In the hierarchy of major themes that shaped the modern spirit in architecture, hygiene, the imperative of a more salubrious habitat and city, is undeniably at the top of the list. With the book X-Ray Architecture (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2018), Beatriz Colomina, historian and theoretician of architecture and teacher at Princeton, chooses to make this a structuring principle, more to do with the fear of death and the repressed unconscious than the spirit of innovation. Is modern architecture as hysterical as that of the Baroque period?

Les Musiciens du Ciel, a film directed by Georges Lacombe just before the 1940 defeat of France, is an unexpected archive of a building that would no longer be the same at the end of the Second World War: the Cité de refuge, Le Corbusier’s first major work in Paris. It was also the first hermetically sealed residential building, with a glass facade without openings of 1,000 m2. Michèle Morgan plays the role of a volunteer from the Salvation Army who saves a Parisian hoodlum before succumbing to an illness never named, but which makes her cough a lot. The film includes several minutes shot in front of and especially inside the building, damaged by the bombing of the Gare d’Austerlitz. The wasting away of the heroine creates the conditions for a Christian melodrama in which self-denial and self-sacrifice triumph. In the background another story is woven: that of an implicit link between tuberculosis and the modern environment of the institution the uniform of which she wears.

Repressed trauma

If Beatriz Colomina doesn’t evoke this film to illustrate the link between pathology and architectural form that her latest work seeks to relate, it nevertheless multiplies perfectly enlightening examples. X-Ray Architecture is full of examples of the influence of tuberculosis in the emergence of the modern movement. Architecture would indeed be one of the main areas in which the fear of this contagious disease is reflected. Colomina draws a parallel between an architectural language and a sanitary obsession that was truly structuring and, a fortiori, renewable.

From the first Swiss sanatoria to the generalization of the cult of transparency in the style of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the anti-bacterial neurosis thus appears to have presided over the invention of pure forms in architecture. The book recalls, sometimes with humor, the sanitary origin of certain modern principles. The cult of white and the use of tubular steel were hospital usages before becoming marks of good taste. But her analysis also pushes the correlation into the most private spheres. The bacterial phobia would not be a determination among others, but the primordial obsession that would direct modernity towards its fulfillment, well after its emergence.

