In the heart of the Camargue wetland region, not far from Marseille, lies Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer – a small tourist town perched where the Mediterranean meets the Rhône River known for its bullfights and roaming grey horses. The Camargue is more or less an island, barely connected with the mainland because of shifting wet boundaries that border the flatlands, swamps, lakes, and salt flats; the landscape opens itself up as a stark contrast when arriving from the mountainous terrains around Arles and Marseille. When I visited last winter, I was struck by the existence of various intricate rites of worship that intertwine the waters of the delta and the Mediterranean with the social customs of those who live within this ecosystem.

Camargue salt flats, photographed during visit. December 2024.

For more than a millennium, the inhabitants of the Camargue have honored their watery landscape through rites that renew their sense of kinship and hospitality to one another and to those who visit the region. In an era of omnipresent xenophobia, the ways (diasporic) communities express (ancestral) beliefs hold the potential to anchor life-affirming values: kinship, solidarity, joy, and care. Looking more closely, religious practices often reveal themselves as inherently syncretic, bridging cultures and ideas that contemporary borders and (ethno-)nationalism seek to divide. Water – both as a sacred figure and medium of worship – cleanses, nourishes, and ties life and death. Water is an ancestral connector to (once existing) seas, lakes, rivers, wells, and springs – sites of gathering and mystique. Yet in its transformative nature, it also marks places of departure and loss, contention and conflict, where borders are drawn, and land is divided along arbitrary lines.

Nearly everywhere in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, the Cross of Camargue is a noticeable feature – its design appears on building facades, tourist trinkets, and even the city’s flag: a trident atop a heart, forming an anchor. Decoding this intriguing symbol, intersecting aspects of the region’s history and water practices unfold, specific to its location along the sea and delta.

Postcard: Camargue. The Gardian’s cross. Horses in the Camargue marshes. House and Gardian’s cross, ca. 1904-1960. Reference 6 Fi 687 / Departmental Council 13 / Departmental Archives. All rights reserved.[1]

The trident represents the Gardians – the Camargue ‘cowboys’ who live in coexistence with the (semi-) wild horses of the wetlands, while the heart points to the Three Mary’s – Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, and Mary Salome. These three, according to legend,[2] were cast adrift from Palestine or Egypt and, after a treacherous journey, landed on this marshy coast. Welcomed by the local people, they settled in the Camargue, and in turn returned the favors, bestowing their charity upon the region. The Three Mary’s are now recurring holy figures along the French Mediterranean coast. Lesser known is the presence of Sarah, probably their black Egyptian servant, who is now venerated by the marginalized Catholic Romani as Saint Sarah.

The worship of the Three Mary’s and Saint Sarah is part of a longer tradition of syncretic worship existing in this region. These practices of veneration are a blend of various belief systems, of which Christianity is merely one current in this long stream of fused worship, where in the form of wells, springs, wetlands, and the Mediterranean Sea, bodies of water have a sustained importance in rituals and beliefs. For centuries, water stood for safety, cleansing, refuge, and wealth, even fertility and femininity, and hybrid rites of water-worship symbolized cycles of life, growth, decline, and death. The worship of the Three Mary’s and Saint Sarah, arriving by boat, continues this tradition of water-centered, syncretic spirituality that has adapted to unstable cultural and religious territory over these times. It’s a tapestry of legends and histories that may lend us interesting perspectives on our contemporary times, where exclusion and suffering along man-made borders and (religious) ethnostates reign. Along this coast, Eastern pantheons of Mithras, Ishtar, and Kali found resonance across continents and mixed with local pagan traditions of the Matres, and the Fates.

