CASE ALFA COLLEGE

Scope

Project – Renovation of the school’s main building to extend its lifespan by twenty years or more, and dismantling and clearing of the outbuildings.

Incentive – The student population at Voltastraat had declined, rendering the site excessively large. Moreover, the complex suffered from structural obsolescence,including insufficient insulation and inadequate installations, along with an outdated aesthetic.

Project Size – Living Lab: 2,500 sqm; Renovation building parts A, C, D and E: 14,000 sqm; Demolition building part B: 3,500 sqm

Location – Alfa-college Voltastraat, Hoogeveen (NL)

Time Period – 2017-2021

Circular and Sustainable Ambitions – The renovation centered around four primary themes: energy efficiency, circularity, creating a healthy indoor environment, and incorporating nature.

Under the energy efficiency theme, the most tangible and quantifiable achievement was the reduction from 127 kWh/sqm per year to 43 kWh/sqm , comfortably surpassing the ‘Paris proof standard’ of a maximum of 70 kWh/sqm.

The circular handling of waste was (partly) elucidated through the material flow analysis. This analysis revealed that a substantial portion underwent processing in a lower-grade manner (recycling, 39%) or even a very low-grade manner (recovery, 24%). Consequently, adjustments were implemented in the process by thoughtfully designing the interior of the Living Lab with the highest feasible degree of reusability.

Noteworthy supplementary outcomes of the transformation encompass the registration of the school building in Madastar and the integration of circular professional practices across the array of courses offered.

