The Project of Display

Fabrizio Gallanti talks with Hans Ulrich Obrist for Volume #44.

FG: Dear Hans Ulrich, I would like to initiate our conversation by considering some of your more recent projects and publications. You recently published a wonderful curatorial autobiography, where in a very generous way you reveal your education, how you entered in the art world, and your references. In particular, I am intrigued by the way how you inscribe your trajectory within a wider historical reading about the role of the curator within the arts. You have always been an amazing mirror for others to express themselves, through your conversations, while in the book you expose yourself with an exemplary clarity about the intellectual position you occupy. I also think that we could use this book as a springboard for our dialogue together with the curatorship of the Swiss Pavilion for the 2014 Architecture Biennale in Venice, where you reflected on the modality of presenting material, gathering numerous authors such as Tino Sehgal, Herzog and de Meuron, Atelier Bow-Wow, Philippe Parreno, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and many more. Where are you now with your reflection on the way to display content and to engage audiences? When I read your book I really had this amazing sensation that you are in a very long durational process of constantly rethinking the practices of dialogue with the public. Where will it go next?

HUO: In general, as curators we should also consider history and think about a history of display because obviously it is very often transient, ephemeral; it has, as Cedric Price used to say, an expiry date. It is a paradox that even within practices of architecture and visual arts where one can identify radical innovation, the question of display seems overlooked. If we look at the architect’s coffee table book, they usually cover everything from designing hospitals to luxury condominiums and schools; any architectural form. They might include interior design projects and even design for pottery or cutlery. In these massive volumes what usually is missing is the very often significant invention of display features that architects develop through exhibitions. If you consider this issue, there seems to be two parallel histories related to how architecture has to deal with limited life spans. On the one hand, the pavilion offers a great condition for permanent invention. This is a format that is rooted in notorious examples from the 20th century such as the Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe down to today’s young architects as SelgasCano or Sou Fujimoto and Smiljan Radić, who in the past years were invited by Julia Peyton-Jones and I to design the summer pavilions for the Serpentine Gallery in London. Pavilions are better known because they often become iconic and sometimes spectacular. On the other hand the projects for exhibition displays, which in some cases have been very important ground for the research of architects, seem to be victims of an impressive form of collective amnesia.

There is of course an amazing history of display features in the arts that can be traced back to the interior decoration of the Louvre in the 18th century that marks the beginning of the idea of the museum, which up until that moment there was only a standardized practice of display of the artworks in the academies. Since the French revolution, museums start to manifest a sort of mainstream style where you walk from room to room. The museum is a site that creates the national identity through its art collection: you induce the visitor to explore the nation through a carefully orchestrated journey. Then in the 20th century there was a major shift in the spatial and conceptual configuration of museums. It is crucial to mention Brian O’Doherty because of his fundamental essays on the idea of the ‘white cube’. He is one of the great geniuses of our time, who besides his activity as an art critic, has conducted a multifaceted trajectory as artist, novelist and as a member of the National Endowment for the Arts, generating crucial programs of support of the arts. His essays from the 1970s published in Art Forum provided the most acute understanding of the cultural, ideological and political conditions of display. He analyzes how since the decorative arrangement of the Louvre and still through the nineteenth century paintings were actually hung in very densely packed constellations, from floor to ceiling with frames touching each other. The Mona Lisa was juxtaposed with dozens of other paintings. It is with Claude Monet that we have a shift of attention, from a vertical depth of representation to individual works that grow in size and command a new typology of space so that the spectator can start to no longer see the work in the proximity of other works.

Another relevant step is when William C. Seitz removed all frames from Monet paintings for an exhibition at MoMA in New York: so the gallery became the display device. Or, if you wish, the framing device. We can say that the visual cues of the space are used more and more and we ended up with the ‘white cube’. In the words of O’Doherty, we could really say that the whole history of modernism is framed by the white cube. From that moment on the gallery itself became understood as potential field of intervention for the artist, who then started to innovate and invent display features within this expanded format. Richard Hamilton always mentioned Marcel Duchamp in our conversations as a key example, that he only remembered exhibitions that also invented a new display feature. For me, I think the same is true for architecture. I recall the Herzog & de Meuron show at the Centre Pompidou where all the material was presented on tables. I remember OMA ‘Content’ exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie by Mies van der Rohe in Berlin with the possibilities of actually seeing it from high above. I loved to literally go through the space and experience it from different heights. I remember ‘Les Immateriaux’ curated by Jean-François Lyotard at the Centre Pompidou in 1985 and being fascinated by the maze that was created to alter constantly the perception of the visitors. In general I think that the modes of exhibiting operate as corkscrews to drill your brain and activate your memory.

