Grindr Archiurbanism

For more than a decade Andrés Jaque has been researching the intertwined relationship between digital communication technologies and the urban: Grind Archiurbanism explores how, since 2008, gay dating app Grindr has created a new kind of hybrid place – a “zone” – where LGBTQ realities are both constructed and threatened. The text resonates with some of the works exhibited in Another Breach in the Wall (such as Queering the Map, the Uncensored Library, and Liberate Hong Kong) that expand the notion of “reality” beyond the outdated dichotomy online/offline.

“I was gay-born online”

Joel Simkhai was born in Tel Aviv in 1976 and soon migrated with his family to the conservative New York suburb of Mamaroneck. As a teenager in the 1990s, he started participating in what was the then-emerging world of online chat services, which he would use to meet guys. In the dark of his bedroom, with his parents watching TV in the next room, he would access the CompuServe CB multiuser chat channel 33 and AOL’s instant messenger service to connect to a multitude of gay guys. “I was gay-born online,” Simkhai said. “It was great, but most of the time I would end up talking to guys in places like Wyoming, Minnesota, or Washington, D.C. It was impractical.” 1

When he was 21, and still closeted, he lived for a year in Paris as a New York University exchange student. Disappointed by the limited options he found at the gay bars in Tel Aviv, where he spent his summers, he was amazed at the effect that a pioneering communications system called Minitel was having on Paris, whose population density was then 21,000 inhabitants per square kilometer, 27 times the density of Mamaroneck. With nine million users, Minitel, the French precursor to the internet, had already produced a digital language for online dating.2 It consisted of a videotext system that provided interactive content displayed on a video monitor. Even though it required its users to engage with an unwieldy device that had to be wired to a fixed phone line and placed in the user’s room, the high number of Minitel users made it possible to extend their text-screen conversations to offline encounters and sexual intercourse.

When spending his summers in Tel Aviv, Simkhai got to know WAZE, the location-based social media app developed to enable drivers to avoid congestion on the Israeli road system. What WAZE had done for gridlocked drivers, he believed he could do for lost gay men in search of sex.3

Over six months in 2008 – as Apple, Samsung, and Nokia were launching cell phones with GPS – Simkhai, Morten Bek Ditlevsen, and Scott Lewallen developed the first version of a location-based application that they called Grindr, a reference to the way grinding brings different coffee beans together, and also a portmanteau of guy and finder. It was designed to help gay men find other gay men in close proximity. In June 2009, on the BBC Two show Top Gear, British actor Stephen Fry showed Jeremy Clarkson how easy Grindr made it to cruise nearby gay men. A week later, 40,000 men had downloaded the app.4 For sociologist and Grindr user Jaime Woo, “It was like gaining Superman’s X-ray vision, and suddenly being able to peer through brick and steel to reveal all the hungry men around. People use the term ‘gaydar’ to refer to a queer man’s ability to sense another man as a fellow queer…Grindr felt like a literal radar.” 5 In its free version, Grindr opens with a display of 12 photographs of the closest individual users, with their names in the lower left corner. The profiles shown can be filtered by age, body metrics, ethnicity, preference in sexual position, relationship status, and also by the way users identify themselves – as one of 12 “Tribes”: Bear, Clean-Cut, Daddy, Discreet, Geek, Jock, Leather, Otter, Poz, Rugged, Trans, Twink. Scrolling down reveals up to 100 nearby users, often shirtless or naked.

Alkali-aluminosilicate as Networked Human Skin: From Places to Profiles

The texture of a smartphone’s alkali-aluminosilicate glass screen is similar to smooth skin, so as you rub your thumb down the display of Grindr users, it is like touching the young, hairless skin of a naked body. The display promotes interaction: blocking, favoriting, and messaging are the next steps. When a user’s picture is tapped, his profile expands to occupy the whole screen. A user’s profile consists of the guy’s proximity, age, body metrics, and intentions, a headline, and a 120-character “About Me” section. These are the features guys use to construct themselves on Grindr (or that Grindr uses to construct them online).