The ways ancient water practices live on in our day-to-day, gaining meaning and resonance through syncretism and collective tradition, shows that in a wider sense cultural hybridity and kinship have allowed humanity to survive and, in cases, thrive alongside one another. Even more so, modes of organization that respected water, land, and its inhabitants as equals, bound in body-and-soul, have remained integral to this wetland region even when oppressive, patriarchal systems were enforced first by the Roman Empire, and later when the post-Roman Merovingian church leaders attempted fairly late to Christianize the Camargue.[3] In observing the link between unruly terrains, dispersed and diasporic communities, and failing holds of empire over belief systems, I lean on David Graeber’s mention of “zones of cultural improvisation”, where the “absence of state power, […] the absence of any systematic mechanism of coercion to enforce decisions” results in “the emergence of what might be called democratic values.”[4] This is especially relevant in times when the ‘West’ still portrays itself the center of democracy while simultaneously treading on the values commonly understood as ‘democratic’: human rights, rule of law, liberty, justice, egalitarianism. Republican France is even credited as the birthplace of some of these values. Today, the ‘democratic’ West isn’t as welcoming as the Camargue region once was to the three Mary’s and Sarah the Black, escaping the Levant. Now, many refugees face the same choiceless journey from the continents of Africa and Asia, on their way to Europe – yet these crossings often end in tragedy.

The worship of the Three Mary’s and Saint Sarah in the Camargue region reflects a deep and enduring connection to water as a symbol of refuge, resilience, and coexistence. It serves as a parable for the evolving dynamics of coexistence in this landscape, revealing zones of (historical) cultural improvisation. Through four stances, I trace how water – both as a sacred element and a gathering place – shapes communal practices and embodies the intertwined histories of migration, faith, and survival in the wetlands.

I – Three Mothers

In the Provence region, several sites have been dedicated to the Three Mary’s, including Notre-Dame-de-la-Barque (Our Lady of the Raft), whose water-bound origins can be traced back to earlier pagan or polytheistic places of devotion. In this hilltop settlement, nowadays the center of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, the cult of goddess Artemis by Greek settlers was once prominent. The goddess of the wilds was seen as “a guiding spirit behind Phocaean immigration and colonization.”[5] It may be that the Greek settlers were daunted by the marshlands and vast delta, with its unknown challenges and inhabitants (the Gallic Avatici tribe)[6] and in such a way, in need of a guardian. The Gauls, in turn, worshipped these sites through land and water spirits. The most important of these were the Matres[7], the three Mothers. The Matres, of “various stages of womanhood”[8], or motherhood, are the earliest roots of Three Mary’s. Depicted with offerings and motifs of sacrifice, symbolizing earth and water (springs or wells), they were protectors against disease and bodily harm. At Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, both a spring and a well were found in the center of the settlement; the well currently is enclosed by a fence, with a sign indicating its historical origin.

Religious and cultural hybridity, accelerated by festivities and processions, shaped not only spiritual practices but also the social order in the Camargue; becoming a zone of cultural improvisation – which would later be transformed under the influence of the Roman empire.[9] The Roman Empire, as an example of a heroic society, conquered not only by way of military force, but also by casting culture and social order as a political project.[10] In the initial worship of the Matres, women gathered, as druids, priestesses, or initiates – sisterhoods of witches who found kinship through shared rituals at sacred natural sites rather than through bloodlines. These pre-Roman customs, practiced at the fringes of the empire, gradually merged with traditions from the imperial center during Roman expansion. In this hybridization, the Romans swapped the Matres out for Juno, typically standing for family order and traditional motherhood, as well as the Iranian god Mithras.[11]

Mitras was a sun deity whose worship spread by traveling soldiers and merchants, who landed via the big port of Massalia (Marseille).[12] The altars for Artemis, Mother Juno, and Mithras joined the existing healing spring and well.[13] Many new shrines dedicated to Mithras were erected, often in natural or man-made caves, serving as sites of initiation and, possibly – if not only symbolically – bull sacrifices. As these shifts unfolded, gender roles were redrawn along rigid lines. Where once feminine spiritual authority thrived, patriarchal structures were imposed through centralized systems of law and belief and import of the Roman slave system.[14] This transformed the cultural and religious hybridity of the margins into something that now served imperial order.[15] The people at these fringes, pejoratively called pagani, were however able to maintain a certain distance and agency from the larger whole.[16] They were able to regain some autonomy over their habits after the fall of the Roman Empire, in part triggered by the disintegration of the Roman slave system by the 4th century CE, which transitioned into a Merovingian serfdom that granted land rights.[17] Feminist and proto-communist practices were considered commonplace in the time around and after the presumed arrival of the Saints at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and the Christianization of the neighboring mainland. For a long time, this region thrived on a coexistence of belief systems and benefited from blurred borders.

