The Counter-Map and the Territory

Official maps are instruments of power, benefitting some while impoverishing others. Inscribed in the law, they fortify the territorial interests of a select few. This is especially apparent in places where the pressures of resource extraction collide with land claims by disenfranchised indigenous groups. In Papua, where capital-rich mining and logging operations rule, local groups are attempting to stem the tide of environmental destruction by creating their own maps; counter-maps that demonstrate ancestral domain. The third week of The Writings on the Wall opens with Nabil Ahmed exploring how to fight a map with a map.

Shaped like the neck of a giant bird, Papua is one of Indonesia’s largest and most profitable provinces yet its poorest. Far from Indonesia’s capital Jakarta and the seat of power, it makes up half of the world’s second largest island New Guinea. While remaining geopolitically peripheral, Papua and West Papua have powerful global connections. Among its vast natural resources, in the Mimika region lies the planet’s largest gold and copper reserves. The land is covered in tropical, coastal mangrove forests and glacial mountains; the island is considered to host the most bio-diverse and largest forest in the world after the Congo and the Amazon. At the same time the territory remains under brutal military occupation by the Indonesian State. US mining corporation Freeport McMoran, a major environmental polluter that operates the Grasberg mine in Mimika has shadowy links to Indonesia’s military, responsible for documented massacres and human rights violations against the Papuan people including aerial bombings, extrajudicial killings, torture, assassinations, disappearance, detention, and rape of civilians. Papuan land is under threat from large-scale logging, mining and deforestation. Two worlds of violence, political and environmental, collude: the punitive power of both the Indonesian state and global ‘extractivist’1 capital against peoples still searching for an independent state. In light of current indigenous and environmental activist gains in the Indonesian constitution – which recognizes customary forest rights and practices such as participatory mapping – tactics for evidencing environmental violence in West Papua might help push the region towards its emancipatory dreams.

Hole in the earth

Freeport PT Indonesia, a subsidiary of Freeport McMoran began a large-scale mining project in West Papua with support from President Sukarno’s regime as early as 1963 while Papuan territory was still under dispute with the Dutch. Allowing the mining company to seize this remote part of what was soon to be Indonesia’s unquestioned territory was part and parcel of President Suharto’s doctrine of ‘New Order’, which used development in the form of foreign investment as one of its main economic drivers. Handed over several years before the so-called ‘Act of Free Choice’ of 1969 the Freeport Grasberg mine came to both symbolize and act as a site of conflict for the annexation of indigenous territories. While it is Indonesia’s single largest taxpayer, the company is unaccountable for its decades long environmentally destructive practice of open pit mining.

A history of destruction can be traced back to a series of political scandals and what Papuans consider an act of betrayal by the international community. West Papua came into its political existence as a swansong of Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia and during the height of the Cold War. The militantly anti-colonial President Sukarno used the iconic 1955 Bandung conference that signaled the birth of the non-alignment movement to solicit international support for its claim to the western half of New Guinea then still under Dutch colonial rule. The Dutch were reluctant in giving up Papua while Sukarno insisted any land that the Dutch controlled in the archipelago would be part of Indonesia. When matters escalated the Kennedy administration intervened by brokering a deal known as the New York Agreement with both governments in 1962, which placed the disputed territory under temporary UN protection. The driving motivation behind US involvement was to find an anti-communist ally in Indonesia against an already disastrous war situation in neighboring Indochina. Both parties agreed that the Papuan people would be given the choice to decide whether to join Indonesia or create their own state. In reality the 1969 Act of Free Choice was a calculated plot that saw a militarized Indonesian state under the genocidal Suharto regime orchestrate the voting to its advantage, practically at gunpoint. An anti-colonial nationalist project thus categorically denied the indigenous people of West Papua their right to self-determination.

The Free Papua Movement (OPM, Organisasi Papua Merdeka) and other groups have fought a guerilla war against the state immediately following the Act of Free Choice, while a host of indigenous activist groups and politicians have continued to negotiate and infiltrate the state.2 There are no accurate figures but hundreds of thousands of Papuans have died in the conflict or have been displaced. While there is rich diversity in language, culture and customs the Papuans have forged a strong national identity against the occupation symbolized by their flag, the Morning Star. The raising of the flag remains illegal under Indonesian law and Papuans have faced violent reprisal from the state. Papuans are faced with the complex and difficult political task of sustaining an independence movement against powerful state and global actors. In many ways the Grasberg mine and its environmental violence has been a nexus of their grievances and a site of conflict as early as 1977 when the Free Papua Movement blew up an ore pipeline at the mine. The military retaliated with Operation Tumpas (annihilation) killing thousands of civilians.3

