Reports from the front

Interview with Hans van Dijk

In revisiting Volume’s (pre)history In Volume 58: The Legacy, we conducted an interview with Hans van Dijk, editor-in-chief of Volume’s predecessor Archis during the 1980s. An exchange on the role of architecture criticism in general and the magazine in particular at the time. The sad news that Hans van Dijk passed away August 26, 2021 transforms this exchange between colleagues in search of motives and motivations into a testimony of what architecture criticism once stood for and what it may potentially be capable of today.

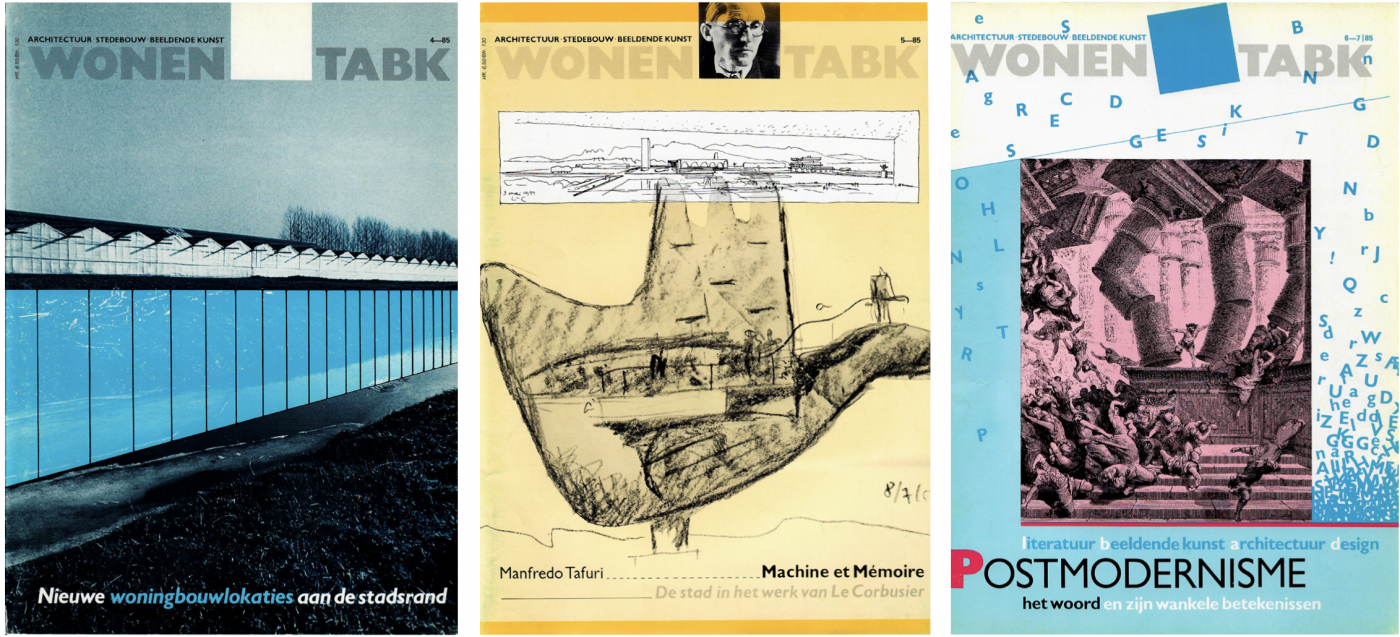

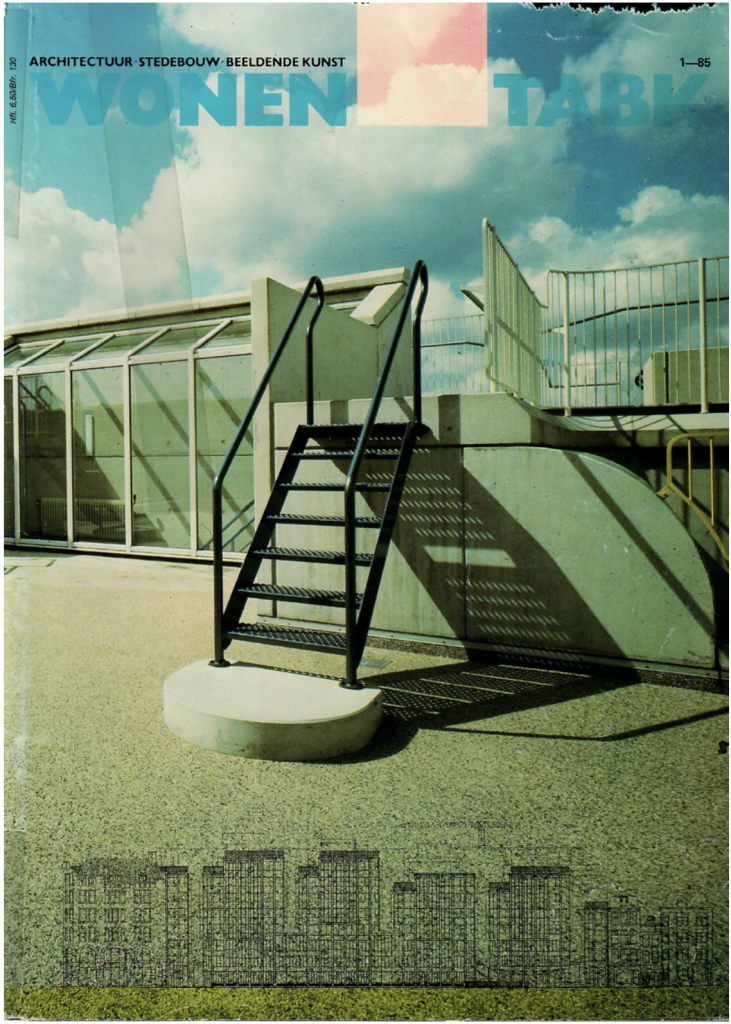

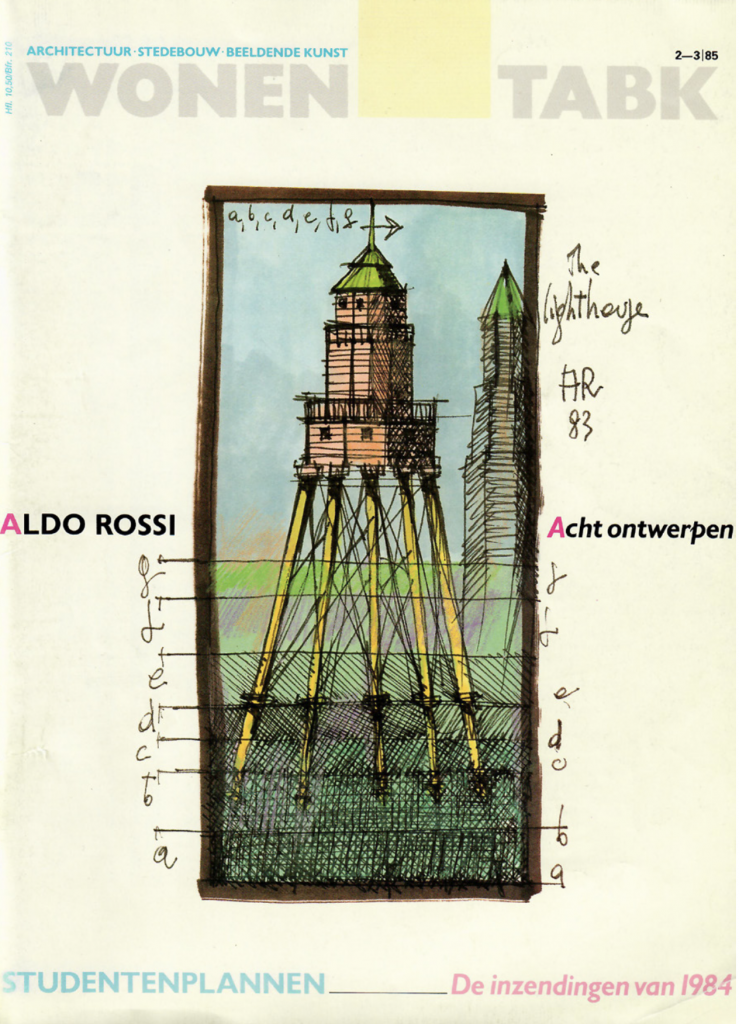

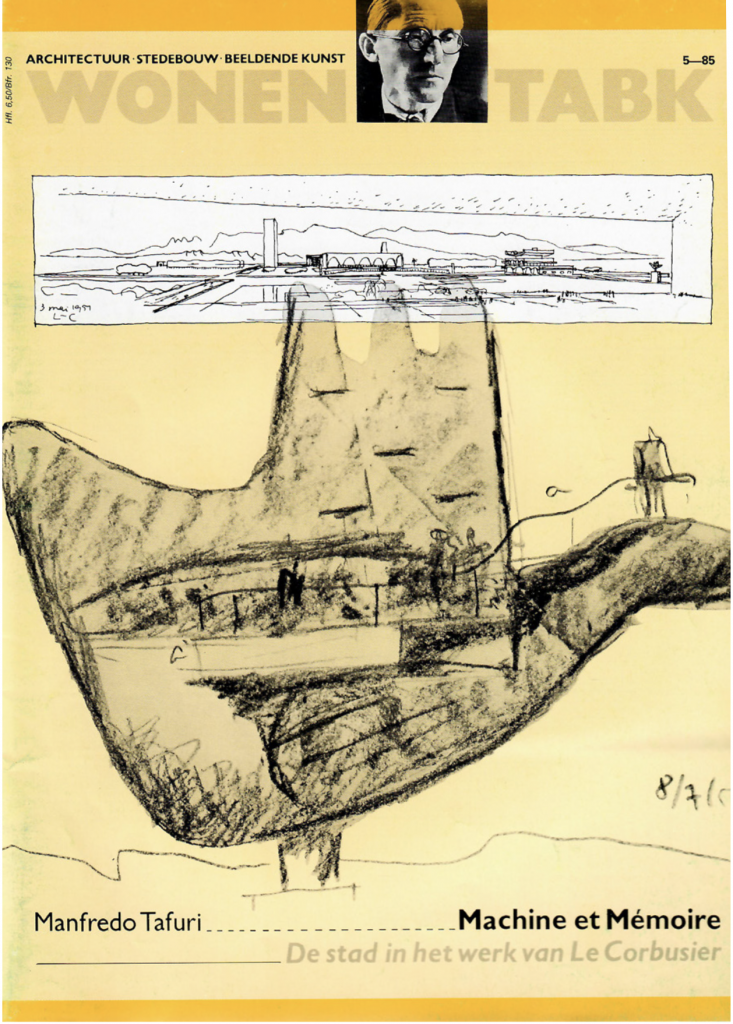

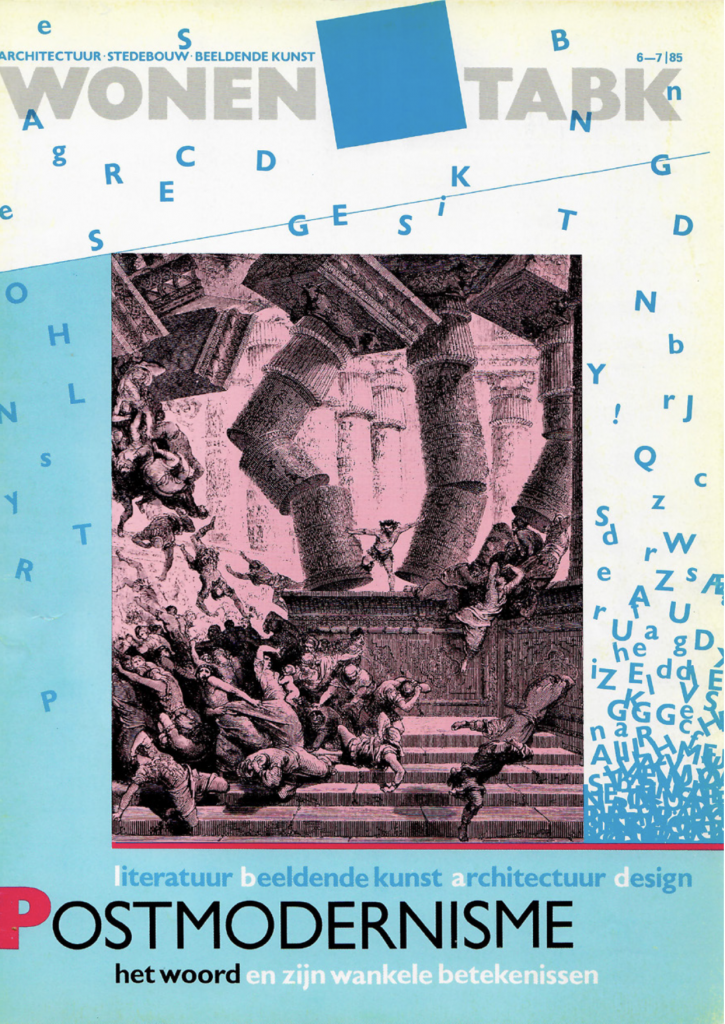

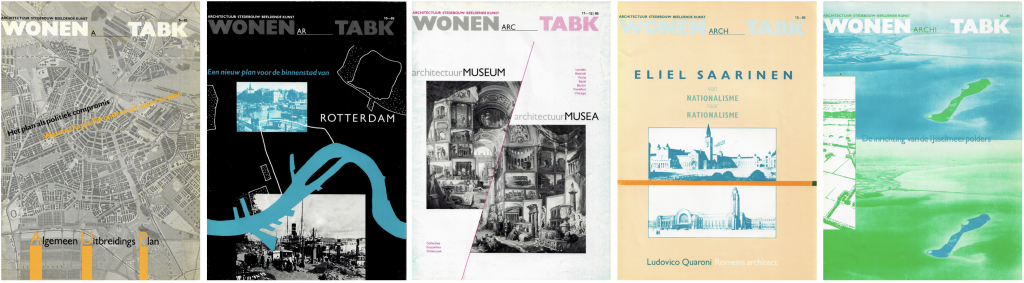

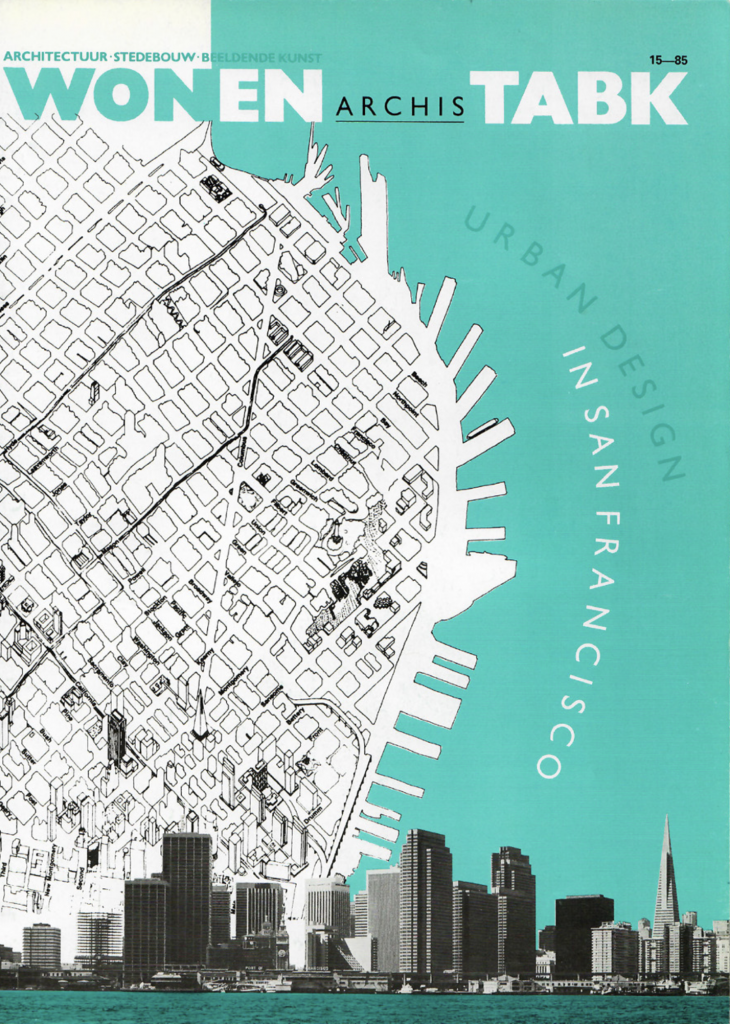

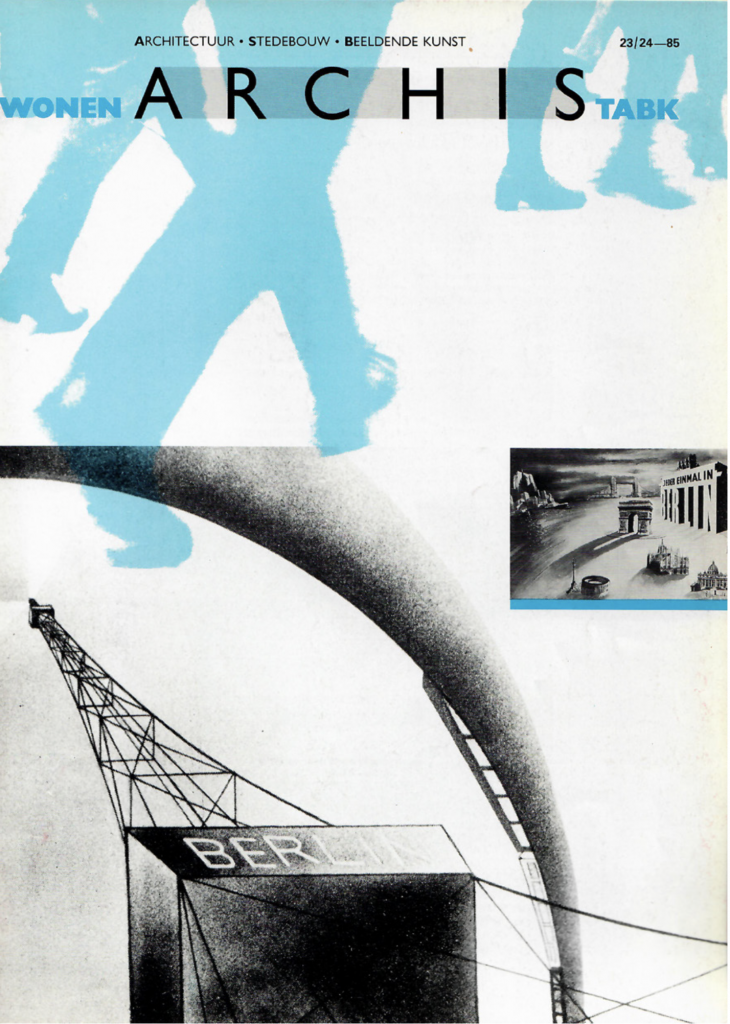

As editor-in-chief of Wonen-TABK in the mid 1980s, Hans van Dijk not only set in motion its transformation into Archis (from fortnightly to monthly, twice as thick, bigger, better paper, part color), he also steered the magazine away from the sociologically dominated profile