‘Course camarguaise’ in an arena in the South of France. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. From: Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections.[18]

II – Three Mary’s

As “paganism [was] truly a religion of place,”[19] these communities revived their local custom of the Matres, intertwining Mithran rites of bull-sacrifice with agricultural cycles and weather patterns – for example, during harvest celebrations. Once again, water worship became significant here, symbolizing the plenitude and renewal of nature and the charity of Mother Earth. Villagers engaged in ritual bathing in sacred springs, rivers, and lakes as part of summer solstice rites. While driving in the surrounding landscape of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, the car occasionally rocking from strong gusts of the Northern Mistral, I could not help but admire the endless vistas – a tapestry of lakes, marshes, arable rice and wheat fields, salt flats, grazing sites, and farms, reminding me of the Dutch waterscapes that had been turned towards production.

Landscape with traditional houses of the Camargue near Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. From: Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections. [20]

Eventually, Bishop Caesarius of Arles led campaigns to Christianize the south of France (from 502-542 CE)[21] systematically targeting these enduring pagan practices. The fortified village was taken over and renamed to Sancta Maria de Ratis, with ratis meaning either “raft” or “wooden island”.[22],[23] The cult of the Three Mary’s was incisively planted on the Camargue coast to replace the aforementioned ancient cult of the fertility goddesses. The spring, well, and the former shrines of Artemis and Mithras were swiftly repurposed as the foundation for Notre-Dame-de-la-Barque (Our Lady of the Raft), a fortified church in the tradition of the oppida. The local women, who continued to act as diviners and healers, were discouraged through social pressure and actively persecuted.[24]

Ironically, the legend of the Three Mary’s – symbolizing care and safety in refuge on new lands – was part of a new wave of foreign norms that appropriated indigenous value systems. Yet, it was also markedly intolerant of coexistence with paganism. Despite these efforts to convert the masses, remnants of the older pagan customs persisted; the image of communal water-worship was once again fluid enough to become part of the evolving religious landscape, now a “community Christianity”.[25] The processions and festivities were naturalized and synchronized with the ecclesiastical calendar, an important example being the festivities of John the Baptist that coincided with the harvest period and solstice. During these days, peasants were once again able to walk through the woods and vineyards to bathe in springs, lakes, and the sea – baptizing themselves, reminiscent of ancient rain prayers and Matres-cult.[26],[27]

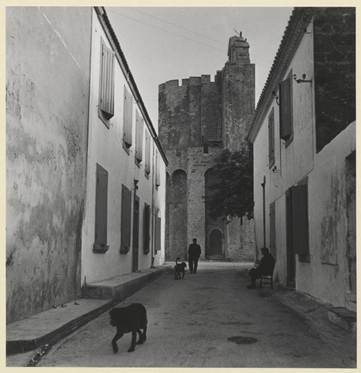

View on church Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. From: Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections [28]

III – And there was Sarah

The worship of Saint Sarah, protector of the Romani and other travelling peoples, took flight around the inscribing of the legend of the Three Mary’s in the 15th century, after inquiries of their holiness by King René of Anjou.[29] Her days of worship were grouped with the days of the Three Mary’s.

Document of the discovery of the relics of the Holy Mary’s. 23 November 1448. Reference B 1192 / Departmental Council 13 / Departmental Archives. All rights reserved. [30]

This happened not too long after the Romani landed first in the Camargue – around the mid-15th century – from Spain and, ultimately, India, still worshipping a folk pantheon.[31] It’s speculated that the ancestors of the Romani peoples themselves had to flee droughts and wars in India, their travels spreading them across Europe, Northern Africa, and West Asia. Their Sarah, too, is a unique merging of several cultural and religious elements: the servant Sarah (Sarah the Egyptian, or Sarah the Black) in the Catholic tradition, who travelled on the raft; the legend of a Rom leader named Sarah, who awaited the Three Mary’s on the shore and received their charity first by helping them come on land,[32] and the worship of multiple Eastern goddesses. According to the legend, Sarah led her people to the shores to await the Three Mary’s. Upon their arrival, Sarah helped them reach the shore by casting her flowing dress as a raft. Once landed, Saint Sarah supported the Marys’ survival through collecting alms.

