SAAL, Sweat and Tears

Portugal faced a dramatic housing shortage in the early 1970’s that contributed to the energies of 1974’s revolution. One of the first acts of the new government was to institute new housing policies and institutions, Serviço de Apoio Ambulatório Local (SAAL, Service for Local Mobile Support), that focused on promoting the right to the city through collective processes of design, construction and management. Manifesting itself differently throughout the country, SAAL was irreparably altered just a few years later due to political conflict. Since then, the fates of these architectures and their built agendas have lay uncertain. What will be the legacy of this failed proletarian utopia?

In the early 1960s, the housing crisis in Portugal was critical. In a country with fewer than two million households, an estimation published in 1963 concluded that 466,000 dwelling units were required to meet the needs of the ill-housed population. With the government’s finances depleted by the anachronistic effort to preserve the country’s colonial empire in Africa, and with the consequences to global economy created by the 1973 oil crisis, the housing shortage in Portugal aggravated further in the early 1970s. The dictatorship’s social basis of support waned swiftly. Indeed, these circumstances combined would lead to the military putsch that on 25 April 1974 overthrew the dictatorial regime that ruled the country since 1926.

These events would produce a noticeable transformation in governmental housing policies. Struggling to contain the social unrest that emerged immediately after the coup, the first provisional governments launched a new strategy to cope with the housing crisis. The Serviço de Apoio Ambulatório Local (SAAL, Service for Local Mobile Support) was a vital component of this strategy and arguably the most innovative attempt to articulate technical expertise, political institutions, and the ill-housed population. Indeed, the SAAL program became eventually instrumental to cope with the country’s housing shortage, which triggered widespread squatting movements, and public demonstrations in protest against a situation where there were so many people without houses and so many houses without people.

SAAL: Power to the people

One of the fundamental characteristics of the SAAL program was a strategy to pursue alternative forms of spatial agency, namely through citizens’ participation in the design process, and exploring the latent resources of the ill-housed population in developing their own communities. In other words, the new housing policies suggested that people should contribute with sweat equity to develop their own dwellings, partially liberating the government from the financial burden of funding the planning and construction of houses for a great deal of the insolvent proletariat.

Nuno Portas, an architect and arguably one of the most prominent Portuguese specialists in social housing, was nominated Secretary of State for Housing and Urban Development in the first provisional government. Together with another housing expert, Nuno Teotónio Pereira, Portas devised the SAAL as a housing program that contrasted with the rationale of the housing policies pursued by the dictatorial regime. While the latter was chiefly based on the promotion of home ownership, Portas and Teotónio advocated for the SAAL a social organization of the demand. Further, they attempted to rearticulate the public housing policies to cater for all income sections of the society. Hence, considering that a great deal of the urban proletariat living in substandard conditions were not financially solvable, they suggested using aided self-help solutions as a strategy to adopt the population’s sweat equity as one of the components in the funding scheme for the SAAL program.

The SAAL program emphasized the socialization of the housing process, shunning individual endeavors and encouraging collective undertakings. To secure this, the program established that the residents should be organized in housing co-operatives or dwellers’ associations to take part in the process and activate the funding scheme to finance the development of the operation. Each co-op or association should receive from the government a non-refundable subsidy for each new dwelling unit developed, an amount equivalent to 15/20 times the minimum monthly wage in Portugal in the mid-1970s, enough to cover one-fourth of the building costs of an affordable two-bedroom house. Next to it, the co-op or association should finance the operation through a soft-loan granted by the government, and payable in monthly installments over a period of twenty-five years. Regarding land tenure, the municipalities performed a central role, lending existing properties, or expropriating and taking possession of private land to develop the operations. Further, they were also responsible for the development and maintenance of infrastructure. The co-ops and the residents associations could thus occupy municipal land as long-term leaseholders.

