Last year, Felix Madrazo and Adrien Ravon led the ‘Ego City’ research studio at The Why Factory at TU Delft. It was one of a series of studios that explored the themes of density and desires. Ego City focused on the individual and ways to claim and create space. In doing so, it questioned traditional methods of using design to create a better future for all and probed the viability of post-design futures.

Arjen Oosterman: What was your ambition with the studio?

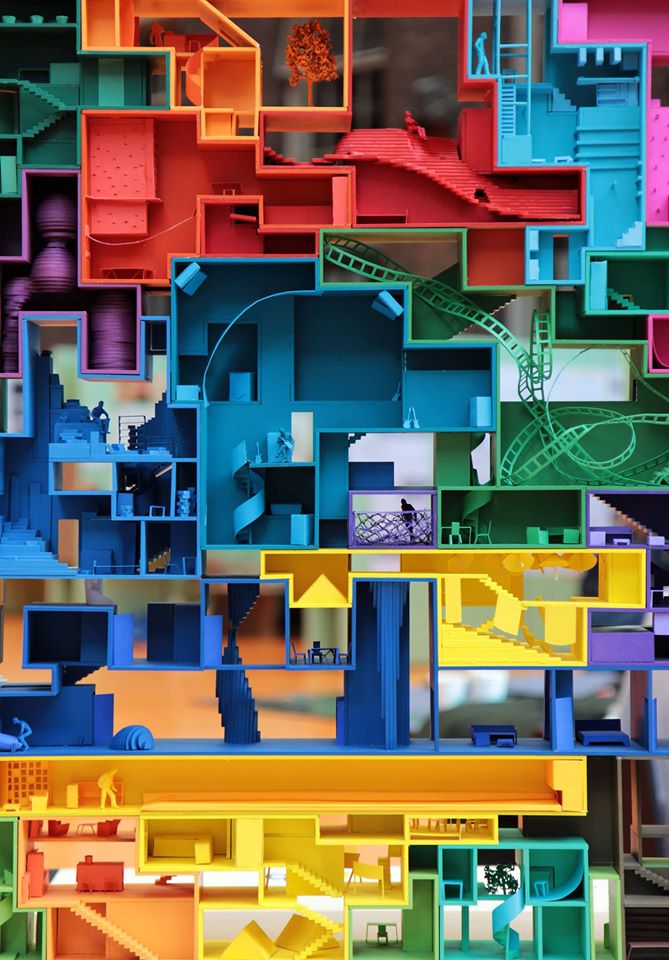

Adrien Ravon: The studio was called Ego City and started from egoism. Sixteen students were asked to search for (or construct) a client profile and then to formulate the special desires of this client. In doing so, they were asked to focus on one main feature, for instance horizontality, verticality, roof access, maximum view, and so on. We gave them an envelope, which was way smaller than the total volume of their dreams. We wanted them to discuss, negotiate, fight and find solutions to fit their desires in this dense, compact envelope. Can we reach win-win solutions, can we avoid compromise and can we design with a certain density while fulfilling maximum desires? That was the brief. We consecutively explored different ways of working. We started, for instance, with discussion, and

at a certain point we moved to the game solution to get away from discussion, because it was leading nowhere and taking too much time. So we decided to design a video game, such that all ‘characters’ could interact simultaneously and ‘play’ their desires.

So the studio manipulated the desires of individuals.

AR: It is about the malleability of dreams. You have this Dream House and we researched how much this can be deformed, shrunk, to the extent that future users would still be satisfied. So if you want a nine meter house, would you still be happy with four meters? Or how much would you be able to compromise?

Felix Madrazo: A bit of the ambition is to explore a way of interacting in which the architect loses control of key design decisions, and that opens the possibility for users to control the space. That immediately creates a problem. If that is the case, there will be conflict — the future inhabitant of the building will clash with his neighbors. The studio began there. It didn’t necessarily mean that the studio was controlled. This was the first time we did a studio that was not scripted, that didn’t end in one direction but with unpredictable results, because users interacted directly through software without much of the designer’s control. That made a big difference. Yet, we are still in a sort of beta phase; many things have to be improved. For instance, when the adopted user is old and demands silence, the player in our studio is supposed to represent that ambition. In reality this is very difficult, since representing someone’s agenda while playing can easily lead to deviations, even with the best intentions. For me, one of the most convincing players was a student who decided to play as himself. Potentially, that means that normal citizens can get involved in this way. That’s the bright side of it. Yet it is still rather early to know the advantages and shortcomings of this way of working. Normally, the client revises the stages of design and ‘corrects’ the direction of the architect in answering the client’s desires. In this case, there is no space for such revisions. You either trust the architect to play for you or you learn how to play yourself! I also want to return to the aspect of technology. In the beginning we didn’t have real interaction. We were going for a simulation of conflict. But because some of the students were really good at gaming and scripting, and we had the highly professional support of Arend van Waart from the Future Model class, we managed to develop these different techniques. The first exercise was a conflict simulation between two users. Both would say what they wanted and discuss. “If I have the balcony over here, you can have the living room over there”, and so on. And both would be very proud and happy to have reached this win-win situation. This was a very telling part of the studio, since it showed that everybody was very kind and tried hard to find a compromise between two users. But that was going against the brief of a city primarily based on

