by Léa-Catherine Szacka and Luca Guido

The Biennale hasn’t always been the kind of neutral platform it purports to be today. In the 1970s, under the direction of Carlo Ripa di Meana, it broke off into a radically politicized agenda, explicitly addressing the nationhood and politics of three be-leaguered countries: Chile, Spain, and the former USSR. As Léa-Catherine Szacka and Luca Guido write, the exhibitions were transformed into a political device, a crucial apparatus for public confrontation.

Politics in art is neither to consent nor dissent, but rather to carry out those structural transformations within art, which politics carries out in society.

Giulio Carlo Argan, 1977

The political and cultural scene that took shape at the end of the 1970s, especially in the con-text of the Venice Biennale, is of extreme interest, for it was in those years that the Venetian institution echoed the hot-test topics of the time. It did this by becoming an experimental work-shop in which ideas, protest, and a culture of dis-sent joined together in an effort to challenge traditional modes of display. In particular, the theme of democ-racy was chan-neled at the Biennale, transforming the exhibition into a po-lit-ical device, a crucial apparatus for public confrontation.

Following the disruptions of 1968, the Venice Biennale proposed a new format for the institution and started a cycle of initiatives held under the auspices

of the new ‘democratic’ statute (1973), developed to replace the 1938 ‘Fascist’ one. Before this reform, only monographic exhibitions, as well as an anachronistic sales office and a division between painting and sculpture underlined by the different Grand Prizes for sculptors and painters, characterized the Biennale. This old static situation was thus overturned by some of the provocative ideas of the Biennale’s new president, Carlo Ripa di Meana, an ambitious and charismatic exhibitionist, who was later elected a Member of the European Parliament for the Italian Socialist Party(PSI).

