It’s been seven years since Daan Roggeveen and Michiel Hulshof published How the City Moved to Mr. Sun, the story of mass urbanization in China. It looked specifically at the mechanisms behind this phenomenon and the challenge to host the next 300 million people during the coming twenty years (starting from 2010). The book already hinted at the question underpinning Roggeveen’s latest book, Progress and Prosperity: Is this city model a formula for success exportable to other regions in this world? Are we looking at the next urban model, after the Italian and the American one? And how does the formula perform? After Ole Bouman’s reflection on the Venice Architecture Biennale two weeks ago, this is the second prelude to Volume #54: On Biennials with a special on the UABB\Shenzhen.

VOLUME: What triggered the book? What made you take this initiative?

Daan Roggeveen: Directly after the publication of How the City Moved to Mr. Sun, I became curator of the public program at the University of Hong Kong. I had carte blanche and could organize lectures, symposiums, exhibitions. So, I started to redefine an agenda of issues in China’s urban development that I thought to be relevant to be discussed with students and the audience at large.

The first topic I addressed was Money; the relation between urban development and the financial world, how these two are intertwined and how the cross-over works. The idea was to force the (future) architect to think of that realm, of the financial context they must work in. The title of that lecture series was ‘Follow the Money’ – inspired by All the President’s Men: if you keep asking where the money comes from, you will understand the forces at play.

A second topic was Forecast. How can architects change from just following developments to proactively act on the future. And a third yet was the Countryside. Five years ago, these topics were not as widely debated as today.

