The Cycle of Japan is an ongoing lecture series at the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam that is exploring what the Netherlands can learn from Japanese urban practice. Edwin Gardner kicked off the series with a talk on February 14th. His lecture was a deeply poetic and psychogeographic meditation on the nature of cyclical time in Tokyo, and its effect on the city’s built environment.

Edwin Gardner is a theorist, architect and cofounder of Monnik, a Dutch research collective. He was in Tokyo to put together Still City, an alternative guide to the city. There, he met and did workshops with various artists, designers, and other urban explorers during a mentally stimulating and physically exhausting two-month stay.

Gardner presented his thoughts in the style of retrospective diary entries. Like his meditations on Tokyo, the entries were presented non-chronologically. He began by establishing the familiar. In the Netherlands, and the West in general, there is a notion that progress is equal to growth: an increase of buildings, of cities, of developed square metres. This means that in crisis, expansion mechanisms come to a halt, and the economy is effectively paralyzed.

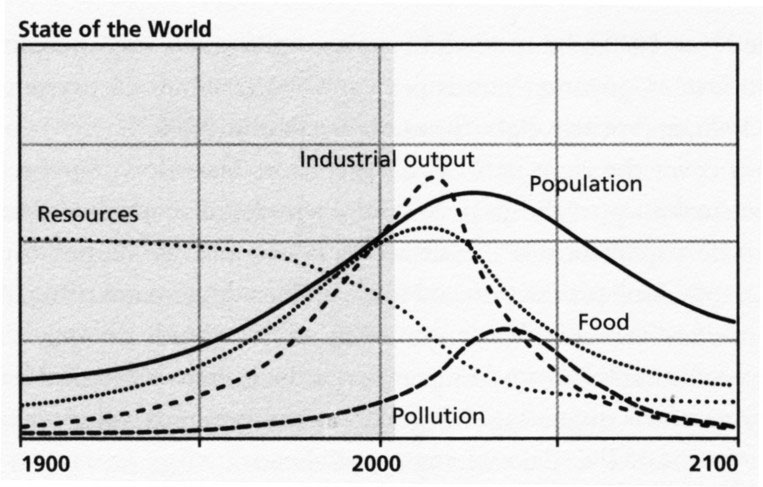

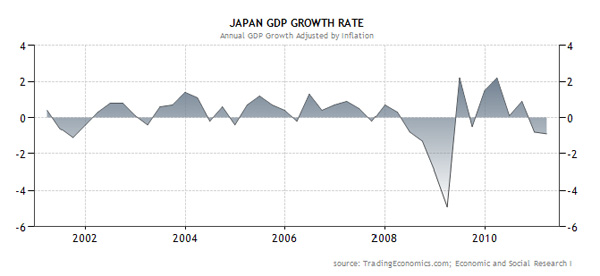

In Japan there is more of a cyclic notion of growth. Construction and demolition, growth and non-growth are essential elements of the same structure. As its economy has not experienced growth for two decades, Japan is indeed a post-growth urban society. The country is in fact demographically shrinking.

The idea of cyclic time in Japan versus linear in the West is conceptually clear, but is hard to grasp and apply to the realm of the pragmatic. Instead, we quickly get to deep philosophical meditations on space and time that are very interesting, but not too useful. Gardner puts it straight: “Tokyo doesn’t grow or shrink. But what does that mean?”

Before delving into Tokyo, Gardner brought us back to the Netherlands, where space and time are more stable. Generally, Western cities are essentially timelines. The progression of medieval, organic and compact centres, followed by more organized expansions of inner city suburbs, with newer ones surrounding those, followed by 1960s modernist towers and American-style suburbs in the periphery root us in a linear progression of stable time as expressed in space.

This type of stability is not present in cyclical Tokyo, as reflected in the city’s built form.

Using a variety of examples, Gardner demonstrated instances of cyclical time in Japan’s biggest city. For one, the average age of a person in Tokyo is 40, while the average age of a building is 26: people live to see their city change. Gardner explains that this is because the Japanese put more emphasis on the land itself, rather than the buildings on the land. Houses are treated like cars. The newer they are, the more valuable. With use, their value depreciates. Houses are built with their demolition written into their contracts. Therefore, there is constant re-building. In Tokyo, there are temples that are younger than communications towers. This recurrence of things, rather than a linear progression in space, provides stability.

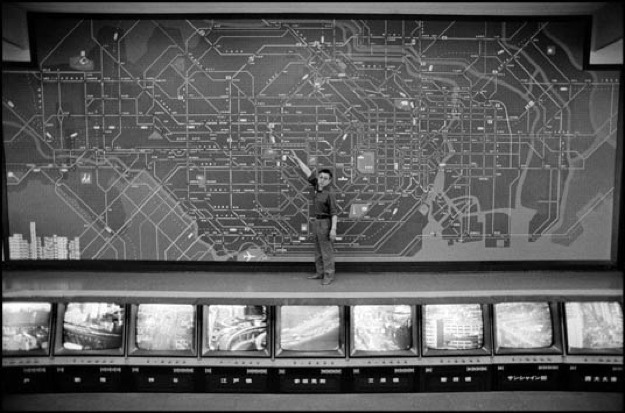

Gardner’s lecture was enhanced by the simultaneous presentation of large-format aerial footage of Tokyo. The footage is hypnotic, panning over the city’s endless horizons and periodically focusing on specific buildings, monuments, and intersections. Tokyo is enormous. A city within a metropolitan region of 35 million, 4 hour commutes are common. The undulating aerial views illustrated both the enormity of the place, and the difficulty of grasping the concept of a city that is constantly rebuilding itself in endless growth and decay. Tokyo, abuzz with traffic, appears otherwise motionless. It is a city that is simultaneously still and dynamic, “a starry sky, twinkling/a city of continuously regenerating cells”.

In terms of cyclical time’s application to economic and architectural pragmatism, Tokyo’s low average building age and constant de/re-construction translates to a housing market that can quickly react to demographic shifts. Recently, there has been a rise in households comprised of singles and couples with no children. These two categories currently make up 40% of Tokyo’s population. As a result, the demand for apartments under 20 square metres has risen. The city of simultaneous growth and decay provides a built environment that can quickly adapt to reflect this new demographic reality.

While the lecture was a deeply engaging, poetic and psychogeographic meditation on time and space in Japan, it provided relatively few practical examples of how the Netherlands can learn from Japanese urban practice.

Gardner’s talk, however, provided the space for a deep (re)consideration of how our notions of time and space effect our cities and our economies. To widely acknowledge the possibility of simultaneous growth and non-growth is the first step in include it into our consciousness and practices as we continue to build and densify cities in the Netherlands. The notion of a functioning economy, despite crisis, is also powerful. (Despite official positions, you’ll know this intuitively in cultural scenes’ abilities to thrive within times of economic trouble.)

Gardner also referenced the concept of the ‘circular economy’, and the challenge of our society’s transition toward that model. The circular economy reflects a natural system that reuses its waste and values diversity. There is no “end” of a product’s life cycle, rather a constant reuse of materials – the cradle to cradle model.

To be clear, establishing a circular economy would not be a case of simply adopting the Japanese notion of cyclical time. It is a radical economic transformation that would mean a shift from dependence on fossil fuels toward renewable energy, a transition that Japan, despite its cyclical notion of time, has also not made huge advancements with.

Be sure to join us at the next installment of the Capita Selecta Cycle of Japan Series on February 21st for Moriko Kira’s lecture and more in-depth investigations of Japanese urbanism and its application to the Netherlands. The lectures are open to the public and take place at the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam, Waterlooplein 213. All lectures are in English and start at 20:00. Admission is free.