Can architecture bring positive elements in peacekeeping operations? Does it have a substantial role in the transition between ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ peace?

Arjen Oosterman’s opening questions set the tone to the varied contributions enriching the debate on Architecture of Peace during the Law & Order Mini-Conference, taking place at Stroom The Hague on May 20th.

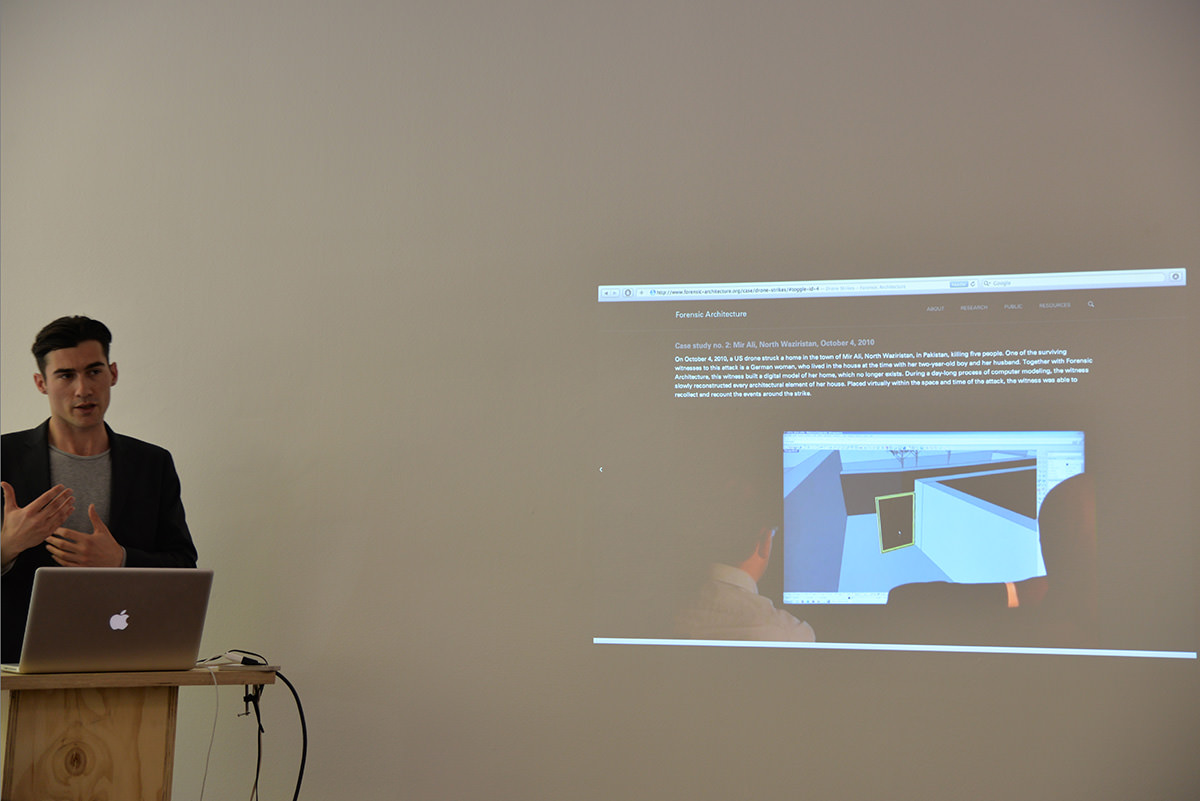

Francesco Sebregondi presented the multidisciplinary Forensic Architecture Research group hosted by Goldsmith University in London, describing how he and others in the team have redefined and expanded the meaning of the term ‘forensic architecture’ — originally referring to the work of building surveyors — as the assessment of spatial evidence for its presentation in legal and political setting.

Buildings aren’t static but dynamic, and due to their constant transformation they are the starting point of an investigation that is both a spatial analysis and a critical practice. Architecture is a registration machine of the environment that surrounds it and by reading the existing buildings, or even the ruins, it is possible to reconstruct narratives and events through the matter that has registered them.

Forensic Architecture is a citizen-driven re-appropriation of the means of production of the public truth that is currently being produced through state-controlled forensics. In this sense it represents a political practice and a form of activism.

Illustrating ‘Drone strikes’, one of the cases examined by the research group, Sebregondi showed how the combination of witness declarations and technology – as satellite imagery and 3D virtual modeling – leads to a reconstruction that produces evidence of a strike and may help other investigators working on drone warfare, as those involved in legal processes. The case demonstrates how through the use of cross-referencing sources, even in a situation of data scarcity, it is possible to produce a convincing account of what happened.

