Swiss Air

Swiss Air

Christian Kerez interviewed by Jeffrey Inaba

Christian Kerez’s work is best known for the conceptual inventiveness he brings to ageold problems of form and tectonics. What is less known is the architect’s equally refreshing approach to mechanical systems. Here, Kerez talks about the Leutschenbach School in Zurich, and his ideas to integrate the air and other building services into this densely packed design.

Jeffrey Inaba: The Leutschenbach School is best known for its structural system – the beautifully designed external frame which enables the interior space to be column-free. But you are an architect that conceptualizes so many aspects of a building and the power of your work results from the densely woven threads of ideas that are nested in the form. So I wonder how other aspects were conceived. In particular, can you discuss the mechanical system: how was it treated as a design element? How did you think about it in relationship to the structure?

Christian Kerez: In the Leutschenbach School, a project that we finished in 2009, we created this reading of different spaces overlaid on top of each other which allowed us to challenge the assumed continuity of mechanical systems. On the ground level, you see the mechanical system as part of the elevator shaft, but there is a metal sheet covering the shaft which acts as a mirror reflecting the surrounding space. So even though the box is there, in a way, you don’t see it because it is reflecting other spaces. Then if you go upstairs, the mechanical systems are part of a zone where cleaning, sanitary and changing rooms are, so they all of a sudden disappear in a very narrow core-like area. And finally in the gymnastic hall on top of the building, the core is visible but it looks totally different than on the ground floor, because it’s much bigger. Because the gymnasium is just one space without any division, it’s quite nice to have this eccentric shaft, and it reads as a mechanical shaft and not a column because it’s off to the side of the room. The mechanical system is treated much differently on each level; we broke every expectation of continuity.

This was done to underline this spatial change from one level of the building to another. And the same goes for the sanitary system; the position changes in various plans and there are moments where it is preciously clad in stainless steel and then others where it disappears. The building is not naked but it’s not like some buildings of the 60s which had very clear functional goals. Rather, it is driven by a certain definition and understanding of space. The structure primarily defines the space and the mechanical systems are articulated and positioned to underscore this.

JI: The essential challenge for every architect is to achieve as much as possible within the given construction budget. This is an aspect of architecture that goes underappreciated. It requires a high degree of creativity because it necessitates inventing methods that are less than the cost of the conventional way of doing things. I was surprised to learn that the budget of the Leutschenbach School was relatively low, given the structure and materials used. Where were you able to economize? What decisions helped the building to be completed on that budget, and did those decisions involve the mechanical system?

CK: Yes, but I think it depends on how you compare the cost of the building. For instance, if you look at the cost per teaching unit or per student, it’s one of the cheapest schools built in Zurich in the last few years. However, if you look at the cost per cubic meter, it’s one of the most expensive schools. The reason the school is so cheap per student but so expensive per cubic meter is that it is compact. And actually the compactness was an architectural issue as opposed to an economic one, but in the end it had a great impact on the economics.

What I am always interested in as an architect is the challenge of placing various programs together. I am fascinated by the idea of creating new entities out of completely different programs. I also believe that placing these programs in such proximity gives more density to the meaning of the building. If you don’t separate everything, if you don’t say well here’s the school, here’s the gymnastic room, here is the mechanical shaft, here is the load bearing structure, you can create these wild things if you put them together. Other architects might say, this is one thing, that’s another, and between these different parts is harmony and peace. For me, if all the programs are placed in a single frame, they have to become one and can no longer be separated. And I think that the meaning that they can create together goes beyond the meaning that each of them can create on their own. So I would say that this idea of compactness interests me more than the pure economics. And compactness inherently integrates HVAC systems. This means that you can no longer look at what the HVAC engineer is doing as being separate from your role as an architect. And of course to integrate all these things together is not cheap; it’s extremely expensive and it demands a lot from the engineers and from the people working on the construction site. I honestly don’t know if I could build a school like this in any other part of the world because we have amazing handicrafts. But we could only afford it thanks to the fact that we were very economical with the amount of surface area: the surface area of the façade as well as the area of each floor plan. The floor plate is very, very small. But still if you visit, you will see that the space looks monumental. This is because there isn’t a functional separation between different parts. The circulation is the meeting room, it’s the room where people teach and where people walk – it’s just one space. Some visitors have even said it doesn’t look Swiss, it looks like a South American building because of this generosity.

JI: Your buildings are deceptively simple in appearance. There is always more than what first meets the eye in the sense that when looking more carefully at the project additional layers of design are revealed. Can you discuss the floor slabs? Are they shaped that way for purely structural reasons?

CK: There is vertical and horizontal ventilation and both kind of disappear but in different ways: the vertical connections by transforming the expression of the mechanical shafts on each floor, as I discussed, and the horizontal ventilation disappears into the folded ceiling. The structure and the mechanicals are one and you can’t tell where each one is because of this undulating ceiling; it is unclear whether the shape comes from the structure or a desire to conform to what is inside the ceiling.

Basically, there is a beam structure which creates the undulation, but each beam is not identical in terms of function. There is the sprinkler system, the ventilation, different parts of the HVAC system; it’s essentially an overlay of different functions which produces this monumental movement of the structure. In that sense, the mechanical systems and the structure are integral to one another; for instance, the position of the ventilation panel cannot be changed without having an impact on the structure. The geometry of the ceiling is a perfect match between the HVAC systems, as well as other technical requirements – like the acoustic insulation, the sprinkler system and ventilation – and the structure. The various elements become a part of this undulating shape which is governed by the load bearing of the structure.

JI: So does that mean that the mechanical and the sprinkler are all in the thin part of the slab? Or do they occupy the deeper part in some areas?

CK: The sprinkler is in the deeper part because the exit of the water always has to be in the lowest part of the ceiling, and the light is in the thinner part to allow the acoustic insulation to frame the light. The mechanical system is in the thicker part, but not in each beam.

JI: I know you’ve been working on the Villa Müller recently, where you seem to have taken a completely different approach to mechanical systems. Can you describe the project?

CK: Well, it’s different because all the vertical installations are visible from the outside and they are always framed by open columns so the shafts are not only open, but actually exposed to the exterior. So you can see people walking up and down the stairs, taking the elevator, and you can see even the tubes for ventilation from the outside of the building.

For me, this wasn’t so much a fascination with mechanical system as it was with creating an open space. This fascination was possible in the 60s but in our time it is hard to imagine, displaying mechanical systems is almost sentimental, because these systems are so familiar, they exist at a highly developed level in nearly all homes. Basically, we decided to place all aspects of the building which are shared elements – the elevator, the mechanical system, the columns – on the outside of the building to create a single slab with the largest possible sense of extension. So these elements become extensions that are no longer part of the main building – they are in effect treated as side buildings.

Because of that the positioning of elements is totally irregular. The building is a kind of bastard, you know. It’s totally un-pure. I like this impurity, and the ambiguity between structure, mechanical systems, and surfaces, and the denser meaning that they can create when they’re placed next to each other.

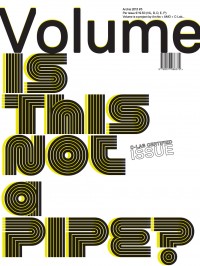

This interview is part of Volume #37, ‘Is This Not a Pipe?’.