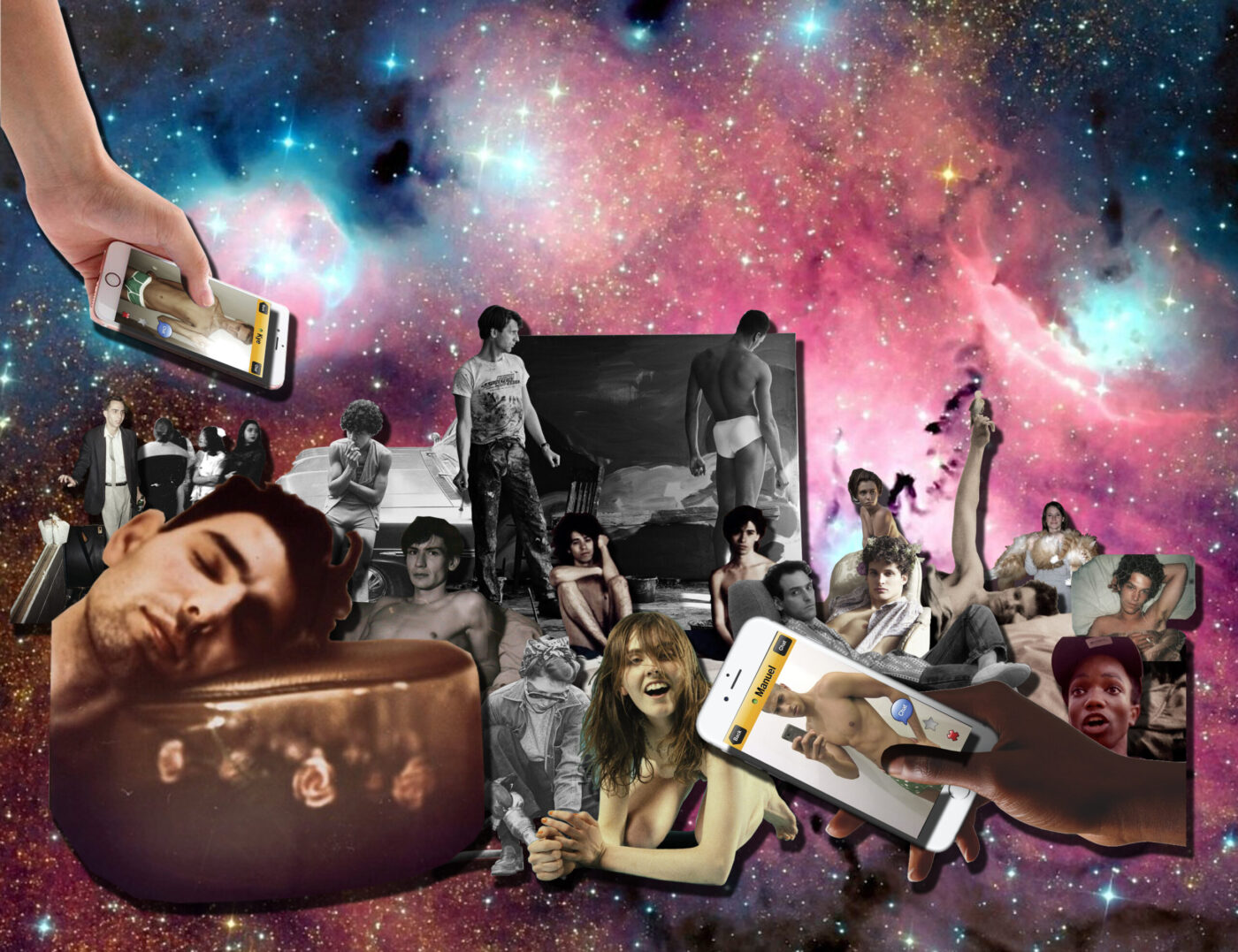

As one user put it: “Nothing matters on Grindr besides the picture.” 6 Photographs mainly show sexualized versions of users, often in desirable interiors, with carefully selected outfits. Less than five percent of the conversations happening on Grindr end up in offline encounters.7 Grindr provides a new mode of romantic experience, not one in pursuit of forever love, or even genital interaction, but rather a desire-driven dérive through profiled assemblages of porn, fashion, and interior design. The physical experience of the finger-scroll on the alkali-aluminosilicate surface – a tiny gesture repeated all over the world for an average user time of 90 minutes a day – requires and triggers important architectural and urban transformations. Alkali-aluminosilicate is human skin, networked.

