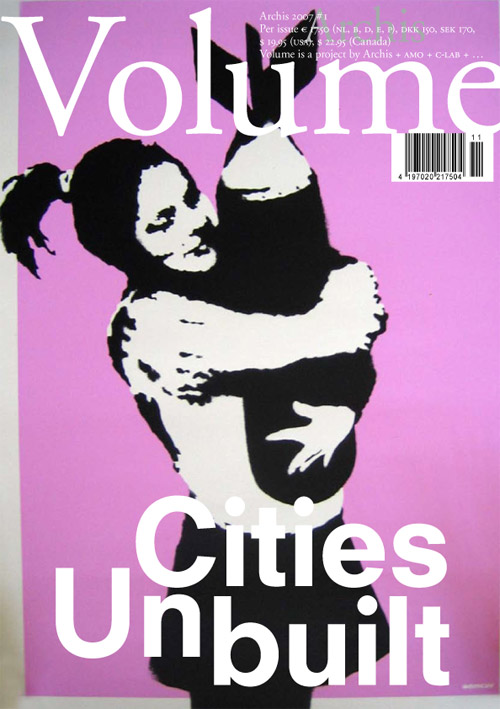

Volume #11 — Andrew Herscher: Warchitecture / Post-Warchitecture

2015 marks Volume’s 10th birthday. The coming weeks we’ll republish our readers’ favorite articles. If you feel tempted to highlight yours with a brief motivation, please send an email to 10years@archis.org.

“I would like to recommend the essay by Andrew Herscher about his work from Volume #11, Cities Unbuilt. I find his investigation into the violence conducted against architecture in the Balkans during the Yugoslav wars both inspiring and ground breaking. So is his practice, a two-person NGO that managed to produce reports that were used during the Milošević trail at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The relations between architecture, space, politics, forensics and crime has never been so direct and revealing.”

Malkit Shoshan is an architect and founder of the think tank FAST. Her work explores spatial design, politics and activism. She’s a regular contributor to Volume. Her latest research is on the landscape of war and peace. The part focusing on peacekeeping missions and their legacy was published in Volume 40: Architecture of Peace Reloaded. She’s currently based in New York.

During the war years of the early 1990s in Bosnia and Croatia, a unique sort of violence was thought to have emerged, a violence that was aimed precisely at architecture. The perpetrators of this violence termed it either a militarily necessity or collateral damage, both terms that legitimate destruction according to the reigning rules of war. The victims of this violence, however, termed it a destruction that was impossible to sanction.

In an exhibition held in Sarajevo in 1993, the targeting of architecture during the city’s siege was named ‘warchitecture.’ This concept provides a new category to understand the destruction of architecture during war and other forms of political violence. On one hand, warchitecture poses an enduring phenomenon in a new way. Buildings have, of course, been damaged and destroyed throughout the history of warfare. As warchitecture, however, this violence is framed not as a marginal or exceptional form of violence, but a systematized and potentially crucial aspect of warfare. On the other hand, warchitecture also Marks the emergent re-territorialization of war into novel forms of urbanized violence. In new urban wars, such as the wars in the former Yugoslavia, regional, national and transnational dynamics were transposed onto the very streets and buildings of cities. In warchitecture, the boundary between war and architecture is negated; war becomes a form of unbuilding and thus enmeshed in the spaces, ambitions and processes that architecture is typically thought to manage.

The following is a documentation of some dimensions of warchitecture and postwarchitecture in Kosovo. This documentation includes several distinct episodes of violence and counter-violence: the counter-insurgency and accompanying campaign of ethnic cleansing waged by Serb forces against Kosovar Albanians in 1998–1999; the NATO bombing of Serbia in the summer of 1999; and collective violence waged by Kosovar Albanians against Serbs from 1999 to the present. Most generally, this documentation reveals a bifurcation in warchitecture, with one version – that practiced by NATO through aerial bombardment – referring to a form of violence that targets buildings instead of human beings, and another version – that practiced on the ground by military, paramilitary and informal forces – referring to a form of violence that targets human beings through targeting their architectural surround.

At the same time, a documentation of warchitecture also contextualizes the Kosovo conflict in distinctive ways. One contextualization reveals that neither of the primary ethnic communities in Kosovo maintain a monopoly on violence against the architecture of the other. A more profound contextualization recognizes that concepts of ethnicity do not stand before and outside violence inflicted in the name and on behalf of an ethnic community. In other words, ‘ethnic violence,’ of which violence against architecture forms a prime example, is not the product of a static and homogenous ethnic community, but a performance of ethnicity, a performance that gives cultural meaning and social value to ethnic identity. Warchitecture, then, is not so much a product of ethnic violence as a means of ethnicizing violence in the first place.

Counter-Heritage

The architectural targets of destruction in Kosovo are typically narrated as the ‘heritage’ of the communities that identify with those buildings. However, it is destruction itself that often endows buildings with historical

significance. The targets of warchitecture, therefore, comprise counter-heritage: architecture rendered historically valuable by virtue of the violence inflicted against it. In this section, the various modes of destruction pursued by the protagonists in the Kosovo conflict are distinguished and compared, setting up new ways to understand this destruction as a cultural practice shared across otherwise antagonistic and separate communities.

Languages of Damage

Violence against architecture is, among other things, a form of communication that enlists architecture as its medium. In this sense, violence does not simply damage or destroy its targets, but also endows those targets with new social meanings. The communicative function of architectural violence is foregrounded when that violence includes graffitied messages. In Kosovo, graffiti frequently accompanied damage, elucidating the audiences and contexts of that damage. In this section, an index to graffiti accompanying damage in Kosovo is presented; the first half translates Albanian graffiti written on Serbian Orthodox architecture damaged by Kosovar Albanians in 1999 and the following years, and the second half translates Serbian graffiti written on Islamic architecture damaged by Serb military and paramilitary in 1998-99.

Live Destruction

Destruction in Kosovo was a subject of obsessive photographic attention by the very people and institutions who inflicted it. Understanding photography as an important technique of self-fashioning, this attention reveals the complicated relations that obtain between identity, space and violence: identity can be formed both by photographing a visit to a landmark or a landmark’s destruction. In this section, three sets of images are presented and compared. One set is taken from a video shot by a NATO ‘smart bomb,’ during NATO’s bombing campaign against Serbia in the summer of 1999. A second set of images is taken from

a roll of film shot by a Serb paramilitary in Kosovo during the summer of 1999. A third set of images is taken from a photo gallery posted on the internet by a Kosovar Albanian Photographer after a riot in March 2004.

Post-Archive

The Lebanese writer Jelal Toufic has noted that there are two kinds of catastrophes: one kind that can be read about in archives and another kind that destroys archives themselves.

The Kosovo conflict produced the second kind of catastrophe, as archives were among the key targets of destruction. This section documents publications about destruction in Kosovo that were produced in the wake of the destruction of Kosovo’s archives. These publications, often printed in very small numbers, circulate within closely-bounded ethnic communities and are read in the context of the histories, cultural ambitions and historical grievances of those communities. The Post-Archive, which will eventually become an internet site, places these publications in a single virtual site, allowing them to sponsor new sorts of memory work.

Andrew Herscher, ‘Warchitecture / Post-Warchitecture’, Volume 11: Cities Unbuilt, pp 68-77.