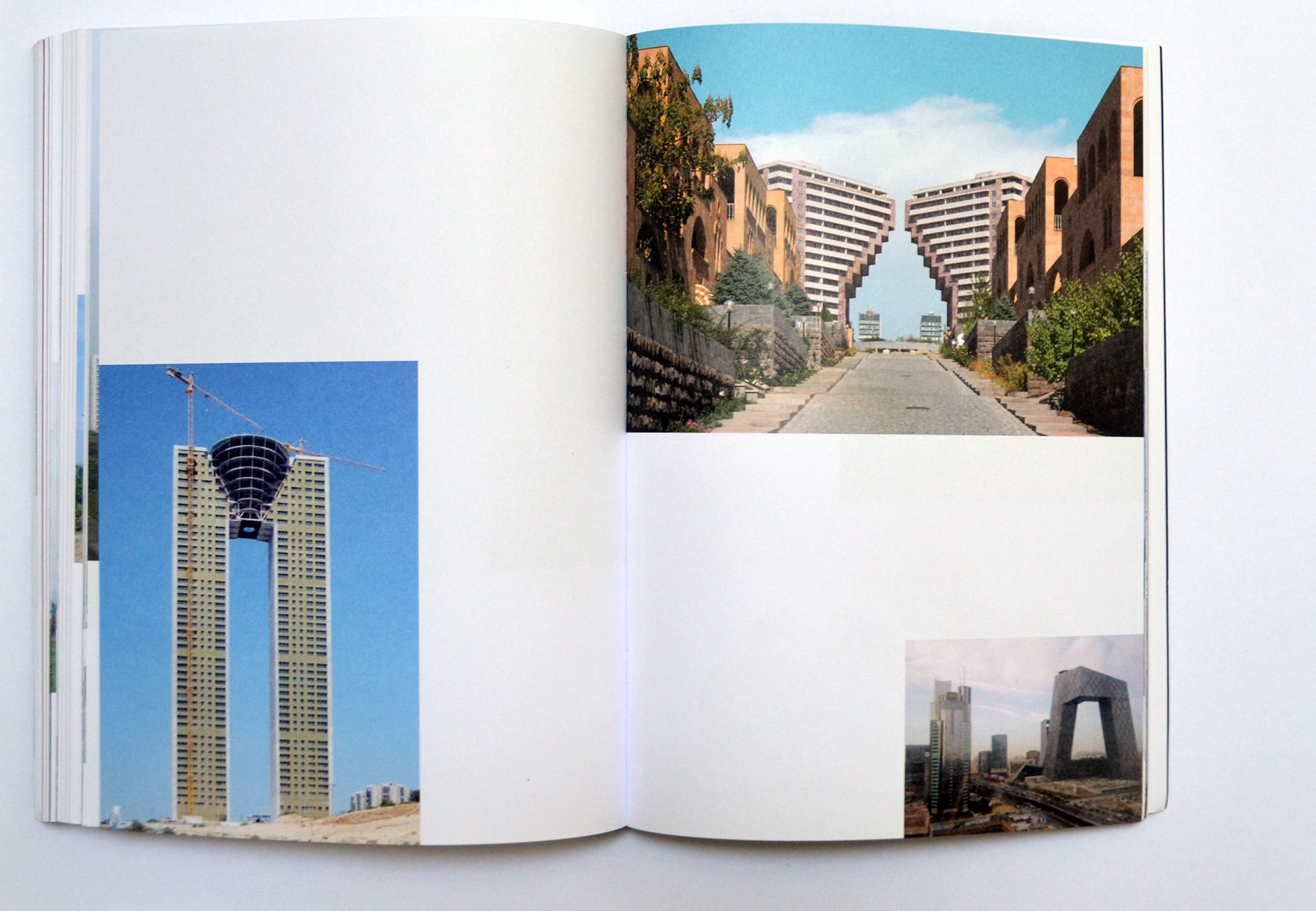

Gradually a red thread started to emerge, which was ‘progress and prosperity’. China is very much forward-looking in its ambitions and in its urban development. But simultaneously, we started to see that China is not unique in that approach; in the idea that tomorrow will be better than today, in the physical component. This is happening everywhere, particularly in the Global South. And then there was this element of Progress, moving from physical to non-physical: from hardware to software, from mega event to music festival, this was becoming an important development in China. We know China for its skyscrapers and airports, but the soft side is as important nowadays.

VOLUME: So that discovery was the start of your research, with this book as a result?

DR: The program allowed me to bring all these people together and start a conversation with them, and that lead to these contributions. It took almost five years to make the book; quite a long time, roughly the same as for a building. A lot happened during that period – with me and with China – making the urgency for this book much more well-defined. The balance between progress and prosperity became much more visible in China and therefore also in the book.

VOLUME: What is the urgency, you’re mentioning?