Over time, the Romani people readily adopted Sarah, finding two points of recognition between Sarah’s story and their own arrival: first the identification with the goddess-mothers they brought along, and secondly, the popular French belief at that time that the Romani themselves were Egyptians.[33] The fluidity of water worship permeates through the Romani veneration of Saint Sarah, or Sarah the Black, Sara-la-Kali, which layers the worship of the Abrahamic mother Sara with the water immersion rites of Kali, the Hindu Divine Mother, the Rajput Indian cult of protector goddess Sati Sara[34], and mother goddess Astarte (Ishtar). The Romani’s water immersion rites, already present in their traditions, were further strengthened by these overlapping influences. As a result, the Romani were granted access to the crypt and church during the holy week of Saint Sarah, as well as the pilgrimage rites of the Marys – a rare form of tolerance from the Christian community.

IV – Community in times needed most

The worship of Saint Sarah is highly political in nature and plays with the gestures of lived/living memory, return, and communion – Sarah’s return to the sea, the pilgrims’ yearly gathering, a recurring stream of people, the transformative power of water immersion.[35]

The Camargue in the 18th and 19th centuries endured periods of societal decline in the eyes of the lordships of the mainland. The people of the delta were said to “feed on green frogs and pink flamingos.”[36] The cults of Saint Sarah and the Three Marys were once again obscured from view, evading the gaze of the people’s eye and likely falling into decline.

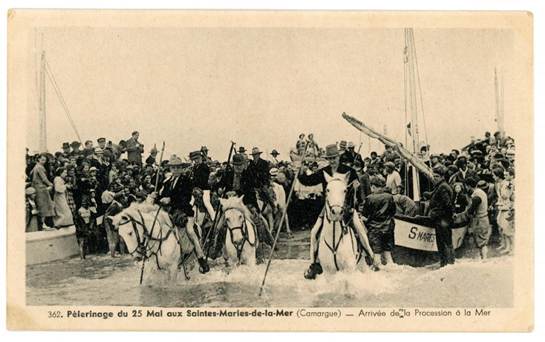

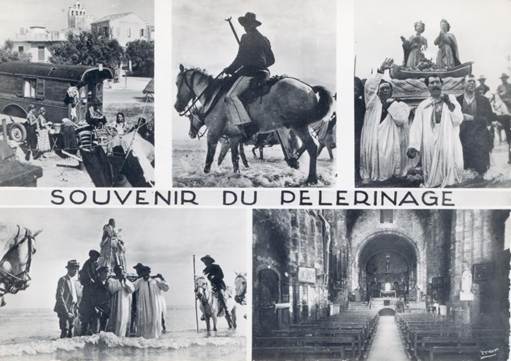

Around the period of the Second World War, during which Roma and Sinti peoples faced genocide in Europe[37], the centuries-old worship again gained traction. Two reasons can be given for this revival: first, the apparent need to restart waning tourism and lure visitors to the region. And secondly, to fulfil the proud wishes of some Gardians, including the prominent Marquis de Baroncelli, to put a spotlight back on this tradition.[38] Many postcards from around this period bear testimony to this. The Camargue once again became the location to renew relationships, find community, and practice tradition. More openly, coexistence became a mutually beneficial model for the region. At the end of May, the week of veneration sees the town, church, and crypt filled with thousands of Romani pilgrims and other visitors. Saint Sarah is carefully tended to,[39] adorned with layers of fabric offerings that overflow her statue – echoing the South Indian custom of Chitraiya Bhavani (Our Lady of the Rags), where textiles become imbued with divine power. Worshippers spend the night at the church, guarding the Saint. The next day, four Gardians carry the statue in a procession to the sea, a task passed down through generations. This marks the beginning of a week of festivities: the statues of the Three Mary’s are carried from the church on a raft and immersed in the sea, young babies and toddlers are baptized, a big market is held, bulls are branded in the traditional Ferrade, and bullfights take place in the stadium near the beach.