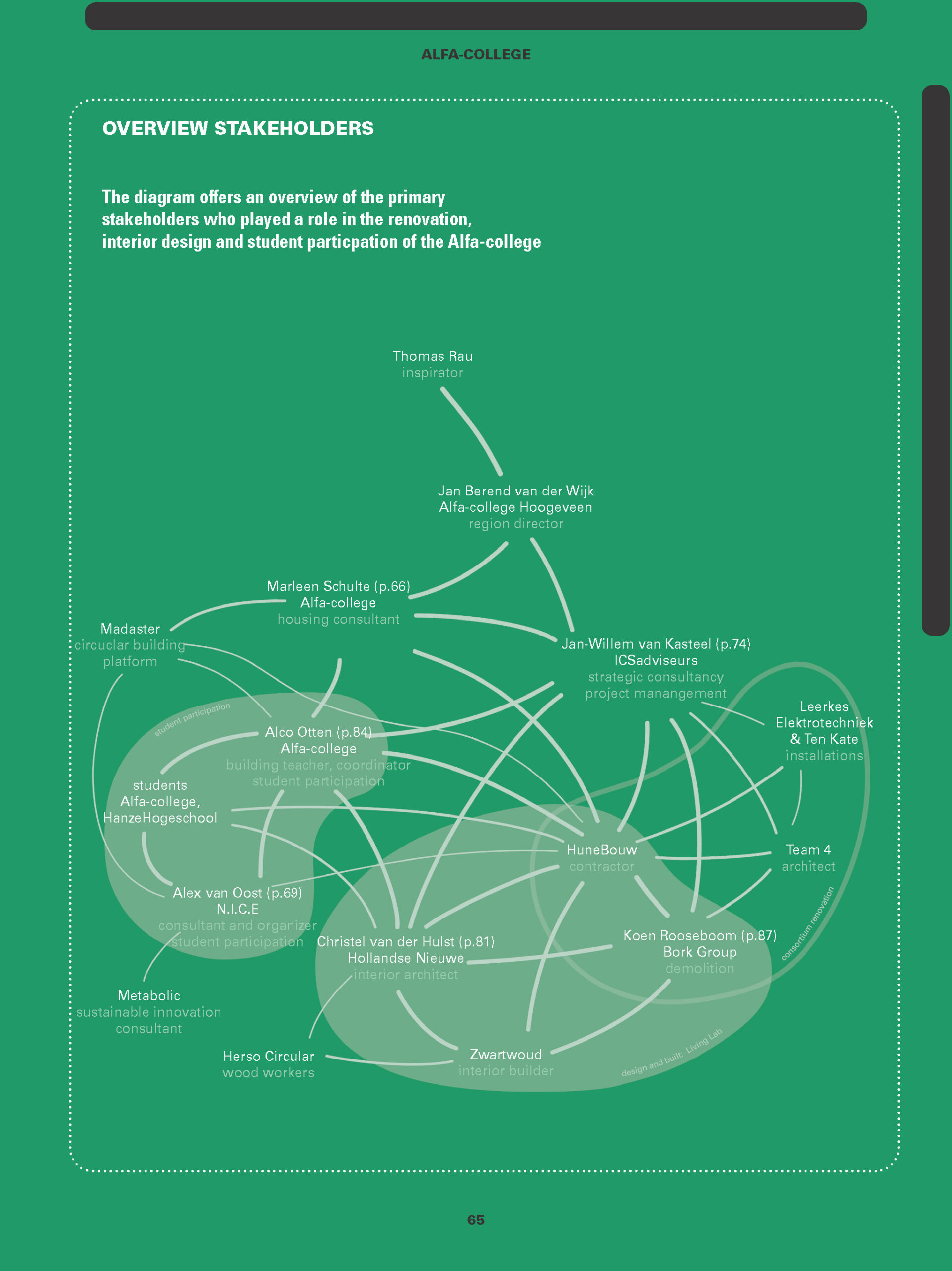

Overview Stakeholders

The following conversation with Jan-Willem van Kasteel, interviewed by Marieke van den Heuvel, is part of the exploration of the circular renovation of the Alfa-College Voltastraat.

Considerations for Renovation

ICSadviseurs guides schools in housing and building processes, within which Jan-Willem van Kasteel focuses on sustainable and circular projects. He reflects on the project:

MvdH: When is circular renovation the optimal choice?

JWvK: In principle, any building has the potential for reuse, but the key question is the overall feasibility. Structures that are forty to fifty years old often have limited materials and possibilities, this presents a challenging starting point. Having adequate ventilation in buildings has gained significant importance, particularly in the wake of COVID-19. The available clear ceiling height in relation to the dimensions of the air ducts becomes a critical factor in making modifications, and sometimes the fit is simply not feasible. Conversely, there are schools from the same era that were constructed more robustly, making them more suitable for repurposing.

If the prerequisites are met, reusing existing structures is my preference. However, financial considerations often dictate decisions. If municipalities or boards can’t allocate sufficient budgets in a timely manner, they may opt to prolong the lifespan of moderately suitable buildings due to financial constraints. In such cases, it becomes necessary to question whether starting anew and designing with future reuse in mind, thereby enabling circularity for future generations, would be a better approach. It is crucial to consider these factors at the project’s outset and evaluate them based on both cost and sustainability.

MvdH: Can we construct a school that will last longer than forty or fifty years with the knowledge and technology available today?

JWvK: The question revolves around how can we anticipate the future of education in forty years. Looking back forty years, digital education did not exist. Yet, we still find ourselves working within traditional classrooms. When it comes to real estate, decisions must be made for the long term. However, school buildings face not only functional changes but also demographic trends. I am currently involved in a project where the building is a third larger than currently needed. Unfortunately, I cannot repurpose this surplus space when there is no demand for it. That leaves no other option but to demolish part of the building, as in the case of Alfa-college.