egos. So we created a rule to prevent this. No negotiation allowed, no compromise. Just ego. This led to the second phase of the studio where the students created four ways to address egoism, conflict and resolution. In my opinion, only one of them gave a smart answer to this constraint: the Blind Ego City. It means you have a space in the envelope and you try to conform it to your desires. But you don’t know what your neighbors want or are doing. You fight for your own space and everything else is black. This created the best results from all four programs. We always thought that jealousy and similar emotions make one more competitive and therefore more successful, but this assumption was proven wrong. Following your paranoia actually works best! [laughs]

So where did the project originate? A criticism, a desire?

FM: The grandfather of this studio was called Anarchy. We wanted to see how a city would evolve without government. In that studio one student made a proposal called Ego City, in which she proposed capsules for individuals that would never interact with the others. But that was completely designed. Next came a studio called Anarcity, which was more scientifically based on how citizens would react when government collapses. The students produced a filmscript of what people normally do when there is no water, no electricity. So for a long time we’ve been interested in exploring what would happen if nobody was in control. But it was difficult to do this convincingly. You can make a movie that looks perfectly real, but you cannot predict citizens’ reactions in real life.

Then we moved to a less complex scale, not a city, but anarchies in architecture, taking into account that the egoistic aspect was the most promising part of this. That was the start: the wish to simulate conflict and self-organization.