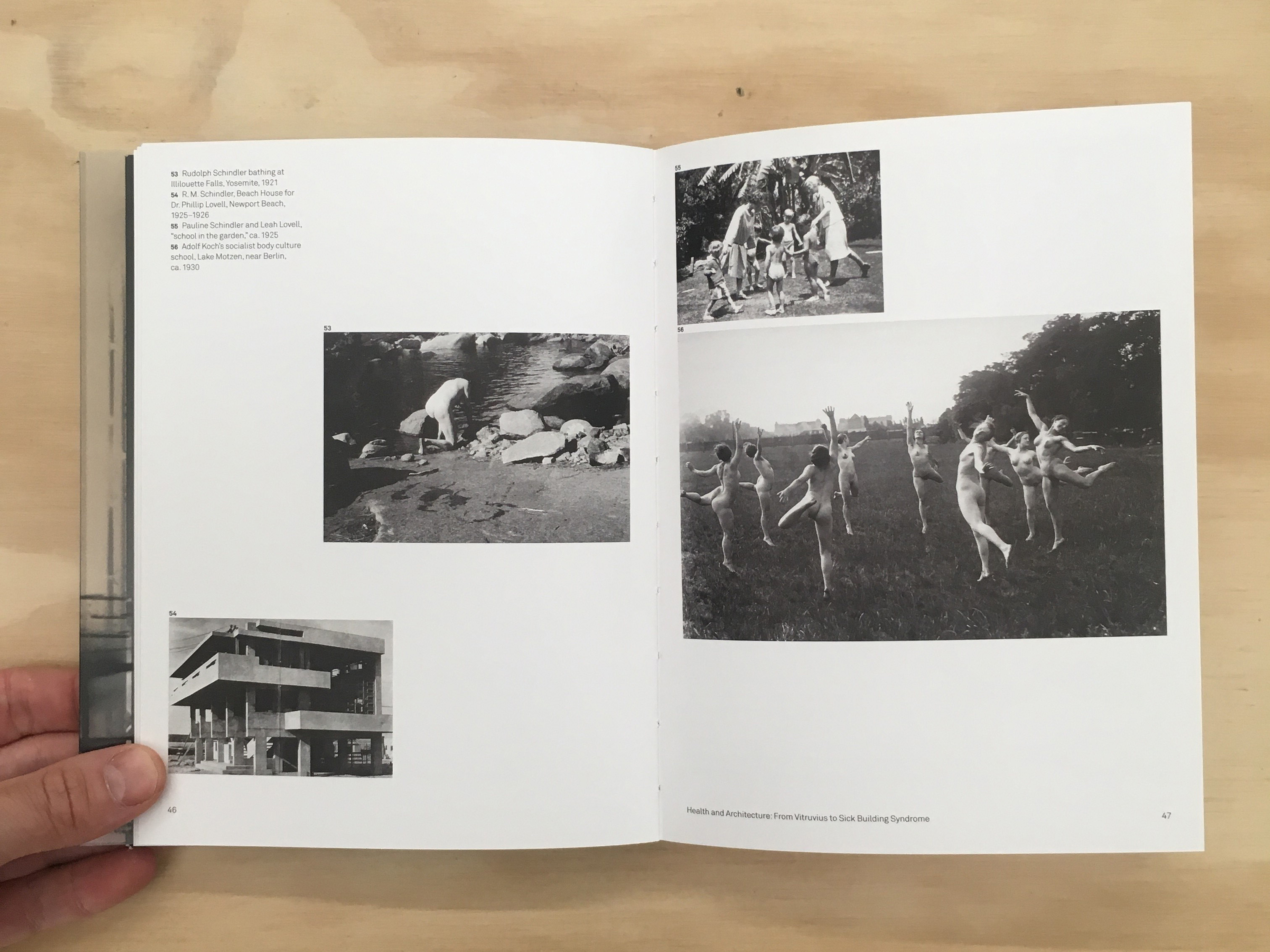

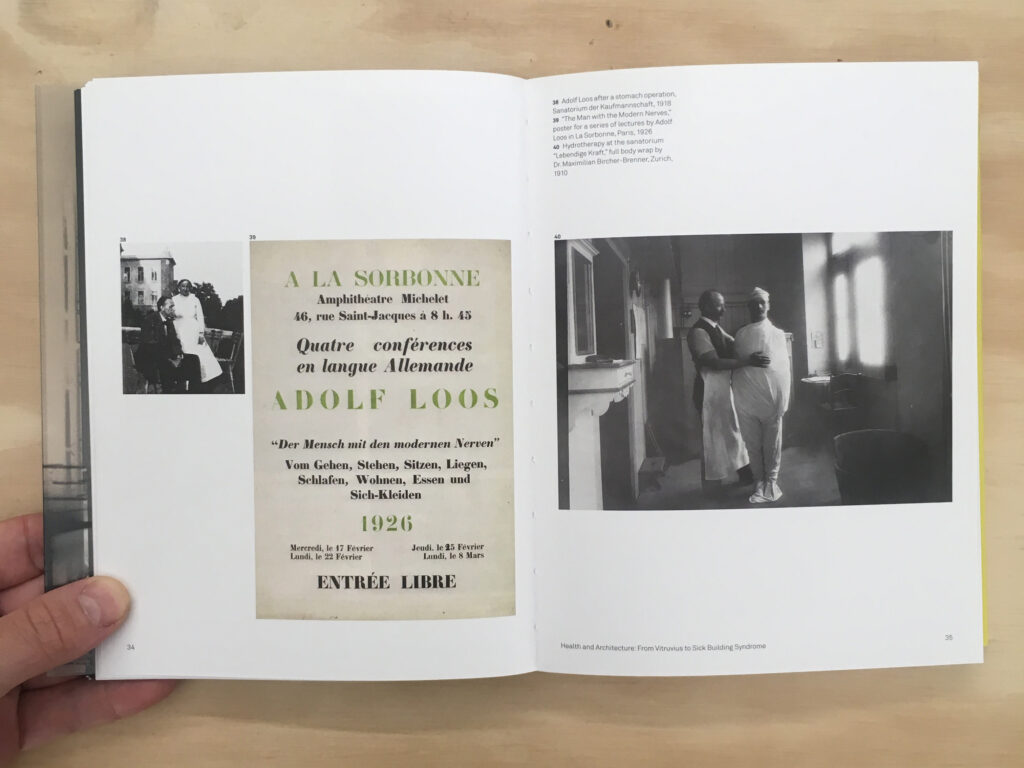

What initially appeared as a simple collective neurosis gradually became a repressed trauma, with ever-increasing influence because never explained. Colomina here takes on the role of the psychoanalyst who patiently reveals the extent of denial and its consequences. She scrutinizes semantic and iconographic shifts among the pioneers of modernity. By laying them one after the other on the couch, she thus reveals in individual paths the valetudinarian behavior that apparently conditioned their own relation to construction: Charles and Ray Eames and their orthopedic finds, Le Corbusier and the cult of the body, well-being in the style of a Californian guru with Richard Neutra, and neurological balance with Adolf Loos. Through the touching anecdote about the architect who creates under the influence of their own hypochondria, it is the medico-psychiatric reverse angle of architectural tendencies that is exposed.