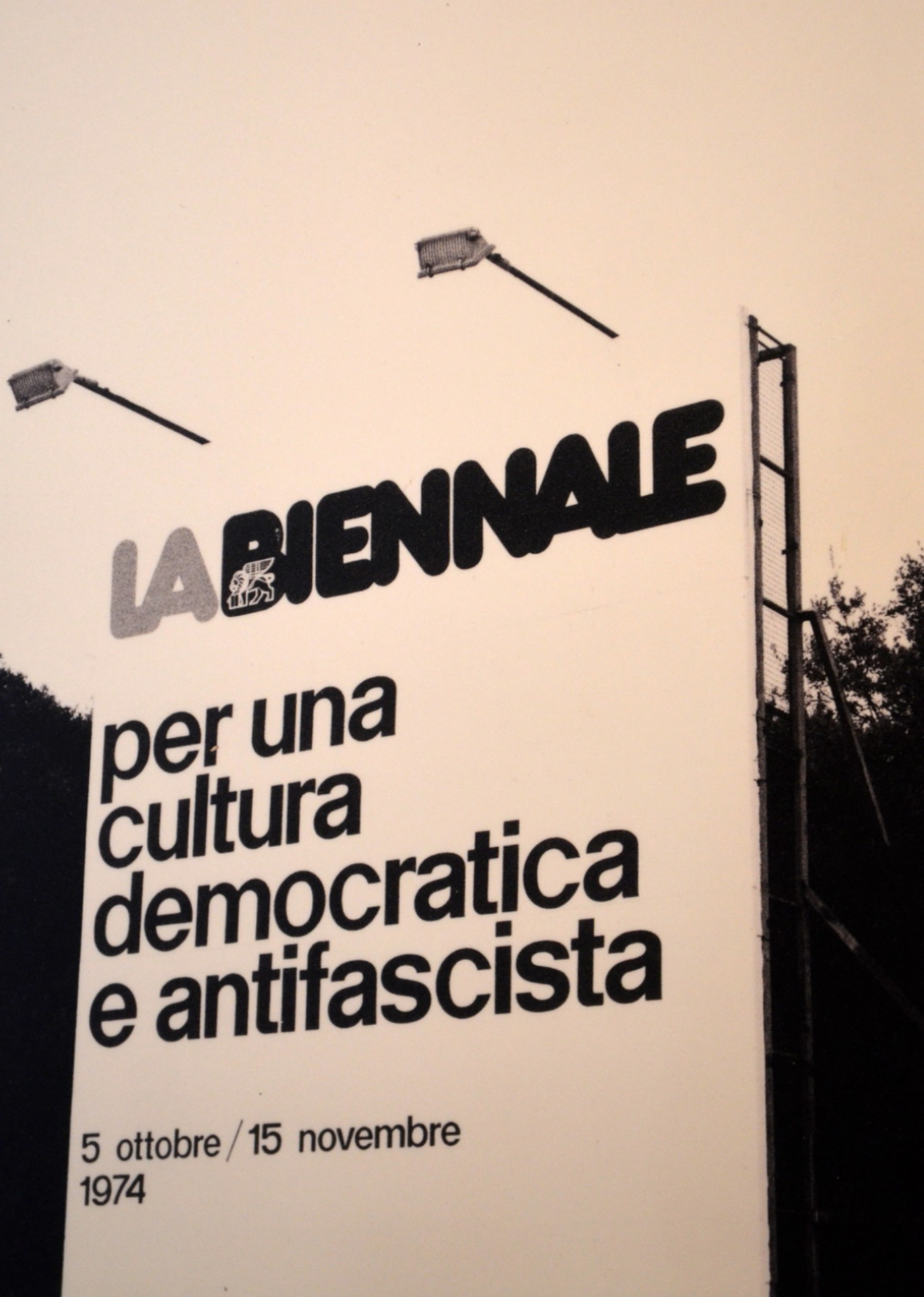

During the quadrennial period of 1974 to 1977, the Venice Biennale temporarily passed on celebratory exhibitions in favor of a thematic approach, which included crossovers of the various disciplines (art, cinema, and theatre). Called ‘Biennale per una cultura democratica e antifascista’ these exhibitions were dedicated to the struggle for democracy, and acted as battlefields, giving voice to a different meaning of the nations involved: political incorrectness and provocations were used to promote an unofficial culture paired with an unauthorized representation. By involving the culture of dissent of the newly shaping nations, the Biennale attempted to con-tribute to a growing diffusion of demands for freedom and independent expression. In doing so, it imagined and prefigured how some different countries should be represented, beyond official and diplomatic relationships: First, in 1974, a condemnation of Chile’s dictatorship; Second, in 1976, a celebration of the post-Franco Spanish democracy; And finally, in 1977, the glorification of the Soviet Union’s non-aligned artists.

The examples discussed below show the precedent of the Biennale as a force that attempts to bring new countries (or, here, new democracies) into the limelight. Beyond questioning how the Venice Biennale and other similar institutions can contribute to nation-building, this essay wonders if and how the Biennale has an impact on political systems and societies in general. In other words, can an institution dedicated to artistic production and display contribute to the building of a culture of dissension, while at the same time associating dissent to an inner national reality?

‘Freedom in Chile’, 1974

The 1974 edition of the Venice Biennale was officially launched with the event ‘Testimonianze contro il fascismo’, on October 5th in the Sala dello Scrutinio at the Ducal Palace and in the presence of Hortensia Allende, widow of Salvador Allende, Chile’s defeated president. This meeting dedicated to “analyzing the structural elements of Fascism, on a scale both national and international”, took place just a year after the bloodied experience of the Chilean coup d’état, a watershed moment in the Cold War. On September 11th 1973, General Pinochet, with the help of the CIA, brutally overthrew the socialist President Allende, repressing left-wing political activities. A poignant case of repression of a democratic system, the coup had a tremendous impact internationally and especially in Italy.

