Design New Futures!

Design New Futures!

Michael Shamiyeh

How do architects retake ground, how do they develop a new method? Shamiyeh addresses these questions in detail, explaining a practice of searching for emergent opportunities by relating science theory to business and management structures. He argues that creative decision making and problem solving are fields in which architectural knowledge is more needed than ever before.

To think about the architectural profession’s relevance today seems obvious, if not necessary. The question at stake is simple although finding an adequate answer is not a modest one: what can we do to get things moving in the right direction, towards professional renewal and raising practitioners’ ambitions, a process which is irrevocably linked to the development of self-criticism and even the danger of failure?

It looks as if liberation from the comfortable, risk-free dream-world of social acceptance we currently enjoy is indispensable. Yet for architecture to reacquire legitimacy we must rethink the potentials of the profession’s skills and techniques, to justify architecture as a form of knowledge and to seek possible clients. Thus what is called for, first and foremost, is an ambitious aspiration to reality, followed by concentration on the profession’s unique expertise. The question is therefore how to apply our own expertise more consciously.

The architect’s mode of operation, their way of thinking, harbors a strong and even unique potential among, of course, some other powerful competences. I am particularly referring here to the architect’s creative analytical approach toward problem solving and decision making that – were architects to utilize it to a greater extent than they heretofore have – would possibly allow them to become much more socially engaged today. The current enormous interest in the specific problem solving process at work in architecture by corporate executives and major business schools supports the proposition that there is something valuable in the architect’s approach. In order to make my point clear it is necessary to briefly recount the virtues of architectural design thinking in relation to strategic business thinking.