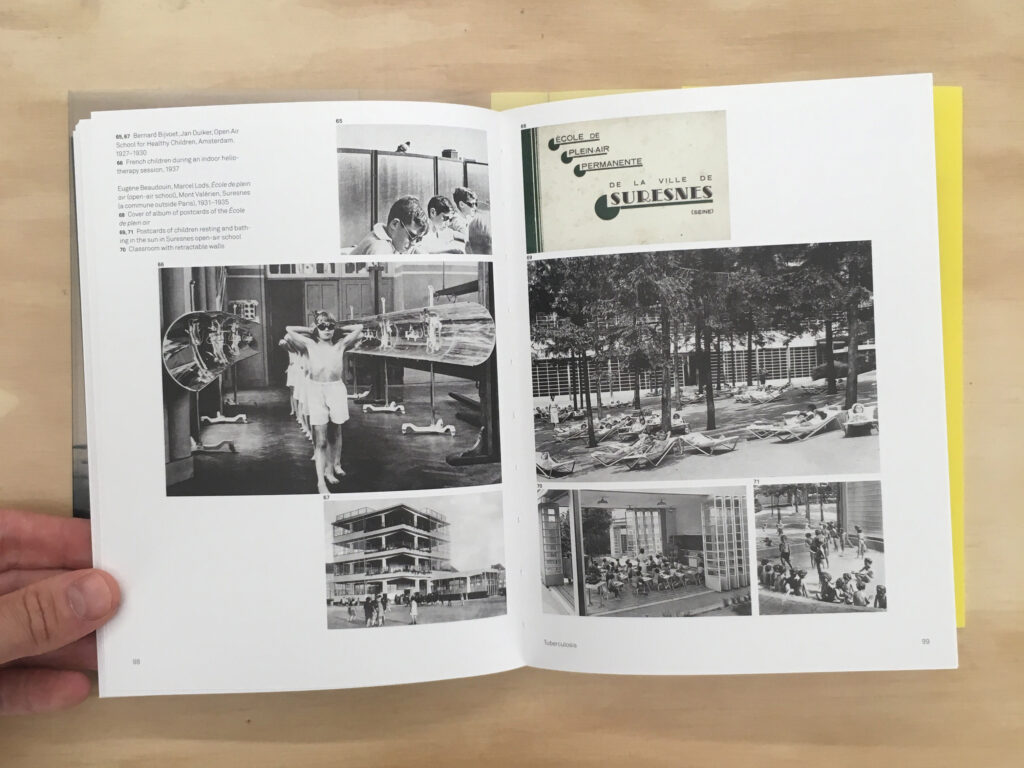

The contagious nature of this disease of bacterial origin imposed the removal of the infected subjects. In Paris, at its peak tuberculosis was the cause of one in three deaths. While the principle of keeping patients at a distance did preserve those around them, the care given to tuberculosis patients during their treatment – exposure to fresh air and sunshine – showed a lack of knowledge and an inability to act on the real causes of the disease. In the grip of analogical reasoning, the treatment sought to cure patients by exposing them to a healthy environment; it was this hypothesis that led to the rise of the number of sanatoriums that prospered until the generalization of antibiotics in 1940. It was these that effectively ended the massacre, and not the care administered in specialist institutions.

Chutes for corpses

The sanatorium and its illusions were for Colomina at the origin of the modernist imagination, the cardinal source of its great principles. Also she describes with care, in the manner of Michel Foucault, the misguided medical practices of these establishments, which at the time represented a veritable industry for a country like Switzerland: the practice of selecting the most robust patients in order to embellish recovery statistics and, above all, the treatment reserved for those whose health worsened during their stay, shut away in isolated parts of the institution and breathing most often the air of cellars. As for the bodies of the deceased, they never appeared. Hidden ramps and concealed entrances made it possible to evacuate them without disturbing the convalescent clientele. In Davos there were even chutes for corpses to hurtle down the slopes of the mountains.

The correlation between modernization and sanitation would continue into the first half of the 20th century, placing clean air as a major goal of architectural design and urban planning. It was also in this context that reducing the exposure of inhabitants to industrial pollution became an imperative.

What happens between medicine and architecture is similar to the relations that have often been observed between military industry and civil society. As soon as the war is over, military innovations are quickly turned over to civil society. In a similar way, the culture of the modern building would adopt considerations and practices developed in hospitals. If Colomina gives a long exposition of the principle of communicating vessels spreading the characteristics proper to the sanatoria, it is because she considers these phenomena of transmission a mechanism that can be applied to other cases.

