Little Plans

On February 28, the Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) ended its three-month run. The venue – an array of concrete boxes and silos that was formerly the Dacheng Flour Factory, renovated by Doreen Heng Liu and her office NODE – will be demolished as part of the transformation of the Shekou waterfront district from factories and warehouses into a cosmopolitan cultural destination. Wasteful, perhaps, but indicative of the incredible energy being exerted on developing the city, and the money available to do so.

The UABB is a relatively new event, first held in 2005, making this its sixth iteration and tenth anniversary. In the meantime, new architecture biennales (or biennials) continue to appear around the world, each justified by its host city having some claim to a unique or extreme architectural environment. Taking inspiration from the original in Venice (an early laboratory for Occidental-Oriental hybridization and globalization), similar events now occur in cities that include Rotterdam (a paradigm of postwar tabula rasa Modernist planning), Chicago (an incubator for radical experiments in high-rise construction), Tallinn (a tiny, well-preserved medieval city), with Shenzhen providing an instructive demonstration of the effects of high-speed urban growth.

Predicated on Shenzhen’s well-known origin myth of a cluster of fishing villages that exploded into a metropolis in mere decades, the founders assert that UABB is “the one and only biennale of urbanism\architecture in the world”. Shenzhen is the product of an experiment in economic liberalization, the first of China’s Special Economic Zones, and an extreme case study in the ongoing urbanization of China. The rural population is surging into new cities being built to meet the anticipated demand for enormous quantities of housing and offices, with all their ancillary commercial, industrial, and recreational facilities. The urban legend, so to speak, of China’s ‘ghost cities’ – huge government developments that purportedly lack people willing to live in them – has turned out to be mostly exaggerated, or at least premature. The new cities indeed have a growing number of new citizens. But whatever the real balance between grassroots aspirations and top-down policies, the sheer quantity of this new construction has inspired the biennale’s founding statement by Aaron Betsky (one of four main curators, along with Doreen Heng Liu and Urban Thinktank’s Alberto Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner): “This biennale makes a simple argument: We have enough stuff. We have enough buildings, enough objects, and enough images. We certainly have enough cities and built-up areas.”

As a warning against the thoughtless destruction of still-useable building stock and the rejection of traditional living patterns that might retain some viability in the present day, the point is well taken. And no one in their right mind would argue against the profound importance of sustainable development and resource recycling. The message and method is not entirely new – for the previous UABB in 2013, the former YAOPI Float Glass Factory was transformed into an exhibition venue, which curator Ole Bouman titled the ‘Value Factory’ as part of a curatorial mission to pay attention to what exists before making anything more. Betsky’s take is implicit in everything from the biennale title, ‘Re-Living the City’, to its promotional materials – the catalogs, pamphlets, tote bags, notebooks, pencils, and so on are made from recycled materials, with traces of old newsprint and plastic packaging still visible.