of the 1970s towards one in which the discipline of architecture was front and center. This immediately opened the way to a stronger international orientation, allowing movements and oeuvres to be subjected to scrutiny: where was the energy to be found, where was the debate taking place, and who were the trendsetters? The magazine as the intermediary between what was happening in the Netherlands and what was going on in the wider world. That international approach also had implications for the language of communication. Eventually this resulted in Archis, which had meanwhile become part of the new Netherlands Architecture Institute, becoming a wholly bilingual (Dutch-English) publication in 1993. But that was still far in the future when Hans van Dijk joined the editorial staff of Wonen-TABK in 1980. During his years at TU Delft (1968-1978, Architecture), architectural theory was steadily gaining prominence as an independent ‘element of the discipline’. Students and research assistants immersed themselves in histories, writers, and philosophies that many professors had never heard of and ‘basic translations’ of these French, German or Italian works were circulated to make them accessible for other students. The architect as the lackey of capitalism was on the way out to be replaced by the architect as social worker for the oppressed of the earth. Or maybe not?

Hans van Dijk was editor-in-chief of Wonen-TABK from 1981 to 1985 and subsequently of Archis from 1986 to 1990. During his Archis years, he also (co-)initiated the Netherlands Architecture Yearbook, selecting best projects each year. After leaving Archis and as a staff member of the Netherlands Architecture Institute, he became responsible for ‘special productions’, setting up conferences, debates, and publications. After a brief return to the editorial board of Archis, Hans van Dijk became assistant at TU Delft’s Faculty of Architecture in the mid-90s. He started his PhD there, focusing on postwar architecture critics, which he couldn’t complete.

Let’s go back to the moment when you walked into the editorial offices of Wonen-TABK on Leidsestraat in Amsterdam, in 1981 if I’m not mistaken.

I was taken on as editor and a year later I became editor-in-chief. Looking back, my years at the magazine were some of the happiest of my life. There was a team spirit; all the people there had been chosen because they were independent, with opinions of their own and an ability to express them on paper.