Marquis de Baroncelli Javon precedes the procession. Postcard with photograph by Mireille, ca. 1930-1940. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. [40]

The arrival of the procession on May 25th. Postcard with photograph by Photo George, ca. 1930-1940. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer [41]

Saint Sarah. Postcard, n.d. Reference 6 Fi 8970 / Departmental Council 13 / Departmental Archives. All rights reserved. [42]

Saint Sarah adorned in her crypt, photographed during my visit. December 2024.

Pilgrimage souvenir. Postcard with photograph by Les Éditions “Mar”, ca. 1950. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer [43]

Symbolizing both refuge and prosperity, the waters of the Camargue and the Mediterranean have long been entwined with the historical movements of minorities and the hybridization of their practices. From Gallic sacred springs and wells – later co-opted into Catholic churches and chapels – to the veneration of Sarah the Black by persecuted Romani communities, the Camargue has fostered traditions of resilience, community, and hospitality despite hardship and empire.

In the Camargue, borders and origins have never been fixed. History reveals how the ebb and flow of people and ideas – through migration and settlement – have shaped the region, mostly in generative ways. Back in Marseille, the richness of cultures meeting one another is immediately imparted onto me. The scents of Moroccan, Tunisian, Syrian, and Senegalese food greet me, as do the many different faces running shops in the Noailles district. Yet, while the arrival of the Mary’s is celebrated, carried to shore in their boat by Sarah, herself a refugee, I cannot help but draw a connection to shifting tides in the Camargue; notably the impacts of present-day border and refugee politics in so-called ‘Fortress Europe’, the center of democratic values, our contemporary ‘empire’. Just as rising sea levels threaten traditional livelihoods in the Camargue, the far-right vote has taken hold in the region over the past decade. The 2012 French election race was a crucial first expression of rightwing sentiment, with populist rhetoric amplifying local citizen’s feelings of dispossession and alienation in a globalizing world, as well as an already traditionalist outlook on politics.[44] Over the years, the Rassemblement National has become a political mainstay. In the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region – unlike anywhere else in France – a strong correlation exists between areas with higher rates of immigration and significant support for the far right.[45] After the French government shut down the Calais camp and designated villages in Southern France as host sites, large protests erupted. Despite increasingly vocal calls to tighten border control, between 2023 and 2024, a thousand migrants still were smuggled through France and Spain, crossing the sea in precarious dinghies – some ultimately arriving in Marseille, Arles, and surrounding towns. Beyond the countless deaths, which only occasionally make the headlines, those who survive the journey face further hardship on land. Many remain trapped in legal limbo, met not with open arms but with systemic indifference. Stigmatized and categorized according to degrees of vulnerability, their access to care becomes highly conditional – life-saving assistance left in the hands of those willing to defy a deadly system.

Seeking community and agency, today’s migrants, much like those before them, navigate uncertain waters – both literal and bureaucratic. Unlike the celebrated arrival of the Marys, their presence is met with hostility rather than sanctuary. And unlike the agency of Sarah, the migrants are not seen as contributing to any story or valued in coexistence. The same waters that once symbolized refuge and renewal have become sites of exclusion and loss, exposing the contradictions of a Europe that venerates histories of migration while rejecting its present realities.

Endnotes

1 Unknown, Camargue. The Gardian’s cross. Horses in the Camargue marshes. House and Gardian’s cross, Departmental Archives of Bouches du Rhône, accessed March 11, 2025, https://www.archives13.fr/ark:/40700/vtaf3489f7156752ac3/dao/0/1/idsearch:RECH_03f9696c78e4dc50e3e4c03a1e52bf50?id=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.archives13.fr%2Fark%3A%2F40700%2Fvtaf3489f7156752ac3%2Fcanvas%2F0%2F1

2 Colleen E. Donnelly, The Marys Of Medieval Drama (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2016), 7.

3 William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994)

4 David Graeber, The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World…: Essays (London: Allen Lane, 2024), 46.

5 James C. Anderson, jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 242.

6 John Bostock and H.T. Riley, The Natural History. Pliny the Elder (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855), accessed online March 11, 2025

7 Livius. 2003. “Matres”. Livius. Last modified January 3, 2020. https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/matres/

8 Eric W. Edwards. “The Matres of Ancient northern Europe.” Eric Edwards Collected Works. Last modified March 3, 2014. https://ericwedwards.wordpress.com/2014/03/03/the-matrones-of-the-ancient-celts/

9 William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 50.

10 A heroic society, found along the Mediterranean, characterised itself by way of competitiveness, blood-sacrifice as ritual, and focus on material treasure. See also: David Graeber, “Culture as Creative Refusal”, in: The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World…: Essays (London: Allen Lane, 2024), 108.