In this context, self-help was seen as a strategy to employ sweat equity as a complement to the governmental subsidy, thus reducing the outstanding debt and emancipating the inhabitants from their dependence on institutional support. This strategy was indeed a reenactment of initiatives that gained momentum in South America in the 1960s, and that eventually became currency in the housing policies sponsored from the 1970s on by the United Nations and the World Bank. To be sure, Nuno Portas was well informed about the work of the Peruvian architect Eduardo Neira, about John Turner’s vision of squatter settlements as an architecture that works, and about the work in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas by the Brazilian urban planner and anthropologist Carlos Nelson Ferreira dos Santos, to name but a few of the most prominent supporters of self-help.

Notwithstanding Portas’ good intentions in suggesting self-help as one of the fundamental principles of the SAAL program, the use of sweat equity in the development of the housing operations was far from being a consensual aspect.

Sweat: The Politics of Self-help

Portas and his collaborators devised the so-called Brigadas de Construção (Construction Brigades) as an essential instrument to implement the SAAL program. They would become the mediators between the population, the municipalities and the government. Moreover, they should have a great deal of institutional autonomy to allow them to perform more as interpreters of the people with the governmental agencies than the other way round. Nevertheless, the ideologues of the SAAL program highlighted that the Brigades, although supportive of the people, should not replace them or their representative organizations. The brigades should thus limit their intervention to technical aspects.

This emphasis on the technocratic role of the brigades testifies to the uncertainty of the political climate that Portugal was experiencing in the post-revolutionary period. In order to avoid a political contamination of the SAAL program that could undermine its implementation and a productive relation between the main stakeholders, it was then important to stress the role of the technical brigades as nonpolitical entities. This goal failed spectacularly, though. One needs only to read the Livro Branco do SAAL (SAAL’s White Paper), published in 1976, to acknowledge the extent to which the SAAL process was politically charged.

For one thing, as regards the implementation of self-help as part of the SAAL operations, there were different accounts, all politically motivated. In a press release of the representatives of the SAAL/Norte operations, written in December 1974, they contended that “the [SAAL] answers […] to a concern on the immediate engagement of the less solvable social strata in self-help housing solutions, which can avoid the dislocation of the inhabitants far away from their traditional forms of living in the city or in the human settlement.” However, as the process moved along, this initial premise would be swiftly reconsidered, and rejecting self-help housing strategies eventually became a battle cry for a great deal of those involved in the process.

