As an introduction to our next issue Volume #54: On Biennials, we are glad to feature In Statu Quo: Structures of Negotiation; this article is based on the eponymous book of the curators Ifat Finkelman, Deborah Pinto Fdeda, Oren Sagiv, and Tania Coen-Uzzielli, whose topic Status quo was the theme of the Israeli Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia.

In ‘The Crisis of the Secular’, the historian and journalist Ofri Ilany describes his impressions after a visit to the Haram al-Sharif:

And then I returned to Tel Aviv. The return from Jerusalem to the coast is a gradual motion of forgetting the Temple Mount. It disappears first from view and then from consciousness. Everything that was crystal clear when standing and gazing directly at the dome becomes obfuscated, distant. Things take on a different, secular meaning, transforming back to their rightful place and color, like coming down from an acid trip. Life in this country seems to revolve again around material stuff – consumerism, career, real estate. It goes back to feeling like everything here has a price. But this is a mistake. The Temple Mount is a priceless forty acres.1

Since the 1920s the issue of holy places in Palestine – and particularly in Jerusalem – has been employed by nationalist politicians to symbolize the Arab-Jewish conflict. The growing clashes between rivals demanding sovereignty over one piece or another of consecrated territory have turned these monuments into ticking bombs, which alternate between moments of calm and eruptions of violence.

As seculars we tend to turn our backs on holy places. As far as we are concerned, they are “a nuisance buzzing on the news that we must endure”.2 As architects we stand mute in front of these monuments, which elicit enormous emotion and inspire endless political maneuvers. Their monumentality is evident, and yet we struggle to treat them as architecture in the present tense, to understand their relevance to our current discourse and debates.

What then is the role of architecture in places of such controversy? In the words of the historian of architecture Alona Nitzan-Shiftan, “We must seek the answer in the here and now; […] in the day-by-day reality that unfolds in very particular ways within these impossibly complex landscapes. […] While the historical and religious narratives of these sites are served by an architecture […] of power and determination, the capacity to operate these monuments and allow for the daily coexistence of numerous groups, requires a different articulation of architecture, a gray-zone architecture of negotiation.”3

A Clockwork Condition

In the 21st century religion has once again become central to the identities of many local and global communities and is at the heart of numerous conflicts. In the geopolitical context of the Holy Land, the cradle of the three monotheistic religions, the combination of historical events, myths, and traditions has fostered the creation of a multiplicity of places that are sacred to competing religions, communities, and affiliations. Because of their supreme importance, many of these places have become arenas of bitter struggle over both territory and worship rights, yet they continue to coexist through the essential system of regulatory codes known as the Status Quo.4

Initiated by the Ottomans in the mid-nineteenth century and later advanced under the British Mandate, by the United Nations General Assembly in 1947, and by the Israeli Holy Places Law in 1967, the Status Quo requires whoever is in power to maintain a delicate web of negotiations and agreements that allow contested sites to operate in their daily routines. In a wider context the Status Quo is a modern order imposed (by consent or coercion) on the inevitable “religious madness”.5 It exemplifies what the architect and historian Daniel Bertrand Monk, writing about the Israel-Palestine conflict in general, has called “the dramaturgical organization of political experience”, which is confirmed in the “small catastrophes of everyday life.”6 It also recalls Anthony Burgess’s explanation of the title of his novel A Clockwork Orange (1962): “the forced marriage of an organism to a mechanism, of a thing living, growing, sweet, juicy, to a cold dead artifact.”7 In a similar fashion the Status Quo principle demonstrates the clash between the organic and the artificial. It provides secular and rational mechanisms of control and management within the sacred place, which by definition is a non-rational, sublime, and uncontrollable domain.