What’s up? What’re you up to? What u into? Where u at? Trying to meet people. Are u interested? What are you looking for? Visiting. Looking for someone to show me around. Have more pics? How old are you? Horny. Show me your dick. Are you a bottom? Wanna fuck? Grindr conversation tends to be simultaneously casual and intimate. But the app accelerates romantic serendipity by creating a space of visually driven pre-agreed normativity. It was designed to replace online chat rooms with an overlapped urban network that prioritizes proximity and renders gayness interconnected and accessible. The 3.0.9 version of the app, released in October 2016, removed the orange frame in its interface to avoid publicly exposing Grindr users with the orange glare of their smartphone screens on their faces when, for instance, they check the app in the dentist’s waiting room, or even in the middle of a meeting. Grindr is an online archiurbanism that enables offline spatial layering; creating a multiplying type of space where simultaneous techno-human settings can be promoted.

Grindr is a zone of its own. It is not a city. Whereas cities are often seen as places for social convergence, Grindr is a device that sorts out the social, an infrastructure rendering its users as selected members of a specialized community within society. It is enacted more than constructed. It is neither fully virtual nor physical. It is an archiurbanism that – evolving from the long-running traditions of queer urban lacunas where normativity was challenged and cruising strangers became possible – has reinvented the offline domain. Predictions about the way digital communication would make proximity irrelevant have been proven false. Proximity today is still important; it is multiple, selective, and technologically manageable. With 10 million users in 192 countries, and growing at a rate of 10,000 downloads per day, Grindr processes a flow of more than 70 million messages a day. People inhabit it not only in the dark of bedrooms but in offices, bars, streets, trains, factories, gyms, and college campuses. Author and user Jeff Ferzoco said that he needs Grindr to get a sense of who is in the room.8 Grindr provides transparency, but not the universal transparency of modernist glass; it provides selective transparency among those participating in an exclusive layer of a fragmented transnational urbanism, made in the intersection of bytes and flesh, that comprises five trillion bytes of data in use, stored in servers located in 23 sites in only two countries: the US and China.9 Grindr pioneered what became a diverse market of proximity-based social media apps, including Badoo, Blender, Blued, Down, Glimpse, Happn, Hinge, Jack’d, JSWipe, Nuh Lang Nah Lang, Pure, Tinder, and Scruff among many others.10 These apps have not only radically changed the way we understand and experience sex, but has also reinvented urbanity by enrolling more than 360 million people around the world in a customizable infrastructure where digital self-construction replaces the need for physical buildings and intimacy between strangers.

The Western De-queering of Gayness: Sex and Real Estate

If places (bars, clubs, saunas, cruising spots) used to be what produced LGBTQ scenes, it is now the self-construction of subjects – through online editing and circulation – that defines gayness. Cruising spots and dark rooms around the world have seen their aging constituencies reduced in recent years, as younger generations have abandoned them for digital spaces to cruise and negotiate sex. In London, historic gay venues like The Black Cap and Joiners Arms awoke people’s, officials’, and the media’s concern when they were demolished to make way for apartments. Similarly, in New York, venues such as the Latino gay club Escuelita and the West Village’s Westway club were replaced by apartment towers and condominiums.11 According to the New York City Department of Buildings, 15 new building permits for apartment towers in Hells Kitchen and the Garment District were approved in 2015. The combination of a shift in the way air rights regulations are interpreted – enabling the concentration of constructed volume within blocks – the possibility for limited liability companies to hide the identity of real estate owners,12 and the now-expired 421a tax exemption program,13 has prompted the development of high-end apartment towers around the city. This phenomenon followed Michael Bloomberg’s post-2008 initiative to get “every billionaire around the world to move [to New York]” by offering safe real-estate products where investments could be allocated.14 In 2016, apartment towers in Chelsea, East Harlem, and Greenpoint were Grindr users’ favorite locations to find lovers worldwide, and Saturday at noon, not night, was their preferred time of the week.15 Whereas the erotic industry used to occupy economically depressed parts of a city, now areas like rent-spiking Greenpoint and Chelsea have become the places for popular adult studios like Burning Angel or Cocky Boys to use postindustrial lofts and apartments with floor-to-ceiling windows as sets for their shoots. Due to the growing normalization of LGBTQ lifestyles in Western countries, historical sites of queer empowerment have lost their role of accommodating the marginal and have become spaces of aspirational real-estate investment. If the queer movement historically challenged heterosexual couples as the respectable form of sexual allocation and claimed nightlife and trash16 as spaces for social justice, then the one-to-one relationship that Grindr’s interface prioritizes, and the progressive replacement of gritty venues with bright apartments in former gayborhoods, marks an evolution in which gayness is less a victim and more an actor in the making of normative culture.