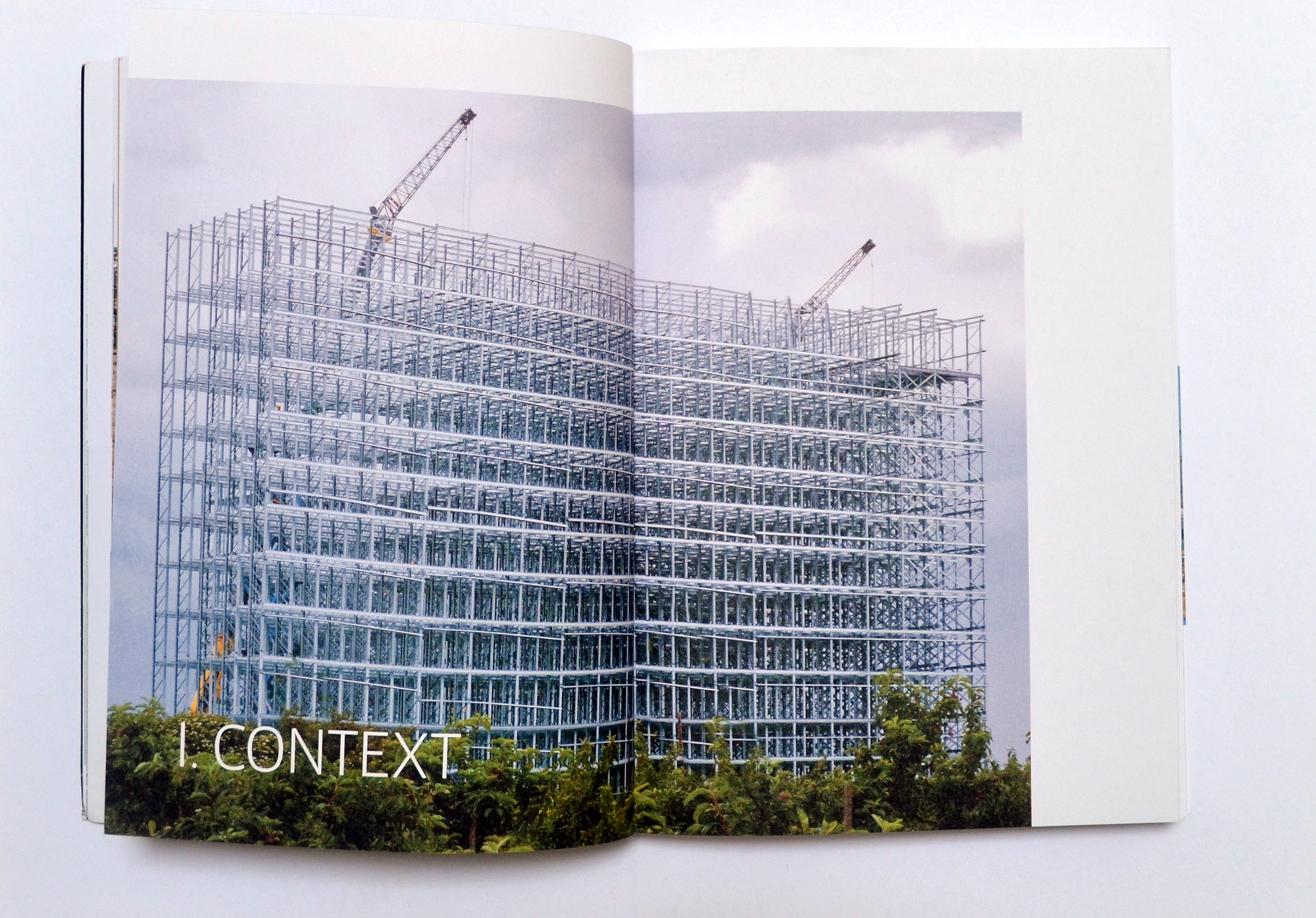

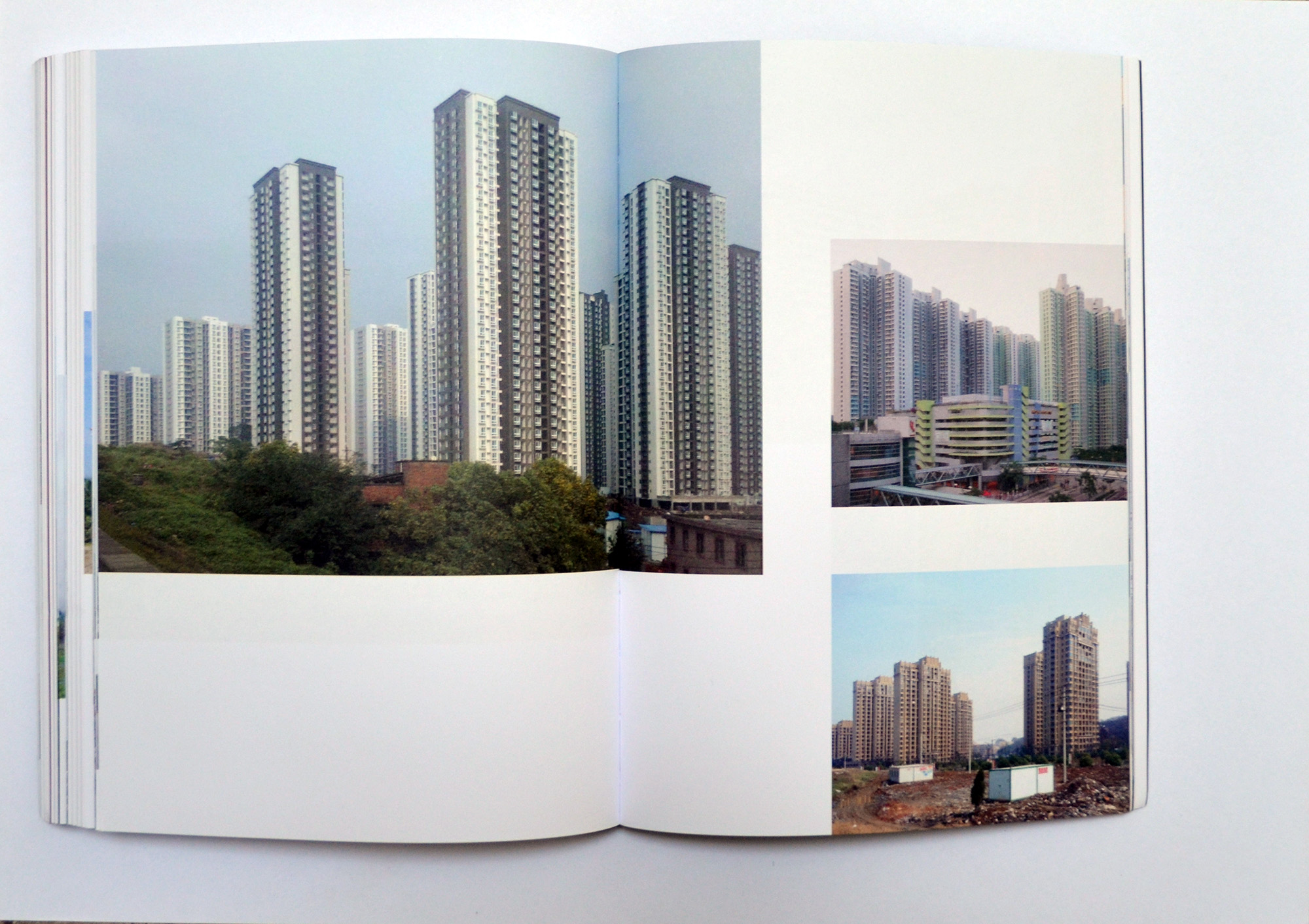

DR: Five or six years ago the Chinese cities were growing, mainly driven by infrastructure. ‘When we build, they will come’; an unhealthy kind of development. There was oversupply, the main focus was quantity, not about quality. But in 2014/15 China witnessed an economic crash that forced developers and governments in China to redefine their strategies. Cities had to do the same, since China was rapidly changing from an industrial society into a service-oriented society. This transformation has happened really during the past five years and it is coinciding with a much tighter form of control by the government in fighting corruption and defending the party line. So, you see the shift from second to third industrial revolution, the short but intense economic crisis, and this stricter regime all coming together.

On the one hand it raised questions about the current urban model in China and on the other hand you see the changing position of China in the world. China is taking over as global power. So, in the book we say that China’s urban model will have a global impact. The current developments in world politics only support that argument.

VOLUME: Your earlier book/study on China’s presence in Africa focused on China’s presence abroad. This one focuses on urbanization in China, but also as an export model.

DR: Yes, although this is more nuanced in the book. The book consists of four sections. It starts with Shanghai, zooms out to prosperity in China at large, then looks at progress, the soft side of urbanization. In this section we start to suggest global impact, for instance in the essay about mega events by Amsterdam-based architects XML.