In effect you took over from Ruud Brouwers which meant you had to deal with what he had built. He had organized the merger between Wonen and TABK, put his own stamp on the magazine, and plotted a course for it. That course can in my view be explained in light of what was happening in the 1970s. It seems to me that the magazine had a strong agenda-setting role: very socially engaged, focused on the city and the decline of the city, and on what needed to be done about that.

It was an umbrella for ‘building for the neighborhood’ and the urban renewal generation.

Then you came on board and you had to engage with that situation. What did you think back then?

Fortunately, Ruud himself was well aware that times were changing. We weren’t going to withdraw from certain areas or discard things, but we were going to put the emphasis on the significance and the value of spatial design: architecture, town planning and landscape architecture. Some of the editors were sociologists whom I already knew from Delft. In the meantime, some sort of schism had emerged between the burgerlijke and kritiese (read, academic and interventionist) sociologists. The latter’s influence was felt not so much in the department of sociology (a compulsory exam subject) as in the field of architectural research – things like housing satisfaction and so on. They issued scientifically sound and verifiable pronouncements about housing preferences and the like. Surrounding them were more people who had specialized in the sociology of dwelling. Two of those were also on the board [of Stichting Wonen] and on the editorial staff of magazine. We also looked to Plan, the organ of the architects’ association, BNA. So we were busy trying to position ourselves. But meanwhile I was wondering what to do with those sociologists. I didn’t have much use for them and so we parted company.

And what did that mean for the magazine? There were some cancellations, but there were new subscribers too.

So you eased ‘sociology’ out so to speak; or perhaps sociology eased itself out, its power over spatial design was already on the wane. In theory that should have left a vacuum, but there was no vacuum, the magazine continued, and you shaped and steered it. So which elements did you feel needed more emphasis?

