It’s shortly after the opening of UABB/SZ 2017 that I have an appointment with Liu Xiaodu, member of the curatorial team (together with his partner at Urbanus, Meng Yan, and famous art curator, Hou Hanru). We meet in the temporary library of the UABB, a space to sit and read about contributors and their contributions to this seventh iteration. His biennial is dedicated to the quality of diversity; Cities, Grow in Difference, it’s called. I explain that Volume is working on the theme of technology as a push factor in the spatial and social arrangements of our society and what role architectural design and the designer could have. As well as the divide between ‘coders’ and architects. It hits a sweet spot in Liu Xiaodu.

Liu Xiaodu: Science, technology, … When I talk to these technical guys, I just feel that they don’t have a humanitarian view or understanding of what they’re doing. What does a human really want and need? They’re fascinated with what is possible, what they can create. Computer generated stuff, artificial intelligence etc.; it’s fascinating of course. But they don’t think about how it’s going to be used or the dangers of that thing running out of control. It’s very Chinese to be optimistic about the future. Even when the environment is falling apart they think tomorrow will be better.

Arjen Oosterman: Does that include accepting new technologies?

LXD: ‘New’ means ‘good’. As simple as that. That’s deeply embedded in the Chinese people’s mind, I think. New is good, the future is good, children are good, of course! [laughs] They don’t have this western, more suspicious, critical relation with the ‘new’. If something new is introduced in China, people want to test it and use it. Something like WeChat wouldn’t happen in the West. In only a couple of months, the number of users exploded from a couple of thousand to twenty million and now everybody is using it. They don’t care too much about their privacy, because they know that they don’t have privacy anyway. The Chinese have a very public/social lifestyle. Everybody knows everything about everybody.

AO: Is this embracing of the future something you question in this event, in relation to the urban village as a starting point? Embracing the future usually comes with demolition and replacement.

LXD: Yes, exactly. A lot of my friends feel economy to be number one and whatever happens to the urban village is the right of its owners and that they have the right to become rich. And if this implies demolition, so be it. I clearly don’t agree with that idea. So we had fights. At first the villagers thought we’re more naive; scholars, intellectuals; not practical. It’s typical (that attitude) in the government, in real estate, in the world of technology and even among architects. And also the majority people in Shenzhen, they don’t really know the urban villages. They feel the urban village should be demolished. They think it’s a place of crime, prostitution, dirt, pollution, and that the people there live like rats. There are also people that say the opposite: keep it as is, don’t intervene! They say that we, as architects, are busy making our fame, not doing anything real for the tenants in these villages.

But a lot of people support us, more and more actually. After this biennale a lot people will have changed their opinion. That is what we’re after. I think that the humanitarian right to a better life is what we all agree on. A good city is not a city that says everybody should live in the same type of apartment, that everybody is the same. That is not a good society. A good city is when people are coming, migrating, that they have hope to improve themselves and change their lives, no matter if they start from a very low position. If the city allows people to do that, it is a good city.

During the opening symposium, a lady expressed her feelings about the urban village in an impressive way. She said: “I’m from the countryside, I moved to the city to change my life. I found that the urban village is the place I can really stay.” For her and her family the urban village was characterized by three aspects/notions: Firstly, it is her hospital. Her younger brother was a drug addict in the village she came from. So, she brought him to Shenzhen to the rehab. And another family member was depressed and suicidal. And she brought her to the urban village as well. And being surrounded by a lot of people and attention, she sort of recovered. So, curing her family members was a first incentive to come to Shenzhen and the urban village. And because she can make a living there, she can feed her family. And secondly, it is a lodge. She said: “I’m not going to stay here forever, I will return to my own village in the countryside, that is my real home. But here I stay and although people say the urban village is filthy, it is much cleaner than villages in the countryside.” And thirdly, the urban village is a library. When her mother came over as well, a very traditional woman with strict ideas, her eyes were opened, confronted by all these new things. She learned a lot, for instance to use WeChat to pay. So, when she returned to her home town, she became a very respected older lady. It changed the person.

I was touched by this story. The urban village provides a kind of hope, the countryside cannot.

