School in Exile

Since the first appearance of Palestinian refugee camps after the Nakba, the Arabic term to indicates the exile of two-thirds of the Palestinian population in 1948, their architecture was conceived as a temporary solution. The first pictures of refugee camps showed small villages made of tents, ordered according to grids used for military encampments. As the years passed and no political solution was found for the plight of the displaced Palestinians, tents were substituted with shelters in an attempt to respond to the growing needs of the camp population without undermining the temporary condition of the camp, and therefore undermining their political right of return. However, with a growing population, the condition in the camps worsened. The precariousness and temporariness of the camp structure was not simply a technical problem, but also the material-symbolic embodiment of the principle that its inhabitants be allowed to return as soon as possible to their place of origin. Thus, the camp becomes a magnetic force in which political powers try to exercise their influence, and the refugee community vehemently opposes any attempt to normalize it. Every single banal act, from building a roof to opening a new street is read as a political statement on the right of return. Nothing in the camp can be considered without political implication.

Within this context, in June 2011, the UNRWA Infrastructure and Camp Improvement Program, directed by Sandi Hilal, decided to intervene in the conception and realization of a girl’s school in Shu’fat refugee camp. For the first time, a site specific and ad hoc design, not a pre-conceived and fixed architectural scheme, was produced.

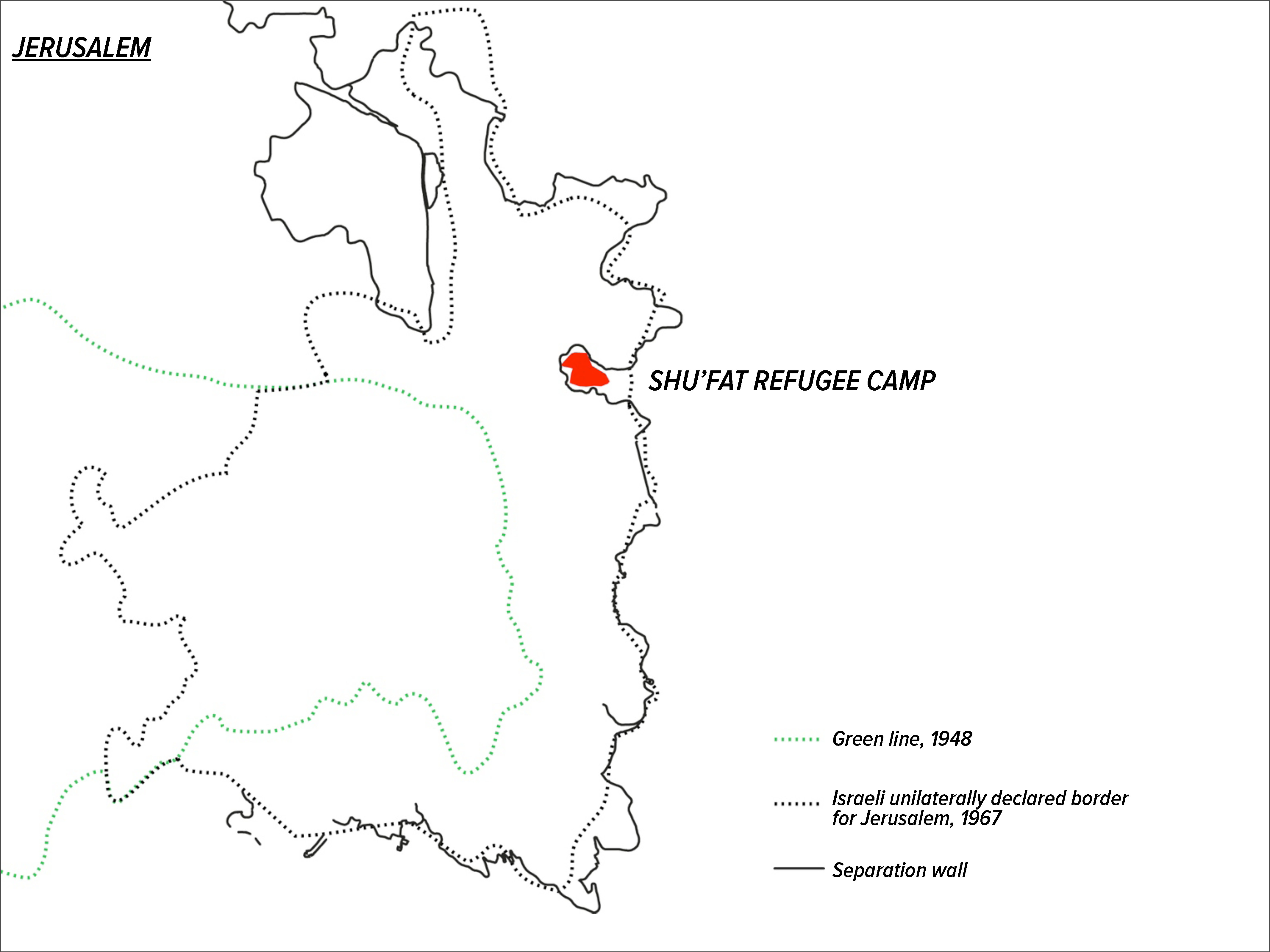

Shu’fat refugee camp was established in 1965 and is inhabited by 20,000 Palestinians refugees that were expelled from 55 villages in the Jerusalem, Lydd, Jaffa and Ramleh areas. The political context that surrounds the project is extremely deteriorated. The Shu’fat camp is almost entirely enclosed by walls and fences built by Israeli governments since 2002, trapped in a legal void, neither inside nor outside Jerusalem borders. The inhabitants of Shu’fat are threatened to be deprived of their Jerusalem residency documents and therefore once again be forced to leave their homes.

Is architectural intervention at all possible in such a distorted and unstable political environment? And how could intervention be possible without normalizing the exceptional and transitory condition of the camp? How could architecture exist in the here and now of the camp, yet remain in constant tension with a place of origin?

