Fight and Accept

When the credit crisis struck, the general response was one of sheer amazement. Fascinating to see billions and trillions of dollars evaporate at such speed. Despite experts´ warnings that things would never be the same, expectation in general was that normality would be restored soon. In our spectacle society we are used to the excitement of sudden change. We respond to these events like we’re watching a magician. First he shows that everything you see is ordinary, everyday, no tricks involved. Next he stuns his audience with the unimaginable and while the public is still struggling with excitement and deeply felt anxiety , he restores the order of normality – look, nothing has changed. This is the understanding of reality we prefer: nice show, lights on, back to business.

There is another model of reality active in our understanding of our own situation, the managerial one. A problem arises, regional population shrinkage, sea level rise, that sort of thing. It has to be addressed and solved, someone has to do it, but it’s not my concern. Cannot the government or the municipality take this on? I pay my taxes, don’t I? It’s beyond my reach anyway.

In a peculiar way, both models make for a nice, stable world, at least on a personal level. They are two cornerstones of the bourgeois belief system that keeps things going. Tomorrow won’t be that different from today. Like minor ailments, disruptions (even major ones) will spontaneously go away or can be treated. But what about aging? As one of the essences of living it’s been always part of life. No denying, no escape. But on the scale of society, major changes are happening. The doubling of our life expectancy within a century’s time, the dramatic increase of the 65plus part of the population compared with the population as a whole (and this is not just happening in the West). It challenges our own expectations and obligations, as it threatens social models we’d grown accustomed to. So where is the magician and where is the manager?

Well, the magician is at the doorstep. S/he’s called doctor and biomedical research. The trick ‘now you’re young – now your old (scary!) – now you’re young again’ is currently mainly one of appearance, but a more fundamental meddling with the body system is looming at the horizon. Instead of replacing defunct body parts in a mechanical way (the doctor as mechanic, the body as machine) other approaches are being tested. Growing tissue and eventually complete organs is one. Another is switching off the aging mechanisms in cells on a genetic level (renewal systems). A third one, that promises results within the decade, focuses on preventing damage on cell level. The random assaults in our biochemical body produce deterioration and failure of functions in time. By elimination of these assaults (free radicals) the body can continue to perform properly at old age. If not the recipe for eternal life, a serious extension of one’s healthy lifespan is the least to be expected. Basically, these developments focus on the elimination of aging as phenomenon. After the agricultural and the industrial revolution, fighting aging promises to be the next revolution in the making.

The social and spatial implications of these developments are hard to imagine, but before this becomes reality there is some time for reflection. In the meantime we’re in the middle of the earlier mentioned transformative shifts and it is here that the manager appears on the stage. After the second world war the west turned to building the welfare state: a lifelong guaranteed material minimum for everybody. It came with retirement, state pension and taxes of course. The model was based (and still is) on solidarity of the younger generation with the older one. The working population pays for its parents’ and grand-parents’ care. Not unlike in traditional societies, where the children take care of their older family members, but now on the level of society as a whole. This social arrangement came with a price: the working part of the population should not be held back in any way to contribute to production. So retirement homes, nursing homes etc were invented to free the core family from care obligations. Economizing labor under the guise of retained independence (parents not moving in with their adult children) was the model, alienation and segregation of a part of the population the result. Old age as a problem, a social burden really, to be managed and solved (from the production point of view). In the Netherlands and surrounding countries the (financial) limits of this arrangement became apparent when during the 60s and 70s the number of retirement homes (and costs) grew explosively. Mid 80s a drastic change in policy was set in motion. Instead of providing a room for every citizen of 65 and older, the policy was now (and still is) focused on keeping people away from institutions and in their own homes as long as possible. A whole set of intermediary care facilities and typologies were introduced. Next target was retirement itself. The analytical model of learning phase, working phase and retirement phase in modern society had to be replaced by a more continuous and inclusive model. Reconnection of the older population with production (where possible) and reintegration in society at large. Acceptance is the buzzword here. We’re in the middle of that transition.

It comes with all kinds of transformations. Instead of the ‘house career’, moving from one to the next home, depending on one’s personal situation (alone, family, empty nester, retired, care dependant), the emphasis shifts to environments that allow for all of these realities consecutively. It is another take on sustainability from a social point of view. Since buildings do not tend to expand or shrink, this asks for other types of flexibility. Same for cities, where shifts in population composition (age groups and income classes) change the economic and social realities.

Another challenge is the care for the rapidly growing number of elderly with dementia or multiple physical impairments and handicaps. The nursing home is the available institution now, but this hospital like end station is the horror scenario for everyone still at his or her wits. It is fascinating that an assignment that deals with total control has received so little attention from architects. Improvements within the walls of the institution are very well possible, but maybe we should design a whole new architecture of care for this category in society as long as the magician hasn’t perfected his trick.

The reintegration of old and young is not confined to health and physical performance only. A more integral look at society is gradually surfacing. Preservation has changed from a dedicated zone of expertise, dealing with rare species, into an integral take on what we have and what we need. In fashion and design, a less one dimensional and dogmatic focus on ‘forever young’ is discernable; the growing market of elderly consumers asks for adjusted marketing strategies too. After the age of ‘the new’, an era of integration may be at hand. An age more receptive of the faculties each individual has to offer at each phase.

With the major shifts as indicated comes a changing position and role of design and architecture. The realm of invention is still available and needed, but also and quite urgently reconsideration of ambitions and goals. The modernist dogma was provision of material quantity; the postmodern mantra was the provision of individualized style and quality. The challenge is to include value(s) in indesign. To start with Aging.

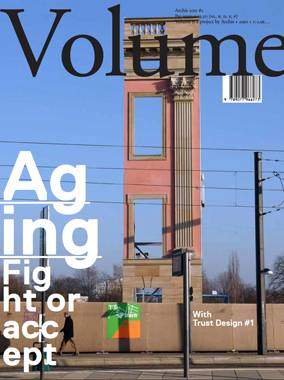

This editorial is part of Volume #27, ‘Aging’.

This editorial is part of Volume #27, ‘Aging’.

[button]Buy Now[/button]