And finally, the essay by Eric Tabuchi shows found footage on destruction and construction from all over the planet. That’s more or less the mental map of the book.

VOLUME: How would you describe the character of the book? Did it start from an observation, or is it based on data collection and mapping? What kind of lens did you use?

DR: It started with some observations which led to an argument. The project was based on a premise, sure, but only seven months ago it became fully clear what the book is about. It grew and developed in the making.

VOLUME: I ask because the blurb on the cover ends in a question: “Can this [Chinese] metropolis be a blueprint for cities worldwide?”

DR: The definition of what the model is depends very much on your point of reference. Sitting in the city centre of Amsterdam it is questionable if that type of development is ideal for this part of the world. But for large parts of the world, the Chinese urban model is more attractive than the model we developed in the West. Simply because the Chinese model is more effective in addressing the urgencies the world is facing, even though the model has huge downsides in terms of the environment, of the democratic impact, in terms of its elegance in the relation with its citizens. But if you look at urbanization in India, Africa, parts of the Middle East, the Chinese way can be successful. But it may need to be tweaked. David Gianotten, who contributed to the book, is very clear about that. To apply the Chinese model in the West it has to be modified, so it’s not a 1:1 export.

VOLUME: If I understand Gianotten correctly, he says that there is something to learn from the Chinese experience, but what one can take home is a way of working, not a model per se.