Self-Designing as Shelter: Social Media

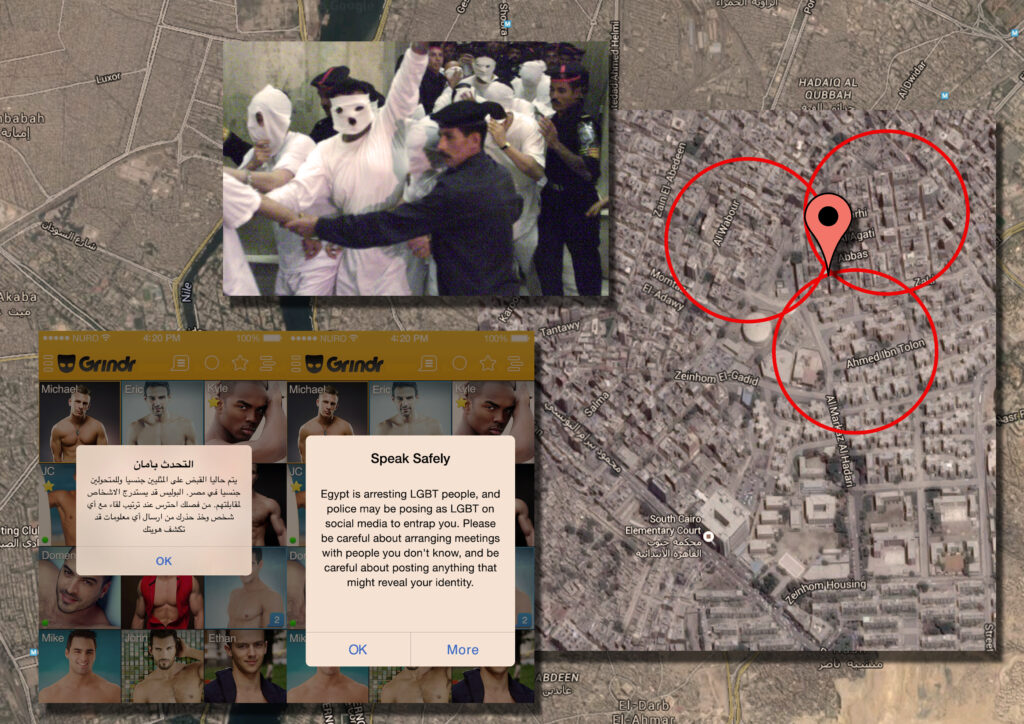

Seventy-three countries and four independent political entities have criminal laws against LGBT activity, making social media a place where LGBTQ realities are both threatened and constructed. “One, two, three, four; open up the closet door” is how GHAR, the pan-Indian Gay Housing Assistance Resource, presents itself on Facebook. Since 1998, GHAR has been helping queer people find shared apartments throughout India, where people continue to be arrested on accusations of homosexuality.17 GHAR user Sachin Jain says, “On Facebook one can seek reassurance by taking a glimpse of a person’s profile.” 18 For people like Sachin, social media is a source of assurance, but in Saudi Arabia, where a pharmacist spent two years in a crowded Jeddah prison cell with other men convicted of homosexual acts, using social media can be a risk. “The religious police know all the apps and chat rooms,” he said. Some of his cellmates “had got a phone call asking to meet, from someone they’d talked to before on WhatsApp, and that guy turned out to be police.” 19 In 2014, Egyptian police were reportedly using Grindr to track gay and lesbian people in Cairo as well.20 Since Grindr presents profiles with the closest user’s profile first, it is possible to triangulate the location of any user by using three coordinated smartphones that have Grindr accounts. In October 2013, 14 men were arrested and charged with practicing homosexual acts in a small, traditional hamman in the El-Marg district of northeastern Cairo. Egyptian LGBTQ activist websites warned readers of the threat. A spokesperson for the popular Gay Egypt website stated, “Even if you live in a densely populated area, you only have maybe 500 houses within a 100 metre radius… If you live in a smaller area – the risk is even higher… It is a very dangerous situation, just be careful – we are already being monitored.”21 In a country where most print and broadcast media are aligned with homophobic laws, Grindr used its advanced online access to warn LGBTQ people in Egypt: “Egypt is arresting LGBT people, and police may be posing as LGBT on social media to entrap you.” In 2001, four men detained at a party in East Cairo’s Nasr City surprised the media by wearing white fabric masks – similar to the Grindr logo that would appear eight years later –when being transported to court. According to Scott Long, founding director of Human Rights Watch’s LGBT Rights program, “They wore the masks in both self-defense and defiance: to prevent the photographers who mobbed each hearing from spreading their pictures on front pages, and to protest the Egyptian government’s determination to milk a public relations coup from their humiliation.”22