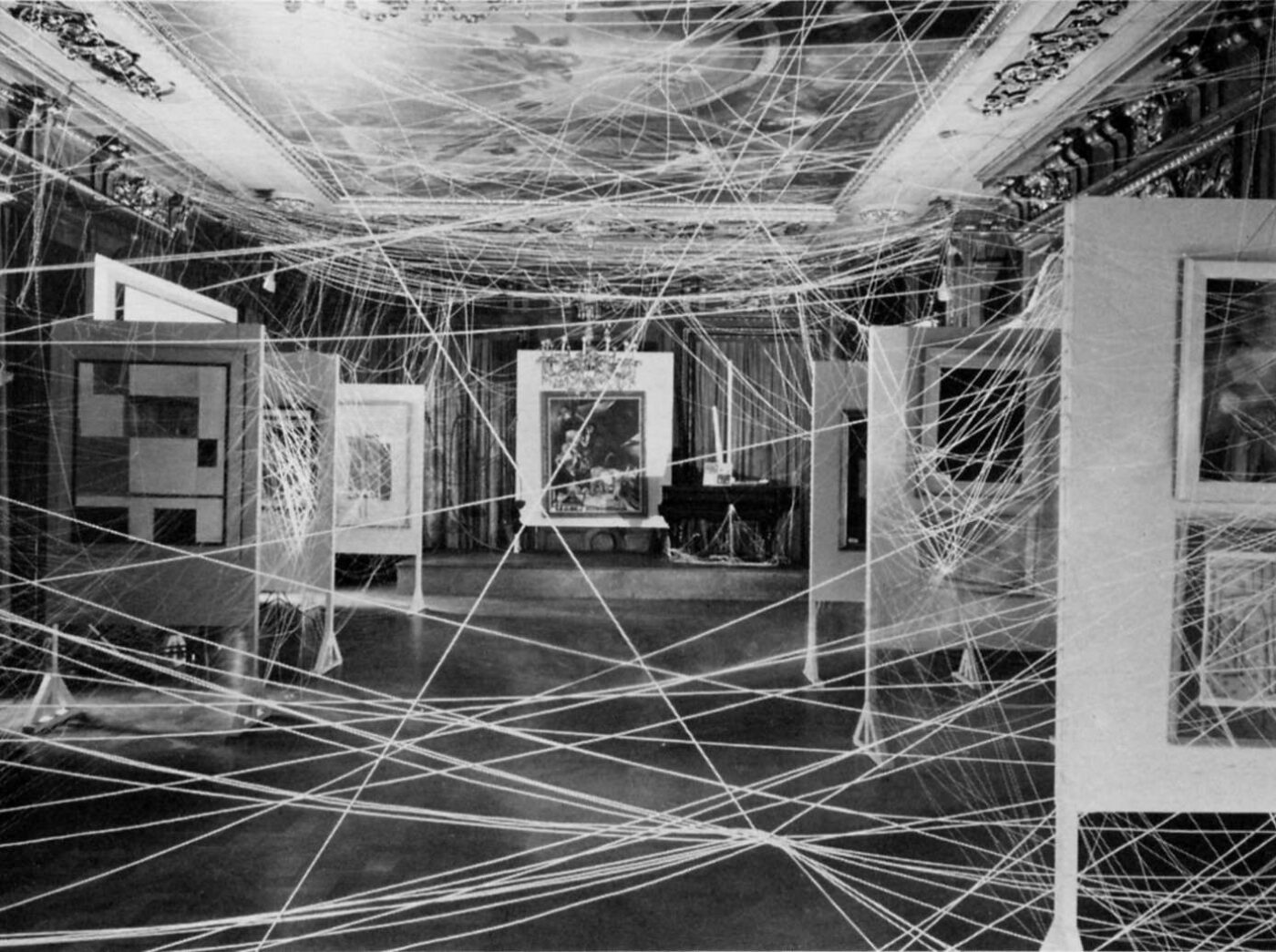

Coming back to the arts, two of these ‘corkscrews’ are from Marcel Duchamp. His surrealist exhibition in Paris in 1938 – with a room with hanging coal sacks creating a cavernous dark space – and then in 1942 the ‘First Papers of Surrealism’ exhibition in New York – where a mile of strings created a web, incorporating in the three dimensional lattice paintings and sculptures of other artists. The display occurred to make the experience memorable, in the word of numerous persons who saw the exhibitions. We can say that there is a robust historiography about artists exploring display techniques, while the same cannot be said for architects. It is revealing, for instance, that someone who had a crucial role in this, as important as Duchamp, Lily Reich, is not better known. One of the main regrets of Philip Johnson was not to have convinced Lily Reich to move to the USA, as he told me he believed that the history of American architecture and exhibition design would have been very different. Her relative obscurity is a proof of the amnesia that we experience about this issue even in the era of the internet.

Coming back to your initial question, when I assumed the role of curator for the Swiss Pavilion within the last Venice architecture Biennale, I started to wonder who would actually be the architects who were really significant for exhibitions during the 20th century. I came to the conclusion that it would be really fascinating to talk about Cedric Price and Lucius Burckhardt. In the forefront was the idea of an unrealized project of Cedric Price, the Fun Palace, which was originally imagined with the theater impresario Joan Littlewood and conceived to have a limited life span. For the Venice pavilion we wanted to mix the choreography of the 21st century with a more object-based display of the 20th century. Price already anticipated this idea in the 1960s because obviously, from