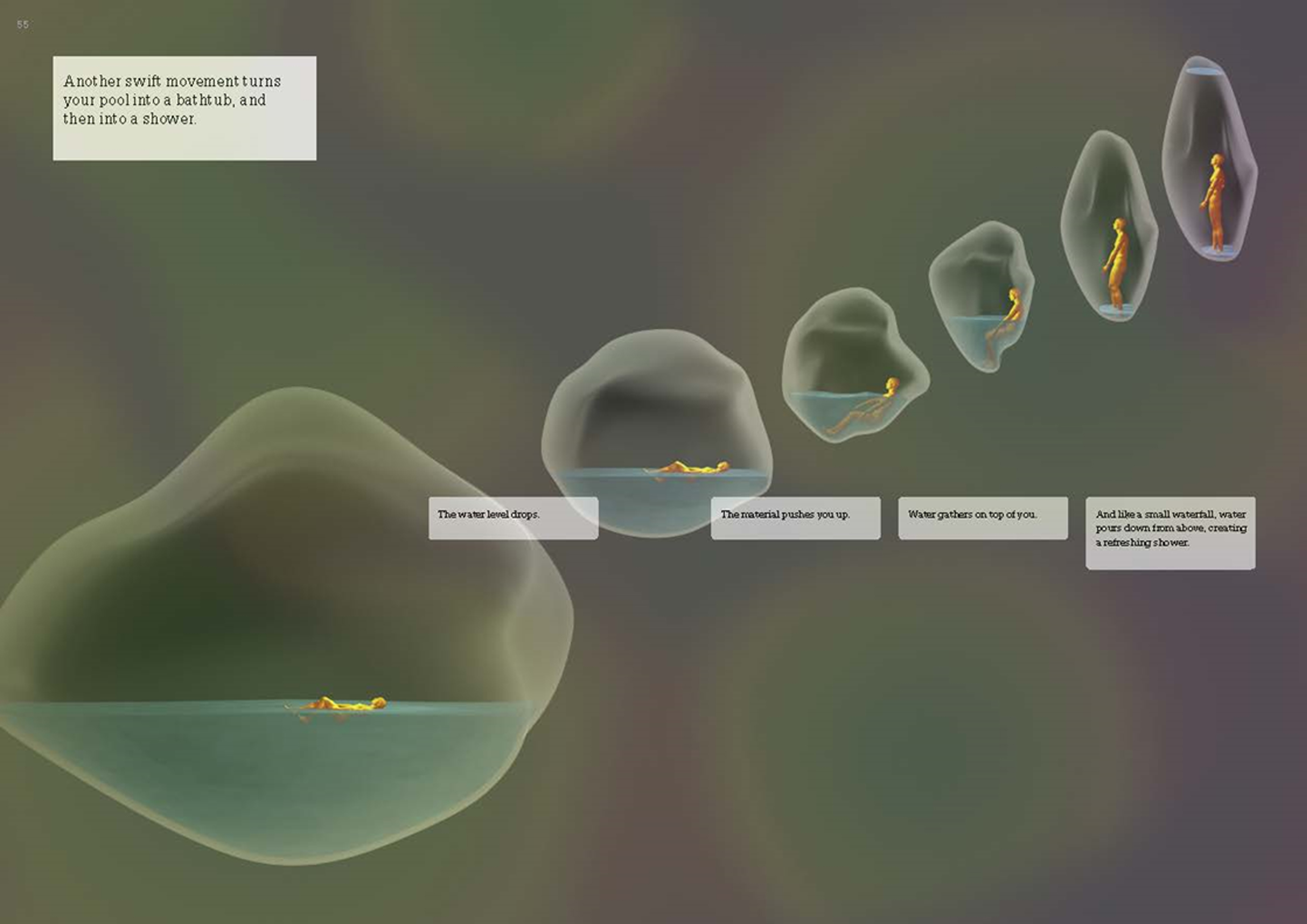

AR: Another project that inspired Ego City is one called BARBA, living in a fully transformable environment, in which we speculated on the future of our life and built environment if everything was made of nano, transformable material. What would happen if you lived in an environment that was completely malleable. You could be more ergonomic; your space would shrink if you didn’t use it. You could desire whatever you wanted, morph your own space, extend it, etc. until your neighbor came – and the wall in between is malleable. That resulted in a simulation.

FM: I’m forgetting an important inspiration: the house MVRDV did in Utrecht, together with Bjarne Mastenbroek. 1 That was based on negotiation and the win-win scenario that made everybody happy. The kind of thing we forbid the students.

What was the intention, your intention in the end, with setting this rule and theme?

FM: You see many people moving to the suburbs to build their dreams. In California, Latin America, Almere, everywhere. To a degree, anarchy remains unchallenged without a scarcity of space. We thought that the only way to achieve a proper understanding of conflict was through high density. So in a way, the question is how to realize these suburban dreams in a dense environment

AR: For the studio, we invited the students to go for more exuberant characters with weird desires, such as one who wanted a bowling alley. To avoid everyone wanting the same things. Because during an earlier studio, one student used Pinterest to analyze dream homes by looking at the images people post. For instance, the importance of the bathroom in relation to the rest of the images in a post. The material and color of these homes would change, but apart from that they were pretty much the same.

FM: Yes, that’s another difficult aspect. Many of us are happy with a pretty standard way of living, which sounds worrying: we are satisfied with a box flat and IKEA furniture.

That’s a house broker’s wisdom, right? They know it all. At least that’s what they tell us.

FM: But are we brainwashed, do we really love it? That’s also the question. What happens when we liberate the user to state what he or she really, really wants? We just don’t know. After we did Ego City, we did a second version in Chicago, sponsored by a developer. For him, the architectural results were not important. He only wanted us to develop further the sociological part of the interface of how users create this wish list. That is what he wants under control. Although he seems adventurous, he expects a catalogue, not something open-ended.

AR: During the second studio, we tried a questionnaire, asking the students “what would you like?” and giving them several options. This also led to houses that were more or less the same. So I think the first studio, Ego City, where we had the weirdos, the exuberant profiles, provoked them to dream a bit more.

FM: One thing we haven’t talked about is that we took the aspect of egoism to the extreme. So, the building doesn’t have any communal facilities. There is no core, no stairs, no elevator, a bit the opposite of the Soviet model [laughs]. Yet, paradoxically, the effort to put all these ego apartments together comes with a very collective feeling. Because the mutual fights are very intense, they couldn’t be closer together. Now they know their neighbors!

Can you tell us more about the role of the game technology that you applied? Was it a deliberate choice to go this way?

AR: Yes, we thought about this beforehand. And after some discussions, the students discovered that the use of game technology would speed up the process and save a lot of time, while helping them to be immersed in the process of negotiation and design.