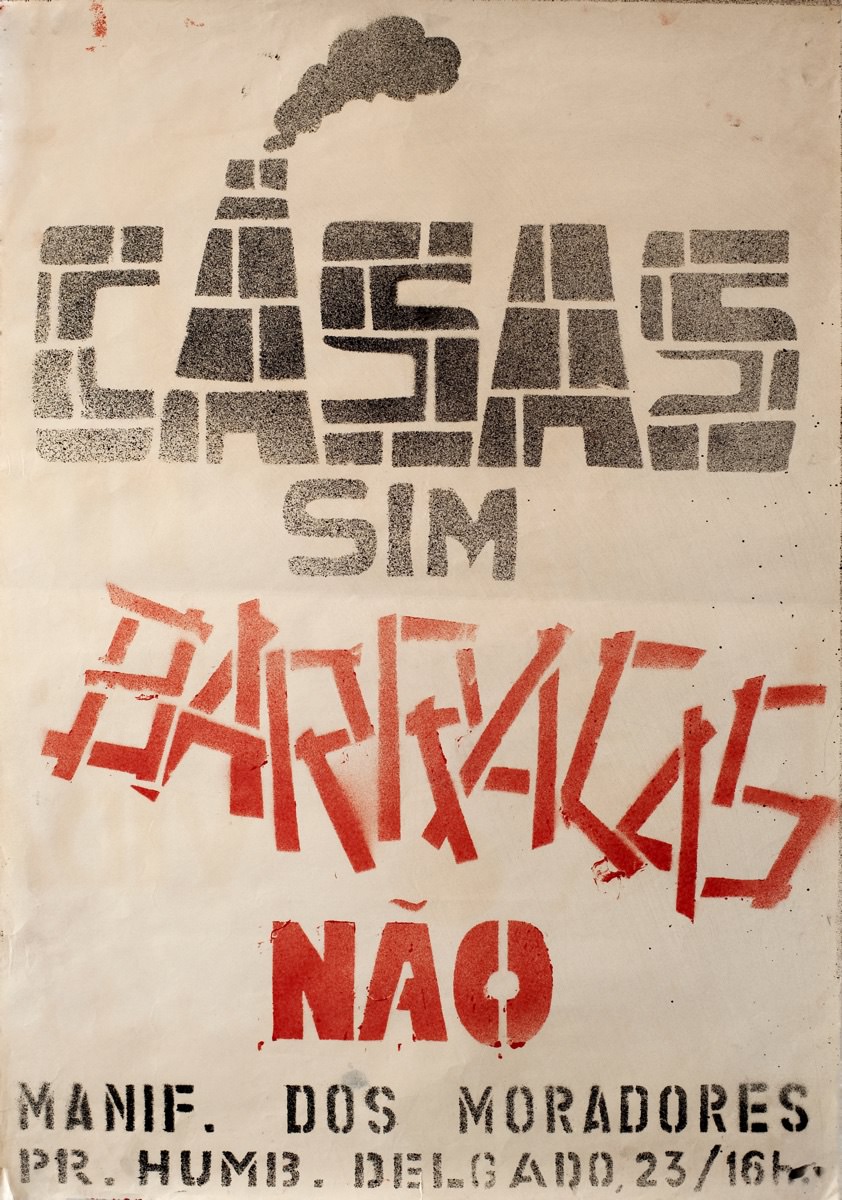

In the manifestos, letters, posters and banners produced by the SAAL brigades, the expression ‘Casas Sim, Barracas Não’ (which roughly translates as ‘Houses Yes, Slums No’) became a mantra and a battle cry in the struggle against the governmental policies that allegedly threatened a progressive housing policy. While there was a keen interest among the people in expressing the right to the city and socializing the housing policies, there was an explicit refusal to use sweat equity. For example, in a “charter of claims” written on 15 February 1975 by the joint commission of dwellers’ associations of Lisbon’s slums, they contended that “self-help housing, which is the residents themselves building new houses, is nothing but a form of double exploitation. After a long day of work, filling the pockets of the capitalists, we would have to stay until late hours working in building the houses.”

While the criticism on self-help methods was already growing at the beginning of 1975, after the failed counter-revolutionary coup of 11 March 1975, the political overtones of aided self-help housing became much more noticeable. This can be testified by the position of the Trotskyist party, Liga Comunista Internacionalista (LCI, Communist Internationalist League), formulated on 15 May 1975, where they declared: “No to self-help housing. Enough of using the workers’ shoulders to support the crisis of capitalism.” The nature of this statement would swiftly permeate into, and resonate with the positions held by the SAAL brigades, namely those operating in Lisbon. In effect, one of the conclusions of the plenary meeting of the Lisbon Brigades for Local Support, held on 26 May 1975 was that “the SAAL operation shall not be committed to self-help housing”.

The resistance to self-help housing solutions gained momentum both in Lisbon and in Porto, though there was a more lenient account of its qualities in the periphery of the political battlefield. To the south of the country, in Algarve, the brigades coordinated by José Veloso developed architectural solutions that were designed to integrate self-help in the construction process of neighborhoods to accommodate communities of fishermen. The documentary Continuar a Viver ou Os Indíos da Meia Praia, (Life Goes On or the Meia Praia Indians), directed in 1977 by António da Cunha Teles, shows different moments of a SAAL operation being built on the outskirts of Lagos, by the seaside. In this film, one can observe the blurred limits between the performance of the architect as a technician, and the role of the architect as a political activist. Rather than debating the emancipatory or alienating nature of self-help housing strategies, José Veloso and the SAAL brigades operating in Algarve pursued a pragmatic approach in which sweat equity was instrumental to foster the collaborative effort of the community of fishermen in developing the operation using the limited financial and material means available.