Decision Attitude

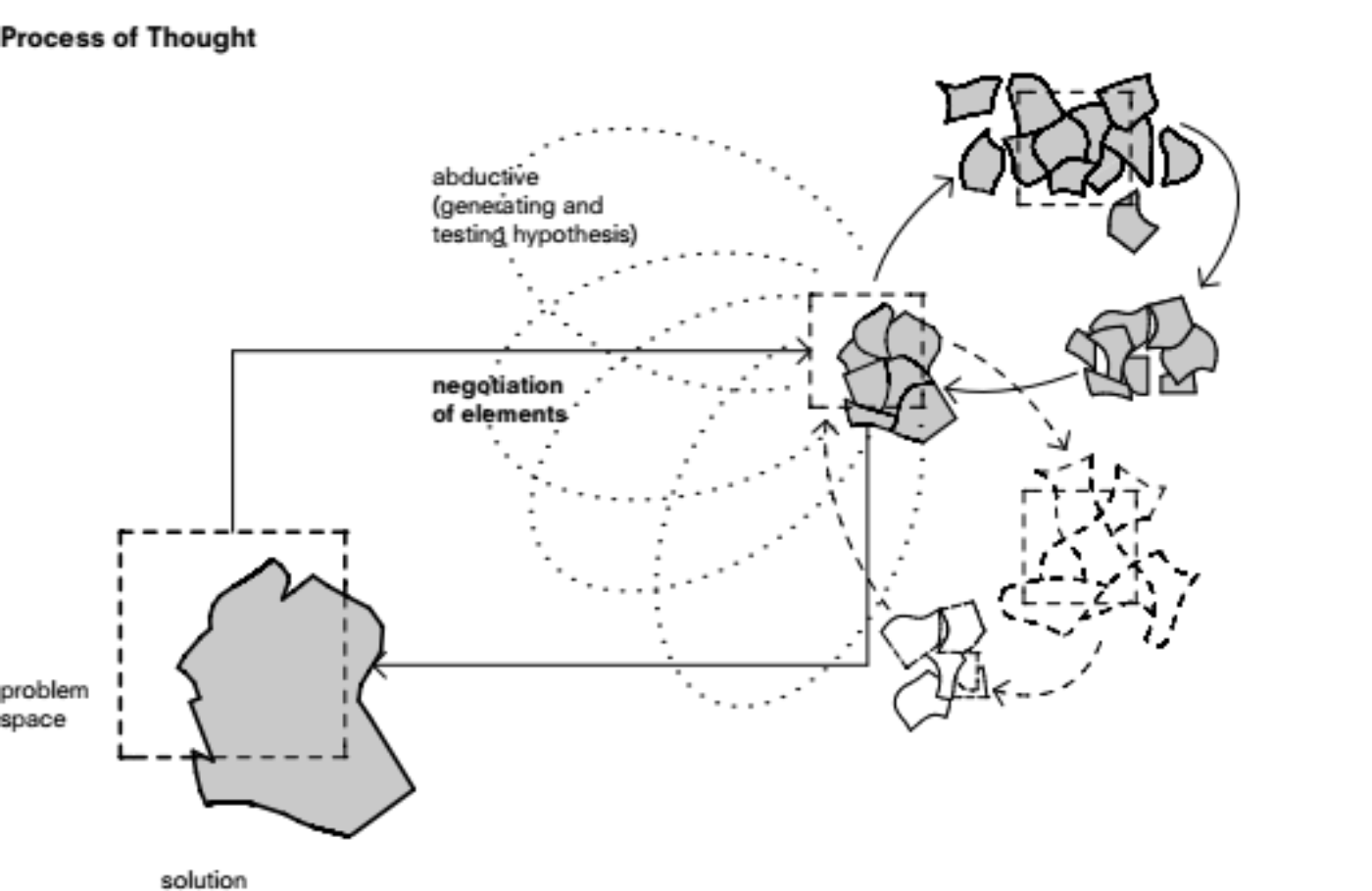

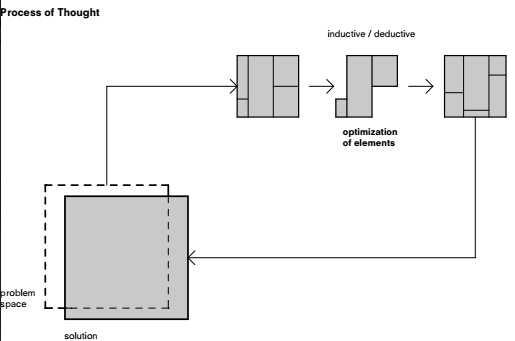

Taking a decision attitude toward problem solving is still overwhelming dominant in contemporary management practice and education. Such an approach solves problems by making rational choices among alternatives and uses ‘scientific’ tools such as economic analysis, risk assessment, simulation and the like. The decision maker, as a problem solver, assumes that the alternatives on the table, or the first ones they think of, include the best one which must then be perfected or optimized in relation to the prevailing or changing nature of an identified reality (see fig. 1). But for all the power of analytical approaches to problem solving, they share a central weakness in that they assume the alternative course of action the manager may choose. In other words, they start with the assumption that the alternative courses of action are at hand – that there is a good set of options already available, or at least readily obtainable.

Take the classical inventory control problem, for example. A decision attitude has traditionally modeled the inventory process as a buffer between varying demands placed on different sections on the production, distribution and consumption chain. That image became the default approach for several decades, while research and teaching inventory control worked to perfect – to ‘optimize’ – the model and enable the best possible decision making about time, quantity and location of inventory acquisitions. To question the very necessity of inventories per se was not up for discussion at all. Rather, the traditional image maintained the prevailing alternative from which to progress. At the dawn of the 21st century Wired guru Kevin Kelly praised smart techniques for more elegant and cost reductive management; this ‘default’ model carried within it its own form of closure. [1] For decades management was blind to possibility that inventories could be minimized or eliminated altogether by redefining the very problem itself; that is to say, by broadening the initial problem space to be able to rethink the overall organization of production processes, relations with suppliers, work force and information systems to finally discover the virtues of a lean manufacturing approach towards production. Think of Michael Dell’s computer corporation that revolutionized PC industry by becoming the first in the industry to sell custom-built computers directly to end-users, bypassing the dominant system of using computer resellers to sell mass-produced computers. This practice rendered inventory irrelevant. [2] In addition to being too susceptible to early closure of the problem space, another problem is rooted in the decision attitude – namely, that a decision does not generate ideas that give form to new opportunities, no matter how advanced the analytic capabilities of the decision maker are.