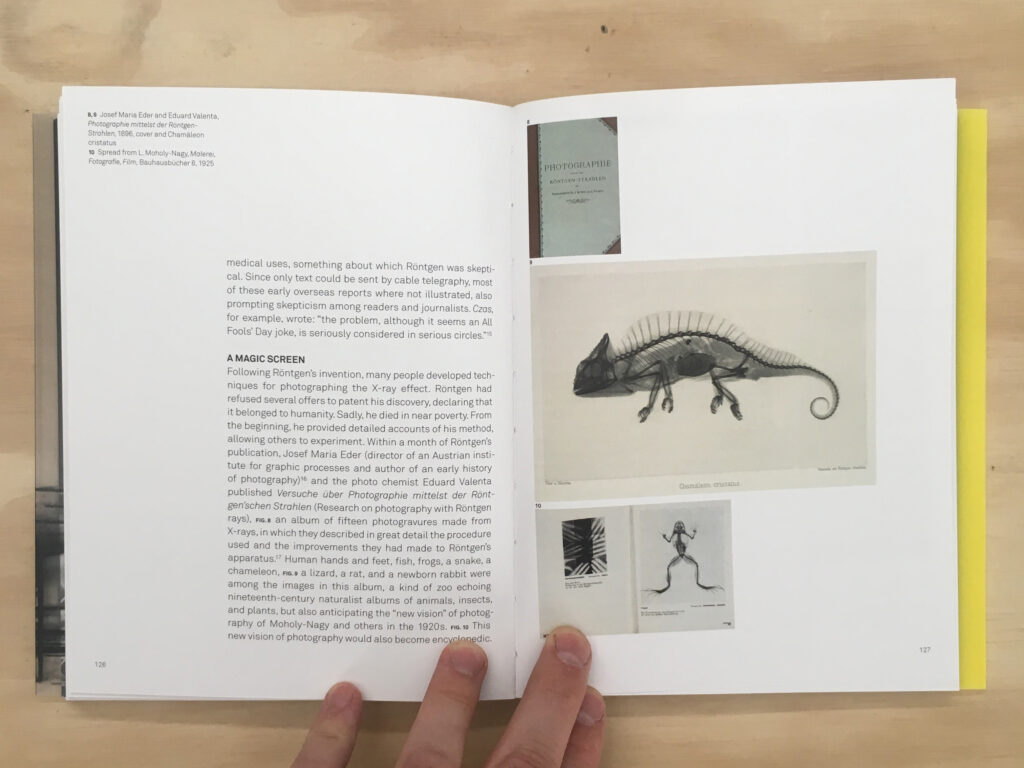

X-Ray Architecture, by Beatriz Colomina, spread

X-Ray Architecture, by Beatriz Colomina, spread

X-Ray Architecture, by Beatriz Colomina, spread

The illusion of transparency

The invention of X-rays widely used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis accompanied the development of an imagination of transparency, conceived as an emblem of progress. Humankind leaves the cave once and for all by reaching a crystalline stage made of reflections and translucent walls. Here again, it is a question of exposing the phantasmal substratum of an architectural practice. From what imagination, what fantasy universe, does glass architecture draw its representations? By linking the discovery of X-rays and the use of glass in architecture, Colomina manages to requalify modern transparency, showing that it is basically haunted by death. As in the case of the obsession with hygiene, it is a question of revealing, through the impact of a new medical technology, an alteration in the perception of what is public and what is private. The first X-rays were perceived as true intrusions into the intimacy of the body. One showed one’s X-ray to one’s lover as we now send a daring selfie. This disposition of a medical technology can in turn be transposed into architecture. It exposes the negative dimension of modern clarity. Here Colomina is pursuing a long-term effort to deconstruct, in the Derrida sense of the term, the daylight fundamentals of architectural modernity. Transparency would thus ultimately have more to do with the world of reflections, ghostly glimmers and illusions than with clarity and optical omniscience.

The last part of this critical X-ray finally invites us to question contemporary medical innovations and their influence on today’s architecture. Because this renegotiation between privacy and the public sphere continues and shifts perpetually. What conception of living spaces will emerge from nanomedicine or the medical imaging of the third millennium? Where and how will we protect ourselves from new physical and mental pathologies? The author prefers to lay out the terms of the problem rather than hurry to answer them.

X-Ray Architecture is, by its conclusion, in the continuity of the reflection initiated in 2017 at the Istanbul Design Biennial, of which Beatriz Colomina was the curator, with Marc Wigley. Questions of the negativity of design, its morbid part were explicitly posed there. Thus, Colomina is now pursuing this research which consists in exposing the collective unconscious, which determines not only our conception of domesticity but more generally of the modern form. Perhaps this is the actual invitation of this book: to analyze the main aesthetic choices that condition the things we use and the places we occupy.

This review was first published in: Artpress #464, March 2019.