In the SAAL Algarve operations, self-help housing was used as a vehicle to socialize the production of space. In Lisbon, the SAAL program was integrated in the existing bureaucratic apparatus of the municipal housing agency. As a direct consequence of this administrative decision, the outcome of the SAAL operations in Lisbon is sharply in contrast with that elsewhere. Indeed, despite the recognizable quality of some of the projects developed in Lisbon, they were less disruptive of the status quo than those built in Porto or in Algarve, for example. As one architect involved in Lisbon’s SAAL operations put it, when the technicians asked the people how did they want their houses to be, they replied: the same as yours! Their references were, of course, those of the urban middle class, who lived in apartment blocks in the city center. In fact, the main SAAL operations in Lisbon were designed as multistory housing blocks, though located on the periphery of the city. They were usually developed in cheap land expropriated next to existing slums (the bairros de lata), which were demolished to make way to a completely new housing figure, in sharp contrast to the vernacular spatial and social practices of the bairros de lata.

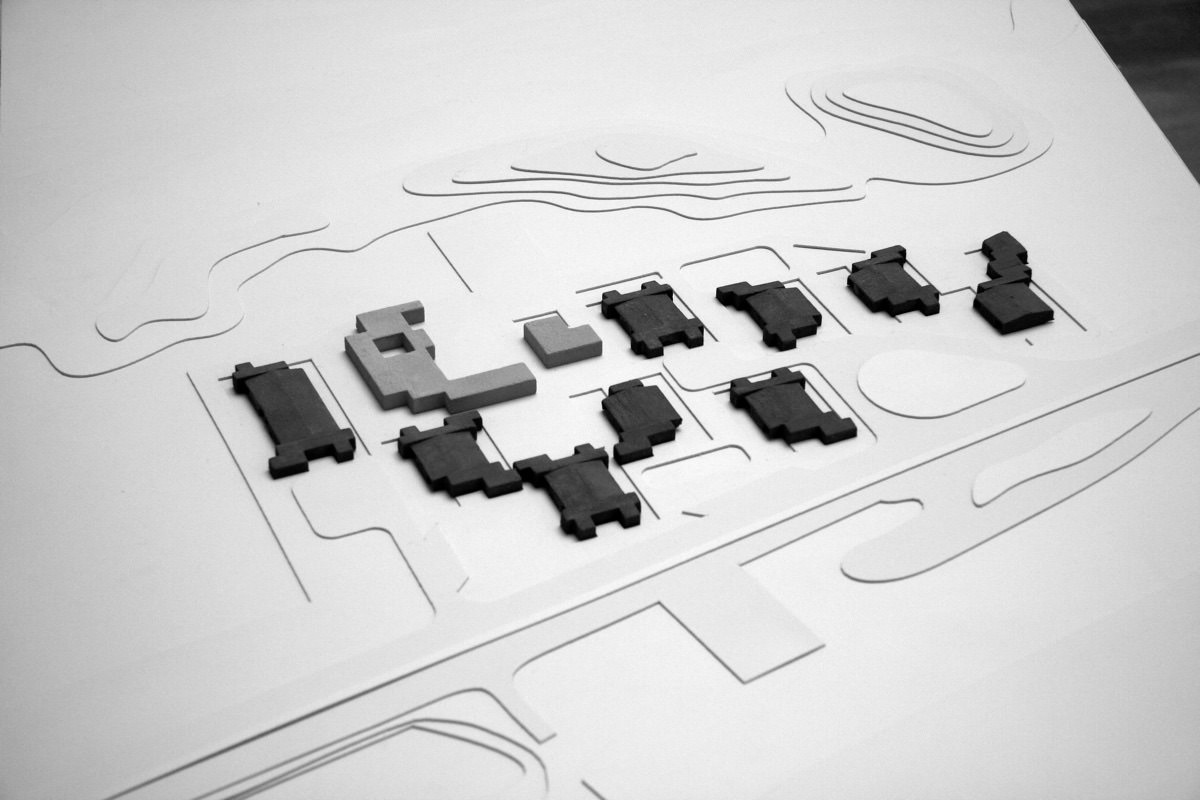

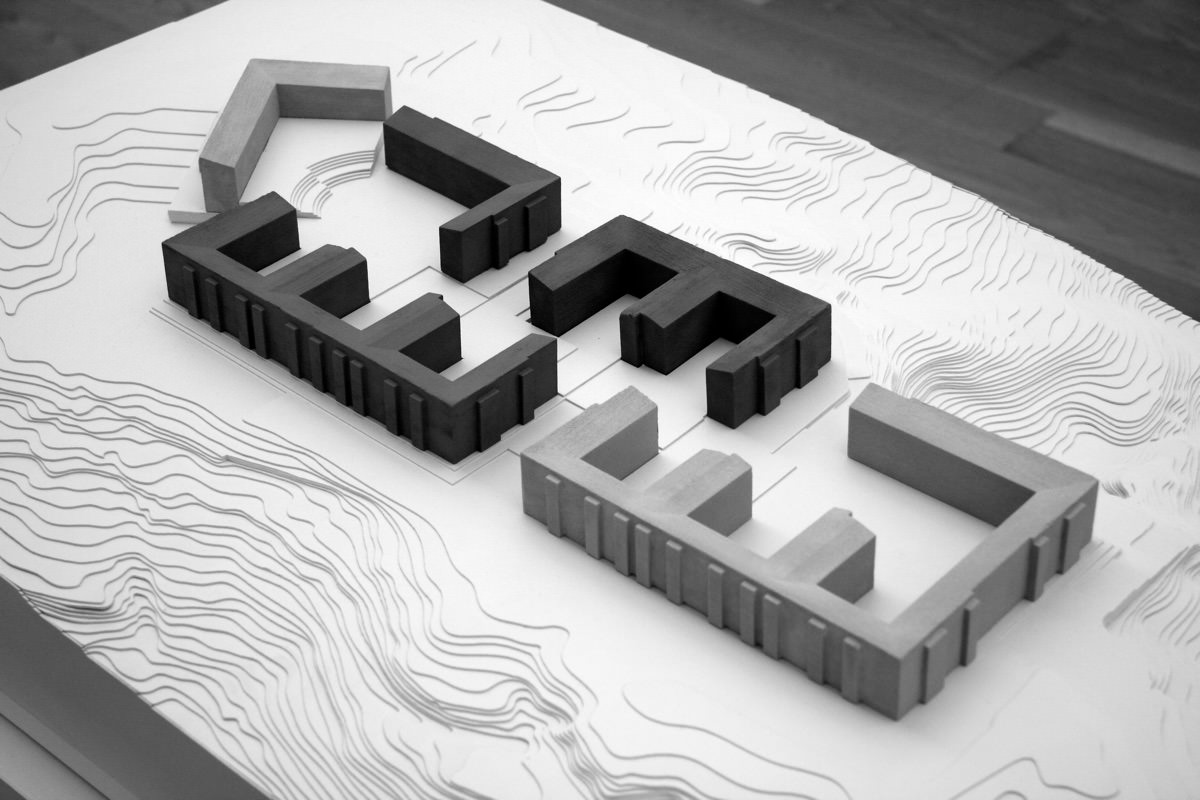

In Porto, the disciplinary approach took a different way from that in Algarve and in Lisbon. The technical brigades were militantly engaged in giving people the right to the city. As opposed to the suburban character of Algarve’s and Lisbon’s slums, in Porto the working class lived in the city center, in proletarian islands (the so-called ilhas). The ilhas were usually built in the middle of the blocks, in the courtyards of the houses of the middle class, who were actually the owners of these substandard dwellings. Secluded from direct participation with public space, the ilhas were nevertheless a housing scheme that fostered the development of well-knit social networks, strongly based on communitarian values, where small row houses shared a collective outdoor space and basic sanitary facilities.