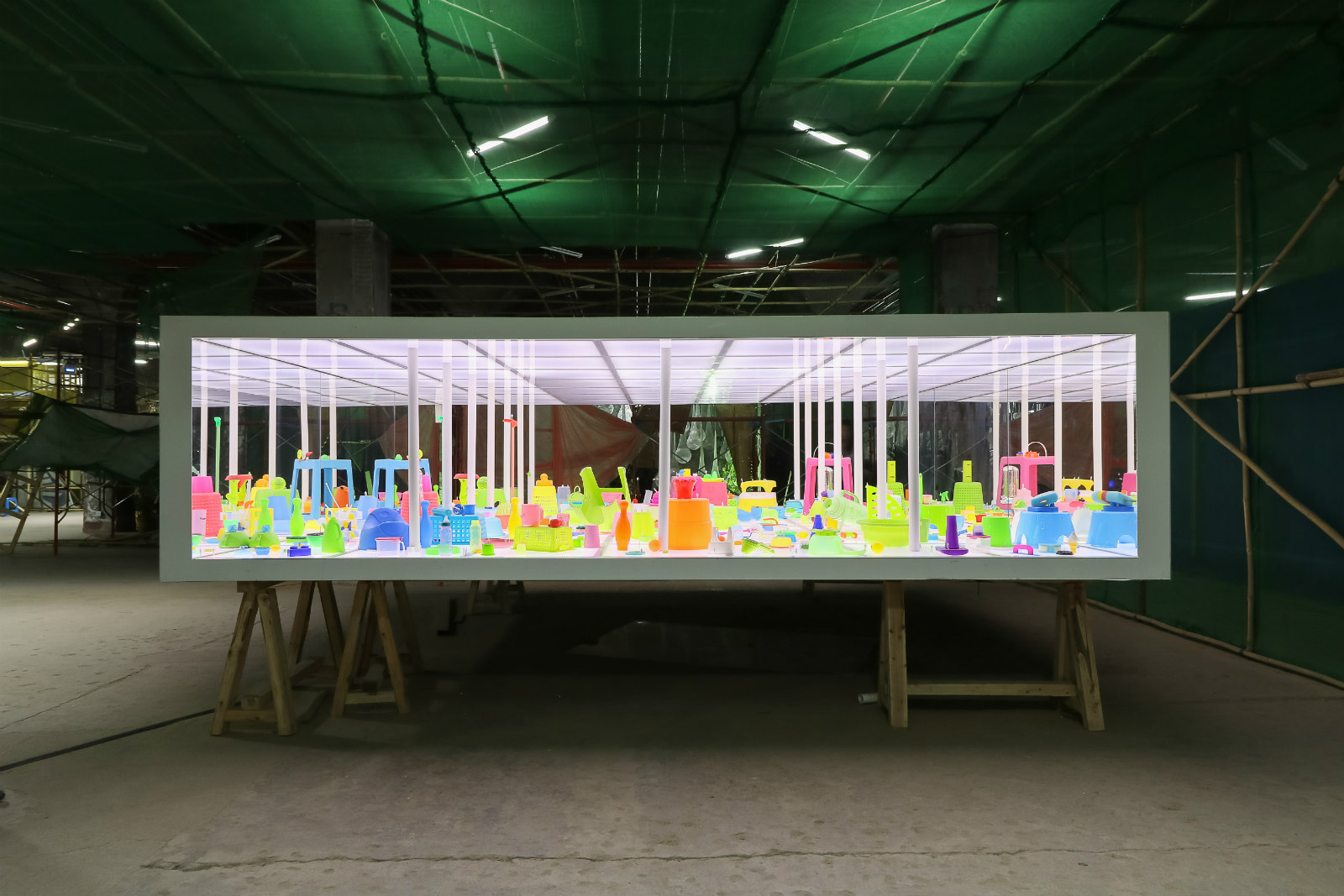

The curators each claimed a part of the venue to make independent but complementary exhibitions. Betsky’s section was titled ‘Collage City 3D’, explicitly referencing Colin Rowe’s 1978 book Collage City. But instead of Rowe’s observations of the accumulation of urban textures over time, Betsky asked exhibitors to search for discarded objects in the city to use in their installations. Many ended up with some variety of junk sculpture, such as ‘Shenzhen Entropy’ by Rob Voerman, and ‘Hole in the (Window of the) World House’ by Dennis Maher. Others encouraged participation, such as ‘The Ecstasies of Influences’ (its title taken from a Jonathan Lethem essay defending copy-paste plagiarism) by Lukas Feireiss and Thomas Tsang, a set of backboard cabinets with chalk provided for visitors to write graffiti. Jimenez Lai’s ‘Lost & Found’ was a collection of luridly colored plastic objects made in China, purchased in Los Angeles, brought over to Shenzhen, and then arrayed between two gridded lightboxes that deliberately recalled Archizoom’s dioramas for No-Stop City from 1969 – a sharp comment on the globalization and recycling of both objects and ideas.

Titled ‘Radical Urbanism’, Urban-Think Tank’s section was predicated on themes of political and environmental activism that also drew inspiration from the visionary projects of the 1960s. The emphasis was on description, not prescription, ranging from a catalog of sustainable systems titled ‘Autonomy & Autodigestion’ by ANAcycle thinktank (Lydia Kallipoliti with Meg Studer and Kyong Kim), to a study of ‘temporary’ architecture in refugee camps in ‘The National Pavilion of the Western Sahara’ by Manuel Herz, retroactive analysis of the effects of urban conflict in ‘The Urban-Data Complex’ by Forensic Architecture, and a condensed chronology of spaces for public protest in ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ by Crimson Architectural Historians.

