Archiprix International in Ahmedabad

Arjen Oosterman

From its inception at the dawn of the millennium (2001), Archiprix International has proved to be an adventure with enormous ambition. To collect, once every two years, the very best graduation projects from architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design schools around the world is no small feat. To comprehensively exhibit this material is also a challenge, and to create a meaningful and productive event around the award session—giving center stage to the selected graduates and their projects—is a task akin to walking a tightrope. And yet, this is what they are achieving.

There are a few, simple components to the formula that are key to its success. The first: stimulating new talent, a factor which stands undisputed as schools, the building industry (Hunter Douglas as sponsor), and graduating students themselves are happy to take part in. As a concept, it naturally relates to each stakeholder’s interests and goals. Secondly, the award is a clever mix of Hollywood formuli: the mixture of a professional jury and a popular vote. A jury selects a shortlist of nominees (23 in the case of this year) and selects the best eight. The shortlisted nominees are announced in advance, thereby building momentum and, during the grand award ceremony, the eight award-winning projects are presented. In addition to the professional jury, all participants are also asked to cast their vote resulting in a parallel selection of the “participant’s’ favorites.” Both of these categories (41 projects in total this time around, some favorites doubled with the jury nominees) are presented as a special section in the main exhibition. And, thirdly, the program is enriched by workshops preceding the award ceremony for which the participants can register. In reality around a fifth actually take part.

This formula is successful in providing exposure to young talent, forging network opportunities on a truly global scale, and to create what could be described as a benchmark moment for all participating (and even those non-participating) schools. The exhibition displays what the newest generation is up to and shows which schools are the most successful in delivering interesting practitioners. It even shows—when you take time to take it all in—trends and developments among the different ‘shifts’ leaving the schools.

This incarnation was held at CEPT University in Ahmedabad, India. Designed by Balkrishna V. Doshi, the campus is an incredible demonstration of how relaxed and generous architecture can be; how buildings can invite occupation instead of prescribing use. Ahmedabad as context is adding to this a collection of centuries-old and Modernist highlights, among them several Le Corbusier designs (Mill Owners’ Association Building, Villa Sarabhai, Sanskar Kendra Museum, Villa Shodan), a Louis Kahn (Indian Institute of Management), an Eames (National Institute of Design), and so on. But apart from “the masters”, this part of India seems to be the natural habitat for architectural Modernism – in fact, its spatial ambitions can be explored to the full in this climate, unhindered by the need to protect from the cold, to seal off buildings and cocoon them. The city is also full of particular challenges that come hand-in-hand with metropolitan development. All in all, therefore, fertile ground for the workshops to explore.

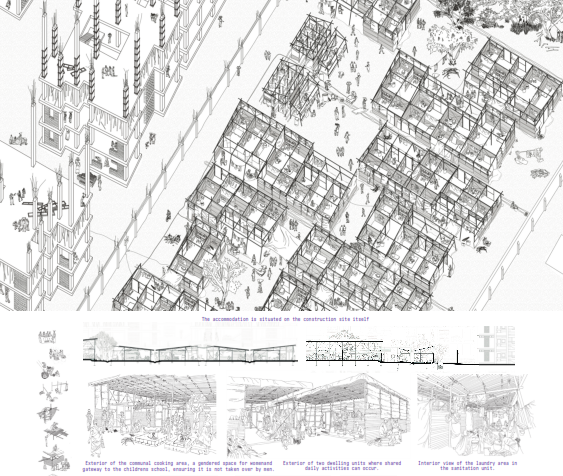

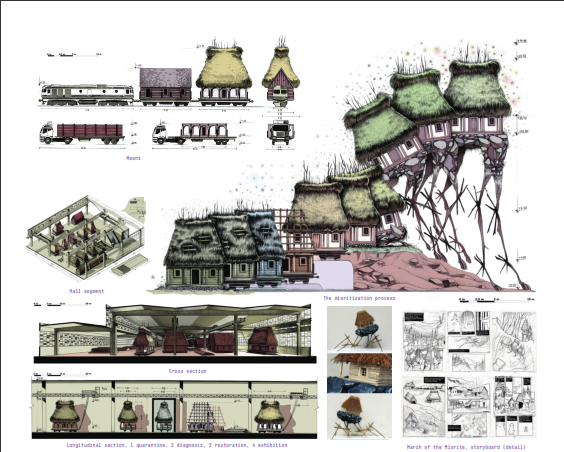

As far as the harvest is concerned, It was interesting to observe that a theme like sustainability is no longer the main focus of many projects, but a programmatic component that is more naturally interwoven with the core issue being confronted. Another striking new reality was that there were so few projects that were “dressed to impress” (like the majestic stadium, the power tower, and so on). The attention was rather dedicated to needs and situations that begged for attention; for clever solutions and inventive processes. There was clearly an eagerness among participants to contribute and make a difference – and, therefore, to not stand out so much.