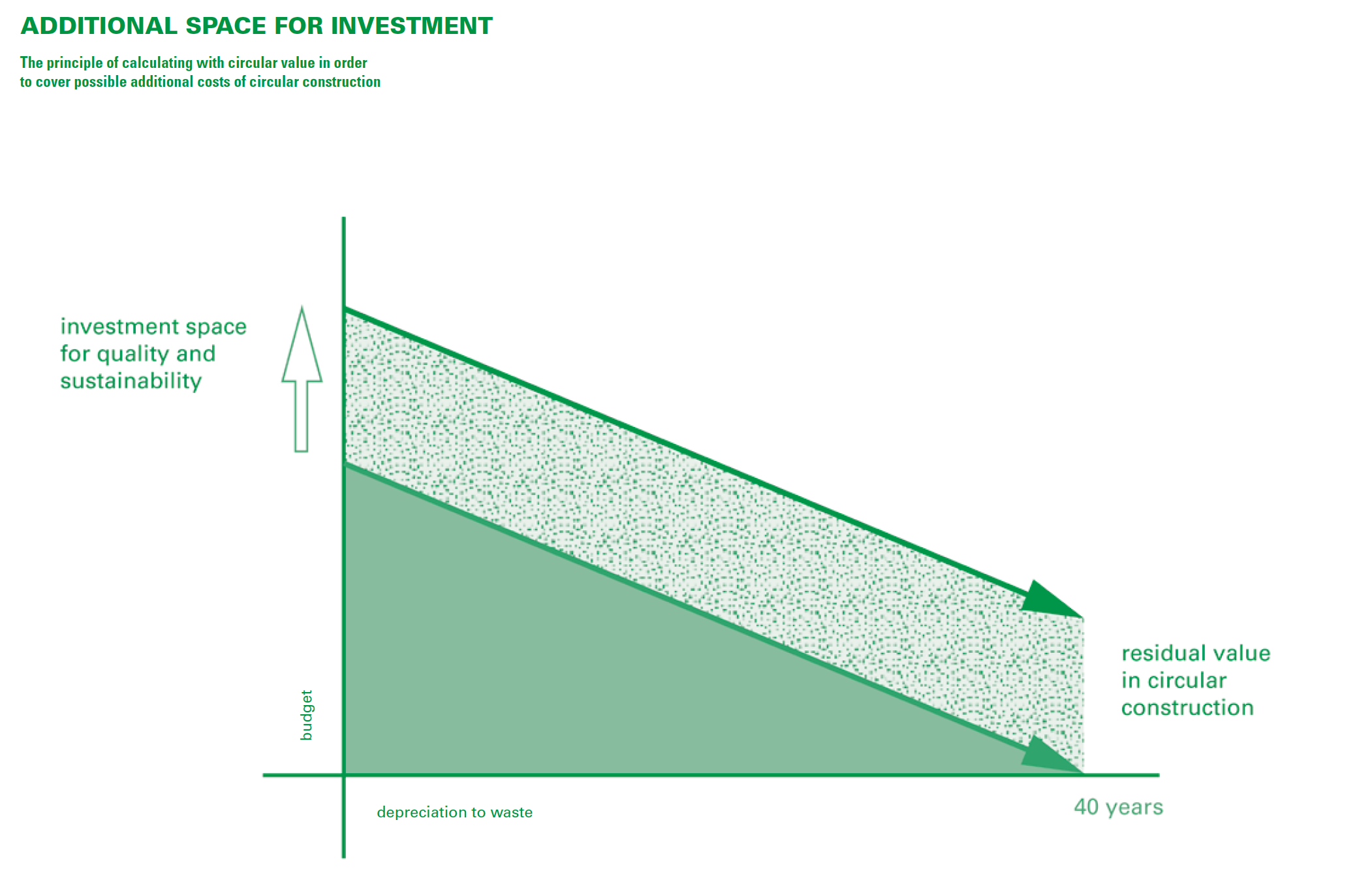

Circular construction opens up new possibilities for extending the lifespan of buildings. By designing elements for disassembly, materials retain their value and we do not have to write off the building in its entirety, but only seventy percent, for example. This thirty percent reduction in depreciation creates room in the annual cost calculation, as repayment costs decrease. The resources saved can then be redirected towards sustainable investments.

What we at ICSadviseurs are working on now is exploring how to translate residual value in circular construction not only into environmental gain, but also into financial value. While organizations like Madaster convert materials back to their raw material form, for instance, where steel needs to be ground up to create a new beam, which is then assigned a financial value, we find it more compelling to design buildings to be demountable. This allows the entire structure to be disassembled, with each individual element retained. This approach reduces production costs, energy consumption, and various other expenses. As a result, that beam retains a significantly higher value than just its raw material composition. Unfortunately, many clients still perceive this approach as overly complex because they question who will guarantee the value of these materials forty years from now?

The first step towards achieving this vision is to digitize buildings and input them into platforms like Madaster. This enables us to access information on the available materials, their dimensions, and other relevant details in the coming decades.

MvdH: That is still a long way off, how can we build circularly with reused materials?

JWvK: One of the problems we face is the limited availability of materials from demolitions to meet the current demand for building construction. This shortage arises because many buildings are not designed with disassembly in mind, hindering effective and high-grade reuse of materials. As a result, the reused materials often find application in interior projects, eye-catching features, or as storytelling elements, but this typically marks the end of their life in their current form.

MvdH: During the renovation of Alfa-college, what were the objectives and aspirations regarding circularity?

JWvK: At the start of the project, architect Thomas Rau inspired the board with his vision on circularity. This not only increased their enthusiasm for circular construction but also strengthened their conviction regarding the significance of circularity for the students. Circular practices represent the future for the new generation, as they will be responsible for shaping the Circular Economy in all its aspects.

Throughout the renovation, three key themes were established: energy efficiency, circularity, and a healthy indoor climate. Later, nature inclusive design was added due to the highly urbanized surroundings of the school. While these themes formed the foundation, they were not yet fully defined. To proceed, we initiated a Best Value tender, inviting the market’s expertise and encouraging them to present their finest proposals. Quality, rather than price, became the primary factor for comparison. HuneBouw, a local contractor with limited experience in circular construction but highly motivated, won the tender by effectively translating the energy ambition. Their focus included CO2 reduction through energy conservation, insulation, and the installation of solar panels. As the process unfolded, we collaboratively developed the remaining themes with HuneBouw and the Alfa-college.

MvdH: Have you connected specific definitions to the stated guiding principles, and have you quantified the objectives?

JWvK: To address the aspect of health, we followed the ‘Fresh Schools Class B certification’ for existing buildings. This certification focuses on noise reduction and acoustics, ventilation, optimizing lighting and daylighting, and other relevant factors. In terms of energy savings, the Alfa-college has been transformed from a building performing poorly on energy usage to a Paris-proof building. This means that the energy consumption aligns with the targets outlined in the 2015 climate agreement. Achieving this milestone required a substantial investment, and I had to approach the Supervisory Board twice to secure additional funding and convince them of the value this investment would bring.