I don’t see that much tweaking in the way the Chinese model is being applied in for instance Myanmar.

DR: That is the weak point in how the Chinese export their model. They don’t really connect to where they’re going. And this explains also why so many attempts in Africa and Asia actually fail. Chinese companies are not great in communication, it’s not their strongest suit. And they simply don’t consider the various contexts in which they’re operating. If they want to do a railroad in Ghana, they do it just like the way they’re used to. There is no debate. The fact that landownership is differently organized in Ghana than in China is none of their concern.

VOLUME: And the other way around, what can you bring to China?

DR: It’s not easy to answer. I’ve been there for ten years now and during that period Chinese planners and architects have developed and educated themselves tremendously. And not just designers, also clients and governments have developed profoundly. Some of our clients visit the Venice Biennale for instance, and they know very well what’s going on in the world. One of the opportunities is to organize yourself around a theme, like the Dutch do with water. Another one, stemming from my personal experience, is slowness. Stop running and start thinking. That also selects clients interested in such an approach. You cannot outpace the Chinese system, so maybe the other direction is a good strategy.

VOLUME: But that impacts the very notion of progress, right? This slowing down introduces a new definition of progress, contrary to what the notion usually represents. So, what is your definition?

DR: That is a fundamental question that Chinese cities certainly ask; what do we have our citizens to offer? Just economic growth and employment? Clearly, that’s not sufficient anymore. That has been the major shift of the past five to eight years. China’s political structure is based on the premise that economically, tomorrow will be better than today. But the moment growth slows down, people start to ask questions. What else do we get?

Singapore is a very interesting example where this has already happened. When economic growth slowed down, the government stepped in to push for the softer values in life. The same is happening in China right now. China’s cities are undergoing a museum boom, for instance. But there has also been a massive growth in music festivals. Seven years ago, there were no rock festivals in China and now there may be a thousand or more, often supported by the government; passively by allowing and actively by (co)financing them. The same happens here where the cultural agenda is very much intertwined with the agenda of the government.

But now we’re entering a new situation in China in terms of ‘culture production’. Who will pick up the bill? In the US it’s patrons and corporate sponsors; in Europe it is the government. The question is what this development will be in China? We see a tendency towards private museums, but this isn’t really well-defined yet. Museums are recognized as key drivers for urban development, but the model hasn’t crystallized fully.

VOLUME: As urban program you mention museums and cultural activities like festivals; but these are also serving an financial agenda. This transformation towards a service economy is targeting a very specific part of the population. How does this policy relate to the Chinese urban population at large?

DR: Sticking to the example of museums: these are not just museums for contemporary art. Recently, the new Natural History Museum in Shanghai opened – it attracts the urban population at large. So, there are large parts of the cultural field that are now politically speaking ‘safe’; these days, no one will be offended by a Mozart concert.

And still, cultural production like contemporary art can be a catalyst for urban development. In the book there is the story about Dr. Sun Jiwei, who started his career as a mayor of a district in the outskirts of Shanghai and made his way through various districts. Most recently he became the mayor of Pudong, the CBD of Shanghai. In every situation he used architecture as a push factor for urban development.

Like the Eye Film Institute building here in Amsterdam, these buildings should be emblematic and attract investment. He has used that model several times. The latest is the new West Bund development with four new museums to spur a larger waterfront development.

VOLUME: Okay, that is one side of the story. Let’s move to another side that is not so much mentioned in the book. It has all to do with the urban legacy that is around now, the urban fabric that is present, that was done in the (recent) past and that needs reworking or at least needs attention. The upcoming UABB Biennale in Shenzhen focuses on the urban village as phenomenon, for instance. The Urban Village or Village in the City is a legacy reflecting very specific Chinese conditions, producing a unique urban landscape. It is complex and complicated, sensitive perhaps. So, what is your take on that part of Chinese urban development, that part of the story?

DR: I’m super happy that the UABB addresses this topic and puts it on the agenda. I think it’s late, since in Shenzhen most urban villages in the inner city are gone. Same for the Lilongs in Shanghai and Hutongs in Beijing. It’s very late. Nevertheless, it’s good to have the debate.