‘White Phosphorus’ is another research that deals with the idea of an Architecture of Peace, focusing on the use and effects of white phosphorus munitions in urban environments, the Gaza strip in particular. Through this research they were able to help stop the Israeli army to use this weapon. Thus, the actual production and provision of knowledge can be a tool to stimulate new ways of thinking and contribute to peace.

If Sebregondi and the Forensic architecture group focused primarily on how spatial knowledge can help stop conflict and injustice, Eamon Aloyo started from the other perspective in his presentation: conflict prevention. As political scientist and senior researcher at The Hague Institute for Global Justice, he gave an overview of the institution he represented – which works at the critical intersection of peace, security and justice – through the illustration of the Conflict Prevention Program. Its objectives are the improvement of conflict prevention and the mitigation of injustices resulting from conflict by producing knowledge.

Between the Institute’s strategic themes, ‘Frameworks, Principles and Norms’ is the one Aloyo is primarily working on. A description of his ongoing original research clarified the framework in which the organization operates: ‘The Last of Last Resort’ is a paper about intervention in conflict and addresses the issue whether it could be justified or not. It is common sense that war is terrible and violence should be used only as a last resort, when other options – as diplomacy and economic sanctions – have been tried and exhausted. Aloyo stated that although this intuition is good, the last resort should be considered as one of the options and measured by its effect. The account “War is only permissible if you have tried all other options”, according to him, is problematic and should be reformulated as “War is only permissible if you have exhausted other options that have a reasonable chance of success”. It doesn’t matter if the intervention is violent or non-violent, what matters is who is harmed (whether they are innocent or non-innocent people) and that the attempt consists in minimizing the harms, even if it doesn’t obligatory cancel the need for war.

Another paper, ‘Responsibility to Prevent Principles: From Just War Theory to Just Conflict Prevention Theory’ is about R2P (Responsibility to Protect) and prevention and explains how, according to the author, war theory precepts can and should be applied to conflict prevention.

Aloyo’s report pushed the debate towards the theme of prediction: how is it possible to balance intervention or non-intervention, or different kind of interventions, knowingly saying which is going to have the least or worst impact? The speaker believed that the use of the best evidence available should be encouraged, knowing that it is imperfect but that it suggests what it is likely to happen. Francesco Sebregondi still wondered if it is risky to assume that statistics have the capacity to grasp a multiplicity of scenarios: the effects of war perhaps cannot be reduced to a probabilistic calculus of the actual victims. And this characterized the two positions of Sebregondi and Aloyo as pragmatist versus idealist, as subjective versus objective; two different worlds, really in which the political is either a reality or an ideal.

The third keynote lecture was given by Mark Kersten, researcher at the London School of Economics, specializing in conflict and peace studies and international criminal justice, and founder of the ‘Justice in Conflict’ blog.

He traced the history of the International Court of Justice, from the Nuremberg trial on, when there was no consensus of what or how much justice was required, and analyzes the Latin American case of Argentina where initial immunity for all leaders of the Videla regime was abolished in the end to allow prosecution decades after the facts. In general he asked for some patience in assessing ICC’s effects and results (international justice is a very young discipline and still in the making), and warned that ‘our’ appreciation of its function and effects should be realistic (it cannot bring peace), but also called the ICC to be self-critical and aware that serving ‘the good cause’ can easily contribute to conflict, paraphrasing the motto of Volume 26: “To know how justice contributes to peace we need to understand how it contributes to conflict”.

After the partisan, the objective and the relativist position, Jan Willem Petersen presented ‘facts on the ground’ of peacekeeping reconstruction. As strategic spatial planner, architect and researcher, he is the founder of Specialist Operations, an independent spatial strategy and design consultancy that operates in conflict-affected environments. He presented the post-conflict and reconstruction situation in Afghanistan, more specifically the positions in these processes of the different contributing nations. He wondered what encompasses nation-building, affirming that it is always a military-led endeavor.

According to Petersen, when we talk about reconstruction, we shouldn’t evaluate success in quantitative terms: instead of asking how many buildings and projects have been completed, it is more useful to look at the quality of those projects, asking how many problems have been solved. This in response to one of the findings of his research, namely that the military involved in peace building and reconstruction, use other criteria to measure success than civil organizations would. Another outcome cum recommendation of his research was the realization that architects and urban planners often are not involved in the military lead reconstruction or during the temporary military occupation.

The symposium brought a mix of practical tools, theoretical notions and facts on the ground that contributed to the understanding of what ‘architecture of peace’ includes. It didn’t fully answer the questions asked at the start, but that would have been too much to ask. It did provide a richer understanding of aspects included, but also that to answer the question: ‘can architecture help materialize peace?’ affirmatively more research and evidence is needed.