the 19th century until that moment, the history of art was mostly the history of objects. But precisely in that period, arts historian such as Lucy Lippard started to understand the dematerialization of art, and we begin to see more time-based exhibitions and displays that foster a more communal experience outside the material limits. Price once said that the 21st century museum and display would utilize “calculated uncertainty “and “conscious incompleteness” – he was obviously aware of Heisenberg’s physics – to produce a catalyst for invigorating change.

In the exhibition that attitude was mirrored by the concept of ‘strollology’ by Lucius Burckhardt, a new science of actually going on a walk far beyond the limits of architecture, to the streets, in order to say that maybe the darkness of the night or the dirt in the neighborhood or the dust, the relationship between neighbors, could actually be as important than the built architecture. Environmental and social circumstances could outweigh the city’s visual environment, to quote what Burckhardt told me during one of the many walks we did together. It felt important to show together the archives of these two figures, and so I obviously had to address the conundrum of presenting archives. I tend to avoid models, as I think that they are not a pertinent way to experience and present architecture, and even more so architectural plans, which are like musical scores or computer programming, totally obscure to the non-expert. Hence, the rejection of the possibility of showing models and drawings led to this challenge of how we can show an architect’s archive differently. We had access to documents, photocopies, watercolors, sketches and videos, from the Canadian Centre of Architecture, where the largest part of Price’s archive is, but also we included material from Eleanor Bron, the partner of Cedric, and we worked with the Lucius Burckhardt library in Basel.