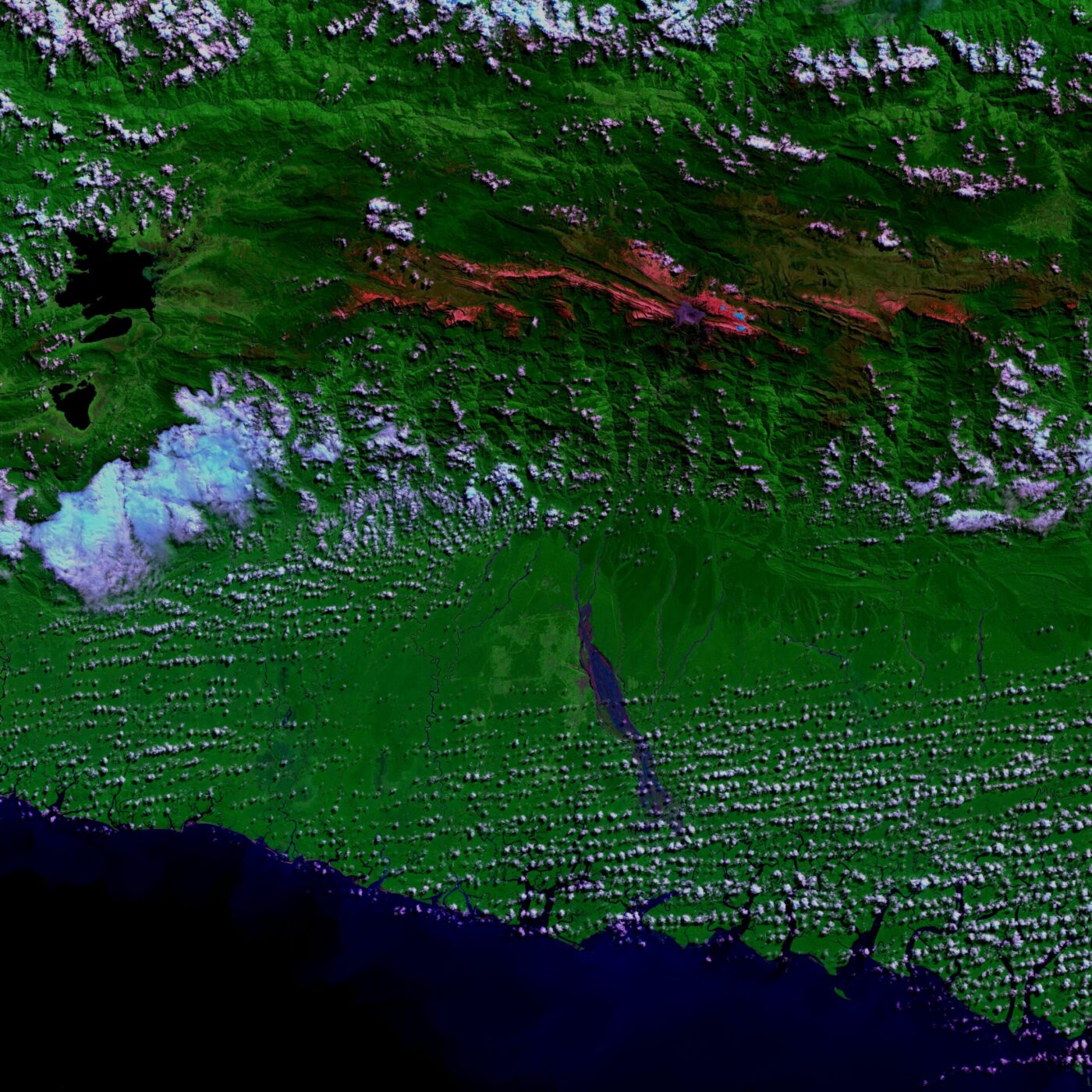

In the Mimika region mining and its tailing has permanently altered the landscape. Freeport, which now shares the mine with Rio Tinto uses a 293,000-hectare area including the Otomina and Ajkwa River to the Ararfura Sea in effect as a geotechnical system for tailing deposition. The journey for the toxic waste begins from the mine located over 4,000 feet above sea level through its ore-processing centre down to the lowland estuaries and a diverse forested coastal zone of mangroves, sago, tropical, and cloud forests. The movement thus traverses both a vertical and horizontal path of destruction. Over 200,000 tons of tailings flow through the river per day into this area, which contain highly toxic arsenic, copper, cadmium, and selenium. The mine is in the heart of the ancestral land of the indigenous Amungme and Kamoro, two of the many ethnically Melanasian indigenous people that make up Papua. Already large tracts of their ancestral forests have disappeared, with equally irreparable biodiversity loss. The environmental violence backed by military force has brought death and sickness, destroyed food sources and livelihoods of both the Amungme who live in the highlands and the Kamoro, who call the south coast lowlands their home. It can be argued the continued violence committed against these people amount to crimes against humanity.