What we are doing is valuable. Such a story gives me the confidence that we’re on the right track.

AO: Does the urban village act as an emancipation machine then?

LXD: Quite so.

AO: What is the difference with living in the regular city?

LX: Everybody wants to live in the regular city, people think that is much nicer. But the reality in Chinese cities is… Look, twenty million people are living on this tiny strip of land along the border; that is not enough. Maybe 10 million of them live in urban villages, or in comparable conditions like row-houses. They are living in a super dense area. It is the only way we can cope with these 10 million. Of course, we should give them better living conditions, improve their situation. But is demolishing these neighborhoods and replacing them with high rises the solution? That is unaffordable for most people, even for me. If you get rid of the village, the people living there are gone. They simply won’t have a place to stay. Consider that an urban village houses maybe 100,000 tenants, whereas the original village had 2,000 inhabitants (now the owners of the urban village). 95% or 98% are immigrants. And they will be pushed out, either back to their home villages or to the fringes of the city. Most will go to the suburbs and will have to commute for hours to reach their work. Think of the amount of public transportation that it would require. Now they walk or ride a bicycle. Then they would need to spend 500 Yuan each month on transportation alone. And the city is already very congested. So, if you don’t have a solution for such issues, stop tearing down such neighborhoods. Now the situation is somewhat balanced.

And also consider that we don’t have enough laborers for the growing economy, and we need those people: waitresses, cleaning ladies. If we push them out everybody will have to pay more, because costs for everyone will increase.

space design by Atelier Bow-Wow. Photo: Zang Chao

AO: Wiping away and replacing with high rise is not the solution, clearly.

LX: Though people still think it is!

AO: Yes, but you say now: stop, take a step back, investigate, let’s try to properly understand what we’re dealing with. You want to create awareness. But you’re not only a curator, you are also an architect. What do you propose as next step?

LX: In 2005, we already published a book on the urban village in which we presented several design proposals on how to improve. Of course, that was more academic and people said it didn’t ‘come to the ground’ and wouldn’t work. But it is not that difficult to upgrade what’s here, to create somewhat better conditions: fire safety, proper ventilation, better sewerage, basics amenities. The government is willing to put money in. Everything is ready. And there is a high demand from the central government and also the local government to provide a certain percentage of social housing every year. And Shenzhen is far behind in that scheme, it doesn’t own much land. So, to convert urban villages into social housing helps. A win-win situation. Even temporarily, maybe for ten, fifteen years and leave it to the future to further decide. It gives us time to consider what we really want. To me that is the way to go.

And I see that the different parties involved are coming closer to this kind of thinking.

AO: Can you briefly indicate for those that haven’t seen the show what you confront us with?

LX: First of all, diversity. Respect people with different ideas and different lifestyles. A wake-up call. And for the visitor to experience that things can happen in the urban village. Like eight exhibitions. After the exhibition the former factory buildings we’re in now can turn into a creative hub or incubator space for startups. It’ll create job opportunities for people living here as well. The place has a lot to offer, as an anchor. We’ll also monitor what will happen with this place after the biennale.

AO: And what do you say to people who think this a very romantic idea of the urban village?

LX: It is not! We know exactly what is going on. We’re architects and we do an architecture-urbanism exhibition, we don’t pretend to solve politically the social problem in one go. But although we enter from the architecture-urbanism angle, this will trigger some other elements. We bring sociologists here, political scientists, economists and show them the issues and hear their advice. This is a start. Someone has to do it. And I really believe that people like us are the only ones that can kick off such development. Sociologists and economists are too far removed to do it.

We see it as a test ground, to show possibilities and experiment with solutions. And push towards a real kind of urban renewal. It’ll bring gentrification, but that in itself is not a bad thing. Because the pressure is enormous. Capital is looking at these spots and if the urban villages do not get stronger, they’ll be swallowed. Gentrification is an unavoidable process in current city development, but if it goes too fast, that is a problem. We should slow down that process and have a more mixed population of low and higher income. That is the better way.

We try to make this an uplifting event to create the impression that this urban village has a reason to stay and survive.