11 Mucem. 2015. “Divine migrations.” Mucem. https://www.mucem.org/en/divine-migrations

12 James C. Anderson, jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 145.

13 Joyce Zonana. 2016. “Our Ladies of Sea, Earth, and Sky.” Feminism and Religion. https://feminismandreligion.com/2016/06/25/our-ladies-of-the-sea/

14 Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2014), 23.

15 Wigodner, Alena. “Gendered Healing Votives in Roman Gaul: Representing the Body in a Colonial Context.” American Journal of Archaeology. University of Chicago Press, October 1, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.123.4.0619.

16 William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 44-46.

17 Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2014), 23.

18 ‘Course camarguaise’ in an arena in the South of France. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. From: Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections, accessed April 13, 2025. https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/3755711

19 William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 47.

20 Landscape with traditional houses of the Camargue near Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections, [Accessed March 14, 2025] https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/3755570?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=e08cdff08481b7235117&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=9

21 William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

22 Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul

23 Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 179.

24 The healing practices of local women were taken over by Church clerics through approved forms of divination and manufacturing of amulets.

25 William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 225.

26 Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul, 225.

27 Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 182.

28 View on church Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections, [Accessed March 14, 2025] https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/1894193

29 Bones of the Marys and Sarah, and three pedestals, two dedicated to goddess Juno and one serving as a Mithran bull-sacrifice platform (taurobolium), were found; the latter interpreted as ‘pillows’ in the cult of the Marys. (Clebert, The Gypsies)

30 Document of the discovery of the relics of the Holy Mary’s. 23 November 1448. Departmental Archives of Bouches du Rhône, https://www.archives13.fr/documents-du-mois/visualiser/24/n:269?vx=1648.5&vy=-2352.5&vr=0&vz=2.14789 [Accessed March 15, 2025]

31 Officially, the date of Gypsies arriving in France is marked as 1419. Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 54, 180.

32 Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 179.

33 From here we also get the term ‘gypsy’, often not the preferred naming or even pejorative; Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 72.

34 Zina Petersen; “Twisted Paths of Civilization”: Saint Sara and the Romani. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 1 September 2014; 26 (3): 310–322. doi: https://doi.org/10.3138/jrpc.26.3.310

35 Marc Bordigoni. “Le pèlerinage des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer”. In Les fêtes en Provence autrefois et aujourd’hui, edited by Régis Bertrand and Laurent-Sébastien Fournier. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pup.15322.

36 Marc Bordigoni. “Le pèlerinage des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer”. In Les fêtes en Provence autrefois et aujourd’hui, edited by Régis Bertrand and Laurent-Sébastien Fournier. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pup.15322.

37 In France, there was an order to restrict movement of Romani and travellers, there was “No overall racial deportation of Roma, but more than 200 French Roma were murdered in Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Auschwitz-Birkenau”. Council of Europe Portal. “Factsheet on the Roma Genocide in France”, Roma Genocide, accessed March 15, 2025: https://www.coe.int/en/web/roma-genocide/france

38 Avignon et Provence, “Gypsy’s Pilgrimage in Les Saintes Maries de la Mer”, accessed March 11, 2025: https://www.avignon-et-provence.com/en/traditions/gypsys-pilgrimage-saintes-maries-de-mer

39 During my visit, I saw the statue of Saint Sarah, dressed in seven flowing garbs, surrounded with candles, portraits of Romani, and other objects of devotion, sitting in the crypt. The crypt is well-visited, and the Saint looks well-tended to – calmly looking on to the devotees.