In the Grindr display, users emerge through carefully curated portraits. Many show themselves as shaved tanned torsos, others as nice T-shirt-wearing ultra-normal guys. Self-editing and participation in others’ self-editing is what you do to be part of the app’s society. According to Grindr, its mask logo shows how our social life is based upon constructed external versions of ourselves. Politics on Grindr, and between Grindr and the realities it overlaps, are enacted in the ways self-presence is described, tracked, pictured, edited, and circulated.

Grindr is also an actor in the making of other forms of politics: the politics of those in transit. Omar Abdulghani, a law student from Al-Zabadani, Syria, flew to Istanbul in May 2015. Grindr was blocked in Turkey, so he used WhatsApp to find places to couch surf and to get in touch with the smugglers who facilitated his way onto a crowded rubber boat to Greece. “It felt like a horror movie. When we arrived at the beach, [we] started kissing the ground. I was crying… Most of the other phones were dead because of the water. But my phone worked, because I had wrapped it with plastic all over.”23 Four months later, he arrived at the Asielzoekerscentrum in the Dutch village of Ter Apel. When he turned on Grindr, Omar found someone just 20 meters away. “I was happy,” he said, “but also scared that they could find out in the camp. It was like being back in Syria… Having a piercing was enough for people to look down on me.”24 A few days later, in the Zaandam camp, Omar found two other gay guys on Grindr. “But they were closeted and would only chat online but would never talk to me in person,” he said. In the camp, people threatened to kill me. They told me I was the shame of the refugees, and they pushed me in the queue to get coffee.”25 On a Facebook group dedicated to helping refugees find rooms, Omar met Lianda, a 25-year-old lesbian woman who offered him a room. Via Grindr, Omar met Patrick, a Dutch guy with whom he is now in a relationship.26

In September 2015, the Greek electrical engineer Elias Papadopoulos used 5,000 euros he had saved to build a self-sustaining Wi-Fi hub inside a trailer at the Idomeni refugee camp. Many of the 13,000 refugees then living there had smartphones but not the money for overpriced SIM cards, so they seldom used their phones.27 A refugee named Fareed arrived at Idomeni after a long journey that had started in Kabul in October 2015. Along the way, 15 Grindr users helped him avoid police and find the camp. Whereas most refugees would trust the information provided by fellow refugees or distant friends, using Grindr, Omar could find nearby strangers willing to help with updated local information. He only met two of them offline. In Idomeni, using the Wi-Fi Papadopoulos had built, Fareed learned from fellow Grindr users about Tom, an LGBTQ activist who would provide two nights of shelter and information for LGBTQ refugees. In Belgrade, using Grindr, Fareed met Osama, another Syrian refugee, and together they moved to the squat shelter of Miksaliste in June 2016, where they lived for a year as asylum seekers.28 In these stories resound Didier Eribon’s explanation of the gay and/or queer self as a collective context born in response to insult, rejection, and the exclusionary social order these forms of violence establish. Refugees’ unauthorized crossing of borders is again a collective context shaped by insult and rejection. On Grindr, LGBTQ refugees like Omar or Fareed found a responsive society of strangers, available in proximity and connected by otherness; but still an urbanism based on differences, in which legally recognized citizens engage with disenfranchised victims of transnational friction and inequality.

Fashion, Porn, and Interior Design: Social Media Is Where People Are Now

In 2016, to celebrate Grindr’s seventh anniversary, the company released a short film starring artist and gay porn actor Colby Keller performing William Shakespeare’s monologue, “The Seven Ages of Man.” The film finished with the figure of a gold-crowned Keller ascending into the air, a poetic representation of rebirth. In May 2015, Grindr had initiated a 10-month/10-step integral reconstruction, orchestrated to turn the app into an expanding milieu for an immersive lifestyle experience.