That year, Meana had decided to dedicate the entire edition of the Biennale to Chile setting up exhibitions and events in every part of the city and its industrial suburbs. The multidisciplinary cycle of events entitled ‘Libertà al Chile’ (Freedom in Chile) was a large cultural protest against Pinochet’s dictatorship. It included cinema (with a film section dedicated to the Unidad Popular government and the events preceding the coup); music and theater (with a series of theatrical performances and concerts of experimental Chilean and folk music); as well as visual arts (with an exhibition of more than a hundred Chilean posters, dating from 1970 to 1974, and exhibitions of large-scale photography on panels). Finally, Chilean painters of the Brigada Salvador Allende, under the guidance of artist Roberto Sebastian Matta, created a series of Murales in Campo San Polo, Campo Santa Margherita, and at the Arsenale, and the installation entitled Angel atacado por los United Snakes of America. By being boldly provocative and political, ‘Libertà al Chile’ announced the new direction taken by the Venice Biennale.

‘Homage to Democratic Spain’, 1976

Following the experience of 1974, the Biennale continued to express its solidarity with forces fighting for freedom by devoting its 1976 program to anti-Francoism, in ‘homage to democratic Spain’. In preparation for the event, Meana traveled to Paris to meet Santiago Carrillo, secretary of the Spanish Communist Party in exile, and to explain to him the main line of the program ‘Spain 1976’.9 The event was launched on July 17th just a few months after Franco’s death and exactly forty years after the start of the Spanish Civil War. During an official ceremony held in the Sala dello Scrutinio of the Ducal Palace, Mayor of Venice, Mario Rigo, “underlined the un-equivocal choice of the new Biennale to open the dis-cus-sion on Spain at a time when the peace and security of many nations [were] deeply menaced.”

The main exhibition of that Biennale, ‘Spain – Artistic Avant-garde and Social Reality 1936 – 1976’ was held in the main pavilion of the Giardini. It documented the path of Spanish art during the last forty years and analyzed ‘the connection between artistic expression and events occurring during the 1936-1976 period. Other smaller exhibitions such as ‘Spain 1936-1939: Photography and Information on the War’ at the Academy of Fine Arts were held in connection to the theme. ‘Spain, Forty Years After: Autobiography of a Civil War’ was also organized by the cinema section at the Palace of Cinema on the Lido, while democratic Spain also constituted the nucleus of the 1976 theatrical program of the Biennale.

It was reported that ‘Homage to Democratic Spain’, and especially the exhibition ‘Spain – Artistic Avant-garde and Social Reality 1936-1976’, was “very success-ful in the eyes of the specialists, the critics, political perso-nal-ities and a composite public which was both attentive and jointly responsive.” After years of dictator-ship, the exhibition marked the beginning of a new era and was a real tribute to all the people assassinated during Francoism.

‘Cultural Dissent’ in USSR, 1977

Between 1975 and 1977, numerous exhibitions hosting the works of ‘unofficial’ Soviet artists were held in major international capitals, including Paris, London, Washington, and Berlin. In Italy, the culture of dissent found expression at the Venice Biennale. All these events were direct consequences of the Helsinki Accords, a document that became the legal foundation for many initiatives of cultural dissent, involving their respective nations in the process of recognizing fundamental human rights.

By the summer of 1976, the Polish ‘June protests’ proved a significant episode of popular discontent, the forerunner for the climate of reform led by Solidarnosc in the 80s. In the same period, the way was paved for Charta 77, the document drawn up by Vaclav Havel and other dissident Czechs, which caused an international sensation following the arrest of the Plastic People, a rock group involved in a process encouraging cultural insubordination.

The territory of political and diplomatic oppositions moved to the cultural field and effectively contributed to the diffusion of demands for freedom and independent expression. In this context, the idea behind the Biennale of Dissent blossomed when, on January 25th 1977, Meana declared his intention to the Corriere della Sera to present the board with a proposal of conferences and exhibitions on cultural dissent in the Soviet Union and in Eastern European countries. For Moscow, this decision was seen as a provocation, undermining once and for all the relationships struck up with the Soviet Union during the preceding years. The question had now become a matter of state, as well as a diplomatic problem. After the resignation of the Biennale’s sector directors Vittorio Gregotti (art), Luca Ronconi (theater), and Giacomo Gambetti (cinema), new curators for the show were hired: Jirì Pelikan, a Czech activist; Antonin and Mira Liehm, cinema critics; and Gustaw Herling, a Polish author and essayist.