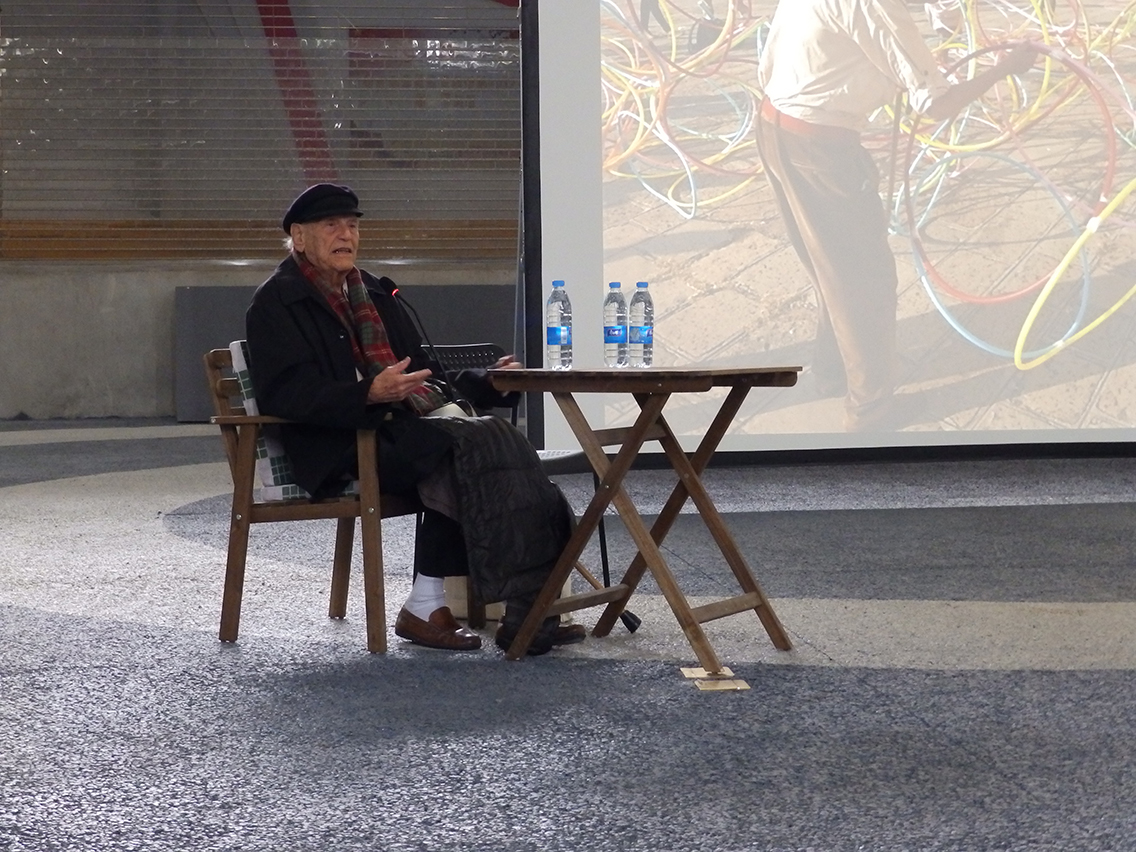

December 16, 2017. Photo: Arjen Oosterman

AO: With the urban village we’re looking at a very specific condition in China. There may be other urban fabrics in the world that compare (and you included some in your exhibition), but the way those came into existence was completely different. So, what in this exhibition that can be taken home to other countries, locations and societies?

LX: The situation here is pretty complex and that is what’s so interesting about it. It’s so energetic, something that is completely missing in gated communities for instance. That is what we have to study and understand. How people create their own living space. And we use aspects of the urban village in our own projects. For a high-end development that’ll open next year we used an urban village like mix, but we told the developer that it is a European town type. [smiles] Scale is key in that respect. And it is very successful, renters are queuing up.

AO: And do you think that the urban village is culture specific, could you apply ‘the recipe’ to an assignment in the US or in Europe?

LX: Of course. The improved, better designed version currently is. We know exactly what the problems are and how to avoid them.