It seems rivers are both the victims through pollution and instruments (geotechnical tailing management system) of a crime against nature and against peoples. The river is no longer only a river but a new form of assemblage, with the mine an out-of-the-way place that has severe local effects but at the same time plugs into the global political ecology of extractivist capital. Under Indonesian law the large-scale pollution caused by Freeport is illegal. In an interview Abetnego Tarigan, the Director of WALHI (Friends of the Earth, Indonesia), the country’s leading platform for the environment told me that his organization had won a case back in 2007 that found Freeport guilty of polluting rivers and destroying coastal forests. Yet no action was taken to hold the company responsible. Business remains as usual with plans to dig deeper into a spiraling hole in the earth.

Counter-mapping

Recent developments and activism in Indonesia might renew ways of evidencing environmental violence in West Papua. Wider indigenous and environmental activist movements might find ways of holding accountable those responsible for violence against the landscape, forests, and people in Papua. On May 16th, 2013 the word ‘state’ was removed in front of the word ‘forest’ in the Indonesian constitution. Known as Ruling No. 35, customary forests are now classified as titled forests. The landmark ruling was a result of the Indigenous People’s Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), the indigenous community of the Kenegerian of Kuntu and the indigenous community of the Kasepuhan of Cisitu petitioning a judicial review on numerous articles of the National Act No. 41 Year 1999 on Forestry. The 1999 law had already recognized customary forests however it had defined customary forests as “state forests located in the areas of custom-based communities.” 4 Finally, the possibility of territorial wrongs righted had appeared on the horizon for millions of indigenous people in the archipelago.

The exploitation of Indonesia’s land resources started under Dutch colonial occupation. Like other colonial projects that produced terrible violence around the planet, the Dutch extinguished the rights of the indigenous people of their own land through forest enclosures under the term ‘Domeinverklaring’ in 1870. As a form of territorial violence what had been part of the commons turned into state property. After gaining independence in 1949 Indonesia only further asserted its rights on indigenous land, completed with the annexation of Papua. What began full swing under President Suharto’s regime of crony capitalism and rampant corruption of exploiting forest resources has not stopped since he resigned in 1998. The Forest Law of 1999 mentioned earlier only saw an increase in conflicts; land grabs surrounding forests in indigenous territories estimated to be forty million hectares spread through the archipelago in Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulewasi, Maluku, Flores and Papua. Conflicts have mainly resulted from overlapping claims where state and local governments handed over concessions and permits to logging, mining, and palm oil companies.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, in 2010 Indonesia as a whole had 52 percent forest cover with an annual deforestation rate of 0.5 percent over the last decade.5 So far much of the deforestation and related conflicts has taken place in forested regions in Borneo and Sumatra. However vast tracts of Papuan forests are equally under threat. Coastal swamp and mangrove forests in the Mimika region are victims of pollution from the Grasberg mine. But under the new constitutional ruling what had been indiscriminately destroyed or considered expendable, as state-owned forest could perhaps now be questioned. Up until the ruling any local claims to territorial rights were always trumped by state power and government produced maps. In response the practice of counter-mapping has been a useful tool for indigenous activists for making local territorial claims.

In order to produce evidence of territorial rights, maps and mapping is a crucial technical-legal instrument. Since the passing of the Forest Act of 1967, the same year mining concessions were handed over to Freeport no government mapping exercise has taken into account local land claims. In response to the state’s strong territorial claims through mapping, many indigenous communities have come up with their own maps. The practice of counter-mapping by local indigenous communities has played an active role in Indonesia as early as the 1990s beginning in West Kalimantan.6 Computer maps are produced with geo-referenced field data gathered by local mapping teams, sketch mapping, and GPS that at the same time can identify ancient, generational territorial rights, and sacred land. Thus two very different epistemologies, science and indigenous knowledge are seen to be acting together often with the help of NGOs acting as facilitators.

Though in light of the recognition of customary forests, the need to produce counter-maps have become even more crucial in order to demarcate ‘state’ and ‘local’ forests in contested territories and evidence pollution and deforestation such as in the Mimika region in Papua. The two organizations, which have been spearheading the urgent counter-mapping project, are Network for Participatory Mapping (JKPP) a grassroots organization that uses local spatial knowledge to evidence land rights and the Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN). The two organizations together have submitted ancestral domain maps outlining over two million hectares of customary forests to the Indonesian Geospatial Information Agency. So far the two territories that have at least been partially mapped are West Kalimantan and Papua, which took as long as fifteen years to complete. Yet it remains to be seen how the government will incorporate this rich spatial data to implement the changes in practice. Here lies the challenges faced by indigenous activists: the longer it takes for the maps to be produced, the less chances there are of implementation in the law. Furthermore the customary rights to forests also have to be recognized separately by regional governments and not only at a federal level. According to Abetnego Tarigan from WALHI, official mapping data does not exist. There are still over thirty million hectares of indigenous territory left for mapping, a mammoth task for the activists, especially when the encroachment on land continues.