Architecture is too often seen in the Palestinian context as simply a technical and bureaucratic solution with no social and political value. Too often, architecture has been humiliated in vacuous formalism; to look green or sustainable or efficient, apolitical answers to political problems. Too often within the humanitarian industry, architecture has been reduced to answering to the so call “needs of the community”. Rarely has architecture been used for its power to give form to social and political problems and to challenge dominant narrations and assumptions.

The Shu’fat School embodies an ‘architecture in exile’: it is an attempt to inhabit and express the constant tension between the here and now and the possibility for a different future. The architecture of the school does not communicate temporariness through an impermanent material construction. These materials are too often instrumentalized for a “politically correct” architecture that relegates refugees to living in shantytowns. Rather, through its spatial and programmatic configuration this architecture in exile attempts to actively engage the new ‘urban environment’ created by almost seventy years of forced exile. Perhaps this is a fragment of a city yet to come.

The design of the Shu’fat School is inspired by the pedagogical approach cultivated by Sandi Hilal and myself (Alessandro Petti) in Campus in Camps, an experimental educational program based in Dheisheh refugee camp in Bethlehem, Palestine. (www.campusincamps.ps). Our approach is devoted to the formation of learning environments where knowledge and actions are the result of a critical dialogue among participants, and in direct connection with communities where the interventions are taking place. To describe this egalitarian and experimental environment, we use the Arabic term Al jame3ah. Translated to English as “the university”, the literal meaning of Al jame3ah is “a place for assembly”. As such, this educational approach is to create a gathering space and a pluralistic environment where participants can learn freely, honestly and enthusiastically, and where participants are involved in an active formation of knowledge based on their daily lived-experience.

Al jame3ah is a space that aims to contribute to the way schools and universities understand themselves, and overcome conventional structures. In doing so, it seeks forms of critical intervention for the democratization of knowledge production.

