The Trouble with Provenance

Everything comes from somewhere. It’s a fact so self-evident it hardly feels worth saying. But beyond this obvious truth, provenance is a powerful industry. As a capitalist tactic, it addresses the problem of anonymous mass-production through the added-value of meaning. And it is everywhere. As such, our daily routines have fundamentally changed. No longer a simple succession of actions, they are now a complex sequence of meaningful objects, objects that reveal stories reflecting our moral and personal character. In the shower we lather with locally produced handcrafted soap. Our coffee packaging reassures us that the Ethiopian crop worker – his name is Abraham – earns a living wage. The mug we drink from, as told by the sales clerk, is a Scandinavian classic. We slice into a tomato, knowing that at the farmer’s market we shook the farmer’s hand. These things make us feel good; they reaffirm our egos, assuage our guilt, and remind us that we are interested and interesting individuals. It is 8:30 in the morning.

Provenance isn’t the backstory anymore, but the story. It has come to the fore, while objects recede into the background. A designer can no longer design a chair without a team of experts ready to craft its message and another team to convey it. Provenance has become the starting point of the design process; the search for the story is now the real design. Design, in the traditional sense, is thus positioned as a secondary act, the fashioning of the look of something so that it confirms the story. A humanitarian water bottle must look as if it came from a humanitarian project. A piece of starchitecture must look as if it came from the hand of a starchitect. A retro barbershop must look retro.

When provenance is combined with humanitarian efforts it is easy to become cynical. For years, the Turquoise Mountain project worked to rebuild a traditional neighborhood in Kabul and provide special artisanal skills training to its inhabitants. Now Turquoise Mountain rugs are on sale at Milan Design Week for prohibitive prices. Was this the ultimate goal? Or alternatively, when a tsunami hit the village of Ishinomaki, a workshop was set-up to create simple but beautiful street furniture. Hermann Miller leant a hand, and now the Ishinomaki brand fetches top design prices in boutiques around the world. Did the gods summon up a tsunami so that these designs could exist? Of course not. But in a world where everything relies on a sellable provenance, cynicism is the inevitable conclusion. And the provenance industry is forced evermore to prove its authenticity.

Distinguishing between meaningful and trivial provenance is the new consumer burden. Provenance has an authenticity problem that only worsens with its growth. In one sense, a lot of good has come from talking about provenance. More information exists today than ever before to help us make informed considered choices about how we live and what we buy. But more information exists, good and bad. As the provenance industry sharpens its means of communication and expands its presence it becomes virtually impossible to distinguish between truly meaningful facts, disingenuous half-truths, and meaningless trivia.