In the mid-1970s, as a consequence of the drastic increase of their land value, real estate interests threatened the existence of the ilhas, as they were no longer important as the locus for the reproduction of labor. In this context, showing its dependence of, and subservience to, the power of the capitalist apparatus, Porto’s municipality approved in the 1960s a slum clearance process, relocating the residents of the ilhas to social housing complexes built on the city’s periphery. However, while before the revolution the residents were enforced to accept the relocation to the periphery, after 25 April 1974, the residents of the ilhas asserted their “right to the place”.

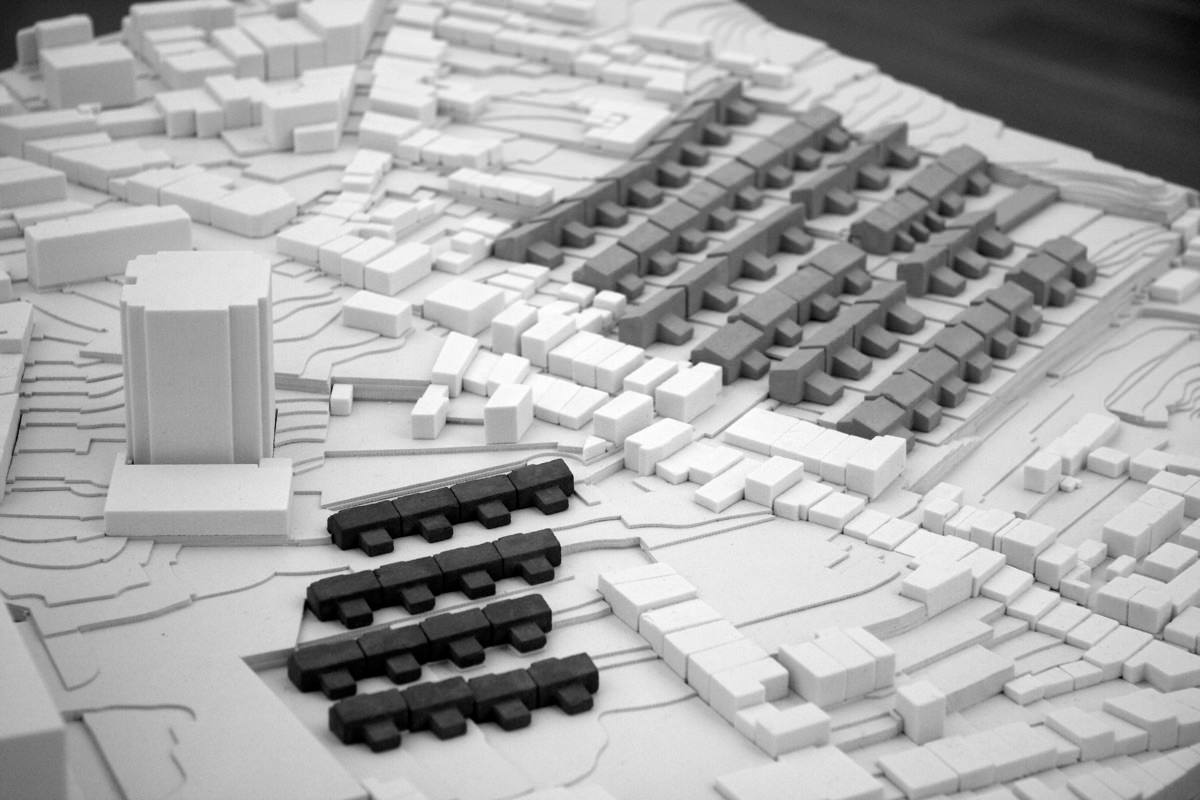

The SAAL technical brigades followed suit and praised the ilhas as a model of community life. It comes as no surprise, then, that the morpho-typological qualities of the ilhas contributed significantly to create the toolbox used by the architects engaged in Porto’s SAAL operations. Despite this deliberate attempt to rehabilitate vernacular social and spatial practices, the brigades rejected self-help as a methodology to build the new settlements. They considered that it jeopardized the quality of the whole. In fact, Álvaro Siza, one of the architects involved in Porto’s SAAL operations, quoted Che Guevara, claiming that “quality is respect for the people”. Despite this rejection of self-help as a strategy to build the initial complex, many architects, including Siza himself, designed schemes that suggested (deliberately in some cases, subsumed in others) possibilities for incremental growth and change over time.