The goal was to create a dramaturgy to bring these dead materials alive. It was very important to build a team of artists and architects so I invited Herzog & de Meuron to conceptualize the exhibition, Atelier Bow-Wow to design a roof garden over the pavilion and who developed a Cedric Price kind of open birdcage where birds could fly out on the roof so visitors could go upstairs. I also invited the artists Tino Sehgal, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Philippe Parreno and Liam Gillick, the scholar Dorothea von Hantelmann and the producer Asad Raza to be part of a pluridisciplinary team. When we visited the library in Basel where the Lucius Burckhardt archive is with Herzog & de Meuron the librarians reeled out these trollies with original material in glass, and Jacques said, “it’s trollies”, because its this idea that they can be constantly moved and rearranged. So our strings as in Duchamp became the trollies, allowing us to develop a presentation of a dynamic archive. Tino Sehgal, who choreographed the exhibition, suggested to avoid tables and just have the trollies be wheeling out documents by students and young architects who would engage the audience in conversation. When you entered the pavilion in the morning it was completely empty and as the first visitor arrived a trolley was wheeled, and so on, so that when you have many visitors you have many trollies and students and the participants engaged conversations. Reproductions of the original material are constantly moved and rearranged as part of a conversation, mediating between the 20th century institution and 21st century future. A replica of the Fun Palace was put on wheels, as Cedric always wanted it to be. Lucius’s mental universes were suddenly floating in space, bringing us to launch a summer academy, managed by Lorenza Baroncelli and Stefano Boeri, so that during all of the Biennale every day there was another group appropriating the pavilion and converting it into their own mini-production. Every day we had a lecture by Dorothea von Hantelmann about the ritual of the exhibition. She basically wrote a book in public, a chapter every day. I think it is interesting to include art historians reflecting in vivo on the experience of the exhibition, as it happened with Molly Nesbit during the ‘Utopia Station’ exhibition at the 2003 Venice Biennale, which was co-curated by her, artist Rirkrit Tiravanija and I.

The very complex mechanism of the Swiss Pavilion was very much influenced by the ideas and thinking of the anthropologist Margaret Mead, who observed that if we look at exhibitions, visitors do not actually spend a lot of time in front of art works. I think that it was once measured that people in front of the Mona Lisa on average spend on average ten to fifteen seconds. Mead suggested that it is not only about appealing to the visual but to include touch, smell, to sound, so you weigh all the senses. Mead analyzed ancient ceremonies, such as barley rituals or a medieval mass, which appeal to all the senses. So we were very interested in this idea of the gesamtkunstwerk and how to develop a display feature involving all the senses. We included sound, Philippe Parreno developed the blinds so the space could suddenly go dark and allow film projections on the model of the Fun Palace or the walls of footage showing Cedric and Lucius. A more abstract notation was included in the signage developed by Liam Gillick, with the large black sign “Palazzo F” and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster with the neon “Lucius & Cedric”. The next step would be to introduce an olfactory dimension. There was also a very tactile component, because visitors could manipulate facsimiles of the original documents. The pavilion became an ever changing and dynamic environment, which was different every day and allowed for multiple surprises. I recently spoke with the artist Christopher Williams, who told me that he came with his students to Venice to do research and suddenly they realized that they could actually spend time in the Swiss Pavilion, so they just appropriated it and did their entire research in there.

FG: Thank you very much, this journey is fascinating, as it reveals two crucial issues. When you mention the sensorial component and the work of Margaret Mead, do you see that as a possibility to differentiate the space and the experience of a physical display from the digital and internet, where the predominance of the visual is obvious? On the other hand, connected to the book that you just published with Shumon Basar and Douglas Copland, The Age of Earthquakes, we are lead to believe that we live in an age where there is a multiplication of authorship, each one of us has a camera, everyone becomes an author. It really becomes the dream of Joseph Beuys where everyone is an artist. Yet, there still seems to not be a possibility to assume that idea within the exhibition format, where the authorship is associated with consecrated figures and professionals and the audience, which although more active does not yet produce content, which then enters the display itself. Do you see a potential in the medium term to imagine projects where the audience would be involved in a more active role as content creators?

HUO: This question leads us to the research that I am conducting with Simon Castets focused on the 89plus generation of artists – the first to have grown up with the internet – that will soon become an exhibition. Aware that the role of the digital is just beginning to be explored in the context of exhibitions, questions of display and interaction become fundamental. What we intend to achieve through our project is to understand how traditional notions of authorship and cultural heritage are changing. All these artists have an instant understanding and technological knowhow at their fingertips and rely on different social platforms to showcase new ideas and culturally iconoclastic approaches. This is why artist Ryan Trecartin said: “people born in the 90s are amazing; I can’t wait till they all start to make art”. As John Kenneth Galbraith said, “change comes not from men and women and their minds, but it comes from the change from one generation to the next.” If we believe in this assumption, as cultural producers, how can we track, document and present such change? But also, which are the implications besides the art world?

