Why Build a New Town?

The following is an introductory article for Volume #34: City in a Box. You can read more about Volume #34: City in a Box here. You can buy a copy of Volume #34 here.

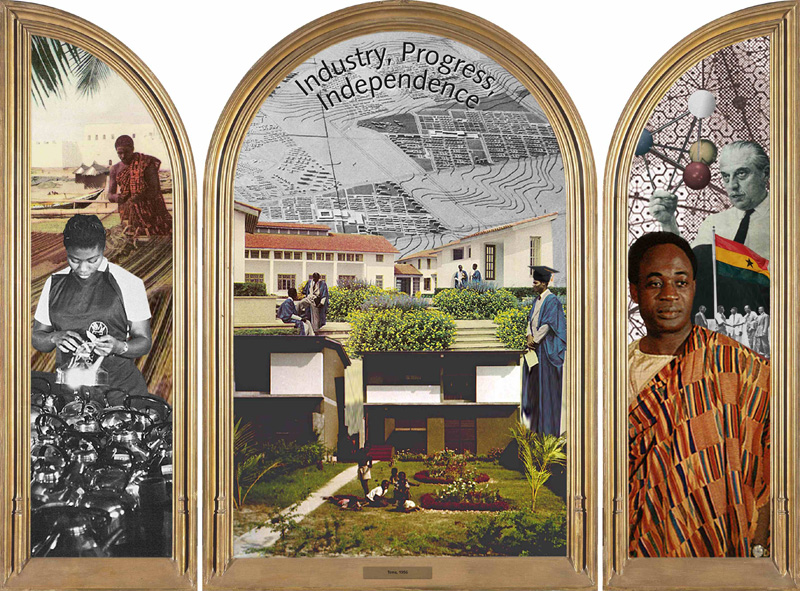

There once was a time when designing new cities was one of the most ambitious and urgent tasks for any urban designer and planner. The second half of the twentieth century saw a plethora of new models, ideas, and designs specifically geared towards the design of the ultimate ‘City of the Future’. The construction of entirely new integrated urban systems and the writing of technocratic and ideological books on how to build new cities culminated in the building of hundreds of New Towns in Western Europe, the US, and the new nation states of post-colonial Africa and Asia.

Now, for the last decades, the subject has all but disappeared from architectural discourse. In Western Europe the first and foremost condition for building new cities – economic growth – has disappeared; the extension and densification of existing cities has taken its place. Also the megalomaniacal belief in the future that reigned during the 1960s has vanished, diminishing the need for visionary urban utopias. On top of that, the New Towns of the postwar era have proven to be somewhat of a disappointment. Being seen as concentrations of social problems – living proof of how modernist planning has failed – they pose the question: is it even possible to create a city from scratch? All this makes it easy to proclaim that we should never again build New Towns.