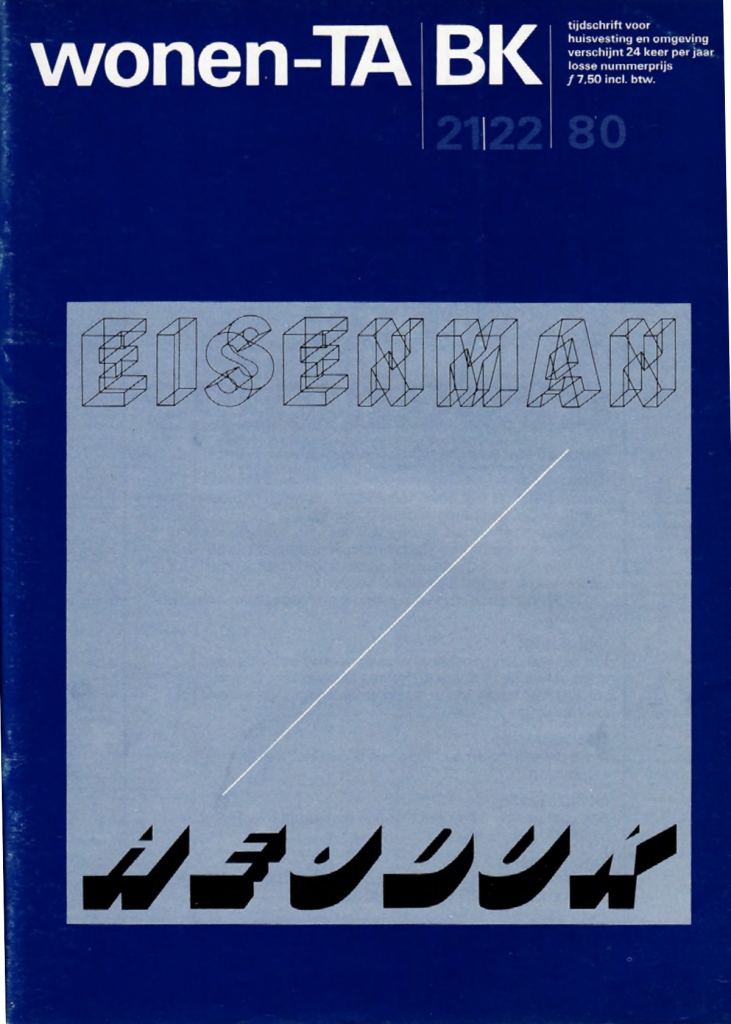

If you ask me now what my main reference points were, they were Peter Eisenman with his magazine Oppositions and beyond him the institute he was setting up [IAUS in New York], and Rem [Koolhaas]. I knew Rem already from Delft in 1977 when he was researching the Bijlmermeer with his students. Another friend was Gerrit Oorthuis, who was incredibly well informed about Russian constructivism and Mart Stam, which is how he got a job in the history department. So I brought that discussion and history into the magazine plus a couple of personal interests, things I hadn’t seen covered before but was keen to tackle in some way: critical regionalism, Robert Venturi and his magnum opus Learning from Las Vegas. I heard all sorts of things from pre-OMA Rem in Delft during the Friday post-lecture lunches. I didn’t have much affinity yet with the AA in London at that stage.

But it was clear to me from those conversations about New York that something interesting was going on there with Oppositions. A discussion about architecture combined with a lot of history: like articles from Stanford Anderson about Behrens – over three issues; they were chipping away at the foundations of the canonical history of architecture.

The intellectual curiosity of Eisenman and Koolhaas was a huge source of inspiration for me. I still think it’s important that their voices be taken seriously.

When I look at those early issues I note that your arrival coincided with an interest in design that hadn’t really existed before. There had been an interest in urban sociology, in plans and systems. But while that sort of thing occasionally involved an architect, there was no interest in what designers actually do, in their way of thinking and how they position themselves. You introduced that. Along with monographic issues on Alvaro Siza, a couple of times on Rem/OMA et cetera.

And I see connections with shifts in architecture itself, with the autonomy debate that succeeded the Marxism debate. And you brought that to Wonen-TABK. So I wonder whether that happened spontaneously or whether it was a more deliberate decision on your part.

It’s nice to hear you say that I played a kind of pioneering role as editor-in-chief. I did it for my own pleasure, which struck me as doubly advantageous for something that became my profession. When you do something for the pleasure of it you hope that something of that pleasure will also rub off on others. We were more or less free to do whatever we wanted with that magazine. But there was never a programmatic purpose behind it. You have to grasp things in a journalistic way and then write it down so that somebody else can grasp it as well. And not pepper your text with references to theorists or philosophers. I tried to read those people and that has probably been reflected in my argumentation now and then, but I never invoked an authority. The whole discussion about directing the course of architecture or changing the direction of a conversation about architecture, about where it should go, or setting agendas for architecture… I follow it all, but I don’t think I would have the presumption to engage in that conversation.

I understand what you’re saying but there’s no need for false humility. The fact that you turned the spotlight on Eisenman and Koolhaas and several other interesting figures who made a relatively autonomous contribution to architecture…

Yes indeed!

… that was a question of choice. Literally putting it in the magazine is an example of agenda-setting.

It was reflected in the cancellations and new subscriptions, too: you’re busy building a readership. People used to say, “I’m a member of Wonen-TABK”. That surprised me at first. It smacks of the collective, a party, a church. I didn’t want any congresses or Wonen-TABK tours.