FM: The fights were first conducted on paper, drawing manually. Then the students went to Excel and next to software, after they really understood the issue.

AR: It was always a ‘turn-based’ game, so the last one was always the loser. That’s why we’re looking at the possibility of having the interactions simultaneous and fast.

FM: You have to take into account that some participants end up with very bad housing. I don’t know what a developer can do with such places in reality. They were small, without much light, whereas the guys that played better would achieve really nice results. So I don’t know if in reality a citizen would dare to risk something as important as the house.

AR: On the other hand, what was quite interesting about the results was you would get unexpected shapes. You start with your dream home and end up with something quite different, still quite close to your desires. Really unexpected outcomes.

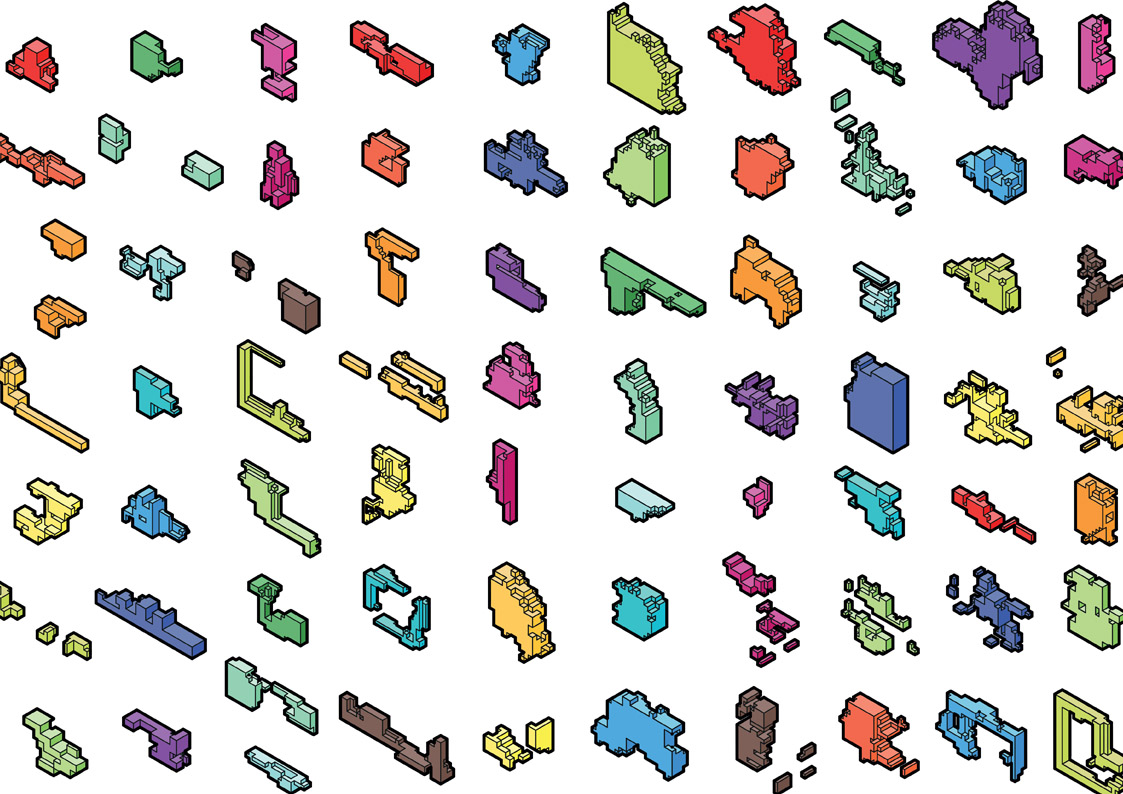

FM: Yet pixilated. That’s one aspect of the software used, a matter of resolution. It looked a bit like Tetris. The fights were on a small scale, but the computers had already crashed.

To summarize, you’ve been experimenting with the relation between density and dream. Is it also an experiment with the role of design?

FM: [after a long silence] The idea was that design would be pushed aside and taken over by a gut feeling of empowerment to conquer space. Design was the least important.

AR: The game software played the role of mediator. Apart from the software and the rules, we were not designing anything. The unexpected shapes that emerged from the negotiations were really the strong point. We also speculated about what would happen if you just had a questionnaire and then pushed a button, and the software would generate what you want. So the designer would become a spectator in the process.

FM: There’s an esthetic side to the game, in that the envelope is given by us, and it shows the outcome of the fights really clearly. It is not a normal building. If we did a normal building, that would not be so apparent. So there is an aspect of design involved, but marginally.