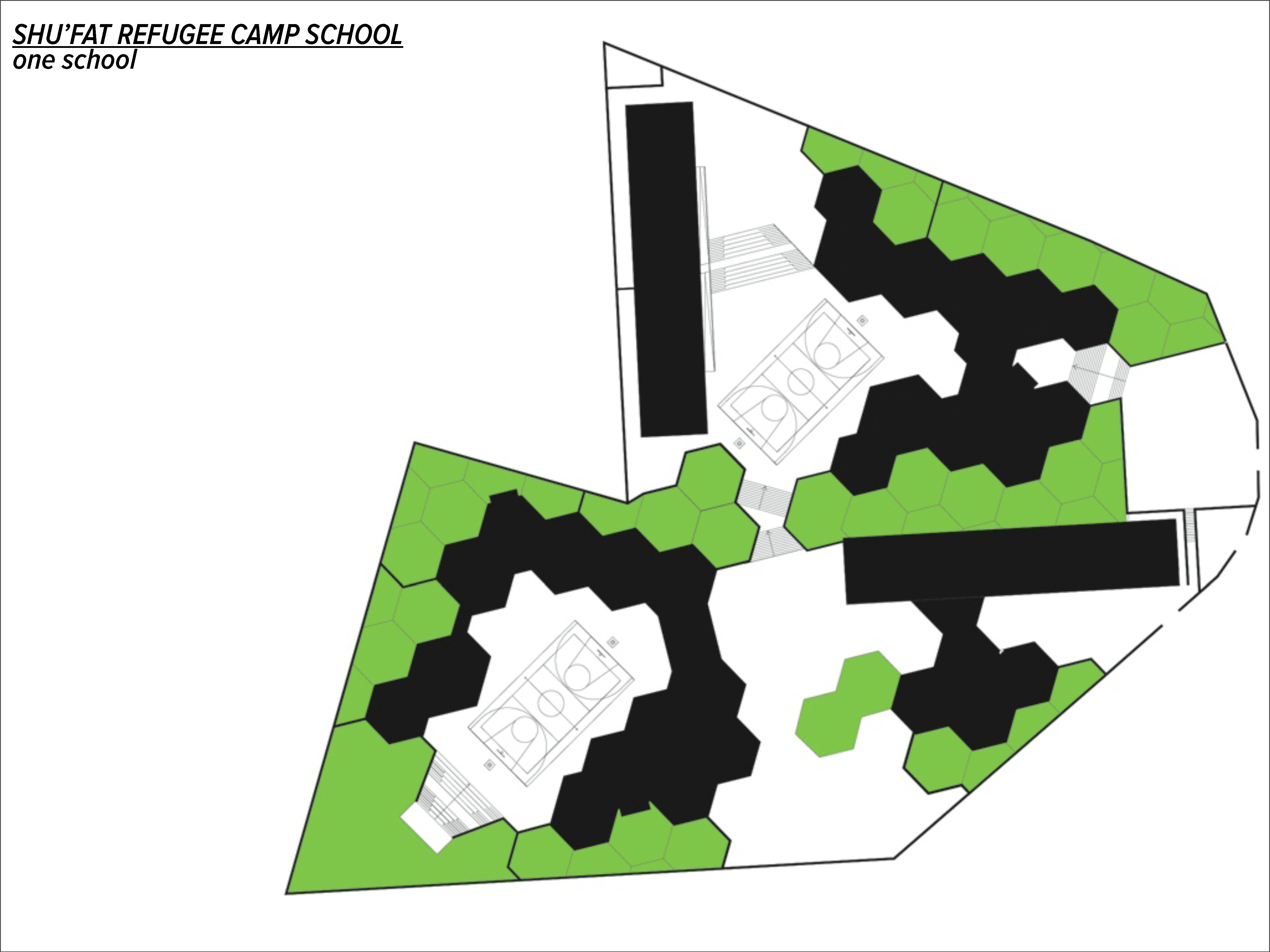

DAAR, an architectural office in Beit Sahour, Palestine, for this project comprised of Petti, Hilal and Livia Minoja, in collaboration with the engineer department of UNRWA and with the participations of students, teachers and organizations from the refugee camps, imagined the ‘school in exile’ as an occasion to elaborate a fragment of a different approach to education and society – a school to be experienced by the students not as a site of repression and discipline, but as a site of liberation and responsibility.