40 Marquis de Baroncelli Javon precedes the procession. Postcard with photograph by Mireille, ca. 1930-1940. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. https://www.culture.eligis-web.com/?search_hash=167e06f1ff1510

41 The arrival of the procession on May 25th. Postcard with photograph by Photo George, ca. 1930-1940. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. https://www.culture.eligis-web.com/?search_hash=167e06f1ff1510

42 Saint Sarah. Postcard, n.d. From: Departmental Archives of Bouches du Rhône https://www.archives13.fr/ark:/40700/vta1210d80f7a05dc4a/dao/0/1/idsearch:RECH_f9781e74d0447195e4dc2284de5bc8ee?id=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.archives13.fr%2Fark%3A%2F40700%2Fvta1210d80f7a05dc4a%2Fcanvas%2F0%2F1

43 Pilgrimage souvenir. Postcard with photograph by Les Éditions “Mar”, ca. 1950. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, https://www.culture.eligis-web.com/?search_hash=167e08762cb904

44 Geert De Clercq, “Bulls, Suburbs and the French Far Right,” Reuters, June 7, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-france-election-camargue/bulls-suburbs-and-the-french-far-right-idUKBRE8560XJ20120607/. Accessed April 13, 2025.

45 Virginie Martin, “The South of France Is a Marine Le Pen Stronghold – but Has She Hit a Ceiling?,” The Conversation, n.d., https://theconversation.com/the-south-of-france-is-a-marine-le-pen-stronghold-but-has-she-hit-a-ceiling-165568. Accessed April 13, 2025.

[1] Unknown, Camargue. The Gardian’s cross. Horses in the Camargue marshes. House and Gardian’s cross, Departmental Archives of Bouches du Rhône, accessed March 11, 2025, https://www.archives13.fr/ark:/40700/vtaf3489f7156752ac3/dao/0/1/idsearch:RECH_03f9696c78e4dc50e3e4c03a1e52bf50?id=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.archives13.fr%2Fark%3A%2F40700%2Fvtaf3489f7156752ac3%2Fcanvas%2F0%2F1

[2] Colleen E. Donnelly, The Marys Of Medieval Drama (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2016), 7.

[3] William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994)

[4] David Graeber, The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World…: Essays (London: Allen Lane, 2024), 46.

[5] James C. Anderson, jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 242.

[6] John Bostock and H.T. Riley, The Natural History. Pliny the Elder (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855) [Accessed online March 11, 2025] https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D3%3Achapter%3D5

[7] Livius. 2003. “Matres”. Livius. Last modified January 3, 2020. https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/matres/

[8] Eric W. Edwards. “The Matres of Ancient northern Europe.” Eric Edwards Collected Works. Last modified March 3, 2014. https://ericwedwards.wordpress.com/2014/03/03/the-matrones-of-the-ancient-celts/

[9] William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 50.

[10] A heroic society, found along the Mediterranean, characterised itself by way of competitiveness, blood-sacrifice as ritual, and focus on material treasure. See also: David Graeber, “Culture as Creative Refusal”, in: The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World…: Essays (London: Allen Lane, 2024), 108.

[11] Mucem. 2015. “Divine migrations.” Mucem. https://www.mucem.org/en/divine-migrations

[12] James C. Anderson, jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 145.

[13] Joyce Zonana. 2016. “Our Ladies of Sea, Earth, and Sky.” Feminism and Religion. https://feminismandreligion.com/2016/06/25/our-ladies-of-the-sea/

[14] Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2014), 23.

[15] Wigodner, Alena. “Gendered Healing Votives in Roman Gaul: Representing the Body in a Colonial Context.” American Journal of Archaeology. University of Chicago Press, October 1, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.123.4.0619.

[16] William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 44-46.

[17] Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2014), 23.

[18] ‘Course camarguaise’ in an arena in the South of France. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. From: Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections, accessed April 13, 2025. https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/3755711

[19] William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 47.

[20] Landscape with traditional houses of the Camargue near Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections [Accessed March 14, 2025] https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/3755570?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=e08cdff08481b7235117&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=9

[21] William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

[22] Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul

[23] Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 179.

[24] The healing practices of local women were taken over by Church clerics through approved forms of divination and manufacturing of amulets.

[25] William E. Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 225.

[26] Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles: the making of a Christian community in late antique Gaul, 225.