If we think of a certain irreverence towards traditional ideas of authorship in the arts, we can refer to the filmographic work of Adam Curtis. Within The Century of the Self, one of his most famous documentary series, the artists are somehow described as heroes of the individual self. The big question of the 21st century is instead how to foster collective action. In the age of the internet the potential to join, to come to shared engagement is there, and what would that mean in relation to display? That is what we would like to understand in the next years, hopefully, through the 89plus project.

But considering the role of the artist, I would like to go back to Margaret Mead. In an essay titled ‘Art and reality from the standpoint of cultural anthropology’ from 1943, she writes:“[I]n primitive societies, the artist is not a separate person, having no immediate close relationship to the economic processes and everyday experiences of his society.” The concept of the artist whose gift sets him apart, or who only becomes an artist because his life history has set him apart, is almost wholly lacking. The artist, instead, is the person who does best something that other people, many other people, do less well. His products, whether he be a choreographer or dancer, flutist or pot-maker, or carver of the temple gate, are seen as differing in degree but not in kind from the achievements of the less gifted among his fellow citizens. The concept of the artist as different in kind is fatal to the development of any adequate artistic form that will satisfy all of the sensibilities which are developed in individuals reared under the impact of these forms. Both of these differences, the difference between a ritual, which involves all of the senses and our present artistic practices which fractionate the sensuous man, and the difference between an artist, who is merely the best of a host of fellow practitioners and the artist who is different in kind from men who are hardly his fellows at all, are not inherent in the nature of civilization as compared with the nature of primitive society. Our own Middle Ages as well as many great cultures of the past developed complete harmonious rituals that involved the experience of every sense and the concept of the artist and the related concept of fine arts are both special bad accidents of our own local European tradition.

It is interesting to understand how it might just be a European angle that limits our experience, and maybe the 21st century display will come from other cultures and go towards a holistic condition. The question of sensibility is connected with the physical experience. I think it is fundamental to read again Mead: “the eye, the ear, the smell of incense, the kinesthesia of genuflection, the kneeling or swaying to passing procession, to the cool touch of holy water on a forehead” and to understand how to have all the senses involved, for which there is a great desire in the digital age.

FG: I was intrigued when you mentioned the necessity to create a choreographed experience of the archive. The archive is not originally even thought to be displayed, but yet it seems that there is a tendency to think that the museum can become a place for almost everything to be offered to the public. So if the museum originally was the Louvre, meant to display works of art, now we have museums of every single topic and every single item becomes inscribed in this museification of the world. But the modes of interaction, whether it is a design museum, a science museum, a car museum, seem all to come from the arts, where we expect the audience to look at an anatomical sample or a dress as if it was a sculpture or a painting. How do you see this situation currently, and do you see in the collaboration between artists and architects the possibility to break that quite static condition?