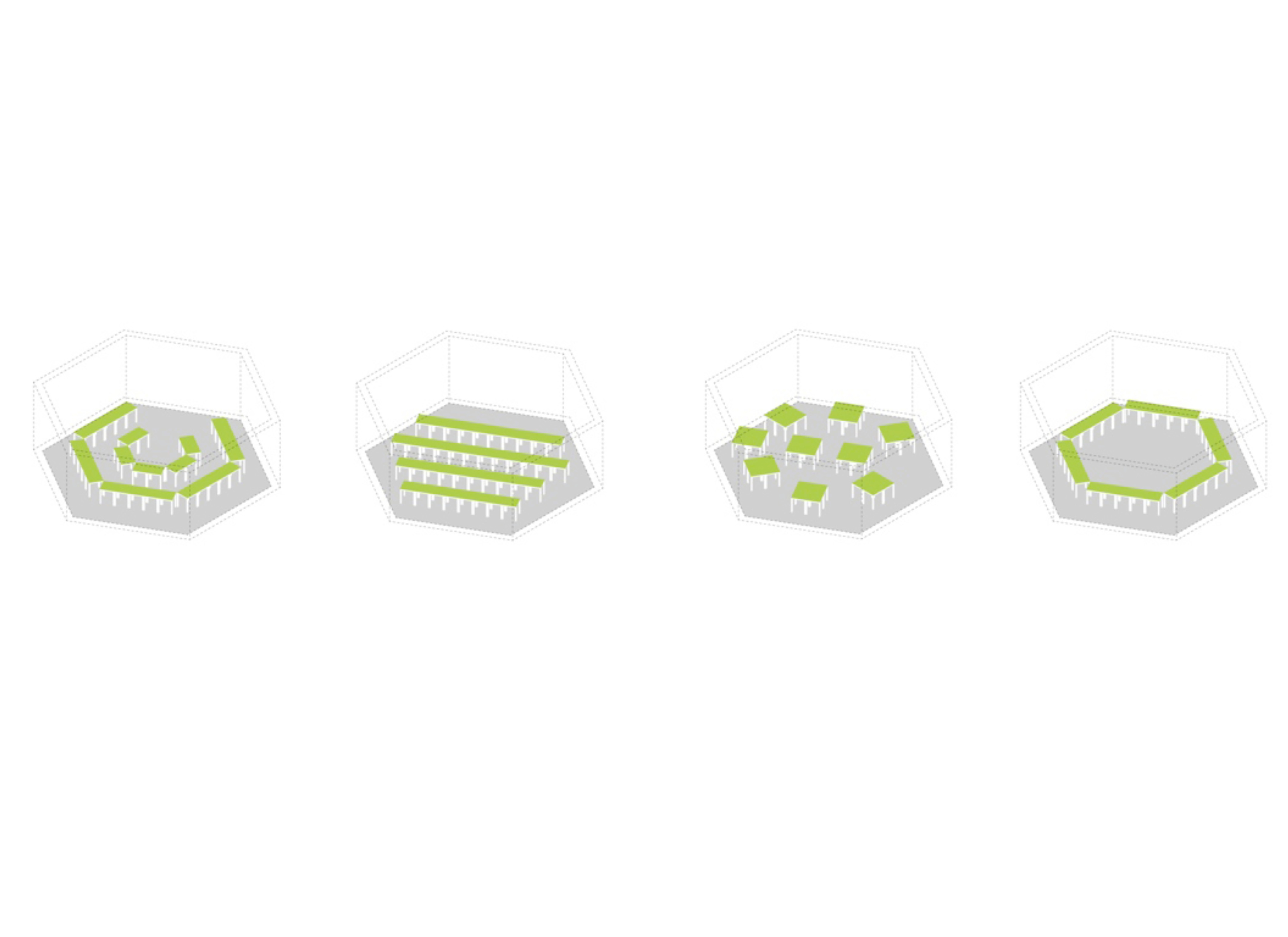

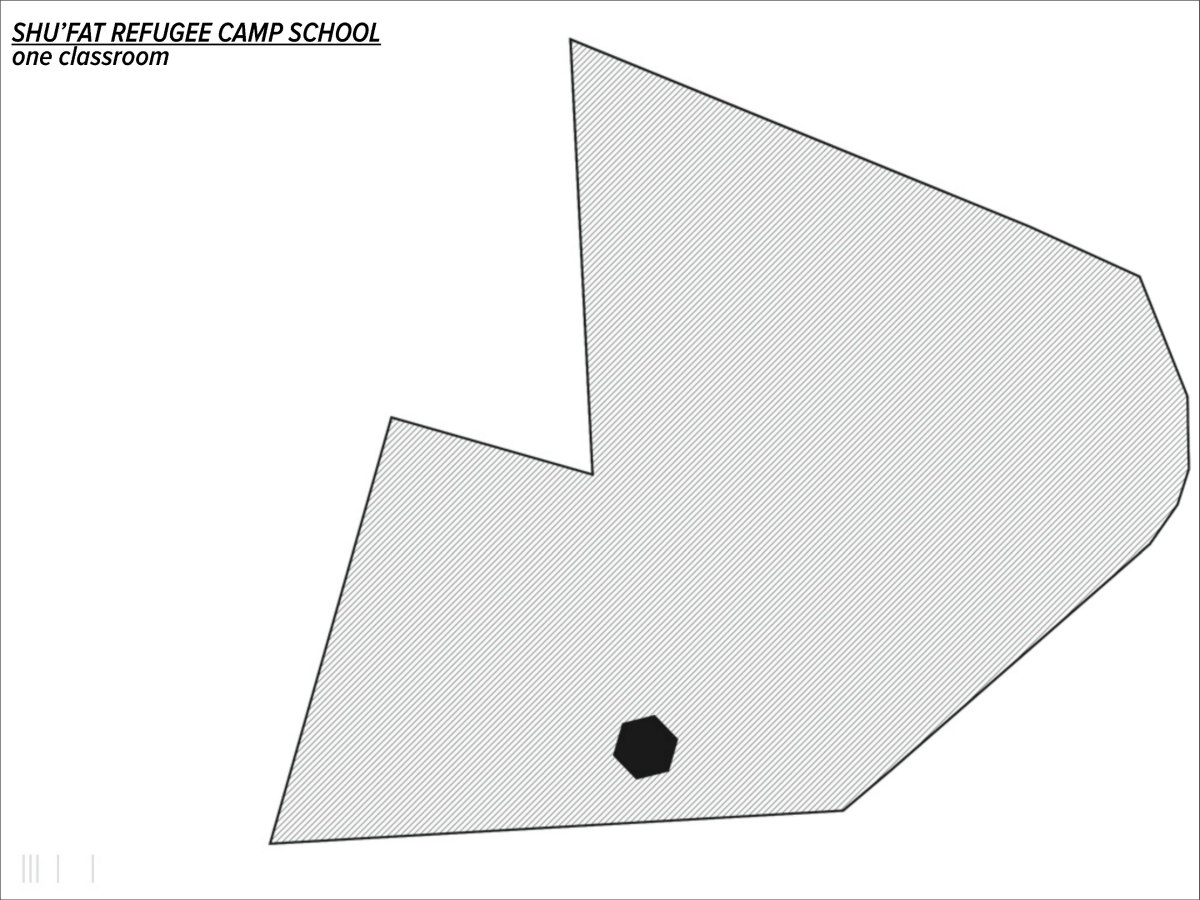

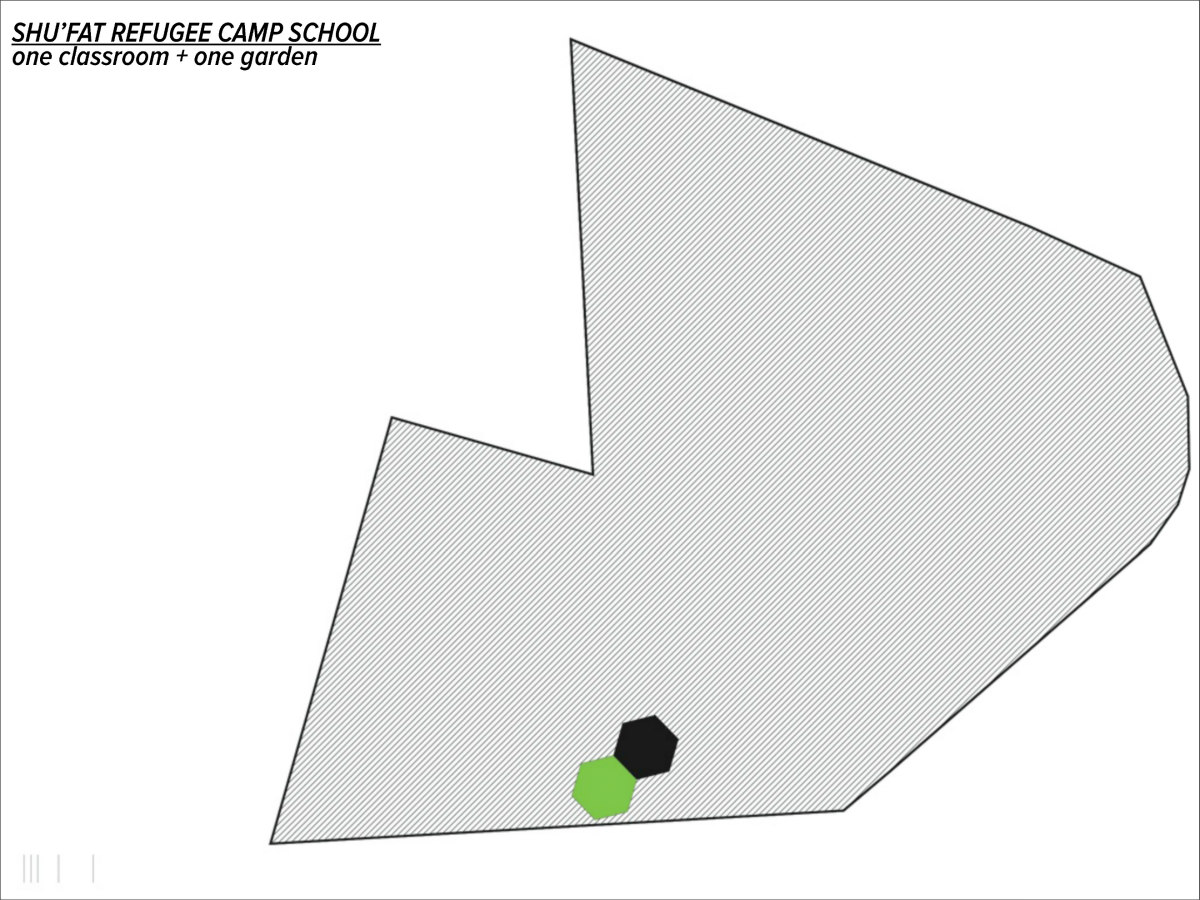

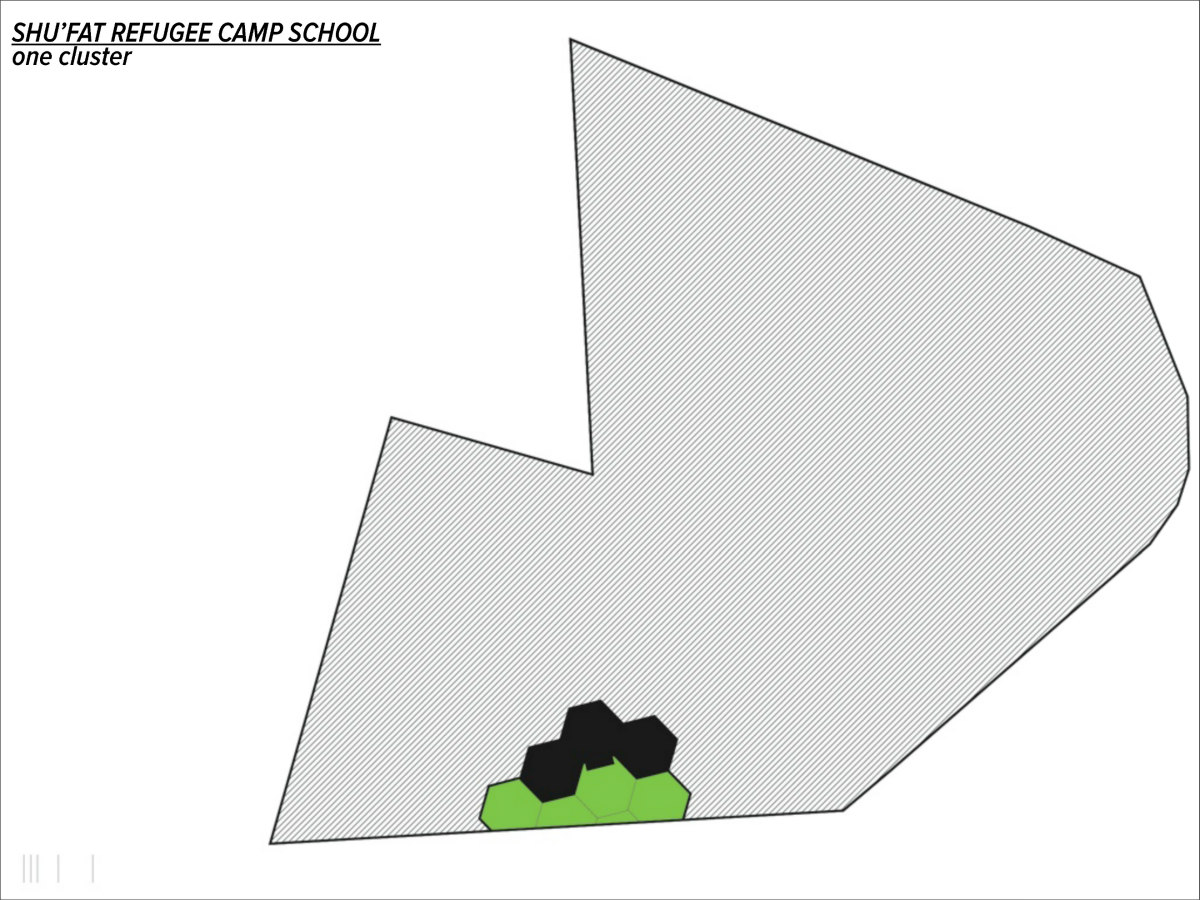

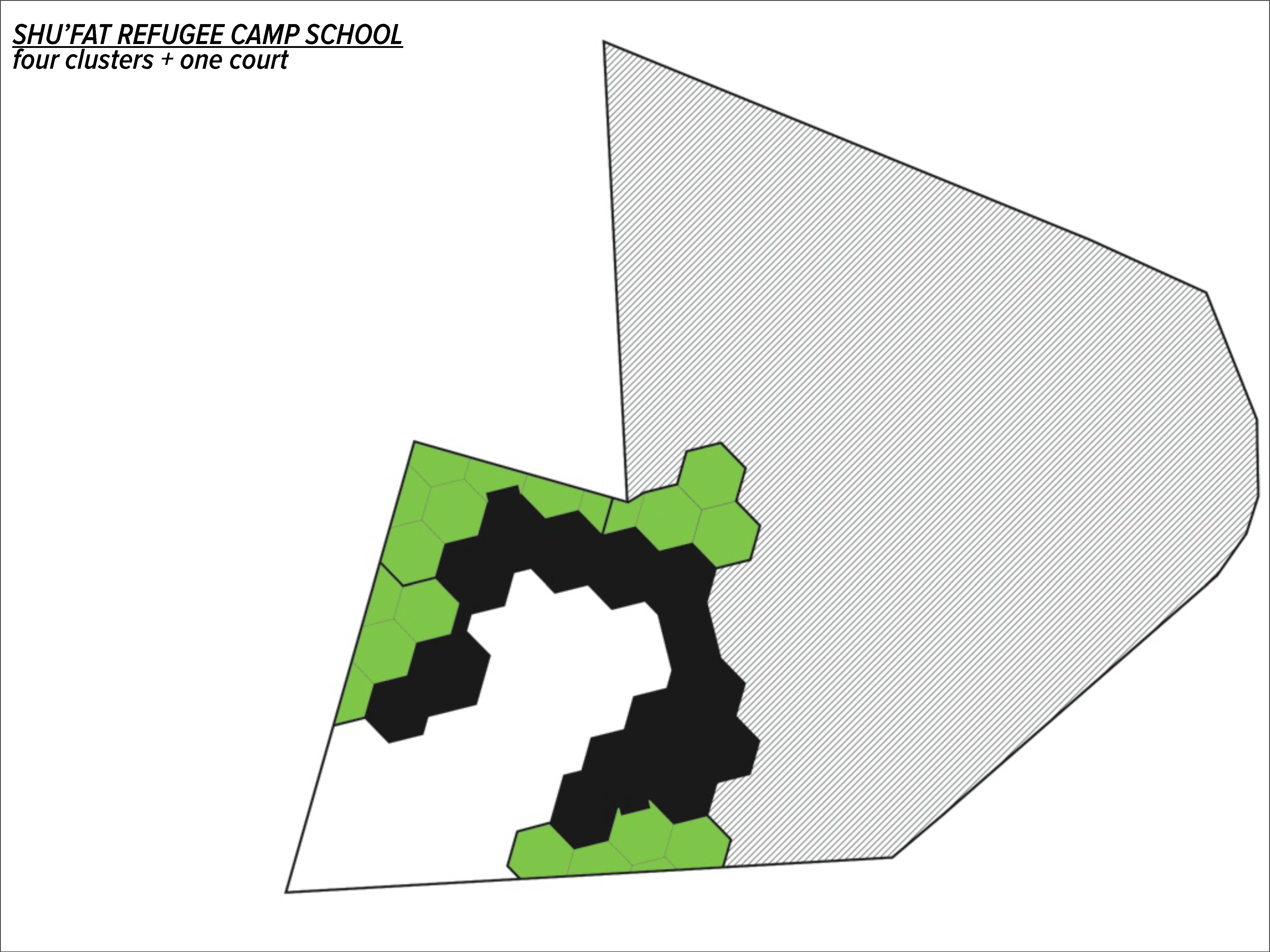

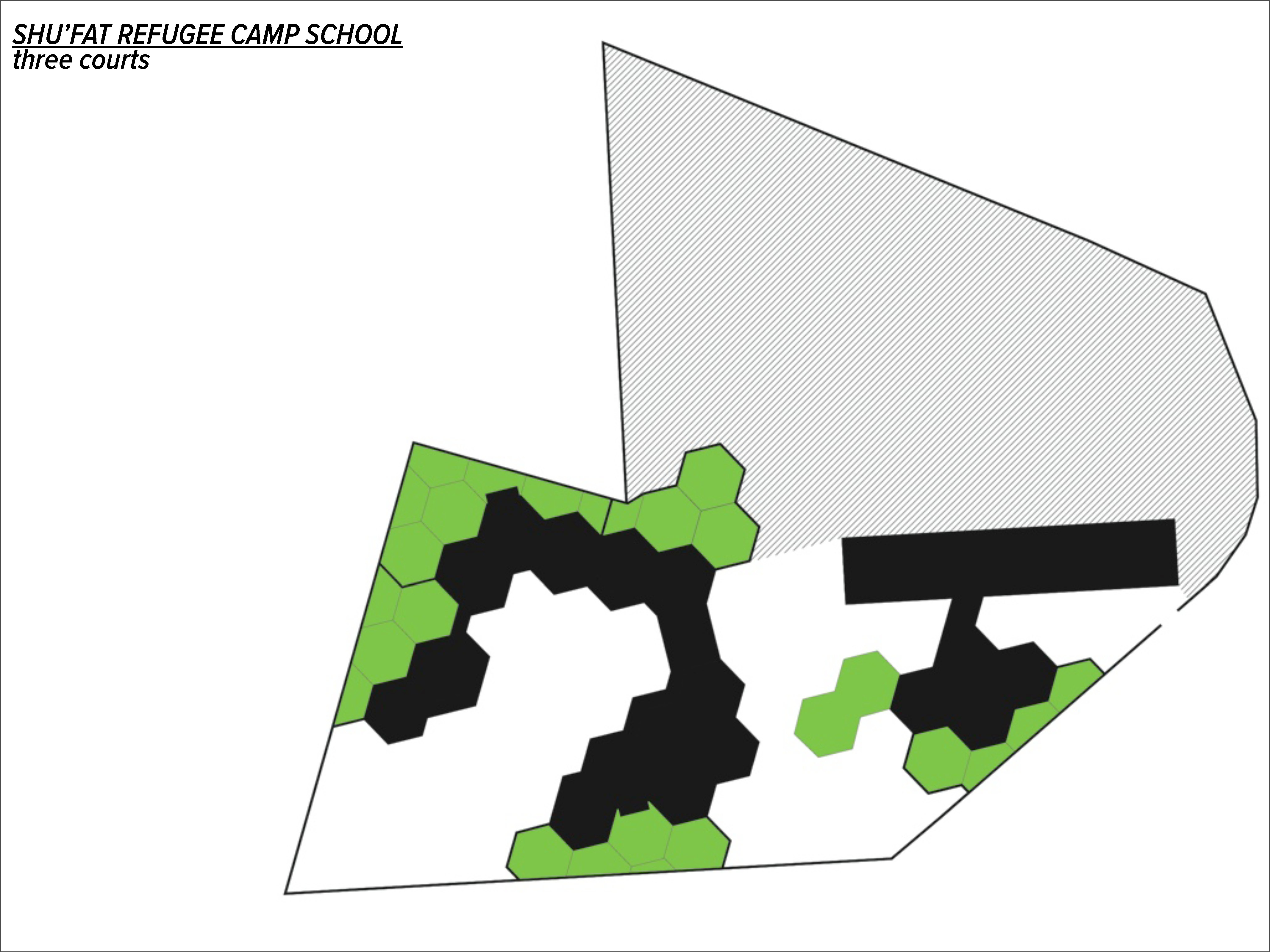

The generative form for the school is a circular space, space around which people can gather to tell or listen to a story. Architecturally, the hexagon constitutes the single classroom, a space in which each participant is equally invited to speak.

Recognizing that the camp is a spatial expression of a particular relation to another place – the place of origin – the project, instead of dismissing this relation, inhabits this tension and contradiction. We created a double for each classroom: an outside open space, a piece of land to cultivate material and the cultural dimensions of the place of origin.