[27] Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 182.

[28] View on church Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer. Emmy Andriesse, between 1951 and 1952. Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections, [Accessed March 14, 2025] https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/1894193

[29] Bones of the Marys and Sarah, and three pedestals, two dedicated to goddess Juno and one serving as a Mithran bull-sacrifice platform (taurobolium), were found; the latter interpreted as ‘pillows’ in the cult of the Marys. (Clebert, The Gypsies)

[30] Document of the discovery of the relics of the Holy Mary’s. 23 November 1448. Departmental Archives of Bouches du Rhône, https://www.archives13.fr/documents-du-mois/visualiser/24/n:269?vx=1648.5&vy=-2352.5&vr=0&vz=2.14789 [Accessed March 15, 2025]

[31] Officially, the date of Gypsies arriving in France is marked as 1419. Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 54, 180.

[32] Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 179-180.

[33]From here we also get the term ‘gypsy’, often not the preferred naming or even pejorative; Jean-Paul Clebert, The Gypsies (London: Penguin Books, 1974), 72.

[34] Zina Petersen; “Twisted Paths of Civilization”: Saint Sara and the Romani. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 1 September 2014; 26 (3): 310–322. doi: https://doi.org/10.3138/jrpc.26.3.310

[35] Marc Bordigoni. “Le pèlerinage des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer”. In Les fêtes en Provence autrefois et aujourd’hui, edited by Régis Bertrand and Laurent-Sébastien Fournier. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pup.15322.

[36] Marc Bordigoni. “Le pèlerinage des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer”. In Les fêtes en Provence autrefois et aujourd’hui, edited by Régis Bertrand and Laurent-Sébastien Fournier. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pup.15322.

[37] In France, there was an order to restrict movement of Romani and travellers, there was “No overall racial deportation of Roma, but more than 200 French Roma were murdered in Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Auschwitz-Birkenau”. Council of Europe Portal. “Factsheet on the Roma Genocide in France”, Roma Genocide, accessed March 15, 2025: https://www.coe.int/en/web/roma-genocide/france

[38]Avignon et Provence, “Gypsy’s Pilgrimage in Les Saintes Maries de la Mer”, accessed March 11, 2025: https://www.avignon-et-provence.com/en/traditions/gypsys-pilgrimage-saintes-maries-de-mer

[39] During my visit, I saw the statue of Saint Sarah, dressed in seven flowing garbs, surrounded with candles, portraits of Romani, and other objects of devotion, sitting in the crypt. The crypt is well-visited, and the Saint looks well-tended to – calmly looking on to the devotees.

[40] Marquis de Baroncelli Javon precedes the procession. Postcard with photograph by Mireille, ca. 1930-1940. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. https://www.culture.eligis-web.com/?search_hash=167e06f1ff1510

[41] The arrival of the procession on May 25th. Postcard with photograph by Photo George, ca. 1930-1940. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. https://www.culture.eligis-web.com/?search_hash=167e06f1ff1510

[42] Saint Sarah. Postcard, n.d. From: Departmental Archives of Bouches du Rhône https://www.archives13.fr/ark:/40700/vta1210d80f7a05dc4a/dao/0/1/idsearch:RECH_f9781e74d0447195e4dc2284de5bc8ee?id=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.archives13.fr%2Fark%3A%2F40700%2Fvta1210d80f7a05dc4a%2Fcanvas%2F0%2F1

[43] Pilgrimage souvenir. Postcard with photograph by Les Éditions “Mar”, ca. 1950. Courtesy of the city of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, https://www.culture.eligis-web.com/?search_hash=167e08762cb904

[44] Geert De Clercq, “Bulls, Suburbs and the French Far Right,” Reuters, June 7, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-france-election-camargue/bulls-suburbs-and-the-french-far-right-idUKBRE8560XJ20120607/. Accessed April 13, 2025.

[45] Virginie Martin, “The South of France Is a Marine Le Pen Stronghold – but Has She Hit a Ceiling?,” The Conversation, n.d., https://theconversation.com/the-south-of-france-is-a-marine-le-pen-stronghold-but-has-she-hit-a-ceiling-165568. Accessed April 13, 2025.