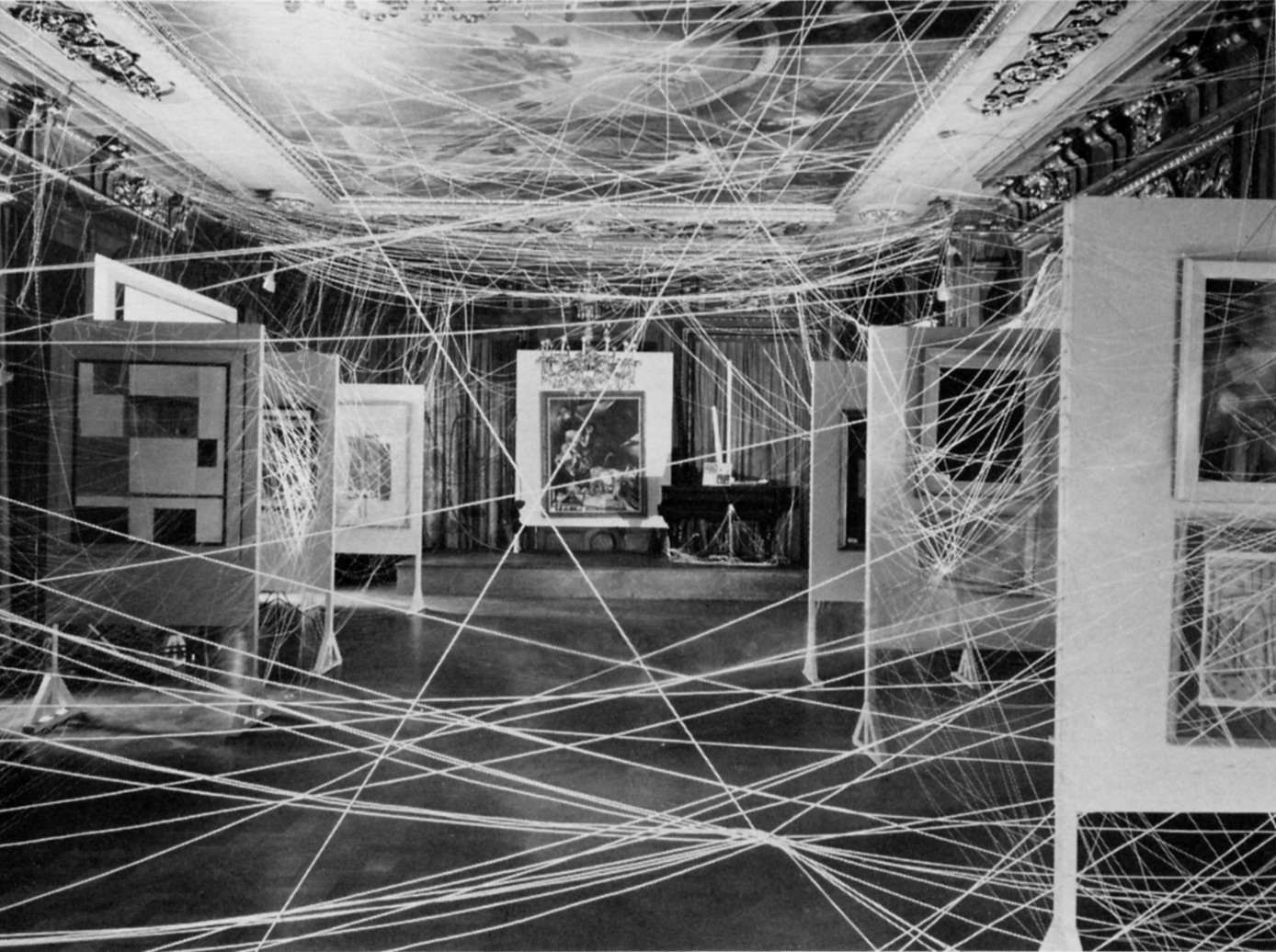

HUO: It is a fundamental dialogue. Penguin just released a book by me that contains a series of conversations, titled The Lives of the Artists, The Lives of the Architects, obviously inspired by Vasari, who basically showed how art and architecture in the Renaissance were together and not separated entities. I had a sort of Renaissance experience, in Frankfurt at the Stadelshule, while I was working with Kasper König on the book Public View, when Enric Miralles and Peter Cook were teaching there and introduced me to architecture, to Cedric Price for instance, who already in the 60s was thinking about cybernetics and the dissolution of architecture within cities and territories, anticipating, somehow, two key issues of today: the digital and the multiplication of centers. When I entered the art world in the 1980s as a student, the art world was still dominated by a few western art centers. This completely changed after 1989, when we started to see the emergence of a polyphony of centers. It also became important to include a non-western perspective on non-western art. This was one of the intentions at the base of the project Cities on the Move, which I curated with Hou Hanru. Curating has a lot do with listening, and we quickly understood by talking to artists and architects that the city was the element that connected them all because of the nomadization of culture and the value that we attribute more to ephemeral forms of art such as performance, installation, dance, concert, or film. As Etel Adnan said, one of the consequences of that nomadization is the loss of supremacy of the old and absolute centers of power and knowledge, and their relativization caused by the mushrooming of a multitudes of centers of interest in our fields all over the planet. With Cities on the Move we suggested that the arts are no longer national, that influence is instead generated by the contamination between people and ideas, which is very different than the national paradigm at the base of the 19th century museum. Art will not necessarily become homogenous – on the contrary, the artist is immersed, like radar, in the energies that circulate around the globe. As Édouard Glissant shows us this leads to an archipelago. It is not a continental logic. That means for display we are not in the logic of a continental display that homogenizes but in a more sheltering and welcoming archipelago.