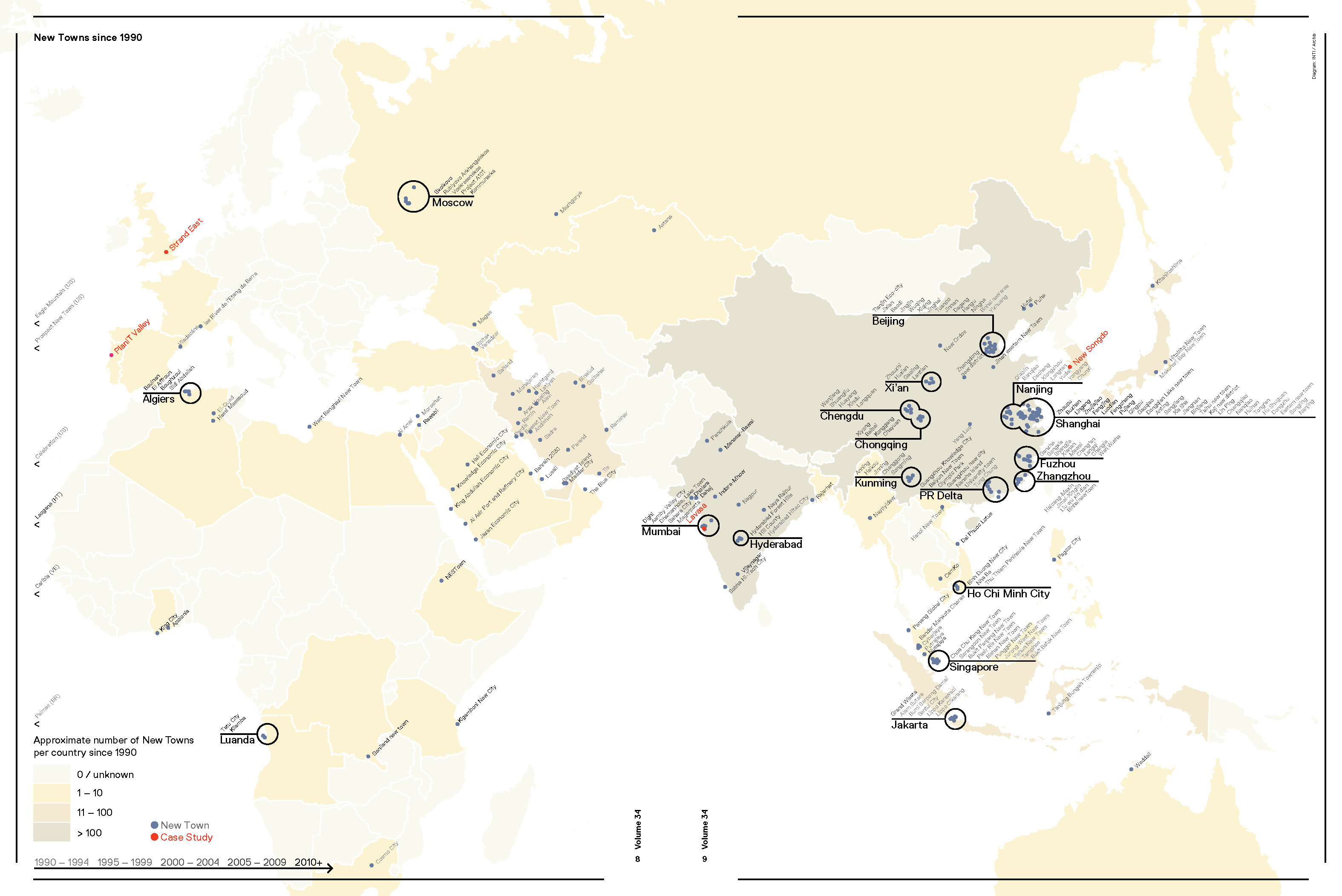

But still, they are being built. While relatively modest numbers of new cities are emerging in Latin America (where Hugo Chavez has accommodated his social housing program in New Towns) or Africa (Tanzania, Ghana, Angola), there is an astonishing series of huge new metropolises underway in Asia. While the numbers are hardly fixed, the predictions are that China will plan four hundred cities and in India it is estimated that two hundred cities are necessary to absorb the predicted demographic growth.1

Ironically, many of these cities are planned or designed by Western architecture firms, which leaves us with a paradox: because nowadays the designing of New Towns is no longer on the agenda in the West nor a part of our architectural thinking and urban ideology, the topic has all but disappeared from architectural education and publications. We might even go so far as to say that the architectural and planning elites, the ones who dominate the design debates, are in general not very interested in New Towns. In the twenty-first century, the architectural debate, when applied to urban matters, is much more animated by the massive unplanned migration to cities, by terrifying statistics and fascinating images coming from the ‘self organized’ megalopolises of the developing world. While big architecture firms are designing entire cities and constructing architectural icons ex nihilo in green fields, ‘their’ schools theorize mostly about the inability to plan urbanization, and offer up instead tactics of architectural acupuncture and bottom-up urban politics.