Dividing the Indivisible: Complexity and Contradiction in the Holy Places

A more fundamental contradiction that arises from the encounter between holy places and the Status Quo that governs them is the incongruity between the idea of the ‘holy place’ and the notion of sharing it. According to the political scientist Ron Hassner, “sacred places are coherent monolithic spaces that cannot be subdivided, they have clearly defined and inflexible boundaries, and they are unique sites for which no material or spiritual substitute is available.”8 Hassner’s argument regarding the ‘indivisibility’ of holy places maintains that because disputes about sacred space involve religious ideals, divine presence, and absolute and transcendent values, there is no possibility for compromise. Thus tombs, temples, churches, mosques, and shrines “may contain numerous stations, subdivisions or areas with varying degrees of sanctity relative to the ‘center’ of the sacred space, but the components are always integrated by means of ritual, symbol and law to form a coherent whole. […] The total structure cannot be […] separated into subcomponents or parceled out without being deprived of its sacred function.”9 This demonstrates how crucial the indivisibility of holy places is in negotiations of their potential partition. Moreover, it suggests the complexity and even fragility that lie within the idea of the Status Quo as a conflict resolution apparatus as well as the challenge inherent in the architecture that responds to those conflicts.

The Status Quo is after all a documentation of political struggles, power positions, and hierarchy between rivals at a given time. And while it helps to prevent violence and maintain established customs, it also spurs the contending parties (especially the ones discriminated against) to continue their struggle for rights and possession. As such, it is no more than a temporary solution, valid until the next violation of the hegemony leads to the definition of a new one.

Practices of Sharing the Sacred

A contemporary reading of this complex, multifaceted, and dynamic realm presents both challenges and great opportunities. Looked at within an architectural context, the Status Quo reveals the spatial and temporal strategies through which sacred places in conflict manage to retain their modus vivendi. Three major contested holy sites – all located along the Jerusalem-Hebron axis10 – exemplify this phenomenon. Within each of them architecture serves as a significant agent to mark spatial negotiation and to suggest a possible, if controversial, performance of sharing the sacred. The discourses and practices associated with these holy places are characterized by distinctive networks of objects, images, gestures, and meanings that have realigned political and cultural relations.