AR: We looked at different densities, and the higher the density the more complex and challenging the process gets.

FM: If I look at the last games that were produced, each player had control, like in a video game: they could go up, down, conquer space, fight etc. All of these tools are not necessarily design tools!

But does this touch upon redefining what the architect can or should do? Does it put into question, for instance, today’s architecture school curriculum?

FM: I think this has to come from society first. I don’t know if society really wants such a way of interacting.

This aspect really interests me. Your studio questions certain assumptions we’re currently working with in design. To what degree does it also question the definition of the architect and the way he or she works?

FM: The way the games we developed function (the fights and all) is still not ‘baby-proof’, but rather geeky. But it shows a direction developments may take. The moment this is accessible to everyone, the role of the architect may be seriously questioned. At least regarding the main design decisions.

AR: For this exercise, the students were stimulated to take some distance from the role of the architect as a mediator between clients and some constraints, and to leave that to the software, and also focus on other possibilities. We were not trying to find solutions, but more setting up possibilities.

FM: We let the teams explore freely. The students came up with four ways of answering the brief, four different scripts that had video game as interface. One was called The Automaton. For me that was the most interesting one, but also quite scary. The interface would map your desires and profile, and in the end the computer would create a kind of hierarchy in all of this as set-up to fight the other users. So the fight itself takes place without the interaction of the user. You just sit and watch the computer play for you; it’s exciting! But can the program really crack what you want…? What if you changed your mind on the way?

This is interesting in relation to the discussion on 3D printing. Because that very much stresses the autonomy of the individual. The promise of 3D printing is that everyone can be his/her own architect. Just push the button and the factory will produce the unique element you really want. It is another interpretation of dream. Whereas your software is going in the opposite direction: The program takes over completely and embodies your desires. Instead of you deciding, the system tells you who you are and this is what you want.

FM: That is one of the scenarios but it wasn’t appreciated that much. At the end of the process, the students selected The Blind from the four programs developed so far as the one to continue with.

AR: The Automaton proved too scary; you can literally leave the room and wait for the outcome.

FM: And the results were not better than those from the other, more human-controlled programs. So it showed that human interaction is still quite important.

But the project does question the role of the interface. So far we’re accustomed to using Rhino or Autocad, but these are no real interfaces but tools. And you’re moving towards a real interface reality, right?

FM: For us, doing things live was essential. Playing the game would have different outcomes each time. If you have Rhino and a client brief, you could do many shapes, sure. But in this case, what was put into question was: If you want to live together under dense conditions, you have to fight and give up isolation.

AR: If you look at other interfaces like Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram, it’s only about liking. You see only what you like.

FM: It’s not very engaging.

Adrien: You never get anything unexpected.

FM: That is similar to The Automaton. It produces what you like, but maybe not who you really are.

And if you relate this to what society needs or asks for. You were already confronted with the requirements of a developer. Are there more?

FM: We haven’t reached that phase yet.

AR: Most people’s desires we looked into in this Pinterest catalogue were about interior, material, objects and views, never about the space.

And in terms of benefits in relation to more classic ways of creating density? Because we ‘know’ how to do density, right?

FM: For me that was the most exciting part. We architects simulate density all the time and we love to simulate diversity within that density. But here you we’re actually making it. For me that was the most promising side of it.

Adrien: The studio focused on density and on diversity, but also on flexibility. If you have your dream home in a particular shape, what happens when you move out? That’ll be the subject for the next studio.

You say diversity is one aspect of the studio, how to create it. Can I rephrase this as a quest for the unexpected? To set conditions for the unexpected to happen?

FM and AR: Yes, absolutely.

FM: There were many unexpected outcomes. Also mistakes. If you look at the model carefully, you’ll notice gaps, spaces not claimed by anyone. Leftovers. So it’s not very efficient.

AR: We also experimented with the idea that some parts of the slab would be more expensive, because of the view for instance. Something we didn’t touch on during the studio was infrastructure: access, piping.

FM: As an afterthought, some ideas were produced, like add-on stairs. But the pipes were still an issue. I think we need new technology to liberate us from these constraints, the whole notion of the core.

Recently we had a discussion that, in addition to the bottom-up development, you need a sort of backstage to back up, with pipes and connections. I think we should challenge that part as well. No top-down at all. Let’s not fall back on the Centre Pompidou model.

1. ‘Double House’, Wilhelminapark, Utrecht, 1997. MVRDV + de Architectengroep