For Louis Khan, schools began with a man under a tree who did not know he was a teacher, sharing his realizations with others who did not know they were students. In this pedagogical spirit, the spaces in the Shu’fat School offer the possibility for the constitution of ‘tree schools’, where people from the community could become teachers and activate community-based discussions around topics that the participants can choose according to their relative needs. The tree school is first and foremost a place of people’s gathering around a tree perceived as a living being. The tree, with its characteristic and history, is the device that creates a physical and metaphorical common territory where ideas and actions can emerge through critical, free and independent discussion among participants.

The tree school is a space for communal learning and production of knowledge grounded in lived experience and connected to communities. It brings people together in a pluralistic environment where they can learn freely, honestly and enthusiastically. It reasserts what is urgent for participants, forming an active group that chooses words, constructs meanings, and creates useful knowledge through actions. The tree school is activated around the interaction and interests of the participants and its structure is consequently in constant transformation and open in order to accommodate changing urgencies. It can last days, months or years.

The tree school reclaims diversity in ways of learning. For many, knowledge is based on information and skills; the tree school places strong emphasis on the process of learning that cuts across conventional disciplines of knowledge, moving along a different vision, one which integrates aspects of life and is in dialogue with the larger community. It welcomes forms of knowledge that remain undetected by the radar of traditional academic knowledge. They formed a Tree School, where new forms of knowledge production are made possible, when teachers and students forget that they are either teachers or students.