It is commonplace today to note that management as a profession is in a difficult situation. Men and women running businesses begin to understand that in the face of increasingly diverse complexities in our world – a world in which stake holders with different agendas and worldviews, organizations, economies and entire social systems are extremely interconnected and in which actions effect (or are effected by) others, often literally a world away – the very concept of ‘problem solving’ can be an impediment. Rather than initiating a larger process of creating what one truly values or wants, it suggests a way of thinking that proposes to fix something that is broken. It prevents someone from asking the more fundamental question: ‘what kind future do we want to create?’

The case of Cirque du Soleil, one of Canada’s largest cultural exports, strikingly reveals this operative limit of a decision attitude towards problem solving in times of emergent realities wherein solutions from the past no longer fit. As is well known, a circus is most commonly understood as a traveling company of performers that includes artists and trained animals. In a large tent with seating around its edge a series of acts are choreographed to music. Due to alternative forms of entertainment – ranging from various kinds of urban live entertainment to sporting events to home entertainment – the circus industry suffers from a steadily decreasing audience. Among many other new features, Cirque du Soleil did away with many traditional factors (e.g., the animals) and introduced elements completely foreign to the industry such as a theme and a story line allowing multiple productions and giving people (not just children) a reason to come to the circus more frequently.

The case of Cirque du Soleil exemplifies that something is missing in management practice, namely the capability to bring new ideas to the problem. In the last few years managers have come to understand that the failings of management are most directly attributable to a famine of good ideas. The problem is rooted in the very concept of ‘business administration,’ an activity whose emphasis remains on controlling, integrating and coordinating. While integration, coordination and control are all important tasks, a focus on these dramatically underestimates the value of and necessity to ‘design’ new futures in a time of change. Organizations must do both, resolve day-to-day problems and generate desired futures. There is nothing more elemental to leaders’ work than creation. [3] Significantly, there is a great difference between creating something one truly cares about compared to solving a problem, of making something one does not like go away. That is why management practice and education have begun to turn their attention to architects who do not wait for discovery (of some desired future state) passively but actively invent – ‘create’ – it and so primarily deal with what does not yet exist. They are, as Herbert Simon vividly reminded us, ‘concerned not with the necessary but with the contingent – not how things are but how they might be.’ [4]

In contrast to traditional managerial thinking, creative architectural thinking takes for granted that the process of finding a solution will require the invention – the creation – of new alternatives, given certain parameters and constrains. That is to say, whereas the decision attitude usually assumes that the alternatives at hand already include the best one, in architecture one is concerned with inventing the ‘best’ one. Thus whereas the first investigates extant forms to subsequently optimize and even perfect them, the latter is interested in initiating novel forms that fit the problem perfectly. Although architects are of course interested in investigating reality, they do so only to understand prevailing constraints and their underlying interdependences as much as they are influential to the process of creating desired futures.

Design New Futures

Beyond the difference in emphasis on existing or future conditions, there is something evident in the architectural approach towards solving problems that is perfectly designed to bring in new ideas. Rather than referring to the traditional reasoning modes of deduction or induction, the mode of reasoning involved in architectural thinking is essentially abductive. Charles Sanders Peirce re-introduced the (ancient) theory of abductive reasoning into scientific debate at the turn of the 20th century. [5] Whereas deductive reasoning applies general principles to reach specific conclusions, inductive reasoning examines specific information, perhaps many pieces of specific information, to derive a general principle. Deductive reasoning does not provide any new insight as the evidence provided must be a set about which everything is known before the conclusion can be drawn. Differently, inductive reasoning, where the conclusion is likely to follow due to a set of given evidence, does provide the ability to learn new things that are not obvious from the evidence, however, the gained insight is directly linked to – and as such determined by – the supporting premises of the argument.