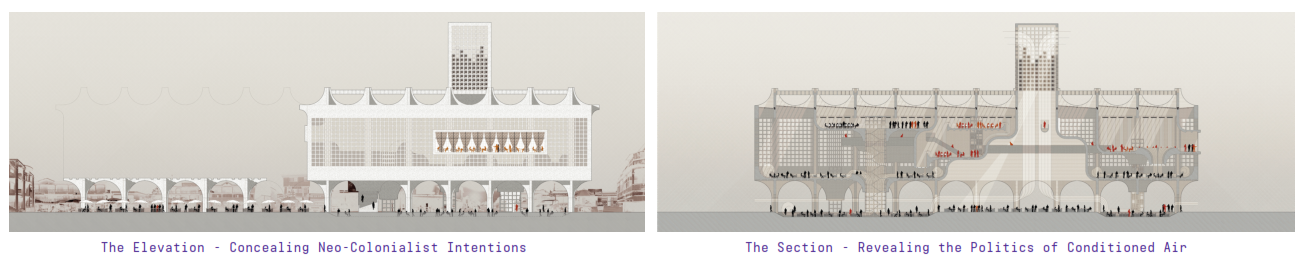

The Russian submissions demonstrated that hardcore Beaux-Arts methodology (dominant in most of their projects until this year) appears to be in retreat – and what a relief. Speaking more globally, an ever greater percentage of the participating projects reach a high level of sophistication (in presentation and in addressing the issue the project focuses on). Naivety can only be found in a few projects, in my opinion. It’s hard to say if this is part of the “Archiprix Effect,” stimulating schools to provide a better education, but international exposure and exchange are certainly influential – also in what students expect and demand from their school. There is also a clear (re)surfacing of an awareness of the political agency of architecture. Jason Tan’s (Singapore) project, dedicated to “the politics of conditioned air in a gold-rush boomtown”, is a good example. In his Gold Exchange annex Gold Miners Union building for Dunkwa, Ghana he cleverly exposes the exploitative presence of China in Africa.

And while this all sounds like good news, architecture and architectural practice have to change in order to play a (more) relevant role in the transformations and challenges our societies are being presented by. Exhibiting talent and stimulating quality education is important, but it may not be enough. How to properly connect the inside and the outside of the profession is the next hurdle.

Size-wise, Archiprix International may be reaching its limits. The catalogue includes the full list of all 1700 architecture/urbanism/landscape design schools in the world, a telephone book of sorts, also indicating which schools contributed to this Archiprix and which ones participated in previous ones. Some schools supported all nine events, some tried once and never returned. By ‘landing’ the event every time in a different country and continent, the Archiprix organization hopes to persuade ‘local’ schools to join in. With good result, because the total number is still growing. There is also a growing number of countries that sets up a national Archiprix, modeled on the Dutch original (that dates back to 1979). Great, keep up the good work. But a concern seems that some of the more prestigious schools, like the Ivy League schools in the US are (still) not participating. One can think of two reasons: for big schools it is simply too complex to select and submit one plan, or there is not this one person taking responsibility for the process (in the end it is always individuals that make a difference). Another could be the competition element: if, let’s say a graduate from Columbia doesn’t win an award, or worse, is not even nominated, the school has lost. Some schools don’t want to be exposed to such ‘criticism’. Participating includes risk taking.

A more fundamental challenge is that architecture is becoming more and more an interdisciplinary activity and process, in which the architect is one of the advisors. This ‘integral process’ development, resulting in collaboration between different proficiencies and disciplines is much harder to present in six panels and judge without reading extensive explanations. Schools will also select with the project’s potential for success in mind. And the Archiprix formula seems particularly suited to give brilliant designers extra exposure, magicians with space and material. Today, this may not be top priority when it comes to generating attention for and repositioning the relevance of the field of expertise called architecture.

The workshops are clearly an attempt to broaden the formula and to include some aspects that are much harder to get across in the competition itself. Like collaboration, like addressing local issues from (literally) different backgrounds, like the role of research. And yet, how to make this more than an important experience in the lives of some eighty young professionals is a challenge. Broadcasting in multimedia times is still a serious struggle.

There is also a challenge when it comes to making connections to the field of production. How do you reach, as Archiprix organization, decision makers, creators of policy plans, corporate clients and so on? Countries that started their own national Archiprix seem more successful in establishing such connections, making good use of the prestige that comes with Archiprix International. But it remains a hard reality.

It appears that the profession of the architect is being challenged from two sides. Part of the architect’s professional knowledge is and will further be absorbed by expert systems, in direct connection to the building industry and production. And part of the architect’s say and control over ‘the design’ is taken over by the consumer, being quite capable to indicate their own needs and preferences. That doesn’t leave the architect empty handed, but it does pose the question: how do you prepare the professional—formerly known as the architect (as Kas Oosterhuis puts it)—for the tasks and challenges at hand? How to provide a platform that stimulates talent able to perform under such conditions?

Ahmedabad: Cross Section (part 1) from ArchisVolume on Vimeo.

Ahmedabad: Cross Section (part 2) from ArchisVolume on Vimeo.

One of the more spectacular products of this year’s workshops was the preparatory document that was created on the initiative of the workshop organizers Jigna Desai and Íñigo Cornago: a 9.5 meter long leporello called ‘Ahmedabad: Cross Section’. It is a compilation of maps, charts, data, interviews and reflections giving insight in the city on many levels and illustrated with a ‘full length’ cross section of the city, beautifully drawn by Tanvi Jain and Chandani Patel. A unique information object.