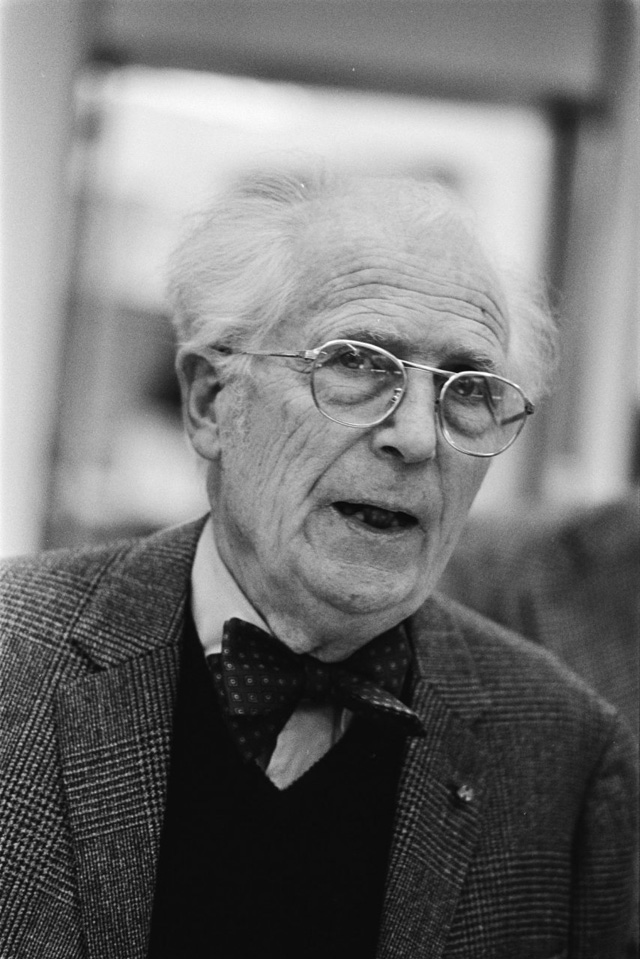

Alexander Bodon (1906-1993)

Bodon was born in Hungary. His father was an interior designer and cabinet-maker who worked in Jugendstil and was influenced by the Viennese Secession. At the age of thirteen Bodon spent some time in the Netherlands and by chance was introduced to humanist circles where he met Jan Wils. When in 1926 Bodon had to acquire practical experience as part of his studies the obvious step was for him to go to the Netherlands and study under Wils.

This proved to be an experience for the young Hungarian because through Wils he got to know V. Huszár and C. van Eesteren, who were both directly involved in De Stijl. `It was as if I had discovered a new civilization,’ he was to say later. After this second period in the Netherlands he found he could no longer settle in his native country, where architecture was still dominated by Hungarian Baroque. So in 1929 he returned to the Netherlands, this time for good.

He worked for a while for J.W.E. Buijs and J.B. Lürsen (where one of his projects was the offices of the Arbeiderspers publishing house in Amsterdam) and soon afterwards he independently designed the Schröder and Dupont bookshop (1932), thus becoming known as being in sympathy with the young Dutch Moderns. J. Duiker and B. Merkelbach took him into their circle and Bodon became a member of the `De 8′ group of architects. From 1934 onwards he worked with Merkelbach and C. Karsten (one project being the AVRO broadcasting studio in Hilversum) and at that time headed the interior design department at the Nieuwe Kunstschool in Amsterdam, which was modelled on the Bauhaus. In 1939 Bodon became a Dutch citizen.

After the war the reconstruction brought housing commissions, but Bodon’s career did not really take off until 1960 when he secured the commission for a new exhibition hall for the RAI in Amsterdam (additional commissions for this project were to follow until his death). Most of the work that was done later was credited to the DSBV office, consisting of Bodon and several partners.

Describing Bodon’s buildings means thinking in terms such as chic, proper and well-made. His architecture stays close to the problem and reveals an innate interest in technique. Though never innovative, his work was deeply indebted to the achiuevement of the twentieth century. In the thirties he contributed to developments in architecture enthusiastically, spontaneously and directly through several small projects, and he was inspired by his colleagues in `De 8 en Opbouw’. His postwar work is not only more substantial but also in a sense more individual since Bodon was one of the few architects who managed to avoid the bleakness into which the modern vocabulary seemed to lapse in the postwar period.

He undoubtedly won himself a place in history, primarily with the Schröder and Dupont bookshop and the RAI exhibition hall. But these two projects must not be allowed to conceal the fact that there is more: for example, the `De Leperkoen’ house (Lunteren, 1948), with its stimulating dialogue between shade and light, and the Hoogovens training centre (IJmuiden, 1966), with its masterly ordering and natural unity in form and construction.

When we were working together, just a few years ago, on the monograph about his work, Bodon and I found we agreed that a good building should be as exciting and harmonious as a piece by Bach, as alluring as a beautiful woman, and as compelling as the movement of a yacht in a fresh breeze, force 5 or 6. Bodon’s best work meets these criteria.