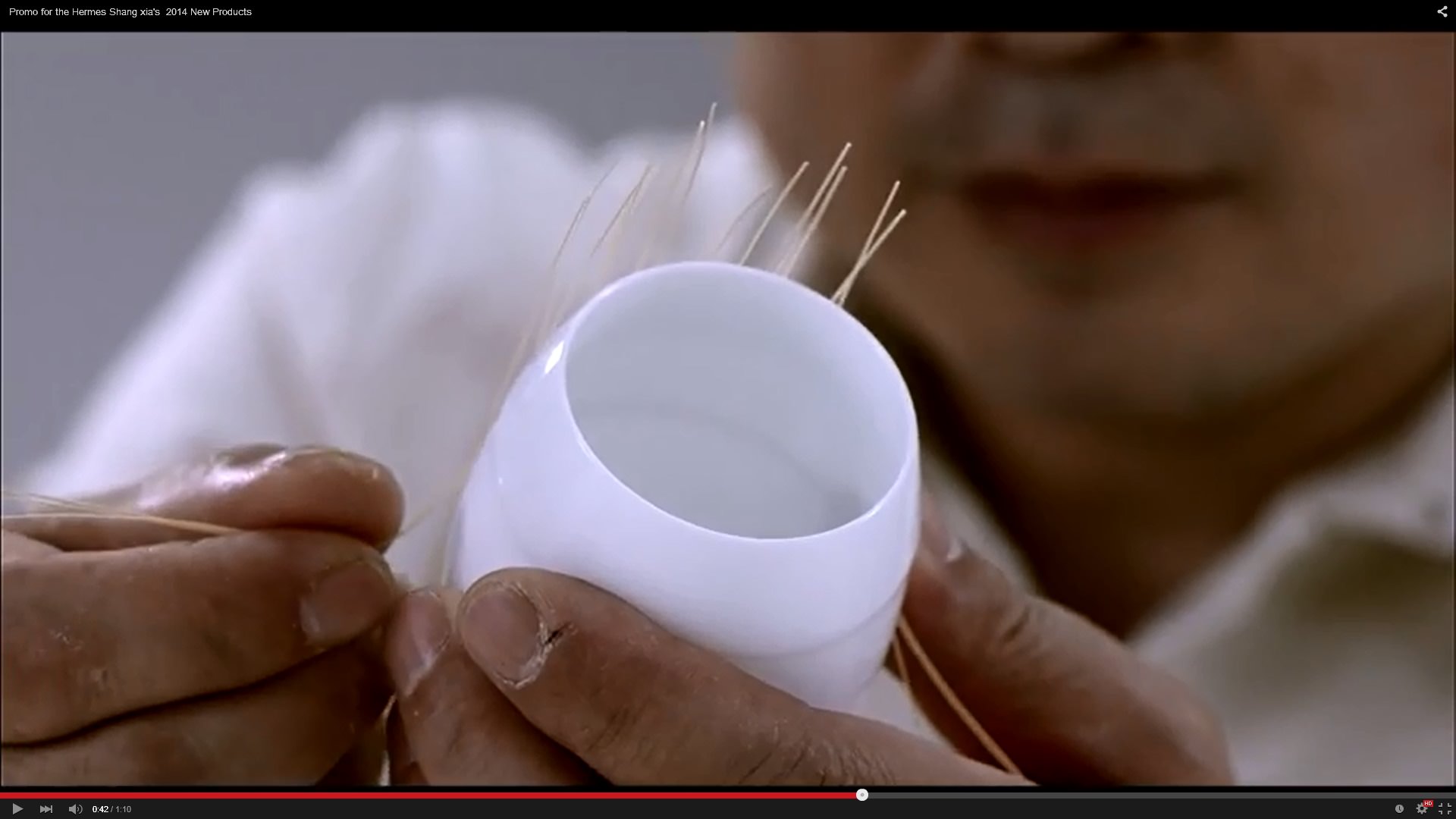

If provenance is the message, then video is the medium. An object rarely reveals provenance on its own accord. It needs others to do the heavy-lifting. Retail is a good place to start. Walk into Shang Xia, an upscale design boutique in Shanghai, and you will quickly see how an environment becomes a machine for conveying provenance. First, the interior design sets the ambience. In this case, it’s a womb-like space with walls of tri-axially folded white fabric designed by Kengo Kuma. It creates a calming antidote to the bustle of the street outside. But spatial design can only do so much. To tell the story behind the products, you will be ushered around to a series of video screens, which show in obscene detail the material technique by which each object is crafted. In one video bamboo is carefully shaved into fibers, and then those fibers are hand-woven to form a band that wraps around a delicate porcelain teacup. In another video, yak fur is meticulously hand-rolled into cashmere felt and pressed into sculpted seamless garments. Everything is shot in close-up, with a shallow depth of field focused on calloused knowing hands while rays of sunlight dapple in the slightly dusty air of a cozy workshop. Playing over this is the lamenting sounds of an erhu, a reminder that this is all part of some deeply historical trajectory.

Scour the websites of manufacturers today, and each will feature a litany high-production value videos telling you the stories behind the products, interviews with the makers, narratives about grand aspirations and humble beginnings, and ‘making-of’ sequences which prove the ultimate quality of what is on offer. Of course graphic design, interior design, architecture and product design all play their part in conveying provenance. But the sensory capacity of video, its ability to stimulate both sound and sight, and to tell a story in the most efficient way, insure it as the most important medium of the provenance industry today. As we move deeper into a digital world of online shopping and embedded auto-streamed content, provenance-related video will increasingly form a wall of everyday white noise battling for our attention.

Word-of-mouth is the other indispensable tool of the provenance industry. It’s not enough that the industry conveys to you an object’s provenance. They count on you conveying it to everybody else. When you buy into provenance, you also purchase the right to talk about it. For every person who quietly buys an Ishinomaki stool for the sheer pleasure of the object, there is another who recounts its feel-good story at their cocktail party, blogs about its phoenix-from-ashes roots, and tweets about its innate Japanese sensibility. The stool, once purchased, can’t just be a stool. It’s a story that needs to be told and retold.