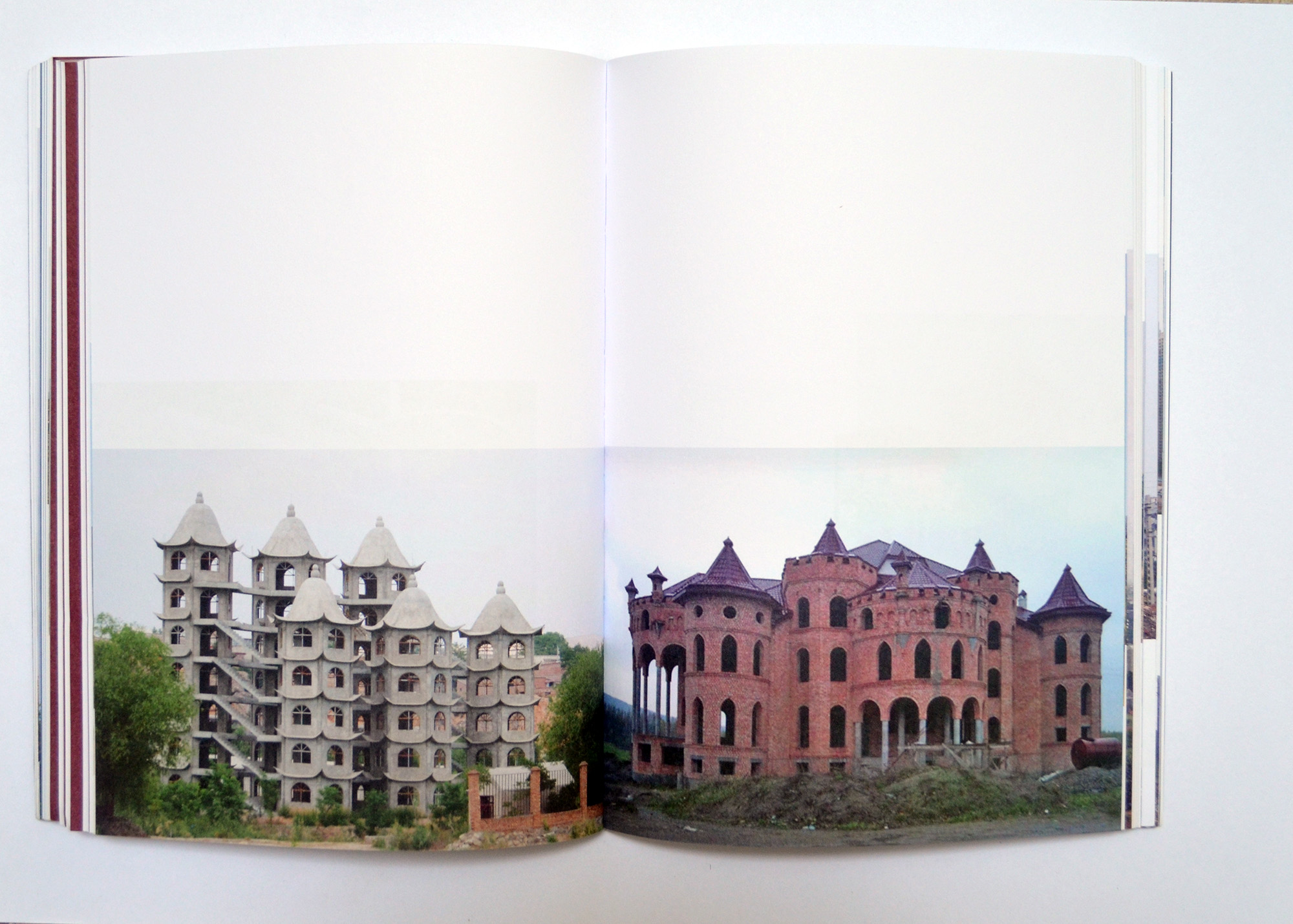

But a more urgent question would be what to do with the palimpsest of what we’re creating now. I think that’s far more important and urgent. At present, we’re creating so much ‘rubble’ that requires revamping, reprogramming and remodelling in two or three decades; it’s a huge question. These residential neighbourhoods, the compounds, all these mono programmatic office parks; large part of China has been and is being constructed as if CIAM is still alive. I hope this gigantic question can be a topic in this biennale as well.