Social Democratic Cities

Thanks to the West’s twentieth century New Town boom, there already exists a huge body of knowledge concerning New Town planning – on both the designs and the mistakes that have been made – which can be useful for future generations of cities elsewhere. Indeed some of the reasons behind both waves of city building are comparable, then and now; the demographic growth, the rising middle class, and the exponential rise in the standard of living are equally present nowadays in Asia as in the postwar period in Europe. However, other circumstances are hugely different. In Europe there was an exceptionally large reliance on the part of governments in planning, modern architecture, urbanization, infrastructure, and the central role of the state in creating a new society. The construction of completely new cities was the most ambitious assignment of urban planners and architects, and the devising of new urban futures was the main obsession that occupied the theoreticians and avant-garde of architecture alike.

Examples of planning from this period are the New Towns built around London between the 1940s and 1960s; the Dutch groeikernen such as Zoetermeer, Spijkenisse, Capelle aan de IJssel, and New Towns like Hoogvliet and Lelystad; the German New Towns and large-scale expansion districts on either side of the Iron Curtain, such as Gropiusstadt in West Berlin and Marzahn in East Berlin; the hundreds of Grands Ensembles around the French cities that have been in the news in the last couple of decades only for their poverty, deprivation, and violence. There are also the Scandinavian New Towns, which are praised for their excellent design, but are now subject to social corrosion, such as Gellerup near Aarhus, Albertslund near Copenhagen, and Vällingby and Rinkeby near Stockholm. And there are the utopian icons, such as the Bijlmermeer near Amsterdam, Cumbernauld in Scotland, Le Mirail near Toulouse, and Louvain la Neuve in Wallonia, where the architectural avant-garde was given a mandate that would be inconceivable today: to build cities entirely in accordance with architectural concepts, based on an exceptional confidence in the ability of the design to determine the new urbanity and society.

This period of some twenty years also witnessed the high-speed development of the bureaucratic apparatuses that were responsible for the building of cities and districts and of the industrialization of housing. The large scale and the haste with which the urban expansion and the solution to the housing shortage were tackled led to blueprint planning with an urban model that was repeated all over the world and was based on concepts first developed in the Garden City movement and the British New Towns: the neighborhood unit as structural principle (repeated neighborhood units of 5,000 residents), a strict hierarchy in the spatial organization (street-neighborhood-district–zone-city) and in the infrastructure (from paths between houses to motorways). Moreover, the urban program was subject to strict zoning: schools, facilities, and businesses were allocated their own separate zone; a mixture of functions was regarded as inefficient and disruptive. The new city left its mark on the culture and economy of postwar Europe: as an object of fascination and speculation, but above all as a physical reality that determined the environment of an increasing (lower- and middle-class) portion of the growing population.