Step one: Grindr hired Raine Group LLC to find a buyer so the company could raise capital for development. Eight months later, in early January 2016, Grindr sold 60 percent of its stake to the Chinese gaming company Beijing Kunlun Tech.29

Step two: Lukas Sliwka, Grindr’s chief technology officer, launched a new Grindr software stack. Initially, Grindr’s digital infrastructure was composed of customized solutions, which compromised their in-house engineers’ time since only they could do updates. The new stack used off-the-shelf components, which meant updates could be easily outsourced, and Grindr’s engineers could concentrate on expanding the app and finding new ways to cater to its users.30 Whereas Uber, which has an estimated eight million active users, was valued at more than 25 billion dollars, Grindr, with 10 million users, was valued at 155 million when BK acquired its majority share.31 According to the programmers forum “Venture Beat,” Grindr is continuing to expand by introducing value-adding services, transforming itself into a broader gay lifestyle platform by building alliances with high-profile members of high-end entertainment, fashion, and design industries.32 For Simkhai, “It’s not about the money. It’s about what gay men want in their lives.”

Step three: In September 2015, Landis Smither, former Playboy creative director, was appointed Grindr’s vice president of marketing. Smither says, “A third of the time on the app, people aren’t looking to hook up; they’re looking to kill time… I was looking at my Tumblr feed and I realized that it’s basically fashion, fashion, porn, porn, interior design, art, porn, porn. It’s just how we absorb things these days. And I would like to have a tool where I can do that in real life.”33

During London Fashion Week in January 2016, Grindr gave its users a code to access an exclusive live-stream of J.W. Anderson’s Autumn/Winter 2016 menswear show. In April 2016, Paper magazine announced that the male models for its summer issue would be cast from Grindr, making fashion magazines an extension of Grindr’s transmedia urbanism. Lots and lots of potential young, fit, healthy, sort of fluent models were right there, just a few feet away from users’ smartphones. Diesel’s creative director, Nicola Formichetti, said of the decision to advertise on Grindr, “Social media is where people are now. We live on our phones. I want to go where people are. Tinder, Grindr, and Pornhub might appear a little left-field. But it’s Diesel. We are not scared of these places. We are street.”34 Gay urbanisms, once providing havens for queerness and alternatives to market reductionism, are on their way to becoming mainstream marketplaces. The general acceptance of gayness in European and American urban scenes was often attached to the establishment of a normativity based on youth culture, fitness, fashionability, and health.

Cities do not accommodate Grindr. Grindr became the city. It is also itself a form of architecture, one based on the collaboration between heterogeneous technologies operating at different scales. One that has redefined what being in a room means, the notions of proximity we live by, what density is about. One that requires aesthetics, interfaces, and memberships to be sensed. One so successfully integrated in daily life that it is rarely noticed. Grindr is an archiurbanism. Operating globally from two world locations, Grindr is shaped by a simple code that diversifies locally in a myriad of ways for gayness to be collectively instituted. It becomes a milieu for gay men to constitute themselves as a collective of strangers, as a response to LGBTQ marginalization, overlapped with other forms of techno-human networking. It has also become an interface where entitled citizens and disenfranchised people may interact and where people, both settled and in transit, can find opportunities to connect and collaborate. In many Western cities, Grindr is in part both the cause and effect of the displacement of queer urban space by condominium towers.

Andrés Jaque is an architect and scholar, and founder of the Office for Political Innovation. This article was originally published in issue #41 of Log – Working Queer, Anyone Corporation, in 2017.

The Writings on the Wall is an editorial project developed in collaboration by Volume and Beta – Timișoara Architecture Biennial, about the capacity of loopholes to create exceptional experiences among the laws that produce our urban spaces.

Polly Vernon, “Grindr: a new sexual revolution?,” The Guardian, July 3, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/jul/04/grindr-the-new-sexual-revolution.

Joel Simkhai, “An encounter with Joel Simkhai, founder of Grindr,” interview by Philip Utz, Numéro, August 25, 2016, http://www.numero.com/en/culture/culture-encounter-joel-simkhai-founder-grindr.

Joel Simkhai, CEO and founder of Grindr, in conversation with the author, July 2016.

Vernon, “Grindr: a new sexual revolution?”

Jaime Woo, Meet Grindr: How One App Changed the Way We Connect (Canada: Jaime Woo, 2013), 8.

Jake Nevins, “Growing Up Grindr: A Millennial Grapples With the Hookup App,” New York Magazine, June 17, 2016, http://nymag.com/betamale/2016/06/growing-up-grindr-a-millennial-grapples-with-the-hook-up-app.html.