VOLUME: Do you think that architects like you can bring something to China in relation to this issue?

DR: Yes, I do. We’re dealing with the legacy of modernism as well. Think of the latest Mies van der Rohe award for NL Architects’ refurbishment of a Bijlmermeer flat in Amsterdam. That recognition was also quite late, I think.

VOLUME: In your book you mention this notion ‘the New Normal’. You give the Chinese interpretation of that term, but there are many different ones circulating at present. So, what is yours?

DR: The Chinese government defines the New Normal as an understanding of the present in which growth is not the only, sacred measure of success. For many years, China had a double digit economic growth. Next, was a phase in which eight percent growth was the norm, considered absolutely necessary to provide enough jobs and upkeep the people’s individual welfare level. But now, after the crisis of 2014 and 2015, the government has indicated that economic growth alone is not enough for a healthy development of the country. Education, healthcare, the environment and clean air, are equally important.

It’s very good that the administration made that shift. It was very clear that the country was facing huge environmental issues. But it has to do with the transfer of Chinese society from an industrial economy to a service oriented one, less focusing on growth and export as such. This all is part of that ‘New Normal’; slowing down and focusing more on quality and less on quantity.

VOLUME: Does that include the countryside as well or is it still about the urban condition exclusively?

DR: That’s part of it. One of the bigger points of attention is town development, meaning the urbanization of the countryside by pushing smaller villages to grow into bigger towns and to make the farmers leave their farms and move into high-rises with proper water, bath and kitchen but without the possibility to farm for a living. So, what first happened in the inner cities is now happening in the countryside. This is all very top down. We present some examples in the book in the interview with Ou Ning, in which he describes different governmental models for this rural urbanization, which has not been very successful so far. There is a serious need for a model that can transform the rural reality, acknowledging the fact that the poverty gap between farmers and urban population is growing. In China, the Gini index – the difference between the highest and lowest incomes – is bigger that in the US, which is ridiculous for a communist country of course. And when you have this urban/rural divide, that becomes a recipe for Trumpism! That’s is something the government clearly wants to avoid.

Second is that cities need a pressure valve in developing tourism. The middle class of urbanites are becoming interested in their own history and therefore want to explore their country. That asks for an infrastructure for tourism. Once you overlay these two, that creates a viable economic model for the countryside and redirects capital flows to the countryside. There’s more of course, like the food production, that has to be scaled up. And through the internet, countryside production can be channelled into the city.

VOLUME: And how does that relate to the hukou policy?

DR: Cities are testing on a local level now. Previously, the government would be confident that farmers would give up their countryside hukou and apply for a city hukou. The current trend is that farmers stick to their land. It is their last resort when everything else fails. During the 2008 crisis, millions of people had to move back to the countryside, but they could pick up farming again, because they still had their land.

That’s also something we discovered, one of the most interesting parts I think, that the bigger phenomena are similar comparing China and the West: migration, one’s connection with the homeland or what used to be your homeland, the legacy of modernism and state capitalism.

Another aspect of this is that China used to be behind, busy catching up, but now you see that in some areas China is ahead of the West.

Take the relation between the virtual and the urban. For instance, the bike sharing scheme that’s being exported to Rotterdam and other European cities now. And I have the feeling that there is more ahead, although I cannot predict what exactly. The political structure in China allows for large scale implementation of new ideas. Only a couple of years ago every financial transaction in China would be done in cash. Nowadays there is hardly any cash anymore.

VOLUME: Maybe a last prediction then; China had the advantage to be underdeveloped, so could develop at a far faster pace than post war Europe and the US at the time. Now it arrives at a level where things are getting more complex and maybe also more complicated. That may slow down China’s capacity to change and grow. Do you see that already happening?

DR: If we talk how to navigate the legacy of this fast growth period, one-liners don’t work anymore. It was a ‘one off’ at the time, a one of for 500 million people, but still. You cannot ditch it and start anew. So now engagement and community building come into play. The approach should be more holistic and elegant. That will slow down the process, but the outcome can also be more layered, interesting and diverse. Exciting times to come!