Both types of reasoning are routinely employed in management practice and education. However, due to their ideal character both modes of reasoning are losing their relevance in the real world. This holds true particularly for deductive reasoning, as it is simply difficult to know everything before drawing a conclusion. This is where abductive reasoning steps in.

Abduction is a method of reasoning in which one chooses the hypothesis that would, if true, best explain the relevant evidence. [6] Therefore, ‘deduction proves that something must be; induction shows that something actually is operative; abduction merely suggests that something may be.’ [7] In other words, abductive reasoning starts from a set of accepted facts and infers to their most likely, or best, explanations. Thus while the other two modes of reasoning reveal a strictly sequential procedure for arriving at specific conclusions (two of three variables are known), abductive reasoning, in which just one of three variables is known, involves an assertion of causation, also known as an ‘if and then’ statement. For example, if a particular independent variable changes, then a certain dependent variable also changes. Significantly, in order to arrive at certain conclusions creativity is required precisely because the creation of a new hypothetical, invented and untested general rule maintains the starting point for any abduction. [8] For that reason Peirce argued that abduction is the only logical process that fosters one’s own initiative and thereby actually creates anything new. [9]

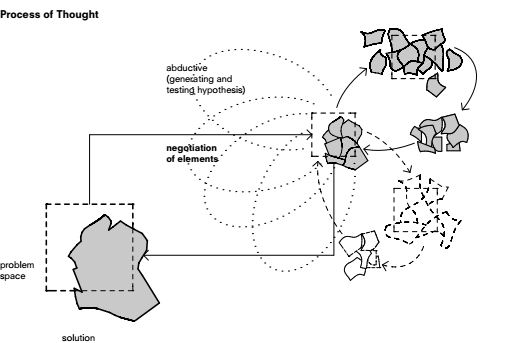

Unlike in business, in architectural design the emphasis on systematic procedures, the use of traditional reasoning modes of induction and deduction, as well as the application of prescribed techniques met with immediate criticism on account of the linearity of their processes and their lack of appreciation for the complexity of given (design) problems. (Refer, e.g., to debates in the 1970s). In reference to Karl Popper, Horst W. Rittel first called attention to what he described as the ‘wicked nature’ of problems architects are facing in their daily work. [10] Such problems, he asserted, are ill suited for linear techniques. Principles of the scientific method cannot be applied to them because wicked problems are characterized by a level of interconnectedness, by the presence of amplifying loops that produce unintended consequences when interfered with, by the presence of tradeoffs and conflicts among stakeholders, and by the nature of their constraints. Each formulation of the problem, of which there are many, corresponds to different – contestable – solutions. Consequently, when dealing with wicked problems one cannot first define the problem and then identify the solution. Solutions are generated all the time as problems are formulated. For this reason the architect adopts a creative-analytical problem solving strategy based on generating and testing potential solutions and is fundamentally concerned with learning and the search for emergent opportunities. In other words, architectural thinking internalizes a process that begins with a series of creative ‘what if’ hypotheses, continues by selecting the most promising of these for further inquiry and then takes the form of a more evaluative ‘if then’ sequence in which the logical implications of that particular hypothesis are more fully explored and tested. Although the scientific method of induction, with its emphasis on cycles of hypothesis and the acquisition of new information to arrive at new conclusions remains central in architectural thinking, the mode of reasoning is primarily abductive; that is to say, it is hypothesis-driven and uses the logic of conjecture. It conjures an image of a future reality that does not yet exist but may be real. This is the great virtue of the creative-analytical approach in architecture. It is a combination of creative imagination – an initiative that generates new ideas – and rational analysis, based on known constraints (see fig. 2). Take Rem Koolhaas’ competition proposal for the Jussieu Library as an example: as Jeff Kipnis points out, ‘in his project for the University Libraries at Jussieu, the architect […] generates a social setting organized less by the program than by the erotic fantasies of the voyeur.’ [11] The proposed ‘finite, fluid field of interactions’ introduces a theme absolutely foreign to the conventional brief of libraries. It is certainly impossible to arrive at such a proposal by applying reasoning modes such as deduction and induction.