The first time I experienced this archipelago condition was with Mario Merz’s La Citta Irreale show in Zurich in the 80s, where he created a city made out of igloos and each igloo was its own zone which were then connected by tentacles. This inspired us for Cities on the Move to have these temporary autonomous zones and self organized zones, which Rem Koolhaas and Ole Scheeren interpreted for the version of the show at the Hayward Gallery in London. This reading of globalization, as a multiplicity of centers, is one of the great stories when we will look back at what happened at the late 20th early 21st century. Every morning I read 15 minutes of Édouard Glissant. How we can actually negotiate and engage with a global dialogue without succumbing to the annihilating forces of homogenizing, resisting these homogenizing forces and produce difference?

FG: It is interesting that you return to 1989: giving such preeminence to that historical turning point implies that aesthetic practices have a deep connection with political, social and economic conditions.

HUO: 1989 is a fundamental moment: the fall of the Berlin wall, the exit of the Soviet Red Army from Afghanistan after almost ten years of military occupation and the students’ insurrection in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. That succession of events caused the beginning of a post-Cold War period. But it is also the year when Tim Berners-Lee, a British scientist at CERN, wrote the coding and protocols of the World Wide Web, establishing the basis for the digital culture of today. 1989 is a milestone that generated multiple transformations, deeply affecting art and architecture. Some of these are yet to be fully developed, for instance, if we return to consider the issue of display, the potential of the digital is still to be understood. MoMA design curator Paola Antonelli has been exploring the intersections between the internet, digital research and design production, expanding the boundaries of the museum collection. But a lot more needs to be done. I think it will be crucial to follow the developments of the artistic and intellectual production of artists and authors who grew up within digital culture, the members of what Douglas Coupland calls the “Diamond Generation”.

At the end of the 80s we shifted from ‘continental’ and homogenized systems of display to the archipelago condition. We are now in a moment, when, most likely, we will move from that condition to something new that we probably don’t imagine yet. 89plus tries to accompany and capture the emergence of new paradigms around display. Curating always follows art, so it is an exciting moment to be close to a new generation that oscillates between the analog and the digital.

FG: What you are implying is that the irruption of the digital will probably open a new phase, somehow ‘post-archipelago’, of which we are yet to see the formats and contents?

HUO: Yes, I think the internet has caused a crisis of representation, dislocating the experience and curatorship from the sacred space of the gallery or the museum but moreover altering the relationships of time and space. We can fairly assume that more art is accessed now through the web than by visiting museums, a tendency to which institutions have responded becoming nodes in digital networks.

The success of the internet has also consequences: one of the patterns that we have observed through the 89plus research is the concept of the ‘filter bubble’. This condition was underlined, for instance, in the work of young film-makers and artists using moving images such as Sarah Abu Abdallah, Darja Bajagić, Simon Lässig or Valia Fetisov, who were screened at the Centre Pompidou within the ‘#89plus Prospectif Cinéma’ program. A filter bubble is the mechanism by which automatic algorithms select online content that a user might want to see based on data provided by the same user, such as location, search history, personal data. It avoids exposing users to any information that might be in disagreement with their viewpoints, de facto isolating them within a coherent ideological environment, what Eli Pariser, who coined this concept, calls a personal ecosystem. For Pariser, the power of these mechanisms goes against the original nature of the web that was supposed to stimulate openness, generating instead closed systems of knowledge, harmful to society and to individuals.

So, if at the end of the 80swe had to resist homogenizing forces of globalization via the multiplication of centers, today it would be very interesting to understand how to counteract the mechanisms that support the ‘filter bubble’. The artists who we are following within 89plus are developing strategies and positions to question and challenge such expanding forces.

FG: So, are you trying to understand how to burst the bubble?

HUO: Yes, and we still do not know how this will happen. Perhaps this conversation could be considered a waypoint marker, from which we can chart the progress of these artists’ work and developments surrounding the question of a post-archipelago display.

This article was published in Volume #44, ‘On Display’.

This article was published in Volume #44, ‘On Display’.