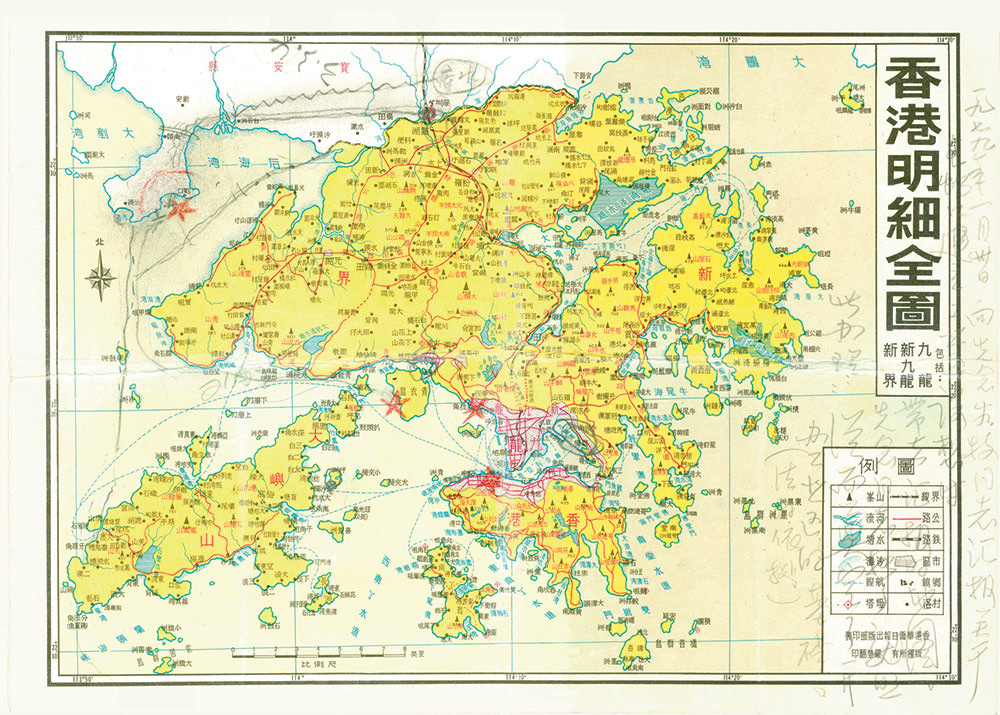

It’s rare that a city’s birth certificate survives, but here it is: a map of Hong Kong full of marks and notes. It is an intriguing document, but our attention should go to the upper left corner, where in the ‘white space’ of mainland China the Shekou peninsula is encircled as the new harbor and industrial location of what was to become the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone; conveniently situated and easy to control. The map with personal marks and handwritten notes makes history tangible. It all started with an idea and a location.

When a group of Dutch architects visited Shenzhen in 1997, the city was well underway – an urbanized area reaching from Shekou in the west up to Yantian in the east and beyond. A long ‘ribbon city’, draped along the border with Hong Kong. An impressive model showed the new center – the Futian district. Today it’s the location for the city’s major administrative functions, but at that time it was still a wasteland. None of the visitors believed that the model served more than a promotional purpose. The distance between the notion ‘city’ as we knew it and what we encountered was simply too big. For a westerner, it was a fascinating, yet a totally dystopian experience: driving for hours through urbanized areas of various densities and heights, with abundant empty spaces in between, possibly reservations for future development, but just as likely areas that hadn’t been touched by planning at all. Any sense of centrality or gravity was missing, although densities around Luohu, the old border crossing with Hong Kong, were higher than elsewhere.

At the time, Shenzhen was internationally recognized for its big numbers. It’s phenomenal growth rate and speed of development tickled the imagination. While Rem Koolhaas lectured about the speed of production in the Pearl River Delta – stunning his audience with calculations indicating that an architect in that area would have less than eleven hours to design a whole skyscraper – we were confronted with this practice for real. Inside a Shenzhen school of architecture, looking out a window, my eye was attracted by five apartment towers in the distance. They looked quite similar to a graduation project I had just seen. Asking the Dean about it I couldn’t stop myself saying: “That student didn’t go far for his inspiration”, pointing at the towers outside. “On the contrary”, the Dean replied, “those towers were built to his design after he graduated”. While young architects in the west would be really happy to have a villa extension or five row houses as first assignment, here a thirty floor multi-tower apartment complex seemed to be the norm.

Returning after sixteen years, the city has matured. The 1997 model was for real, the proposed center did materialize, and also on a more general level the city has become more normal, a bit easier to relate to. Easier, not easy, since structurally the city is an intricate patchwork of historic relations and autonomous developments, held together by the main road structure and metro lines. It is mind-boggling to realize that in a city of fifteen million, almost every building or piece of infrastructure is 35 years old at most. But looking around, there is a growing sense of history, a mix of older and newer, of well-designed and improvised parts, of decay and renewal that creates a sense of place.

And here the new story begins. Shenzhen was produced by borders, by drawing a line and defining a zone of exclusion. Yet its aim was and is to mediate between territories and in the long run to do away with the borders altogether – the Hong Kong border is to expire in 2047, finally integrating that territory in the Pearl River Delta megalopolis uninterruptedly. The city was created and built as a tool for a purpose, a production and prosperity machine, a commodity; now it faces the challenge to stay subservient to this political-economic agenda or start working on its own reality. Should the conclusion be that once this goal of balancing developments inside different parts of China (Hong Kong being one of them) and of China with economically more developed parts of the world has been achieved, Shenzhen can be discarded, dissolved like the inner border with China was gradually dissolved? To move away, follow the money, follow capital on its search for better profit, like factories in Shenzhen already do, moving to cheaper labor countries like Vietnam? Or should we conclude that Shenzhen has been animated successfully, that it has a soul that deserves fighting and caring for, a soul that will become more profound with age?

Asking the question is answering it. At least Shenzhen’s planning department did, when they launched this Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) in 2005. At first this may have looked like a branding operation. To make Shenzhen visible on the global cultural scene, a biennial seems the effective thing to do. Other port towns did. Rotterdam was not known for its cultural climate, nor was Liverpool. It is something to work on, with minor investment a lot can be done. The UABB could also be seen as the application of a by now well-known and tested redevelopment formula, deployed in almost every larger city in the world: attract a creative class of small entrepreneurs by offering empty industrial building stock for next to nothing, and witness a creative industry blossom, transforming the industrial production economy into a postindustrial service economy. One could even argue that the UABB is a local affair, that Shenzhen is taking care of its own problems and uses the biennale as a tool to experiment and kick-start redevelopment. All this can be said and all this is not untrue.

But it is fascinating to witness this transformation of an urban condition, the growing awareness and will to give direction.

Shenzhen is redefining its attractions, is redefining the way to go about it too. Potentially it is an example for other cities in China and beyond. That makes this UABB interesting on an international scale. No need to compare this biennale with Venice for instance; it is a different animal. In Shenzhen there is something at stake. The bigger plan is to synchronize with Hong Kong, the urgency is to reinvent the economic formula based on labor-intensive industrial production and upgrade to a service economy, the challenge is to create a city that sustains such transformations. Up to now the city could deliver demands, and accommodate needs. Now it has the chance to transform in something more permanent, more sustainable. That quest starts with this fifth UABB\Shenzhen, presenting an inventory of phenomena and an experiment with space. As its creative director Ole Bouman put it aptly: the biennale as risk.

This article appeared in Volume #39: Urban Border. Click here to buy this issue.