If I extend that late 1980s line through to the late 1990s then, simply put, the sociological emphasis of the 1970s was succeeded in the 1980s by a greater interest in the artistic value of the design. A different kind of interest in the significance of form in society. That also allowed scope to talk about an oeuvre, identity those sorts of issues. That continued well into the 1990s and maybe even into the 2000s. That was perfectly justifiable. At the same time, so many other things that impact on the spatial design and on the reality of what surrounds us were occurring, that the focus on the architect and the oeuvre no longer sufficed. That was a shift I experienced for myself as an Archis editor. What is your take on that based on your experience of making that magazine?

I think it also came in part from the architectural world itself. A certain aversion to the mythologizing of the architectural profession. They were always saying: yes, we’re well over the 19th-century genius cult. But there was always a finger-wagging warning against ‘an excess of arrogance’ with the 2000s seen as the beginning of the Postcritical era, ushered in by the Doppler Effect essay by Bob Somol and Sarah Whiting [in Perspecta no. 33, 2002].

But it’s also got something to do with the fact that were few architects who dared to launch an intellectual project and to found their own school. I once wrote a piece about the starchitect versus the master.1 Was Louis Kahn the last master and was Aldo van Eyck still a master, but when did the star(chitect) begin then?

There was a lack of any polemicizing or postulating or agenda-setting in architecture itself, fanatical or otherwise, that one could go along with or find fault with or tear to pieces, which also precluded the emergence of a central theme in that architectural discourse. At any rate, it was one of the reasons why I went back to those old architectural critics.

Let’s segue to the architectural critics you are studying. That shift away from what is happening in society, along with a somewhat changing definition of the architect’s role therein, plus the reduced plausibility of seeing the architect as the Great Designer of the universe, also introduces the problem of communication. It’s easy enough to tell the story of Rem Koolhaas and in so doing put a number of social and possibly political issues on the table and clarify them for the general public. But when you’re no longer able to hang that narrative on a figure, to something tangible and recognizable it’s a massive task to put the story across. It’s a problem that ‘architectural criticism’ wrestles with and hasn’t yet managed to resolve satisfactorily.

I think you put that very compellingly. It’s difficult today to point to anyone whose work provides a persuasive example of a social debate, who might not provide the definitive answer but does point us toward a direction we hadn’t really considered; a figure who is consequently of sufficient interest to the popular press to rate an interview or roundtable conversation that the professional debate can start mulling over.

Equally difficult is how to transition from criticizing to affirming the status quo.

Some people have completely lost faith in Rem, with his endless laments about the ubiquity of the market and the absence of a public client. I find it rather amusing that, after his reputation as a radical ‘realist’, he has arrived at a quasi-Marxist position, while he himself can’t complain about a lack of fame and attention. But as an analysis, it’s not bad.

If I were to raise an even broader theme it would be about the disappearance of authority. It’s fairly fundamental to how society deals with information, acceptance, control. The effects can be seen in a great many areas, including architectural criticism. And in that context, I’m curious to hear about your study of a number of great architectural critics. What were you looking for? And what did you find?

Maybe an escape from the debate about the future. I’ve bid farewell to a lot of magazines. What I could still say something about is that in the past I’ve seen moments when authority did exist, that became the subject of mythologizing, such as Giedion and Pevsner, who are mentioned in the same breath, even though we didn’t investigate how that came about. And how that authority was built up and what sort of readership those people had. Was it made up of the general, culturally-minded public? Or were they the people who were making architecture? Were they schools of thought? Was it the international CIAM, in the case of Giedion? All those people were consigned to history with an epitaph that suggests you’re better off keeping your distance. Alongside the hard print architecture magazines, with or without an accompanying website, you have the Dezeens and the blogs. Fifteen years ago I gave a lecture in which I committed to following the leading lights, but I don’t see any people coming to the fore in that world either. Any more than in the ‘little magazines’, of which they are the digital versions, but with the same limited readership. What’s lacking is polemic. Bob Somol still engaged in that; he said straight out: ‘this is wrong, that is right’.

That links back to our earlier remarks about authority. Architectural criticism lacks influencers to guide the opinions of the group. I can’t see any of that kind of structuring of opinion right now.

No, but nor do you see people wanting to know which Gehry is better. Is the Louis Vuitton Gehry better than the Bilbao Gehry? I think it is, but it would be a tough job to argue why. And maybe nobody cares.

That conversation has died out. But on the other hand, compared with other cultures, as Umberto Barbieri once pithily remarked, ‘unspoken is unheard’ in the Netherlands. In this country we have to talk explicitly about the worthwhile and the significant as well as the failures and disasters. In Italy, for example, if the architectural critics neglect to discuss a project or development, that is (or was?) perceived as an implicit criticism. In the Netherlands such an omission provokes at best an indifferent ‘missed that one’ or not even that. Which shows just how differently criticism can work in different cultures.