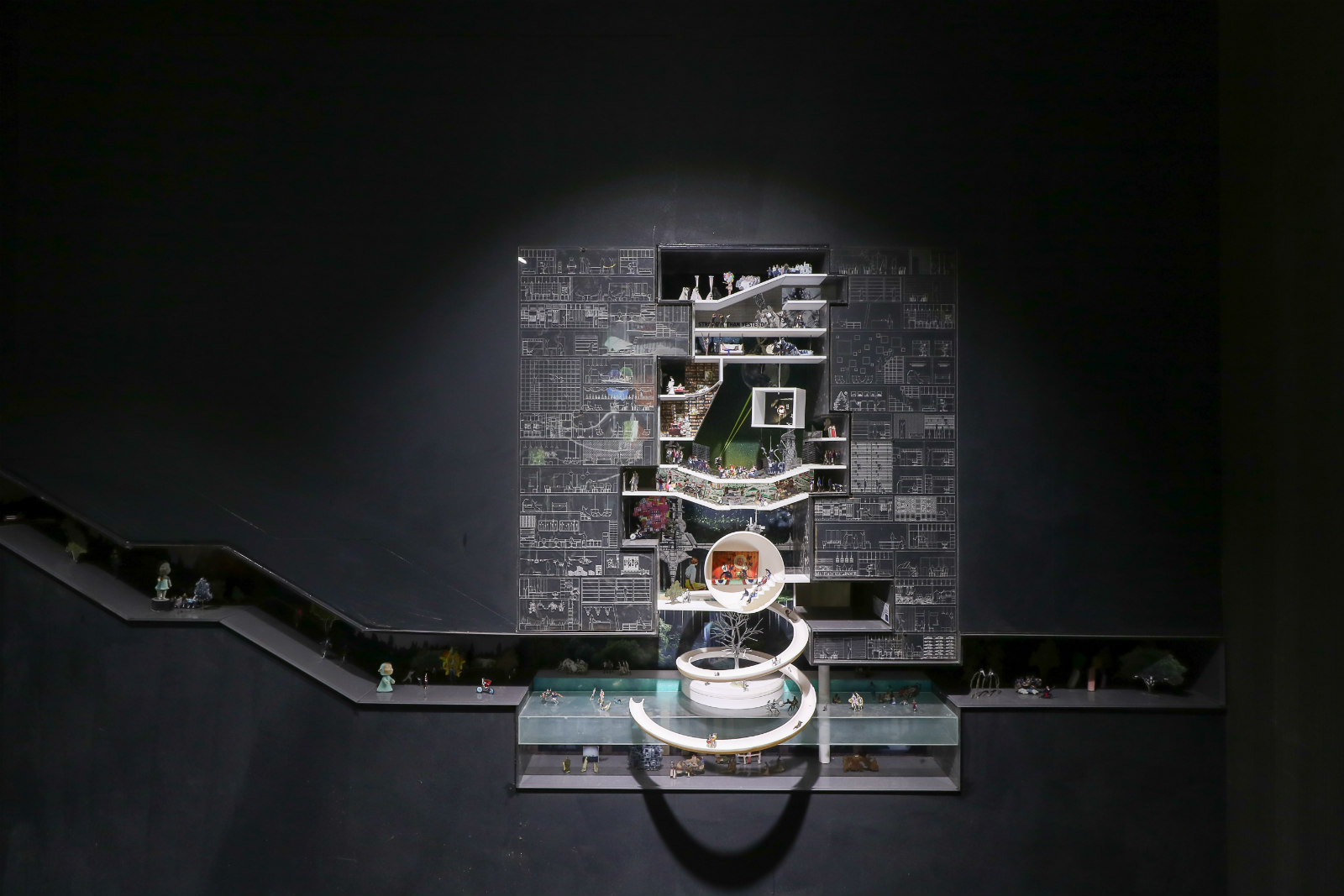

Containing some of the biennale’s more conventionally architectural projects, Liu’s section was called ‘PRD2.0’, a title that suggests it is an upgraded version of the old Pearl River Delta. Juan Du’s ‘From Villages to City: The Informal History of Shenzhen’ looked at the ‘urban village’ phenomenon, in which traces of Shenzhen’s recent past survive amid the modern city. Compared with the small-scale humility of most of the other contributions, ‘Megablock Urbanisms PRD’ by the Asia Megacities Lab at Columbia University’s GSAPP and ‘Hyper Metropolis’ by URBANUS presented the kind of large-scale interventions that are probably the most realistic response to circumstances in Shenzhen today.

Asked about the identity of her exhibition’s predecessor, presumably titled PRD1.0, Liu was momentarily caught off-guard, but then suggested it might be Rem Koolhaas’s mid-90s study of the Pearl River Delta. Undertaken with students from the Harvard GSD and collected in the book Great Leap Forward, it was indeed this research that first made the global architecture community aware of the extraordinary developments in the Pearl River Delta region. During his first public presentation on the topic (at a 1996 symposium held in Tokyo, called ‘Asia is Redefining the City’) Koolhaas lamented the retrogressive tendency of architects and urbanists to focus on minor or traditional aspects of urban life even as Chinese cities underwent transformations at a speed and scale unprecedented in human history:

“I expected the discussions to be about the incredibly fast development and the intense mutations in the Asian city. But they were paradoxically a whole series of extremely detailed ‘low-level’ issues concerning how the quality of living could be improved. Where I expected the architects to talk about what was happening on the skyline, the discussion was mostly about the pavement – as if the quality of the pavement dictated the quality of life. From that moment I extracted a potential law of Asian architecture and a law of architecture in general: the more convulsive or dramatic the developments are, the more detailed and evasive the preoccupations and discussions will be.”

A century ago, Chicago architect and planner Daniel Burnham famously entreated architects to “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.” In contemporary China, this doesn’t need to be said or encouraged. The incessant development may be both exhilarating and unnerving, but this biennale rightly celebrated delicate interventions and observations, the valorization and preservation of small moments of eccentricity, and the recycling of spaces and objects, as a necessary corrective to the headlong growth of this city – and, indeed, of any city.