Neo-Liberal Cities

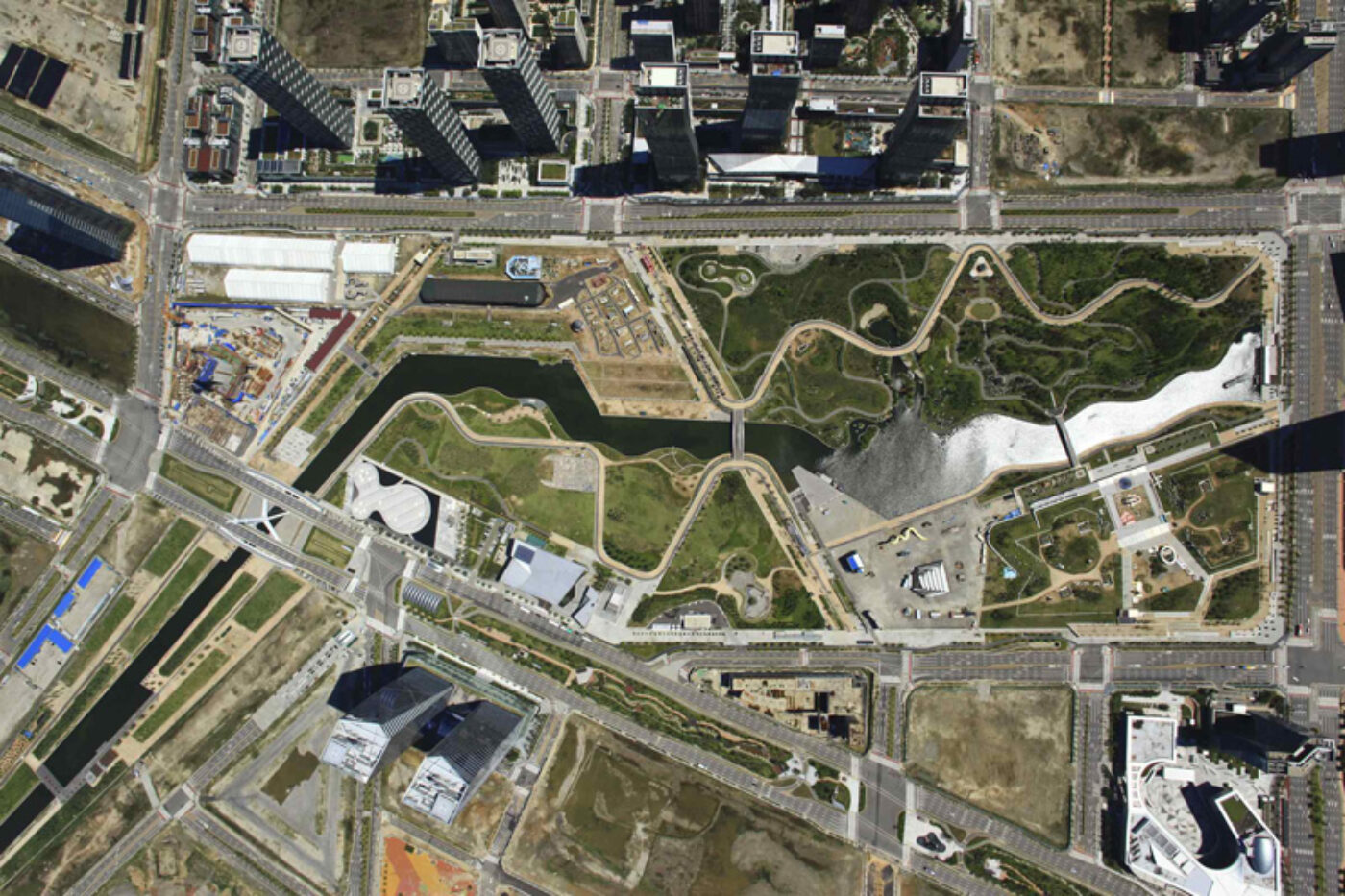

Now that economic growth has shifted to Asia, it comes as no surprise that the phenomenon of New Towns has also moved to this continent. With astonishing figures of GNP growth and a corresponding rate of urbanization, there is clearly a strong connection between the accelerating prosperity and the increasing amount of planned New Towns in Asia. However, it is a different connection than usually assumed. It is not the baffling amount of migrant workers moving from the countryside to the metropolis, who become the residents of the New Towns, it is the rising middle class. New migrants usually find a cheap room or apartment in older urban areas, in China for instance in the ‘urban villages’. These overcrowded high-density areas provide the affordable access to housing, restaurants, shops, and jobs. On the other hand, it is especially the rising middle and upper classes who are witnessing an exponential rise in living standards and who are able to move to New Towns. Here they find either the real estate they wish to invest in for reasons of speculation, or the quiet and safe living environment they prefer to the hustle and bustle of the metropolis. The New Town offers those who can afford it a suburban safe haven to retreat from big city problems. By attracting the affluent, one can assume it is also exacerbating tendencies of segregation in the existing city. New Towns are not so much the result of urbanization, than they are an escape from it.

The relation between New Towns and the rising middle classes also explains why there are less New Towns planned in Africa than could be expected based on urbanization rates. While Africa has the highest expectation in growth of urban population, there is relatively modest economic development in most parts of Africa. While there is also a relatively modest middle and upper class, there are few investors or developers interested in building completely new cities since there is only limited profit expectancy.