Within the context of evidencing deforestation caused by the activities of the Grasberg mine, counter-mapping can also be a valuable tool. Historically mapping as a hegemonic practice and more recently remote sensing have been extensively used to locate earth’s resources. The same methods are now increasingly used to evidence resource exploitation for the service of environmental and human rights. For instance, a research project is currently underway that brings a number of scales, corresponding field data, and forms of territorial evidencing to produce a composite picture for evidencing environmental violence in West Papua.7 The project takes shape around essentially three sets of spatial data. First it seeks to identify the location of Grasberg’s waste dumps and tailings. This includes understanding the geo-technics of the tailing management system. Second using existing forest mapping data it proposes and identifies demarcations of customary forests in the areas affected by the tailing area. Third multi-temporal satellite images of the region can show land cover change that has already taken place. Superimposing and calculating these three sets of data can show what customary lowland forest areas have been destroyed or might be under threat from future deforestation. Combined with fieldwork, and analysis to determine the chemical makeup of the tailing area can begin to connect this wealth of data that can be used and monitor the mining company’s activities. The lowland forests are part of the ancestral land of the Komoro people whose livelihood is severely threatened from the mining activities especially the massive tailing depositions. While at the same time the Indonesian military continue to use violence to maintain its occupation. Recently Benny Wenda, a Papuan indigenous leader in exile in the UK reiterated to me that this clearly constituted ‘genocide.’ A skilled diplomat, his activism is focused on raising the question of the West Papuan right to self-determination to forums such as the United Nations.

The anthropologist Nancy Lee Peluso has called forest mapping in Indonesia a form of ‘local territorialization’ where the maps and map-making act as an advocacy tool for land rights.8 Using the same language of state cartography such as zoning, resources, land use, and boundaries, indigenous people are asserting their own claims for securing land rights. The inclusion and recognition of ancestral domain maps in the Indonesian national spatial data infrastructure is a win for the indigenous people of the archipelago. Politically for the nation state it fits into the state motto Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity) with increasing recognition of indigenous rights. On the other hand for West Papua, inclusion can be seen to even detract from the independence movement and its long time dream of Papua Merdeka (Free Papua). Counter-maps are like counter narratives yet do they lose their power when included in grand narratives such as nationalism? Maps and imagery of landscape transformation in Papua can provide evidence towards realizing this emancipatory dream in legal and contemporary forums. The question that remains is how to win incremental rights while keeping alive dreams of emancipation.

Nabil Ahmed is a researcher and writer working at the intersection of spatial practice visual culture and environmental humanities. He completed a doctorate in Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he has a long-term research affiliation with Forensic Architecture.

The Writings on the Wall is an editorial project developed in collaboration by Volume and Beta – Timișoara Architecture Biennial, about the capacity of loopholes to create exceptional experiences among the laws that produce our urban spaces.

The term is derived from extractivism, meaning profit-driven mineral exploitation.

For a remarkable study of the complex and nuanced Papuan independence movement, and particularly how it moves through collaboration just as much or more than resistance see Eben Kirksey’s book Freedom in Entangled Worlds: West Papua and the Architecture of Global Power.

West Papua Media Alerts. “Chronology of events in West Papua.” Accessed October 10, 2013 at: www.rizeofthemorningstar.com

Indonesia Nature Film Society & HuMa. The Customary Forests after the Constitutional Court’s Ruling No. 35. Video documentary, 2013.

‘Papua and West Papua: REDD+ and the Threat to Indigenous Peoples. Rights, Forests and Climate Briefing Series.’ Forest Peoples Programme, October 2011.

Kalimantan rainforests in Borneo and numerous indigenous communities suffered devastating forest exploitation at the hands of multinational companies and the Indonesian state. The anthropologist Anna Tsing has written an insightful book on connecting the local forests to the global political ecology see: Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection.

The research project is part of Forensic Architecture, an ERC funded research project that explores the role of architecture and international law at the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London with Adam Bobbette (Scapegoat/University of Hong Kong) as collaborator.

Nancy Lee Peluso, ‘Territorializing Local Struggles for Resource Contol: A Look at Environmental Discourses and Politics in Indonesia.’ In Greenough, Paul R, and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing. Nature in the Global South: Environmental Projects in South and Southeast Asia. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003). p.231–252.