On November 15th 1977, after various polemics from the Soviets in reaction to the international presentations, and after boycotts by many Italian organizations and intellectuals, the Biennale of Dissent opened in the hall of mirrors in the Napoleonic Wing of the Correr Museum in Piazza San Marco with an underground, video-recorded message from the Russian scientist Andrej Sacharov, who had been denied a visa. The evening saw the screening of the film by Costa Gavras The Confession [L’Aveu, 1970], inspired by the life of Arthur London, with London in the room.

A large review of dissident art by Enrico Crispolti and Gabriella Moncada entitled ‘The New Soviet Art: An Unofficial Perspective’ was set up in the Palazzetto dello Sport dell’Arsenale. Alongside this main show, a smaller display on the clandestine and self-produced press, ‘Samizdat’, opened at Correr Museum. Hundreds of people were involved, and dozens of speakers and intellectuals took part in the Biennale of Dissent and its numerous events. Unfortunately the artists involved didn’t get a real international appreciation in the following years.

Today, the Venice Biennale seems to have gone backward, closer to the institution that, at the end of the 1960s, was criticized and ignored by the new generation of artists and students. Indeed, even if the Biennale is occasionally punctuated by rare and relatively unnoticed eruptions, protest, political commentary, or critical prac-tices in the form of political and spatial dissent, it resem-bles more a perfect globalized platform aiming to promote books, web sites, research projects, and so on. It was during the 1980s that the international exhibitions changed direction, shifting the research interest to objects and ruling an end to politically and socially engaged art and architecture.

This year however, the Golden Lion was awarded to the Korean pavilion, underlining the political situation of a country that can be seen as the last remnant of the Cold War. ‘Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula’ curated by Minsuk Cho together with Hyungmin Pai and Changmo Ahn, aimed to demonstrate the potential of a unified Korea by bringing together almost forty pro-jects from each side. By engaging both North and South Korea, the curators of the pavilion have tried to bridge two op-posite political and economic systems normally in conflict with each other – a gesture considered

as one of the most politically ambitious projects at this year’s Biennale. Yet, does this pavilion really express a geopolitical issue? Or, does it simply present a radical-chic topic without truly establishing a provocation or a concrete proposal?

In the 1970s Carlo Ripa di Meana and his acolytes marked a major blow by proposing the cycle of ‘Biennale per una cultura democratica e antifascista’, a series of provocative displays meant to, if not change the world, at least carry out a complete reform of the by then out-dated cultural institution that was the Venice Biennale. Yet, were Meana and the Biennale truly acting as an agent provocateur for democracy? If the impact of such an operation over the course of democracy is difficult if not impossible to assess, we can say that this operation was all but a simple altruistic venture. Indeed, at the time, the Biennale board was an expression of Italian parti-toc-racy. It was ruled by the PSI, a political party that was supporting new perspectives while taking its distance from Italian Communist Party (PCI), trying to use cul-tural issues in the political debate while embarrassing the part of the left movement close to Russian communists.

With the rise to power of their party secretary, Bettino Craxi, the Italian socialists gave full political sup-port to Liberal Socialism as they began to withdraw from Marxism. In fact, Craxi’s guidelines envisaged both Liberal policies and a transversal, cultural approach, which aimed to use the media to exploit the outcomes of some foreign political movements (both from an anti-Fascist and anti-Communist point of view) by diverting to a series of foreign organizations illicit funds, which later led to the complete disappearance of the PSI from the Italian political scene. The inspiration behind the PSI and its subsequent key role in the government essentially mirrored contemporary European trends.

While playing the agent provocateur, the Biennale’s real innovation was to propose a postmodern formula that was conceived to display and multiply the communication power of the artistic presences in specific situations. And this was certainly the legacy of Biennale during 1970s.