Protocols of Space and Time

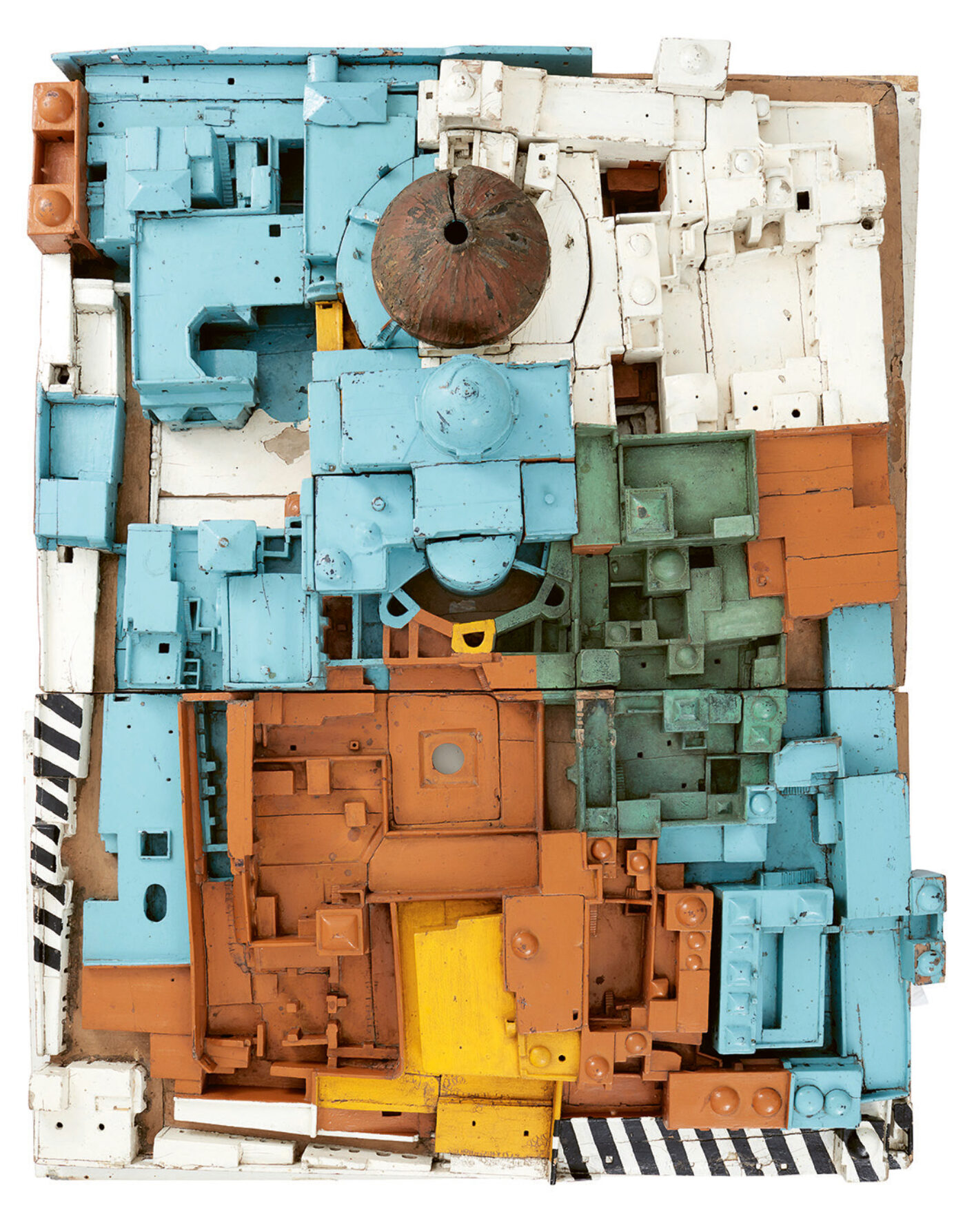

In 1862 Süreyya Pasha, the Turkish governor of Jerusalem, commissioned Conrad Schick, a German Protestant archaeologist and clockmaker, to make a model of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.11 He believed that only a three-dimensional representation of the church could clarify its elaborate ownership arrangements to his superiors in Constantinople. This was essential after the Crimean War (1853–56), which had been sparked by disputes over the rights of Christian minorities at holy places in the Ottoman Empire.

Inscribed on the wooden model are two hundred numbers that refer to specific elements of the building, while different colors indicate their affiliations with the various communities. The model turned out to be an object of interest for several world leaders, and copies were made for the Greek Orthodox patriarchate, the king of the German state of Württemberg, and Queen Victoria. Made with movable parts, it served as a key instrument, not only illustrating the complex state of affairs in the church but also pointing out possibilities to those who would formulate the Status Quo system.

The spatial configurations established by the Status Quo more than a century ago still regulate the daily routines of the denominations that share the church: Greek Orthodox, Latin, Armenian, Coptic, Syrian, and Ethiopian. These arrangements divide the structure into minute segments and subsegments with clearly delineated areas of responsibility. Yet even this is not sufficient without a meticulous schedule of daily activities, religious or mundane, implemented throughout the site, including areas common to all sects. Whether the celebration of a mass, maintenance and restoration work, access arrangements, or cleaning rights, it is the ceremony, the performed event, that completes the precise division of the site. These space-and-time protocols articulate the tense choreography of division and sharing.

The case of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre addresses one of the most crucial elements that sustains the Status Quo: the ritual. As suggested by Pier Vittorio Aureli, the prescription of the sacred becomes explicit in collective religious acts: “Within rituals, gestures become a form of knowledge based on the congruity between notion and motion, between logos and praxis. […] Through their re-enactment, rituals not only transmit religious content but also generate a collective consciousness and memory that is immediately spatial. […] As such, rituals give form not only to shared space, but to shared time as well.”12

An Ongoing Project

In practice, even if its name may suggest otherwise, the Status Quo system is dynamic, responding to changing circumstances and enabling continual negotiation between various stakeholders in a given holy site. A clear example of such a negotiation is the series of architectural proposals for the Western Wall Plaza, another site of intrareligious rivalry.