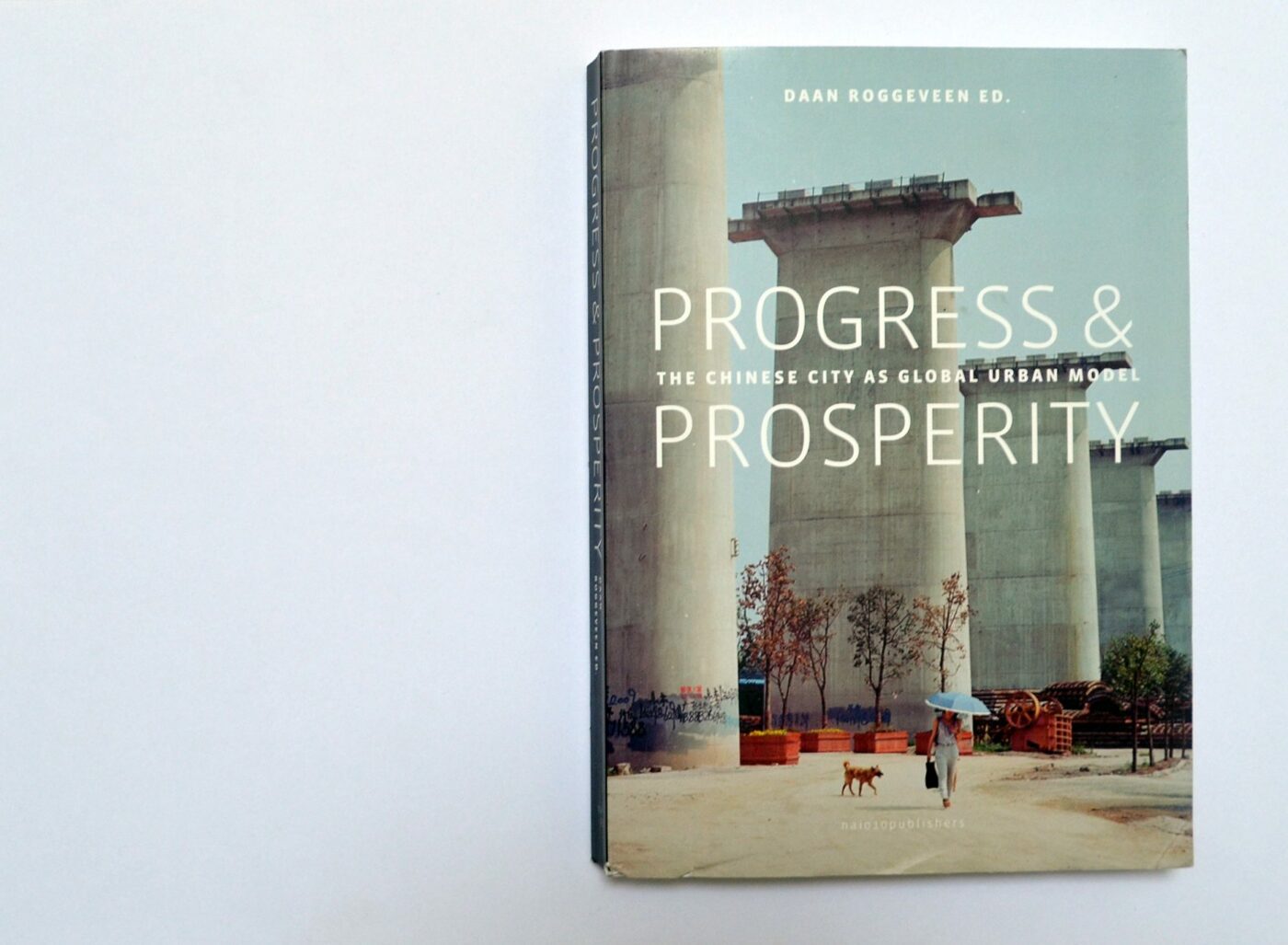

Daan Roggeveen (ed.), Progress & Prosperity. The Chinese City as Global Urban Model. Rotterdam: NAI 010 Publishers, 2017.