The first tree school was established in Bahia, southern Brazil, together with the Brazilian art collective contrafile’ on the occasion of the São Paulo Biennale in 2014. It joined together activists, artists, quilombola intellectuals, landless movements and Palestinian refugees in discussions of forms of life beyond the idea of the nation state and the meaning of knowledge production within marginalized sectors of society.

The tree school also took the form of a public installation on the ground floor of the biennale exhibition space, hosting thousands of students from São Paulo schools. At the end of the exhibition, the tree school was planted in Tainã Culture House, a central node of the quilombola network. Quilombos were communities founded by enslaved Africans and Afro-descendants who fled their oppressors and established what it later came to be known as the first democratic republic in the Americas. After the Bahia experience, we activated other tree schools in the Shu’fat refugee camp in Jerusalem, in Cuernavaca, Mexico and in Curitiba, Brazil. Over the coming years, the tree school will be activated in other contexts and with other groups who have already expressed interest: among these, a network of teachers and students from Beirut and Turkey; a group of architects in Bogotà, Manama and Medellin, who have already proposed similar learning environments in slums; and in Bangalore, India, where we want to develop a non-Western based curriculum.

With the tree school, by activating critical and egalitarian learning environments, we want to mobilize marginalized knowledge that stays under the radar of traditional academic learning. These experiments want to be in dialogue with formal educational institution in order to create new spaces for learning.

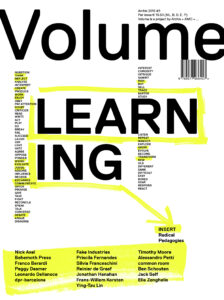

This article was published in Volume #45, ‘Learning’.