Tears: Appropriation and Dilapidation

As the political situation in post-revolutionary Portugal unfolded, so the fortunes of the SAAL operations would be defined. For two years, the country lived in permanent social, economic, and political turmoil. There were six provisional governments until the first democratically elected government was installed in July 1976. This institutional “normalization” created the conditions for a reorganization of power relations that ruled in the country before the 1974 coup. A few months after the new cabinet was formed, the government decided to reorganize the SAAL program, altering the financing scheme and handing the management of the processes to municipalities, whose leaders were about to be also democratically legitimated.

The government’s keen interest in shifting the coordination of the SAAL process to municipalities, though seemingly underpinned by their democratic legitimacy, concealed a hidden agenda. On the one hand, the relation between the SAAL brigades and the population created short circuits in the social and political system. The challenges tackled by the brigades were not only technical or disciplinary issues, but also political. Their approach resonated with a system of ‘dual power’ that jeopardized established power relations cherished by the political apparatus gaining momentum in the aftermath of the revolution. On the other hand, after the relative stabilization brought about by the new constitution and the first free elections held on 25 April 1976, the reorganization of the pre-revolution capitalist apparatus unfolded swiftly, and its influence soon infiltrated the operation of public institutions, especially at the municipal level.

Once under the responsibility of the municipalities, only those parts of the SAAL operations that had already started were actually finished. Usually the buildings were erected with poor or no infrastructure at all, thus contributing to their ghettoization, and to spark a general discontent and disbelief among the residents in the SAAL process. This situation was, obviously, good news for the political and economical interests of those that saw the SAAL process as a menace to the traditional power relations and to the business as usual of the real estate market. The era of ‘dual power’ was over. For those engaged in the technical brigades and for the people involved in the SAAL process, it was now time to shed tears over the waning utopia of creating an inclusive city.

Throughout the last three decades, the SAAL neighborhoods evolved disparately. There is, however, a resonance between the different housing figures used in the development of the operations and their current state. In Lisbon the municipality integrated the SAAL operations that used the figure of the multistory block in the infrastructure of public space, where they now stand next to ‘regular’ affordable housing schemes. However, the dilapidation of the buildings, which were designed with a keen refusal of self-help initiatives, testifies to the predicaments of the ambiguous tenure system adopted in the SAAL program. After paying the debt to the government, the co-ops and housing associations own the buildings, but not the land, which belongs to the municipality, that leases it for free. To preserve the right to occupy their flats, the occupants pay symbolic membership fees to the co-op or to the residents’ association, an amount that is clearly insufficient to promote regular maintenance and preservation of the housing complexes.

In the SAAL operations that developed schemes influenced by vernacular social and spatial practices, the process unfolded differently. Taking advantage of schemes chiefly based on the row house type, both in Algarve’s as in Porto’s SAAL operations, there was a great deal of transformation over time triggered by self-help initiatives. Indeed, the spatial agency of the residents in the planning and construction of the settlements continued over time, and today the neighborhoods exhibit pervasive signs of appropriation and vernacularization. In both cases, the realm of the domestic shows personal investment and caters for individual representation and expression. Concurrently, the realm of the collective shows clear signs of degradation with few signs of the social organization that Portas sought for these settlements. Rather, they evolved detached from the infrastructure of public space, as islands in the urban fabric of the city that deliberately kept them apart.

The evolution over time of the SAAL neighborhoods delivers a poignant picture of the difficult relation between individual agency and collective engagement. It shows the emancipatory potential of self-help initiatives, and it also illustrates the importance of preserving the realm of the collective. While the importance of citizens’ participation in the design decision-making process is vital, the role of the expert cannot be disregarded, as it may be used to trigger emancipatory forms of self-help.

This article was published in Volume #43, ‘Self-Building City’.

This article was published in Volume #43, ‘Self-Building City’.