As for circularity, we didn’t initially have a specific definition formulated. However, we gradually embraced this concept by incorporating numerous materials from the demolished building into the interior, among other measures.

MvdH: What was your role during the renovation?

JWvK: I was the project manager. Initially, this was just a few hours a week, but during the project my involvement increased significantly. A major aspect of my responsibility was to ensure that the circular ambitions were upheld. I acted as a catalyst, as it was crucial to prevent the team from resorting to conventional solutions. Within the consortium, I consistently posed questions such as: What makes this solution circular? Yes, it may save energy, but are the materials chosen renewable? Can we explore better alternatives? Initially, this approach sometimes caused friction, but as the process unfolded, the other team members began to embrace it and contribute their own ideas and alternatives. In this way, we grew and developed as a cohesive team.

MvdH: What was the experience of the consortium members with sustainable construction?

JWvK: The scope of this renovation mainly involved building-installations above the ceiling. HuneBouw had brought in a building services installer from their existing network, and our ambitious goals often clashed with the plans they had already prepared. Additionally, the market is lagging. While there is some supply of recycled tin and air ducts, the concept of circularity through reuse is still hardly present. Environmental gains could be achieved mainly through energy savings due to installation technology, however, this approach contradicted our original agreement with the client to minimize modifications to the existing installations.

MvdH: Within the consortium there was an architect engaged, Team4, in addition a separate commission was issued for the Living Lab. How was the division of labor between the two design firms?

JWvK: Team4 was responsible for the structural design, which included the spatial layout, wall finishes, floors, and ceilings. They determined the color scheme for the hallways and wrapped the doors in new colors to enable repurposing. In order to achieve a healthy indoor climate, large shafts were created in the corridor to accommodate ventilation ducts. They lined the shafts with reused slats from the ceiling of the demolished building.

Hollandse Nieuwe, on the other hand, was in charge of designing the Living Lab. The Living Lab showcases vocational education within the school, so you can see the cooks cooking, the hairdressers cutting hair, and the construction workers laying bricks. The Living Lab is located around the central cafeteria, and Hollandse Nieuwe proposed ideas to enhance transparency and openness. However, these proposals sparked serious discussions among the different parties due to their major construction implications. Fortunately, in the end, it was successful as it resulted in an improved spatial experience.

The next step involved identifying materials suitable for reuse. Wall panels and window frames from the demolished section of the building were utilized to create the different spaces on the learning plaza. This is when you realize how difficult circularity is in practice. Initially, we thought the window frames were of high quality, but upon disassembly, we discovered they were simple wooden beams with slats sandwiching the glass. Despite their basic construction quality, we were still able to reuse them.

MvdH: How circular is the renovation of Alfa-college?

JWvK: We have made as many circular choices as possible, such as using EPS beads in the cavity walls instead of polyurethane foam (PUR) insulation, allowing for easy removal of the insulation in the future. However, looking at the overall effort, the project falls short of being the most circular renovation achievable. NICE obtained data from the contractor and collaborated with college students to map out material flows. They worked with sustainability consultant Metabolic to conduct a raw material flow analysis, which was then represented in a diagram illustrating the inflow and outflow of all raw materials in the building. It is noteworthy that a significant portion of the materials removed fell into the categories of ‘recycle’ (39%) and ‘recover’ (34%). The ‘recover’ category involves incineration or landfilling, which is the least desirable option, but even recycling often leads to a form of downcycling. This means that more than half of the materials released were reused in a low-grade manner.

By establishing transparent resource flows early in the process, we were able to seek ways to improve our outcomes throughout the remainder of the project. The Living Lab’s interior demonstrated the most successful application of circularity, as many materials were directly reclaimed from the demolished building and repurposed for that specific purpose. This achievement is significant because interiors often have a high turnover rate where the aesthetic lifespan is much shorter than the functional one, making them less sustainable than the rest of the building.

MvdH: Has the circular renovation of Alfa-college influenced your sustainability strategy?

JWvK: It highlighted the importance of continuous innovation in our approach to circularity. One notable improvement is the continuous collaboration between ICSadvisors on Madaster. As a result, we integrated their materials passport demands as a standard component in our contracts, and we require every architect we collaborate with to submit this data accordingly. As project managers and housing providers, we firmly believe that this practice represents the future.

Complete access to the preceding conversations on Alfa-College, and more insights on circular interior design in VOLUME63, THE NOT-SO-EASY GUIDE TO CIRCULAR INTERIOR DESIGN.