This demographic make-up hints at the most decisive difference with the European New Towns: while they were initiated, organized, and financed by (national) governments to contain the growth of the metropolis and to provide housing for all layers of the population, in the present generation of neo-liberal cities their role has, to a large degree, been taken over by large multinational enterprises, who work with different principles. The exchange of knowledge, the competition in global listings, and the ultimate authority over the plan now no longer rests with national government, but with separate cities and multinational corporations.

If we return to our comparison of the present generation of new cities to the postwar New Towns in Europe, major differences in the underlying conditions stand out. What took place in Europe was large-scale spatial development directed by the state, in which the New Towns played a crucial role. They were planned and produced where government, institutes, and organizations met one another. These diverse parties operated on the basis of a consensus on economic growth, cooperation, modernization, and regulation of urbanization. Added to this was an extremely complex and extensive civic society of public and semi-public organs, institutions, organizations, and housing corporations. Later, social themes such as emancipation and the equal distribution of knowledge and income arose as well. This is true to a greater or lesser extent for most of the countries of Western Europe in the period from 1950 to 1970.

A similar structure of cooperation, embedded in society and deploying long-term social agendas, is lacking in most of the countries of Asia when it comes to building and spatial planning. Moreover, while the West took almost a century to make the transition from a pure nineteenth-century industrial economy to the globalized market economy, the Asian countries are effecting this transition within a couple of decades.

Paradoxically, many of the new cities under development in Asia have been initiated and designed by Western firms. Contemporary offices like KCAP and Kuiper Compagnons from the Netherlands, Atkins, Foster, and HOK from the UK, GMP from Germany, and offices like SOM and KPF from the US, take up an enormous number of the jobs being offered by the most recent wave of New Towns built between Saudi Arabia and Korea, Azerbaijan, and the Philippines. Has Western planning become endemic in the East, just like so many other technologies originating in the West?

It would certainly seem so, if we see how closely some of the plans resemble typical modernist planning of the 1960s. We recognize the same system of neighborhoods divided by a system of parkways; we recognize the same zoning of functions and facilities over the map, strictly separating the housing from the industrial quarters; we recognize the same abundance of high-rise buildings and the fixation on car-based mobility.

But while the spatial translation of the program follows many principles of modernist urban planning, we also see that the current blueprint planning of New Towns has very little in common with the social engineering of the 1960s. At that time the social democratic governments had ambitions to create an open society by designing cities according to an open plan. The ambitions of the present Asian governments are very different. In spite of the parallels and rudiments of modernism, urban planning in China today is not similar to that in 1960s Europe. Above all, the master plan has become part of a much larger and more complex mixture of factors and instruments.

Western norms and values of spatial planning and urban design arose in a context shaped by social reform movements, such as the Garden City movement for good working-class homes and the Functional City. Moreover, World War Two contributed to the emergence of a large consensus on the need to involve the entire European population in a renewal of city and countryside based on democracy and modernity, in which the New Towns played a crucial role. As a result, spatial planning and public architecture in Western urban design are still associated with collective social values, reform agendas, democratization, and the construction of an open society. Whatever the nature and motives of urban design and planning projects may be in Europe today, the social, collective, and idealistic notions still play a role in our appreciation of them.

In Asia, where urban design and planning have a completely different background, these memories of the social roots of urban planning and architecture do not play any role and no lip service is paid to them. This may explain why the Asian New Towns can look so shamelessly elitist, so brazenly commercial, so shockingly superficial, so totally politically incorrect to Western eyes; Even when these cities were actually designed by Western offices.

The City as Commercial Product

Looking at the crucial role the new New Towns are playing in the economic development of the countries they are emerging in, it is clear that economic motives are the dominant factor behind most New Town initiatives. On a governmental level, they are usually part of a strategy to stimulate, diversify, and accelerate the regional or national economy. On the level of the developers, the new phenomenon is that the design, planning, and construction of a whole new city can be a profitable business. Social ambitions (in the sense of building for the entire population to bring about a combination of demographic or income groups) are lacking; there is hardly any social or affordable housing. Instead of a community center, there is a clubhouse next to the golf links. The present New Towns are populated by the middle and upper classes, while the lower income groups live in the old city or in self-organized cities, slums, and favelas. By default of their mortgage prices, these New Towns become a sort of resort for expats and the (upper) middle class. Made possible by its reduced demographic program, for the first time in history the city can be considered a commercial product.