Shortly after Israel gained control of the Old City of Jerusalem in June 1967, during the Six-Day War, the Mughrabi Quarter – an eight-hundred-year-old Muslim neighborhood adjacent to the Western Wall – was demolished.13 Thus the Western Wall area, an intimate courtyard only four meters wide, suddenly became a vast plaza, a tabula rasa open for interpretation and definition.

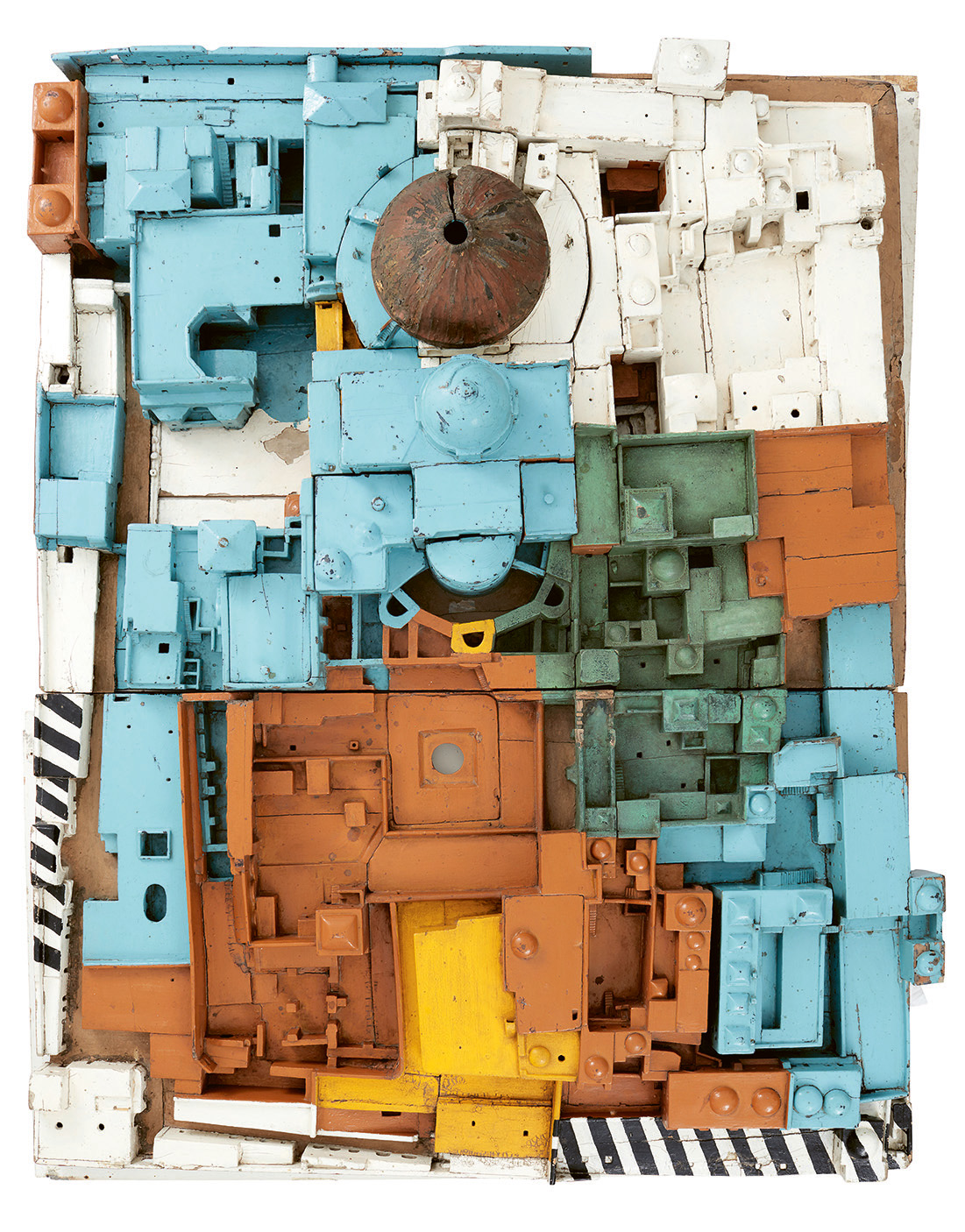

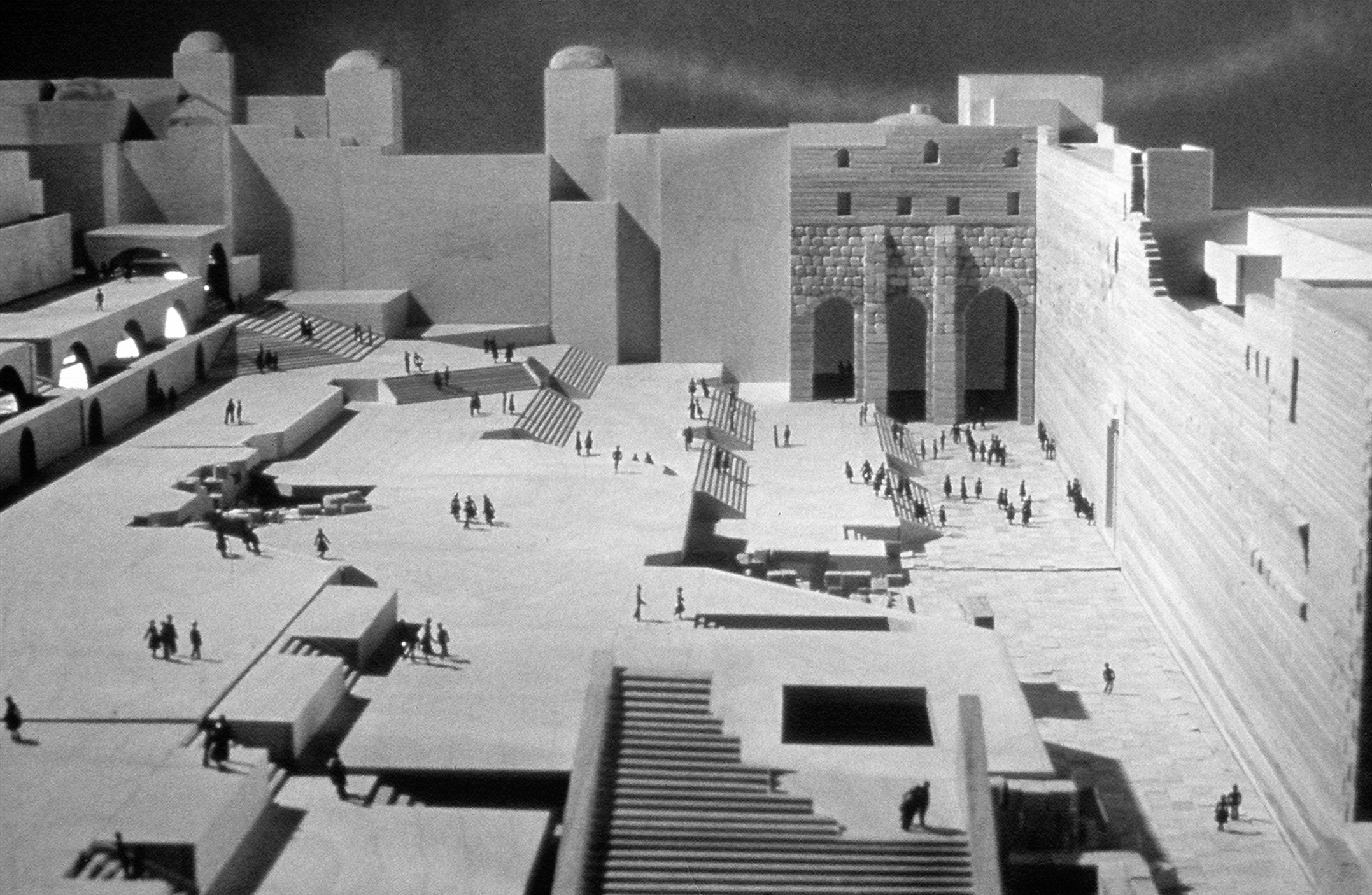

Since that summer many architects and entrepreneurs have sought to leave a mark on the site. Among the designs submitted for the plaza and nearby areas are some from well-known international figures: Louis Kahn’s symbolic concept of a pilgrimage route (1967), Isamu Noguchi’s monumental and sculptural landscape design (1970), Moshe Safdie’s huge hierarchical theater of descending cubes based on prefabricated elements (1974–85), an alternative grid-based scheme offered by Adolfo Natalini and David Palterer of Superstudio group (1980–82), and Michael Arad’s creative solution for an egalitarian prayer area for all non-Orthodox groups (2014). The different proposals reflect two distinct yet closely connected conflicts: one over the balance between Judaism and statehood in a transforming Israeli society and another over the religious hegemony between different Jewish streams in Israel and the Diaspora.

Ultimately none of these proposals were implemented. The inability to agree on a definitive design for the plaza reflects the polemic over the character of the Western Wall as a holy place and a national symbol but also a broader struggle over the identity of the post-1967 Israeli state. Thus, the current arrangement of the Western Wall Plaza – a spatial consequence of events that took place more than fifty years ago – illustrates how “indecisiveness in the face of a complex issue allowed the preliminary and temporary design to remain intact, as a last resort in the attempt to find a permanent solution.”14

Object Politics

The charged status of ‘temporariness’ in contested holy sites is itself a product of the overall territorial conflict. It embodies what Monk calls the “political immediacy” of architecture.15 As such it is manifested as an ad hoc or matter-of-fact spatial condition that, even if it seems crude and unimportant, has become monumental and significant far beyond its functional scope. In this regard the Status Quo in the Cave of the Patriarchs – a place in which the interreligious conflict implies the presence of historical and political powers in the shaping of space – introduces an alternative for notions of both temporariness and object politics.