Museums too are in the provenance business, telling and retelling stories about the objects they contain. Showing original works from masters has long been the museum’s main point of attraction and with fine art provenance is a relatively straightforward affair. But a curious problem is encountered at a design museum, where classic objects are mass-produced and owned by many. It feels somehow not enough to simply show a Sony Walkman, of which hundreds of thousands were made. Its presence is too everyday, too familiar.

As a result, curators employ a host of strategies to elevate its provenance. The first is to build a narrative that adds depth and meaning to the object. Sound clips, video, and exhibition design all attempt to lend significance to an object through elaborations on history, context, and attitude. In this respect, for better or worse, the museum moves closer to the tactics of retail design.

Another strategy is to find a version of an object with particular significance. For instance, at the Victoria & Albert Museum there is an Arne Jacobsen chair, a design classic that can be found in tasteful canteens and cafés around the world. But the chair that the V&A owns has a special provenance: it was sat on by Christine Keeler in a famous photograph shot around the time of her infamous Profumo affair. The photograph shows a nude Keeler seductively straddling a turned-around Jacobsen chair. In the gallery, the photograph is hung above the display chair, which is also turned around to suggest the connection between the two. As far as provenance goes, it certainly elevates the chair to something more than its more anonymous brothers and sisters. We can indulge in imagining the model sitting in front of us, her legs draped around the chair’s edge. But does this bring us any closer to the essence of the chair? Does this tell us anything about design?

A third strategy is to move away from collecting mass-produced objects to focus on limited editions and one-offs. Critical design, such as that practiced by Dunne & Raby has been of particular interest to museums as it makes incisive commentary on design culture, but also exists as a singular object which can be exclusively owned; the merging of design ideas with the exclusivity of the art object.

Certain designers have played to this system, catering to both museums and art collectors by producing highly crafted limited edition pieces. Nothing typifies this more than Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge chair, which recently sold at auction for 2.4 million pounds. Designed in 1986 and built by Newson himself through the painstaking hammering together of sheet metal over a fiberglass frame, today it has luckily found itself at the epicenter of a provenance bonanza, which pays top dollar for stories such as that.

But there is a subtle and slow-acting danger in solely seeking out pieces like these. It betrays a sense of reality. The museum’s mandate to collect and document the contemporary world suffers, as it substitutes a history of the everyday with a history of the exceptional.

Quite surprisingly, the V&A also offers some relief from this conundrum in one of the museum’s oldest galleries, the Cast Courts. And it’s here that we might find some instruction for how to escape the provenance industry’s more vexatious tendencies. The Cast Courts were created at the end of the nineteenth century, made up of plaster cast copies of some of Europe’s greatest sculptures and architectural details. Most defiantly, there is an entire copy of Trajan’s Column, cut in two so that it fits into the court’s still impressively high atrium space. Today it would seem outrageous to fill a museum with copies, however in 1873 when the courts opened there was perfectly sound logic to it. Since most people in Britain at that time could not afford a trip to Rome, why not bring copies back to London? These objects aren’t without provenance however. The tales of the men who travelled to far off places to create the casts would certainly make for interesting conversation. But little effort is spent in telling these stories here. You simply walk into the space and take in the copies as they are. Pure form divorced from their authors. There is something strangely liberating about this. Relaxing even. There is no inner voice saying: “look, you are seeing something important!” There is no pressure to somehow feel the genius of the maker through their work. You can assess the object in a rare naïve way. Your attention focuses elsewhere. To the dimension and proportion of David’s torso, to the script of Trajan’s column, or to the strange interplay between the objects accumulated in one space.

Knowing stories can be important and useful, but unknowing them can be equally productive. Can we radically unknow the provenance we’re told every day? Can we taste of cup of coffee for its flavor and not its branding? Can we assess the merits of a twentieth century design before we’re told its story? Would we begin to evaluate things differently without the incessant noise of a provenance industry constantly working the message? To end where I began, everything comes from somewhere. Provenance is an inescapable fact. But learning to occasionally and strategically turn down the volume could liberate us from a lot of the nonsense and bring us closer to some truth. Or at least some quiet.

This article was published in Volume #44, ‘On Display’.

This article was published in Volume #44, ‘On Display’.