Mike Lane, vice-president of product development, in conversation with the author, July 2016.

Jeff Ferzoco, The You-City: Technology, Experience & Life on the Ground (San Francisco: Outpost19, 2012).

Grindr Development Team in conversation with the author, July 2016.

Grindr was launched in March 2009. Tinder and Blued were launched in 2012.

Michael Musto, “Gay Dance Clubs on the Wane in the Age of Grindr,” New York Times, April 26, 2016.

Michael Musto, “Gay Dance Clubs on the Wane in the Age of Grindr,” New York Times, April 26, 2016.

See Evan Bindelglass, “Everything You Need to Know About NYC’s 421-a Tax Program, Poised to Expire Today,” Curbed New York, January 15, 2016; and Kriston Capps, “Why Billionaires Don’t Pay Property Taxes in New York,” CityLab, May 11, 2015.

Michael Bloomberg’s statement in the New York Times: “If we could get every billionaire around the world to move here it would be a godsend; that would create a much bigger income gap.” Quoted in Sam Roberts, “Data Supports Bloomberg on Disparity with Income,” New York Times, September 27, 2013.

Grindr, Data Analysis Department, in conversation with the author, July 2016.

The term trash refers here to the counterculture that emerged in the 1980s in cities like New York, Berlin, and London and developed new forms of reappropriation.

Shemin Joy, “600 homosexuals arrested in 2014,” Deccan Herald, January 1, 2015.

Dheera Gurnani, “Gay queer parade: Walking out of the closet with pride,” DNA India, February 3, 2013.

Associated Press, “For some gays abroad, social networking poses risk,” Daily Mail, September 28, 2014.

Hakan Tanriverdi, “Jagd auf Schwule – via Dating-App,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, September 11, 2014.

Quoted in Conor Sheils, “Egyptian Cops using Grindr to Hunt Gays,” Cairo Scene, August 31, 2014, http://m.cairoscene.com/LifeStyle/Egyptian-Cops-Using-Grindr-To-Hunt-Gays.

Scott Long, “The Trials of Culture: Sex and Security in Egypt,” Middle East Report 230 (Spring 2004), http://www.merip.org/mer/mer230/trials-culture.

Circe de Bruin, Lucia Hoenselaars, and Machiel Spruijt, “My Phone Helped Me With Everything,” Public History Amsterdam (blog), December 2, 2015, http://publichistory.humanities.uva.nl/queercollection/my-phone-helped-me-with-everything/.

Harriët Salm, “Homopesten leidt tot vlucht uit azc,” trans. Michael Nathan, Trouw, January 25, 2016.

Maroles de Moor, “Homoseksuele Omar werd bedreigd in azc’s, Lianda nam hem in huis,” trans. Michael Nathan, Het Parool, February 15, 2016.

Omar Abdulghani and Paola Pardo in Skype conversation with the author, October 2016.

Julius Motal, “This man provided free Wi-Fi to refugees stranded in Greece,” Mashable, March 18, 2016, http://mashable.com/2016/03/18/meet-the-man/#k56C_dvexZqq.

Fareed and Osama requested the author not to publish their last names. Fareed was first found and contacted by the author and Paola Pardo with the help of the NGO Zaatar. The story included here was reconstructed by the author with the assistance of Paola Pardo through the documents Fareed published on Facebook and a series of Skype conversations in September and October 2016.

Mike Isaac, “Grindr Sells Stake to Chinese Company,” New York Times, January 12, 2016.

Grindr Development Team in conversa-tion with the author, Spring 2016.

Mike Isaak, “Grindr Sells Stake to Chinese Company.”

Venture Beat Staff, “Mobile app analyt-ics: How Grindr monetizes 6 million active users,” Venture Beat, April 11, 2016, https://venturebeat.com/2016/04/05/mobile-app-analytics-how-grindr-monetizes-6-million-active-users-webinar/.

Emma Hope Allwood, “What’s Grindr’s new agenda?,” Dazed, June 2016, http://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/29181/1/grindr-s-new-agenda.

Steve Salter, “Why you’ll soon be seeing Diesel ads on Grindr, Tinder, Pornhub, and Youporn,” I-D, January 10, 2016, https://id.vice.com/en_au/article/evnkwp/why-youll-soon-be-seeing-diesel-ads-ongrindr-tinder-pornhub-and-youporn.