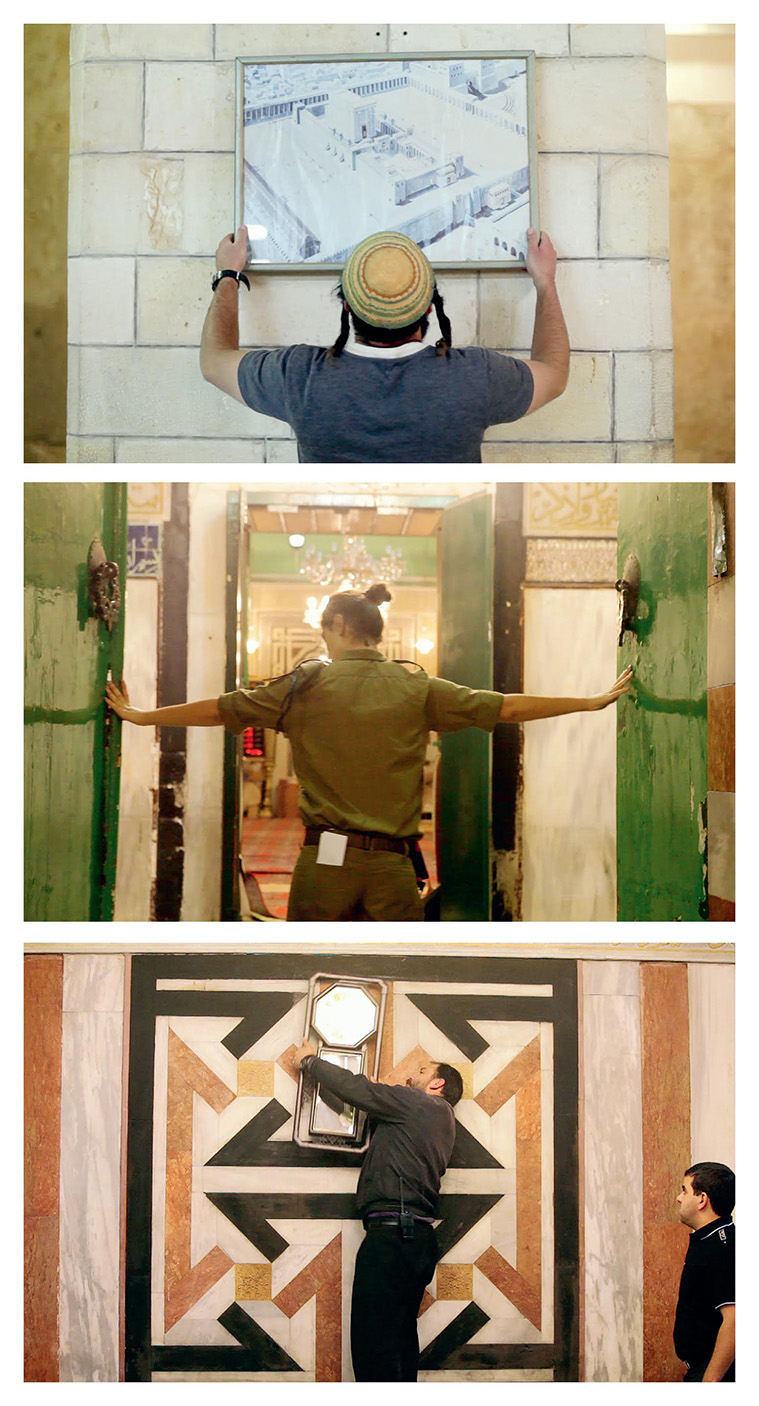

The cave, also known as the Ibrahimi Mosque, is a monumental Herodian building in the old city of Hebron (Al-Khalil), a holy place for both Muslims and Jews.16 For more than twenty years, under the formal sovereignty of the Islamic Waqf, controlled and maintained by the Israeli authorities, the shrine has been divided for separate use by both religions according to a strict set of protocols.17 Jews have access only to its southern halls, while Muslims are restricted to its northern part. For twenty days each year known as ‘exceptions’, however, on the occasion of important Jewish and Muslim holy days and under close military inspection, the site changes hands for twenty-four hours, enabling each side to have full use of the cave. In a matter of hours the Jewish or Muslim chambers are cleared of all artifacts and stand vacant for a few moments before their temporary occupants bring in their own objects and turn the emptied rooms into a mosque or a synagogue.

The temporary evacuations of the cave are the product of a forced and regulated Status Quo that ensures religious coexistence. In these swift and carefully choreographed transformations, simple objects such as plastic chairs and carpets are used, just like the elements of a stage set, as ideological agents to define a momentary identity for this ancient monolithic container. Thus, the sensitive question of land appropriation in the name of religion is analyzed by means of artifacts and repeated gestures performed to demarcate a territory.

The Cave of the Patriarchs, Hebron / Al-Khalil.

Courtesy of the artist

Architecture of the Meantime

The investigation of contested holy sites, beyond its relevance at any given time in history, reveals programmatic spatial phenomena that suggest alternatives to the antagonism within such places. Relevant to this study is Monk’s notion that “architecture […] presents itself as a cipher of history. […] Architecture itself assembles and reassembles the constellation of possible positions actually assumed by participants in this conflict.”18

This type of observation demands that we pay full attention to the processes, decisions, and actions through which monumental sites are shaped. It considers not only the instrumental use of architecture to lay claims in conflicts but also its capacity to negotiate between different identities in space. More important, it allows one to look at architectural phenomena beyond pragmatism, methods, order, form, material, and style, beyond the immutable and perpetual medium it usually stands for. Within the practices of places thousands of years old, it adheres to another concept that embodies constant change: the architecture of the meantime.

–

*This article is based on our book In Statu Quo: Structures of Negotiation (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), published in conjunction with the Israeli Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018.