Well, it was a different story within the small circle of Archis editors. I recall when the NMB head office in Amsterdam-Zuidoost, designed by our theosophical friends Alberts & Van Huut, was completed in 1987. Because it was so extraordinary and big and unique there was a discussion as to whether we should feature it. Some wanted to ignore it altogether, but I didn’t agree. So I read up on that way of thinking and how it was promoted with ‘there are no right angles when you dance’. The building had three narratives. The first was for Bres, one of those esoteric magazines, including conversing with cauliflowers. The second was for the Town Planning department: the inflected elevations are all about reflecting traffic noise. And the third was aimed at the general public: you’re tired of slick and orthogonal? And they promptly won the Popular Choice Award organized by the local newspaper. So you have three narratives about an architectural practice firmly grounded in anthroposophy, of which the client was also an adherent.

I’d like to raise two other matters with which you were involved. The first is ‘the legitimacy of architecture’. Is that still a live issue today?

Legitimacy is about being acceptable, but also about being sanctioned, being approved. I increasingly encountered the term, including in Manfredo Tafuri, who wrote about the Roma Interrotta project in which Nolli’s map of Rome was divided into twelve sections, each of which was given to a different architect who was tasked with projecting their own design over it, to do something with it. Tafuri was furious and claimed that it destroyed any shred of architectural legitimacy (stronger than mere credibility). It was presented as a cultural protest, but what was it really about? That was the tenor of his article.

A concept like ‘legitimacy’ only makes sense if something is at stake.

Yes, you’re right. It’s a good question whether anything was at stake. So the issue is whether you repudiate every aspect that develops fairly autonomously or is talked about in the wider social maze in which that discipline has to operate. In that case you end up with something that exists only to carry out a program satisfactorily rather than something that transcends that, that you can talk about.

But if you leaf through the Archis volumes you come across things like the autonomy debate that make me wonder what we were getting so set up about? Some discussions can be carried through into the present day, but there are others that prompt me to think: okay, it was a long time ago, yet so much energy was invested in it, with books, exhibitions, debates, the lot. So, what was at stake?

There was a book that helped me a lot. It was That was the rich harvest of what we received from the 19th century. But it was a genuine architectural criticism issue: can you explain what is so important about architecture, over and above putting a roof over people’s heads or shaping communal life in the village or landscape? What is the big A? There’s a word for it, the architecturesque, that I once came across in a book that had a strong impact on me early in my studies: Peter Collins, Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture, 1750-1950 (1967). All those discussions about so-called modern architecture, all those theoretical positions, they’d already been articulated in the 19th century. We were just rehashing them. That book set me firmly on a relativizing track with the result that the whole for or against modernism debate and that fundamentalism started to pall. It made me curious about new things and their accompanying narratives.

What do you think is your most influential article to date?

Oh, that’s a difficult one. I always found it easier to write about Herman Hertzberger than about Aldo van Eyck because Hertzberger was so amenable to analysis. But I never did dare to write: he acts as though he’s making all those people in that office building [Centraal Beheer] happy, but I don’t believe it for a moment. He’s the greatest formalist in Dutch architecture. But still, I enjoyed doing that, analyzing. The same is true of Stirling’s museum in Stuttgart. Is it wrong, or not so bad, does it contain layers that we previously ignored; I got a kick out of that.

Architectural criticism, at the level we are talking about here, is like throwing a stone into a pond then looking to see what ripples appear. But all too often nothing happens, nothing at all.

Perhaps we’re in just such a period now. Sylvia Lavin has described this malaise in her article ‘Lying Fallow’ (Log 29, 2007). The land may recover, maybe something is afoot that we can’t see yet. Peter E. of New York has been preoccupied with the theme ‘lateness’, preparing for what is coming without actually being able to see it yourself. That’s a narrative to grow happily old with. But you have to admit that there are periods when things speed up and others when it’s a bit subdued.

But nonetheless: sometimes you do something and you discover, possibly to your surprise, that it really catches on and is picked up. I think your piece about ‘schoolmasters’ modernism’ had a dual function. Your presentation of the world was very clear, and it also had a liberating effect. It finally created a space for postmodernism, a space that had not existed in the Netherlands. I thought that was a very interesting intervention.

And the good thing was that I couldn’t be claimed by either party. That is indeed an article that had an effect. And my essay in the Yearbook about the legitimacy of architecture, where I distinguished three types of legitimacy. I commend it to the reader!

I do not believe in an all-dominant Zeitgeist that you can blame for everything, but I do believe that in every age there is a kind of modulation of a number of more enduring dilemmas. The art is to rearrange paralyzing polarities in such a way that the narrative can move forward, and that curiosity is piqued.

Hans van Dijk, ‘De woorden en de werken’. In: Dikkie Scipio, Simon Franke (eds.), Bouwmeesters. Het podium aan een generatie, Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers, 2007, pp. 10-22.