In business complexity and constantly changing conditions are at the root of every problem. Confronted with such a situation, the very concept of problem solving appears misleading and the application of a step-by-step methodology to ‘fix’ problems unfeasible. Management too is faced with the ‘wicked’ nature of problems, to reiterate Rittel’s expression. The possibilities for problem definition and solution are equally unbounded and therefore good hypothesis generation is critical. The opportunities to solve these problems in a strictly sequential process are rare if not non-existent. Business – as well as many other professions – is thus in need of new ways to approach problems in order to create desired futures, conditions they truly want. For that reason strategic planning, whose very objective is to bring about the most favorable conditions, gains increasing importance in business today. Whereas traditional approaches to business assumed that planning creates value primarily through administration – that the power of planning is in the creation of a systematic approach to problem-solving – deconstructing a complex problem into sub-problems to be solved and later integrated back into a whole, the value of planning in a time of change and complexity cannot be underestimated. It is in this respect that the particular creative-analytical approach at work in architecture is of great value for contemporary managerial practice. Architectural thinking opens up a virtual learning laboratory in which a series of assumptions about a set of cause-effect relationships in today’s environment are generated and tested with the aim of creating a set of actions to transform a situation from its current reality to a desired future.

Hypothesis Generation

The brief discussion on the link between ‘revolutionary’ architectural and ‘evolutionary’ business thinking reveals that the architect’s approach towards solving complex problems and generating desired futures may be of great value for current management practice if not equally for others too, due to its incorporation of both creative/artistic and analytical/rational skills. In particular I referred to the role of hypothesis generation and testing and established the relevance of such an approach to business practice. There is certainly much more valuable potential to be discovered. Paradoxically, since time immemorial the architectural profession has been learning to translate recognized or conceived patterns of relationships (i.e., organizational interdependences or the diffusion of activities) just into a physical, spatial-material form. In other words, the profession’s most fundamental and longstanding values induce architects to react with a building – with concrete – instead of examining the extent to which these findings, or their approach to problems in general, would equally be feasible or useful in some other form for society. A glance at current daily affairs reveals that there is a great demand for people to internalize such a potential. However a step in such a direction would ultimately imply an ambitious liberation from our traditional disciplinary values. This is no modest step, but it would allow the architectural profession to expand its field of intervention extraordinarily.

References

1. Kevin Kelly, ‘New Rules for the New Economy’. In: 10 Radical Strategies for a Connected World, New York (Penguin Books) 1999, pp.14f.

2. Michael Dell, Catherine Fredman, Direct from Dell: Strategies that Revolutionized an Industry, 2006.

3. Peter Senge, ‘Creating Desired Futures in a Global Economy’. In Michael Shamiyeh (ed.), Organizing for Change. Integrating Architectural Thinking in Other Fields, Birkhaüser, 2006.

4. Herbert Simon, The Science of the Artificial, Cambridge (MIT Press) 1996, pp. xii and 111f.

5. Charles Sanders Pierce, Schriften zum Pragmatismus und Pragmatizismus, Frankfurt, 1991.

6. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce: CP 5.171.

7. Ibid.

8. Ludwig Nagl, Charles Sanders Pierce, Frankfurt am Main, 1992, p. 112.

9. Charles Sanders Pierce, Schriften zum Pragmatismus und Pragmatizismus, Frankfurt, 1991.

10. Horst W. J. Rittel, ‘On the Planning Crisis: System Analysis of the First and Second Generations’. In: Bedriftsøkonomen, No. 8, 1972, pp. 390-396.

11. Jeffrey Kipnis, ‘Recent Koolhaas’. In: El Croquis. No. 79, 1996, p. 29.

This article is part of Volume #14, ‘Unsolicited Architecture’.

This article is part of Volume #14, ‘Unsolicited Architecture’.