The case studies selected for this issue are leading examples of the shift within urban planning towards the commercial sector, which becomes apparent not only in far away Asia but also in Western Europe. In London the development Strand East is being built with investments by Inter IKEA, putting the capital of the furniture multinational to use in an urban area, which will in its outcome still be very close to the urban models we are familiar with (inclusive, diverse, small scale). Yet the future city PlanIT Valley in Portugal is in its financial construction, organizational model, and design, a novel concept. The fundament of the city is its IT infrastructure developed by the initiating company Living PlanIT. The initiator considers the city to be a universal model town, an aspiration we haven’t seen since the modernist 1960s.

The Indian city of Lavasa is a completely privately developed, suburban city, which has grown into a hugely popular retreat for the growing middle classes from nearby Pune. Finally IT city New Songdo was developed and financed by American developer Stan Gale, coining its product ‘City in a Box’; taking standardization to the next level by putting the whole city on the market as a profitable, standardized product.2

While in the West usually these kinds of New Towns are regarded to be anomalies and are highly criticized for their architectural style, either European historic pastiches or generic CBD high-rises, and their urban plans based on car-dependent highway grids. Also the very relevant question is often asked: why build a New Town and not densify or extend the existing city? Are we still seeing an echo of the urbanistic ideas of the Garden City, building pristine safe havens in the countryside, at a proper distance from the dangerous and polluted metropolis? Without a doubt, the ghost of Ebenezer Howard is still very present. But also the element of governance is of utmost importance to explain why building a city from scratch is often preferred. Whereas in Western Europe the bureaucratic apparatus and institutions governing the cities, its planning, maintenance and management have been strongly developed over the course of the twentieth century, this is not the case in many other countries in the world. The metropolis in India, Tanzania, or Venezuela, to name only a few examples, is to a certain degree uncontrollable and cannot be shaped or adjusted according to the policymaker’s or planner’s will. A green field development is always a lot easier and presents fewer barriers to large-scale plans.

Also, the liveliness that in the West is seen as one of the main advantages of big city life, doesn’t necessarily count as a positive quality everywhere. The heavy pollution and over-crowdedness of many Asian and African metropolises makes its inhabitants long for a more suburban, quiet environment. They escape from the existing city to the New Town and welcome the ‘boredom’ that professionals in the West condemn these cities for. This is an important reason for the success of these new cities: they are competing with existing, historic cities and – different from their predecessors in Europe – they are winning.

We should look less at the deceptively familiar spatial structures and architectural content and more at the application of commercial, political, and financial mechanisms that are extremely exotic and strange by Western standards. The real dramatic change in the last decades is the huge diversification of actors who are responsible for these New Towns, the way the cities are programmed economically, and the way they are financed, maintained, operated, and built. What do these new parties desire? What is their vision of the future cities, their ‘products’? They finance, develop, and build new cities and make a profit. We know the why, now the question is: how do they do it?

This article is based on the introduction I wrote in cooperation with my colleague Wouter Vanstiphout for: Rachel Keeton, Rising in the East. Contemporary New Towns in Asia, (Amsterdam: SUN-INTI, 2011).

Notes

1. The sources for the amounts of new cities being planned are numerous and they all vary in their predictions. 400 Chinese and 200 Indian cities seems to be a conservative estimate.

2. On the financing of New Songdo: Stan Gale personally invested 100 million dollars and secured loans in excess of 35 billion dollars from Korea’s banks and its biggest steel company, POSCO E&C. The project eventually materialized as a 70 percent to 30 percent joint venture between Gale and POSCO E&C. See: R. Keeton, Rising in the East. Contemporary New Towns in Asia, (Amsterdam: SUN-INTI, 2011), pp. 312-313.