Borrowed Scenery: In the Footsteps of Laurie Anderson

Thomas Daniell

These days I love looking up at huge oak trees and watching the way the branches stand out against the sky. That to me can take up the whole day. Kind of like when I was a child. I’m finding that the sky and weather and animals have a new fascination to me. If you’d asked about nature or the outdoors five years ago, I would’ve just thought, ‘that’s pathetic!’ I was more interested in situations and solutions, and technology. Now I’m going in another direction. What direction is it? Well, I’m improvising.

Laurie Anderson

At the most abstract level, the task for the artist and for the architect is essentially the same: to specify a frame. The artist’s frame may be entirely concrete or entirely abstract – from an ornately gilded rectangle to a spoken instruction – but always acts to define its contents as being artworks, whether they are newly created or nothing but found objects. The architect typically frames spaces and their interrelationships by means of architectonic elements – walls and windows – but there are some (Cedric Price, Bernard Tschumi) who are more interested in using an absolute minimum of physical intervention to enable spatial configurations and patterns of activity, or even eliminating the building altogether. This view of architecture as being fundamentally an art of organization – an attempt to dilute its physical presence while simultaneously expanding its palette to include intangible, temporal elements – intersects with those genres of art that encompass inhabitable spaces, multimedia, performance, and responsive environments.

For several decades now, Laurie Anderson’s body of work has been an ongoing challenge to the artistic frame, its permissible contents, and the definition of art itself. Omnivorously incorporating the materials and memes of contemporary life and modern technology into a bricolage of images, sounds, movements, and spaces, her work reframes and juxtaposes aspects of the world to reveal unexpected affiliations and resonances, humor and beauty. Although only present in person for a two-day series of concerts, Anderson’s semi-permanent contribution to Expo 2005 (Aichi, Japan, March 25–September 25) is a large-scale, outdoor project entitled Walk. It comprises a series of installations along a path she has chosen, winding through a 7-hectare Japanese garden on the Expo grounds. Visitors are given a map drawn by Anderson indicating the route to be taken and the events that will unfold along the way. This is performance art by proxy: a loose script for the audience to follow as they move through an existing landscape that has been edited and enhanced by the artist.

The traditional Japanese stroll garden is itself already a fully designed environment; its apparent spontaneity is actually a contrived amplification of nature, every scene considered and composed. Anderson has superimposed her own narrative on this backdrop, providing sounds and images that subtly control the movements and viewpoints of visitors. Signs along the path indicate when to pause and use the MP3 player provided to listen (with headphones) to each of the six musical pieces she has composed for the garden – nature-themed ambient soundscapes of instruments and voices, recorded in three-dimensional binaural sound. Each visitor is also given a small sound-receiver made of bamboo called an Aimulet, a new technology that uses spherical solar cells to pick up sounds converted into infrared radiation, audible only when the device is held to the ear and precisely oriented toward the sound source. There are two Aimulet sites in the garden, both of which broadcast multiple, simultaneous soundtracks: one gives greetings in several languages (Chinese, Japanese, French, English), the other overlapping pieces of music.

Most of Anderson’s interventions in the garden are similarly reliant on being in very specific positions: at the Tiger-in-the-Trees, for example, dispersed line fragments coalesce into the image of a tiger at only one particular viewing angle; the Turtle Bridge is embedded with weight sensors that trigger prerecorded gong sounds according to where people stand. Translation, and its potential ambiguity, is a theme that reappears throughout Anderson’s work, whether between different sensory experiences – physical movements with corresponding sounds and images – or between languages. In the Wordfall installation, located in a small pavilion in the garden, Japanese script slides down an LED panel into a pool of water, at which point a concealed video projector instantaneously replaces it with an English translation that floats away and vanishes.

The Walk is of course far more than the sum total of these installations. Existing in a synergistic relationship with the garden itself, and the wider environment of climatic and seasonal change, Anderson’s project is somehow analogous with shakkei (“borrowed scenery”), a Japanese landscape gardening technique that involves incorporating elements of the surrounding landscape within a local composition, framing and taming aspects of the world outside your direct control. Anderson has here extracted and distilled a path from an existing territory, and just like shakkei, its success is dependent on being able to control the viewer’s location and sightlines.

Indeed, the Walk may be participatory, but it is not ‘interactive’ in the trivial sense of much media art; Anderson has often stated her preference for artworks that are complete, fully specified according to the artist’s intentions. Although without Anderson present to enact the performance and tell the story (the MP3 player soundtrack does occasionally provide her beautifully modulated voice, with its impeccable phrasing and perfectly timed pauses), we still have clear instructions to follow.

Leaving her studio for the great outdoors was apparently less a choice than a necessary escape: “I’ve been trying very hard in the last two years to get away from computers and from staring at rectangles, and thinking that actually things can be crammed into that little shape […] I decided to do everything outside. I was burning out on those screens, I just could not do it another second. That’s why I’m doing this garden project in Japan.”

There is a feeling of relief and calm in the work, partly due to the absence of Anderson’s usual wry comments, surreal anecdotes, and disquieting observations, and partly due to the obvious pleasure she takes in the beauty of the garden itself. Unconfined by the studio or the stage, the work is in a sense even more architectural, defining an environment and the activities it contains with the lightest of touches. The specific interventions are just a way of getting us to slow down and pay closer attention as we walk through the garden: to enjoy the details, to take our time, and to experience it all (as she says) in the present tense.

Walk Credits:

Written and Directed by Laurie Anderson – Original Score by Laurie Anderson

Produced by Cheryl Kaplan – Sound design by Jody Elff

Aimulet installations designed by Laurie Anderson with Hideo Itoh / AIST Labs, Japan

Japanese Garden designed by Masayuki Wakui

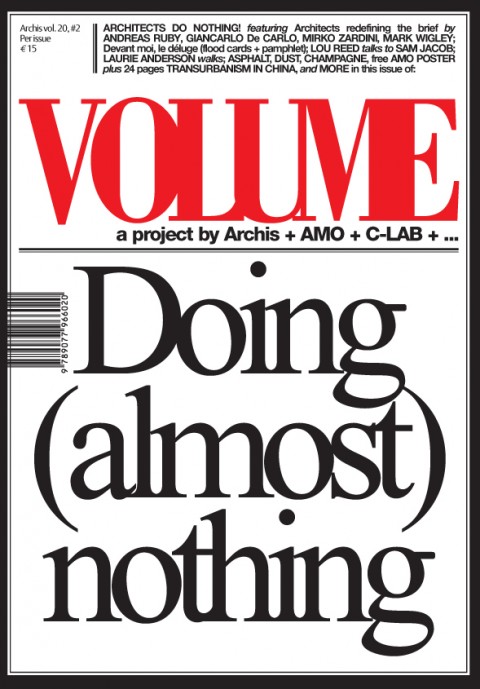

This article is part of Volume #2, ‘Doing (Almost) Nothing’.

This article is part of Volume #2, ‘Doing (Almost) Nothing’.